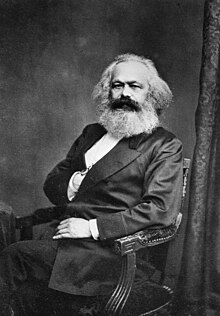

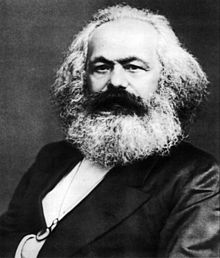

Karl Marx

German-born philosopher (1818–1883)

Karl Heinrich Marx (5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German political philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, journalist and revolutionary socialist. Marx's work in economics laid the basis for labor theory of value, and has influenced much of subsequent economic thought. He published many works during his lifetime, including The Communist Manifesto (1848) and the first volume of Das Kapital (1867), the two later volumes being completed by his collaborator Friedrich Engels.

Quotes

edit- Sorted chronologically

- Thus heaven I’ve forfeited, I know it full well. My soul, once true to God, is chosen for hell.

- “The Pale Maiden” (1837) ballad

- With disdain I will throw my gauntlet

- full in the face of the world,

- And see the collapse of this pygmy giant

- Whose fall will not stifle my ardour.

- Then I will wander godlike and victorious

- Through the ruins of the world.

- And, giving my words an active force,

- I will feel equal to the Creator.

- 1837, as quoted in Karl Marx: His Life and Thought by David McLellan, p. 22. See also M. Rubel, "Les Cahiers d'études de Karl Marx (1840-1853)", International Review of Social History (1957)

- The history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggles.

- As quoted in The Communist Manifesto (1848), p.2

- The executive of the modern State is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.

As quoted in the Communist Manifesto (1848) p. 7

- “And your education! Is not that also social, and determined by the social conditions under which you educate, by the intervention, direct or indirect, of society, by means of schools, etc.? The Communists have not invented the intervention of society in education; they do but seek to alter the character of that intervention, and to rescue education from the influence of the ruling class.”

- As quoted in The Communist Manifesto (21 February 1848), p19-20.

- It is a bad thing to perform menial duties even for the sake of freedom; to fight with pinpricks, instead of with clubs. I have become tired of hypocrisy, stupidity, gross arbitrariness, and of our bowing and scraping, dodging, and hair-splitting over words. Consequently, the government has given me back my freedom.

- Letter from Marx to Arnold Ruge (25 January 1843), after the Prussian government dissolved the newspaper Neue Rheinische Zeitung, of which Marx was the editor.

- Reason has always existed, but not always in a rational form.

- Letter from Marx to Arnold Ruge (September 1843)

- Indessen ist das gerade wieder der Vorzug der neuen Richtung, daß wir nicht dogmatisch die Welt antizipieren, sondern erst aus der Kritik der alten Welt die neue finden wollen. ... Ist die Konstruktion der Zukunft und das Fertigwerden für alle Zeiten nicht unsere Sache, so ist desto gewisser, was wir gegenwärtig zu vollbringen haben, ich meine die rücksichtslose Kritik alles Bestehenden, rücksichtslos sowohl in dem Sinne, daß die Kritik sich nicht vor ihren Resultaten fürchtet und ebensowenig vor dem Konflikte mit den vorhandenen Mächten.

- We do not dogmatically anticipate the world, but only want to find the new world through criticism of the old one. ... But, if constructing the future and settling everything for all times are not our affair, it is all the more clear what we have to accomplish at present: I am referring to ruthless criticism of all that exists, ruthless both in the sense of not being afraid of the results it arrives at and in the sense of being just as little afraid of conflict with the powers that be.

- Letter from Marx to Arnold Ruge (September 1843)

- We do not dogmatically anticipate the world, but only want to find the new world through criticism of the old one. ... But, if constructing the future and settling everything for all times are not our affair, it is all the more clear what we have to accomplish at present: I am referring to ruthless criticism of all that exists, ruthless both in the sense of not being afraid of the results it arrives at and in the sense of being just as little afraid of conflict with the powers that be.

- The only possible solution which will preserve Germany's honor and Germany's interest is, we repeat, a war with Russia.

- Marx-Engels Gesamt-Ausgabe, Erste Abteilung, Volume 7, March to December 1848, p. 304. Friedrich Engels. The Frankfurt Assembly Debates the Polish Question. Neue Rheinische Zeitung, No. 70, August 9, 1848.[1]

- History is not like some individual person, which uses men to achieve its ends. History is nothing but the actions of men in pursuit of their ends.

- The Holy Family, Ch. VI (1845).

- Die Philosophen haben die Welt nur verschieden interpretirt; es kommt aber darauf an, sie zu verändern.[2]

- The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.

- "Theses on Feuerbach" (1845), Thesis 11, Marx Engels Selected Works,(MESW), Volume I, p. 15; these words are also engraved upon his grave.

- First published as an appendix to the pamphlet Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy by Friedrich Engels (1886)

- Is that to say we are against Free Trade? No, we are for Free Trade, because by Free Trade all economical laws, with their most astounding contradictions, will act upon a larger scale, upon the territory of the whole earth; and because from the uniting of all these contradictions in a single group, where they will stand face to face, will result the struggle which will itself eventuate in the emancipation of the proletariat.

- Writing in the Chartist newspaper (1847), in Marx Engels Collected Works Vol 6, pg 290.

- A house may be large or small; as long as the neighboring houses are likewise small, it satisfies all social requirement for a residence. But let there arise next to the little house a palace, and the little house shrinks to a hut. The little house now makes it clear that its inmate has no social position at all to maintain, or but a very insignificant one; and however high it may shoot up in the course of civilization, if the neighboring palace rises in equal or even in greater measure, the occupant of the relatively little house will always find himself more uncomfortable, more dissatisfied, more cramped within his four walls.

- Wage Labour and Capital (December 1847), in Marx Engels Selected Works, Volume I, p. 163.

- [T]he very cannibalism of the counterrevolution will convince the nations that there is only one way in which the murderous death agonies of the old society and the bloody birth throes of the new society can be shortened, simplified and concentrated, and that way is revolutionary terror.

- "The Victory of the Counter-Revolution in Vienna," Neue Rheinische Zeitung, 7 November 1848.

- Did you not read our articles about the June revolution, and was not the essence of the June revolution the essence of our paper?

Why then your hypocritical phrases, your attempt to find an impossible pretext?

We have no compassion and we ask no compassion from you. When our turn comes, we shall not make excuses for the terror. But the royal terrorists, the terrorists by the grace of God and the law, are in practice brutal, disdainful, and mean, in theory cowardly, secretive, and deceitful, and in both respects disreputable.- The final issue of Neue Rheinische Zeitung (18 May 1849)''Marx-Engels Gesamt-Ausgabe, Vol. VI, p. 503,

- Variant translation: We are ruthless and ask no quarter from you. When our turn comes we shall not disguise our terrorism.

- Revolutions are the locomotives of history.

- [I]t is our interest and our task to make the revolution permanent until all the more or less propertied classes have been driven from their ruling positions, until the proletariat has conquered state power and until the association of the proletarians has progressed sufficiently far – not only in one country but in all the leading countries of the world – that competition between the proletarians of these countries ceases and at least the decisive forces of production are concentrated in the hands of the workers. Our concern cannot simply be to modify private property, but to abolish it, not to hush up class antagonisms but to abolish classes, not to improve the existing society but to found a new one.

- Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League in London (March 1850)

- Under no pretext should arms and ammunition be surrendered; any attempt to disarm the workers must be frustrated, by force if necessary.

- Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League in London, March 1850

- From your letter it would seem that, during your old man's visit to Manchester, you did not hear that a second document had appeared in the Kölnische Zeitung under the heading 'Der Bund der Kommunisten'. This was the piece we wrote jointly, 'Ansprache an den Bund'—au fond, nothing less than a plan of campaign against democracy.

- Karl Marx: Letter to Engels, July 13, 1851, Marx and Engels: Collected Works, Vol. 38, Letters 1844-51, Great Britain, Lawrence & Wishart, Electric Book, 2010, p. 384

- As for the commercial business, I can no longer make head or tail of it. At one moment crisis seems imminent and the City prostrated, the next everything is set fair. I know that none of this will have any impact on the catastrophe.

- Letter to Friedrich Engels (4 February 1852), quoted in The Collected Works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: Volume 39. Letters 1852–55 (2010), p. 32

- Society is undergoing a silent revolution, which must be submitted to, and which takes no more notice of the human existences it breaks down than an earthquake regards the houses it subverts. The classes and the races, too weak to master the new conditions of life, must give way. But can there be anything more puerile, more short-sighted, than the views of those Economists who believe in all earnest that this woeful transitory state means nothing but adapting society to the acquisitive propensities of capitalists, both landlords and money-lords?

- "Forced Emigration," New York Daily Tribune, 22 March 1853.

- The real point at issue always is Turkey in Europe – the great peninsula to the south of the Save and Danube. This splendid territory [the Balkans] has the misfortune to be inhabited by a conglomerate of different races and nationalities, of which it is hard to say which is the least fit for progress and civilization. Slavonians, Greeks, Wallachians, Arnauts, twelve millions of men, are all held in submission by one million of Turks, and up to a recent period, it appeared doubtful whether, of all these different races, the Turks were not the most competent to hold the supremacy which, in such a mixed population, could not but accrue to one of these nationalities.

- The Russian Menace to Europe, From Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, edited by Paul Blackstock and Bert Hoselitz, and published by George Allen and Unwin, London, 1953, pp 121-202. Originally published in New York Tribune (7 April 1853)

- Russia is decidedly a conquering nation, and was so for a century, until the great movement of 1789 called into potent activity an antagonist of formidable nature. We mean the European Revolution, the explosive force of democratic ideas and man’s native thirst for freedom. Since that epoch there have been in reality but two powers on the continent of Europe – Russia and Absolutism, the Revolution and Democracy. For the moment the Revolution seems to be suppressed, but it lives and is feared as deeply as ever. Witness the terror of the reaction at the news of the late rising at Milan. But let Russia get possession of Turkey, and her strength is increased nearly half, and she becomes superior to all the rest of Europe put together. Such an event would be an unspeakable calamity to the revolutionary cause. The maintenance of Turkish independence, or, in case of a possible dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the arrest of the Russian scheme of annexation, is a matter of the highest moment. In this instance the interests of the revolutionary Democracy and of England go hand in hand. Neither can permit the Tsar to make Constantinople one of his capitals, and we shall find that when driven to the wall, the one will resist him as determinedly as the other.

- The Russian Menace to Europe, From Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, edited by Paul Blackstock and Bert Hoselitz, and published by George Allen and Unwin, London, 1953, pp 121-202. Originally published in New York Tribune (7 April 1853)

- [B]y quarrelling amongst themselves, instead of confederating, Germans and Scandinavians, both of them belonging to the same great race, only prepare the way for their hereditary enemy, the Slav.

- The Eastern Question: A Reprint of Letters written 1853 –1856 dealing with the events of the Crimean War, edit., Eleanor Marx Aveling, London, Swan Sonnenschein & Co. (1897) p. 90 [3]

- England, it is true, in causing a social revolution in Hindostan, was actuated only by the vilest interests, and was stupid in her manner of enforcing them. But that is not the question. The question is, can mankind fulfil its destiny without a fundamental revolution in the social state of Asia? If not, whatever may have been the crimes of England she was the unconscious tool of history in bringing about that revolution.

- "The British Rule in India," New York Daily Tribune, 10 June 1853.

- England has to fulfill a double mission in India: one destructive, the other regenerating – the annihilation of old Asiatic society, and the laying the material foundations of Western society in Asia… When a great social revolution shall have mastered the results of the bourgeois epoch… and subjected them to the common control of the most advanced peoples, then only will human progress cease to resemble that hideous, pagan idol, who would not drink the nectar but from the skulls of the slain.

- "The Future Results of British Rule in India," New York Daily Tribune, 08 August 1853

- Thus we find every tyrant backed by a Jew, as is every Pope by a Jesuit. In truth, the cravings of oppressors would be hopeless, and the practicability of war out of the question, if there were not an army of Jesuits to smother thought and a handful of Jews to ransack pockets. […] the real work is done by the Jews, and can only be done by them, as they monopolize the machinery of the loanmongering mysteries by concentrating their energies upon the barter trade in securities… Here and there and everywhere that a little capital courts investment, there is ever one of these little Jews ready to make a little suggestion or place a little bit of a loan. […] Thus do these loans, which are a curse to the people, a ruin to the holders, and a danger to the governments, become a blessing to the houses of the children of Judah. This Jew organization of loan-mongers is as dangerous to the people as the aristocratic organization of landowners… The fortunes amassed by these loan-mongers are immense, but the wrongs and sufferings thus entailed on the people and the encouragement thus afforded to their oppressors still remain to be told. […] The fact that 1855 years ago Christ drove the Jewish moneychangers out of the temple, and that the moneychangers of our age enlisted on the side of tyranny happen again chiefly to be Jews, is perhaps no more than a historical coincidence. The loan-mongering Jews of Europe do only on a larger and more obnoxious scale what many others do on one smaller and less significant. But it is only because the Jews are so strong that it is timely and expedient to expose and stigmatize their organization.

- "The Russian Loan," New York Daily Tribune (4 January 1856); reprinted in full in The Eastern Question: A Reprint of Letters Written 1853-1856 Dealing with the Events of the Crimean War, edited by Eleanor Marx Aveling & Edward Aveling; S. Sonnenschein & Company, 1897, pp. 600-606

- What do you think of the aspect of the money market? … This time, by the by, the thing has assumed European dimensions such as have never been seen before, and I don't suppose we'll be able to spend much longer here merely as spectators. The very fact that I've at last got round to setting up house again and sending for my books seems to me to prove that the 'mobilisation' of our persons is AT HAND.

- Letter to Friedrich Engels (26 September 1856), quoted in The Collected Works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: Volume 40. Letters 1856–59 (2010), pp. 71–72

- As to the Delhi affair, [i.e., the Indian Rebellion of 1857 ] it seems to me that the English ought to begin their retreat as soon as the rainy season has set in in real earnest. Being obliged for the present to hold the fort for you as the Tribune's military correspondent I have taken it upon myself to put this forward. NB [nota bene; "take note"], on the supposition that the reports to date have been true. It's possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way.

- Letter to Friedrich Engels, dated 15 August 1857.

- There is something in human history like retribution; and it is a rule of historical retribution that its instrument be forged not by the offended, but by the offender himself. The first blow dealt to the French monarchy proceeded from the nobility, not from the peasants. The Indian revolt does not commence with the ryots, tortured, dishonoured and stripped naked by the British, but with the sepoys, clad, fed and petted, fatted and pampered by them.

- In an article written for the New York Daily Tribune, September 16, 1857 [4]

- Considering the optimistic turn taken by world trade AT THIS MOMENT…it is some consolation at least that the revolution has begun in Russia, for I regard the convocation of 'notables' to Petersburg as such a beginning. … [O]n the Continent revolution is imminent and will, moreover, instantly assume a socialist character.

- Letter to Friedrich Engels (8 October 1858), quoted in The Collected Works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: Volume 40. Letters 1856–59 (2010), pp. 346–347

- In the social production of their life, men enter into definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will; these relations of production correspond to a definite stage of development of their material forces of production. The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society — the real foundation, on which rises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life determines the social, political and intellectual life process in general. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness. [Es ist nicht das Bewußtsein der Menschen, das ihr Sein, sondern umgekehrt ihr gesellschaftliches Sein, das ihr Bewusstsein bestimmt.] At a certain stage of their development, the material productive forces in society come in conflict with the existing relations of production, or — what is but a legal expression for the same thing — with the property relations within which they have been at work before. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into fetters. Then begins an epoch of social revolution. With the change of the economic foundation the entire immense superstructure is more or less rapidly transformed. In considering such transformations a distinction should always be made between the material transformation of the economic conditions of production, which can be determined with the precision of natural science, and the legal, political, religious, aesthetic or philosophic — in short, ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out. Just as our opinion of an individual is not based on what he thinks of himself, so we can not judge of such a period of transformation by its own consciousness; on the contrary, this consciousness must be explained rather from the contradictions of material life, from the existing conflict between the social productive forces and the relations of production. No social order ever disappears before all the productive forces for which there is room in it have been developed; and new, higher relations of production never appear before the material conditions of their existence have matured in the womb of the old society itself. Therefore, mankind always sets itself only such tasks as it can solve; since, looking at the matter more closely, we will always find that the task itself arises only when the material conditions necessary for its solution already exist or are at least in the process of formation. In broad outlines we can designate the Asiatic, the ancient, the feudal, and the modern bourgeois modes of production as so many progressive epochs in the economic formation of society. The bourgeois relations of production are the last antagonistic form of the social process of production — antagonistic not in the sense of individual antagonism, but of one arising from the social conditions of life of the individuals; at the same time the productive forces developing in the womb of bourgeois society create the material conditions for the solution of that antagonism. This social formation constitutes, therefore, the closing chapter of the prehistoric stage of human society.

- Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859).

- The position of the revolutionary party in Germany is certainly difficult at the moment, but, with some critical analysis of the circumstances, clear nevertheless. As to the "governments," it is obvious from every point of view, if only for the sake of Germany's existence, that the demand must be put to them not to remain neutral, but, as you rightly say, to be patriotic. But the revolutionary point is to be given to the affair simply by emphasising the antagonism to Russia more strongly than the antagonism against Boustrapa.

- Letter to Friedrich Engels (18 May 1859), quoted in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Selected Correspondence, 1846–1895 (1943), p. 122

- The product of mental labor — science — always stands far below its value, because the labor-time necessary to reproduce it has no relation at all to the labor-time required for its original production.

- Addenda, "Relative and Absolute Surplus Value" in Economic Manuscripts (1861-63)

- [T]he Jewish Nigger, Lassalle… It is now quite plain to me — as the shape of his head and the way his hair grows also testify — that he is descended from the negroes who accompanied Moses’ flight from Egypt (unless his mother or paternal grandmother interbred with a nigger). Now, this blend of Jewishness and Germanness, on the one hand, and basic negroid stock, on the other, must inevitably give rise to a peculiar product. The fellow’s importunity is also nigger-like.

- Karl Marx to Friedrich Engels (Letter, July 30, 1862) in reference to his socialist political competitor, Ferdinand Lassalle. MECW Volume 41, p. 388; first published in Der Briefwechsel zwischen F. Engels und K. Marx, Stuttgart, 1913 and in full in MEGA, Berlin, 1930

- We are obviously heading for revolution—something I have never once doubted since 1850. The first act will include a by no means gratifying rehash of the stupidities of '48-'49. However, that's how world history runs its course, and one has to take it as one finds it.

- Letter to Ludwig Kugelmann (28 December 1862), quoted in The Collected Works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: Volume 41. Letters 1860–64 (2010), p. 437

- This much is certain, the ERA OF REVOLUTION has now FAIRLY OPENED IN EUROPE once more. And the general state of affairs is good.

- Letter to Friedrich Engels (13 February 1863), quoted in The Collected Works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: Volume 41. Letters 1860–64 (2010), p. 453

- I have just noticed in the 2nd edition of The Times that the Prussian Second Chamber has finally done something worthwhile. We shall soon have revolution.

- Letter to Friedrich Engels (21 February 1863), quoted in The Collected Works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: Volume 41. Letters 1860–64 (2010), p. 461

- Mit allen ihren Mängeln erscheint diese Konstitution mitten in der russisch−preußisch−österreichischen Barbarei als das einzige Freiheitswerk, das Osteuropa je selbständig hervorgebracht hat. Und sie ging ausschließlich von der bevorrechteten Klasse, dem Adel, aus. Die Weltgeschichte bietet kein andres Beispiel von ähnlichem Adel des Adels.

- Despite all its shortcomings, this Constitution looms against the background of Russo-Prusso-Austrian barbarism as the only work of liberty which Eastern Europe has ever created independently, and it emerged exclusively from the privileged class, from the nobility. The history of the world has never seen another example of such nobility of the nobility.

- On the Polish Constitution of May 3, 1791.

- "Poland, Prussia and Russia" (1863 manuscript). In Werner Conze and Dieter Hertz-Eichenrode (ed.) Manuskripte über die polnische Frage (1863-1864). Hague: Mouton, 1961.

Favourite maxim … Nihil humani a me alienum puto [Nothing human is alien to me]

Favourite motto … De omnibus dubitandum [Everything must be doubted].

- Your favourite virtue … Simplicity

Your favourite virtue in man … Strength

Your favourite virtue in woman … Weakness

Your chief characteristic … Singleness of purpose

Your idea of happiness … To fight

Your idea of misery … Submission

The vice you excuse most … Gullibility

The vice you detest most … Servility

Your aversion … Martin Tupper

Favourite occupation … Book-worming

Favourite poet … Shakespeare, Aeschylus, Goethe

Favourite prose-writer … Diderot

Favourite hero … Spartacus, Kepler

Favourite heroine … Gretchen [Heroine of Goethe's Faust]

Favourite flower … Daphne

Favourite colour … Red

Favourite name … Laura, Jenny

Favourite dish … Fish

Favourite maxim … Nihil humani a me alienum puto [Nothing human is alien to me, Terence]

Favourite motto … De omnibus dubitandum [Everything must be doubted].

- In its historical and political applications far more significant and pregnant than Darwin. For certain questions, such as nationality, etc., only here has a basis in nature been found. E.g., he corrects the Pole Duchinski, whose version of the geological differences between Russia and the Western Slav lands he does incidentally confirm, by saying not that the Russians are Tartars rather than Slavs, etc., as the latter believes, but that on the surface-formation predominant in Russia the Slav has been tartarised and mongolised; likewise (he spent a long time in Africa) he shows that the common negro type is only a degeneration of a far higher one.

- Letter to Friedrich Engels on P. Trémaux's 1865 work, Origine et Transformations de l'Homme et des autres Êtres (7 August 1866), quoted in Jon Elster, Making Sense of Marx (1985), p. 60

- Let us pass on to Prussia. Formerly a vassal of Poland, it grew to be a first-rate power only under the auspices of Russia and through the partition of Poland. If Prussia should lose its Polish prey tomorrow, it would sink back into Germany instead of absorbing it. In order to maintain itself as a power distinct from Germany it must lean for support on the Muscovite. Its recent increase of power, far from relaxing the bonds, has made them indissoluble. Besides this increase of power has increased Prussia’s antagonism with France and Austria. At the same time Russia is the pillar on which the arbitrary rule of the Hohenzollern dynasty and its feudal tenants rests. It is its safeguard against popular disaffection. Consequently Prussia is not a bulwark against Russia, but its predestined instrument for the invasion of France and the digestion of Germany.

- Poland’s European Mission. Speech delivered in London, probably to a meeting of the International’s General Council and the Polish Workers Society on 22 January 1867, text published in Le Socialisme, 15 March 1908.

- Everyone who knows anything of history also knows that great social revolutions are impossible without the feminine ferment. Social progress may be measured precisely by the social position of the fair sex (plain ones included).

- Letter to Ludwig Kugelmann, dated 12 December 1868.

- If conquest constitutes a natural right on the part of the few, the many have only to gather sufficient strength in order to acquire the natural right of reconquering what has been taken from them.

- The Abolition of Landed Property Letter to Robert Applegarth (3 December 1869)

- Instead of deciding once in three or six years which member of the ruling class was to misrepresent the people in Parliament, universal suffrage was to serve the people, constituted in Communes, as individual suffrage serves every other employer in the search for the workmen and managers in his business.

- From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs.

- The Criticism of the Gotha Program (1875)

- Variant translation: From each according to his ability, to each according to his need.

- Every step of real movement is more important than a dozen programmes.

- Letter to W. Bracke (5 May 1875)

- Neither of us cares a straw for popularity. A proof of this is for example, that, because of aversion to any personality cult, I have never permitted the numerous expressions of appreciation from various countries with which I was pestered during the existence of the International to reach the realm of publicity, and have never answered them, except occasionally by a rebuke. When Engels and I first joined the secret Communist Society we made it a condition that everything tending to encourage superstitious belief in authority was to be removed from the statutes.

- Remarks against personality cults from a letter to W. Blos (10 November 1877).

- Ramsgate is full of Jews and fleas.

- MEKOR IV, 490 (25 August 1879)

- If anything is certain, it is that I myself am not a Marxist

- Original: Ce qu'il y a de certain c'est que moi, je ne suis pas Marxiste.

- Marx quoted and translated by Engels (in an 1882 letter to Eduard Bernstein) about the peculiar Marxism which arose in France 1882. Original: "Ce qu'il y a de certain c'est que moi, je ne suis pas Marxiste" [5]

Reflections of a Youth on Choosing an Occupation (1835)

editReflections of a Young Man on The Choice of a Profession

- [The career a young man should choose should be] one that is most consonant with our dignity, one that is based on ideas of whose truth we are wholly convinced, one that offers us largest scope in working for humanity and approaching that general goal towards which each profession offers only one of the means: the goal of perfection … If he works only for himself he can become a famous scholar, a great sage, an excellent imaginative writer [Dichter], but never a perfected, a truly great man.

- in Karl Marx and World Literature (1976) by S. S. Prawer, p. 2.

- Everyone has a goal which appears to be great, at least to himself, and is great when deepest conviction, the innermost voice of the heart, pronounces it great. … This voice, however, is easily drowned out, and what we thought to be inspiration may have been created by the fleeting moment and again perhaps destroyed by it. … We must seriously ask ourselves, therefore, whether we are really inspired about a vocation, whether an inner voice approves of it, or whether the inspiration was a deception, whether that which we took as the Deity's calling to us was self-deceit. But how else could we recognize this except by searching for the source of our inspiration?

- Writings of the Young Marx on Philosophy and Society, L. Easton, trans. (1967), p. 36

- Everything great glitters, glitter begets ambition, and ambition can easily have caused the inspiration or what we thought to be inspiration. But reason can no longer restrain one who is lured by the fury of ambition. He tumbles where his vehement drive calls him; no longer does he choose his position, but rather chance and luster determine it.

- Then we are not called to the position where we can most shine. It is not the one which, in the long succession of years during which we may hold it, will never make us weary, subdue our zeal, or dampen our inspiration. Soon we shall see our wishes unfulfilled and our ideas unsatisfied.

- Writings of the Young Marx on Philosophy and Society, L. Easton, trans. (1967), p. 36

- We cannot always choose the vocation to which we believe we are called. Our social relations, to some extent, have already begun to form before we are in a position to determine them.

- Writings of the Young Marx on Philosophy and Society, L. Easton, trans. (1967), p. 37

- When we have weighed everything, and when our relations in life permit us to choose any given position, we may take that one which guarantees us the greatest dignity, which is based on ideas of whose truth we are completely convinced, which offers the largest field to work for mankind and approach the universal goal for which every position is only a means: perfection.

- Writings of the Young Marx on Philosophy and Society, L. Easton, trans. (1967), p. 38

- Only that position can impart dignity in which we do not appear as servile tools but rather create independently within our circle.

- Writings of the Young Marx on Philosophy and Society, L. Easton, trans. (1967), p. 38

- When we have chosen the vocation in which we can contribute most to humanity, burdens cannot bend us because they are only sacrifices for all. Then we experience no meager, limited, egotistic joy, but our happiness belongs to millions, our deeds live on quietly but eternally effective, and glowing tears of noble men will fall on our ashes.

- Writings of the Young Marx on Philosophy and Society, L. Easton, trans. (1967), p. 39

- Prometheus ist der vornehmste Heilige und Märtyrer im philosophischen Kalender.

- Prometheus is the most eminent saint and martyr in the philosophical calendar.

- Das Philosophisch-Werden der Welt [ist] zugleich ein Weltlich-Werden der Philosophie; ihre Verwirklichung [ist] zugleich ihr Verlust.

- For the world to become philosophic amounts to philosophy's becoming world-order reality; and it means that philosophy, at the same time that it is realized, disappears.

- The weapon of criticism obviously cannot replace the criticism of weapons. Material force can only be overthrown by material force, but theory itself becomes a material force when it has gripped the masses. Theory is capable of gripping the masses when it demonstrates ad hominem, and it demonstrates ad hominem, when it becomes radical. To be radical is to grasp things by the root, but for man the root is man himself. The clear proof of the radicalism of German theory, and hence of its political energy, is that it proceeds from the decisive positive abolition of religion.

- As quoted from David McLellan, Marx before Marxism, MacMillan, 1980, p. 150.

- The criticism of religion ends with the doctrine that man is the supreme being for man, hence the categorical imperative to overthrow all those conditions in which man is degraded, enslaved, neglected, contemptible being—conditions which can hardly be better described than in the exclamation of a Frenchman on the occasion of a proposed tax upon dogs: 'Wretched dogs! They want to treat you like men!'

- Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.

Criticism has plucked the imaginary flowers on the chain not in order that man shall continue to bear that chain without fantasy or consolation, but so that he shall throw off the chain and pluck the living flower.

- The foundation of irreligious criticism is: Man makes religion, religion does not make man.

- If I negate powdered wigs, I am still left with unpowdered wigs.

On the Jewish Question (1843)

edit- Zur Judenfrage – Full text online

- Every emancipation is a restoration of the human world and of human relationships to a man himself.

- Let us consider the actual, worldly Jew – not the Sabbath Jew, as Bauer does, but the everyday Jew. Let us not look for the secret of the Jew in his religion, but let us look for the secret of his religion in the real Jew. What is the secular basis of Judaism? Practical need, self-interest. What is the worldly religion of the Jew? Huckstering. What is his worldly God? Money. Very well then! Emancipation from huckstering and money, consequently from practical, real Judaism, would be the self-emancipation of our time. An organization of society which would abolish the preconditions for huckstering, and therefore the possibility of huckstering, would make the Jew impossible. His religious consciousness would be dissipated like a thin haze in the real, vital air of society. On the other hand, if the Jew recognizes that this practical nature of his is futile and works to abolish it, he extricates himself from his previous development and works for human emancipation as such and turns against the supreme practical expression of human self-estrangement.

- Bourgeois society continuously brings forth the Jew from its own entrails.

- as quoted in "Nationalism and Socialism: Marxist and Labor Theories of Nationalism to 1917", Horace B. Davis, New York: NY, Monthly Review Press (2009) p. 72. Original: Marx, "Zur Judenfrange" in "Werke", I, (1843) pp. 374-376.

- Political Economy regards the proletarian … like a horse, he must receive enough to enable him to work. It does not consider him, during the time when he is not working, as a human being. It leaves this to criminal law, doctors, religion, statistical tables, politics, and the beadle. … (1) What is the meaning, in the development of mankind, of this reduction of the greater part of mankind to abstract labor? (2) What mistakes are made by the piecemeal reformers, who either want to raise wages and thereby improve the situation of the working class, or — like Proudhon — see equality of wages as the goal of social revolution?.

- First Manuscript – Wages of Labour, p. 6.

- The worker's existence is thus brought under the same condition as the existence of every other commodity. The worker has become a commodity, and it is a bit of luck for him if he can find a buyer, And the demand on which the life of the worker depends, depends on the whim of the rich and the capitalists.

- Wages of Labor, p. 20.

- The fact that labour is external to the worker, i.e., it does not belong to his intrinsic nature; that in his work, therefore he does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and his mind. The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself.

- Estranged Labour, p. 30.

- Communism… is the genuine resolution of the antagonism between man and nature and between man and man; it is the true resolution of the conflict between existence and essence, objectification and self-affirmation, freedom and necessity, individual and species. It is the riddle of history solved and knows itself as the solution.

- Private Property and Communism, p. 43.

- The entire revolutionary movement necessarily finds both its empirical and its theoretical basis in the movement of private property – more precisely, in that of the economy. This material, immediately perceptible private property is the material perceptible expression of estranged human life. Its movement – production and consumption – is the perceptible revelation of the movement of all production until now, i.e., the realisation or the reality of man. Religion, family, state, law, morality, science, art, etc., are only particular modes of production, and fall under its general law. The positive transcendence of private property as the appropriation of human life, is therefore the positive transcendence of all estrangement – that is to say, the return of man from religion, family, state, etc., to his human, i.e., social, existence. Religious estrangement as such occurs only in the realm of consciousness, of man's inner life, but economic estrangement is that of real life; its transcendence therefore embraces both aspects. It is evident that the initial stage of the movement amongst the various peoples depends on whether the true recognised life of the people manifests itself more in consciousness or in the external world – is more ideal or real. Communism begins where atheism begins (Owen), but atheism is at the outset still far from being communism; indeed it is still for the most part an abstraction. The philanthropy of atheism is therefore at first only philosophical, abstract philanthropy, and that of communism is at once real and directly bent on action.

- Private Property and Communism

- Association, applied to land, shares the economic advantage of large-scale landed property, and first brings to realization the original tendency inherent in land-division, namely, equality. In the same way association also re-establishes, now on a rational basis, no longer mediated by serfdom, overlordship and the silly mysticism of property, the intimate ties of man with the earth, since the earth ceases to be an object of huckstering, and through free labour and free enjoyment becomes once more a true personal property of man.

- Rent of Land, p. 65.

- As for large landed property, its defenders have always, sophistically, identified the economic advantages offered by large-scale agriculture with large-scale landed property, as if it were not precisely as a result of the abolition of property that this advantage, for one thing, would receive its greatest possible extension, and, for another, only then would be of social benefit.

- Rent of Land, p. 66.

- Feuerbach is the only one who has a serious, critical attitude to the Hegelian dialectic and who has made genuine discoveries in this field. He is in fact the true conqueror of the old philosophy. The extent of his achievement, and the unpretentious simplicity with which he, Feuerbach, gives it to the world, stand in striking contrast to the opposite attitude (of the others). Feuerbach's great achievement is: (1) The proof that philosophy is nothing else but religion rendered into thought and expounded by thought, i.e., another form and manner of existence of the estrangement of the essence of man; hence equally to be condemned;(2) The establishment of true materialism and of real science, by making the social relationship of "man to man" the basic principle of the theory; (3) His opposing of the negation of the negation, which claims to be the absolute positive, the self-supporting positive, positively based on itself.

- Critique of the Hegelian Dialectic and Philosophy as a Whole, p. 64.

- Der Philosoph legt sich – also selbst eine abstrakte Gestalt des entfremdeten Menschen – als den Maßstab der entfremdeten Welt an.

- The philosopher, who is himself an abstract form of alienated man, sets himself up as the measure of the alienated world.

- In order to abolish the idea of private property, the idea of communism is completely sufficient. It takes actual communist action to abolish actual private property. History will com to it; and this movement, which in theory we already know to be a self-transcending movement, will constitute in actual fact a very severe and protracted process. But we must regard it as a real advance to have gained beforehand a consciousness of the limited character a well as of the goal of this historical movement - and a consciousness which reaches out beyond it.

- p. 99, The Marx-Engels Reader

- When communist workmen associate with one another, theory, propaganda, etc., is their first end. But at the same time, as a result of this association, they acquire a new need - the need for society - and what appears as a means becomes an end. You can observe this practical processing its most splendid results whenever you see French socialist workers together. Such things as smoking, drinking, eating, etc., are no longer means of contact or means that bring together. Company, association, and conversation, which again has society as its end, are enough for them; the brotherhood of man is on mere phase with them, but a fact of life, and the nobility of man shines upon us from their work-hardened bodies.

- "The Meaning of Human Requirements"

- p.99-100,The Marx-Engels Reader

- Private property has made us so stupid and one-sided that an object is only ours when we have it - when it exists for us as capital, or when it is directly possessed, eaten, drunk, worn, inhabited, etc., - in short, when it is used by us. Although private property itself again conceives all these direct realizations of possession as means of life, and the life which they serve as means is the life of private property - labour and conversion into capital. In place of all these physical and mental senses there has therefore come the sheer estrangement of all these senses – the sense of having. The human being had to be reduced to this absolute poverty in order that he might yield his inner wealth to the outer world.

- p. 87, The Marx-Engels Reader

- Money, then, appears as this overturning power both against the individual and against the bonds of society, etc., which claim to be essences in themselves. It transforms fidelity into infidelity, love into hate, hate into love, virtue into vice, vice into virtue, servant into master, master into servant, idiocy into intelligence and intelligence into idiocy.

- "The Power of Money in Bourgeois Society"

- p. 105, The Marx-Engels Reader

- He who can buy bravery is brace, though a coward. As money is not exchanged for anyone specific quality, for any one specific thing, or for any particular human essential power, but for the entire objective world of man and nature, from the standpoint of its possessor it therefore serves to exchange every property for every other, even contradictory, property and object: it is the fraternization of impossibilities. It makes contradictions embrace.

- p. 105, The Marx-Engels Reader

- The worker becomes all the poorer the more wealth he produces, the more his production increases in power and range. The worker becomes an ever cheaper commodity the more commodities he creates. With the increasing value of the world of things proceeds in direct proportion the devaluation of the world of men. Labour produces not only commodities; it produces itself and the worker as a commodity - and does so in the proportion in which it produces commodities generally.

- p. 71, The Marx-Engels Reader

- The product of labour is labour which has been congealed in an object, which has become material: it is the objectification of labour. Labour's realization is its objectification.

- p. 71, The Marx-Engels Reader

The Holy Family (1845)

edit- Undeterred by this examination, the French Revolution gave rise to ideas which led beyond the ideas of the entire old world order. The revolutionary movement which began in 1789 in the Cercle Social, which in the middle of its course had as its chief representatives Leclerc and Roux, and which finally with Babeuf’s conspiracy was temporarily defeated, gave rise to the communist idea which Babeuf’s friend Buonarroti re-introduced in France after the Revolution of 1830. This idea, consistently developed, is the idea of the new world order.

- Chapter 6, 3

The German Ideology (1845-1846)

edit- Die Deutsche Ideologie by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels – Full text online

- Through the emancipation of private property from the community, the State has become a separate entity, beside and outside civil society; but is it nothing more than the form of organization which the bourgeois necessarily adopt both for internal and external purposes, for the mutual guarantee of their property and interests.

- Part One

- The Marx-Engels Reader, p. 187

- Manufacture was all the time sheltered by protective duties in the hoe market, by monopolies in the colonial market, and broad as much as possible by differential duties.

- ibid, pp. 183

- In civil law the existing property relationships are declared to be the result of the general will. The jus utendi et abutendi itself asserts on the one hand the fact that private property has become entirely independent of the community, and on the other the illusion that private property itself is based solely on the private will, the arbitrary disposal.

- ibid, pp. 188

- Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things. The conditions of this movement result from the premises now in existence.

- Vol. I, Part 1.

- For as soon as the distribution of labour comes into being, each man has a particular exclusive sphere of activity, which is forced upon him and from which he cannot escape. He is a hunter, a fisherman, a shepherd, or a critical critic and must remain so if he does not wish to lose his means of livelihood; while in communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, to fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner, just as I have in mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, shepherd or critic.

- Vol. 1, Part 1.

- The first premise of all human history is, of course, the existence of living human individuals. Thus the first fact to be established is the physical organisation of these individuals and their consequent relation to the rest of nature.

- Volume I; Part 1; "Feuerbach. Opposition of the Materialist and Idealist Outlook"; Section A, "Idealism and Materialism".

- The fact is, therefore, that definite individuals who are productively active in a definite way enter into these definite social and political relations. Empirical observation must in each separate instance bring out empirically, and without any mystification and speculation, the connection of the social and political structure with production. The social structure and the state are continually evolving out of the life-process of definite individuals, but of individuals, not as they appear in their own or other people's imagination, but as they really are; i.e. as they are effective, produce materially, and are active under definite material limits, presuppositions and conditions independent of their will.

The production of ideas, of conceptions, of consciousness, is at first directly interwoven with the material activity and the material intercourse of men, the language of real life. Conceiving, thinking, the mental intercourse of men, appear at this stage as the direct efflux of their material behaviour. The same applies to mental production as expressed in the language of the politics, laws, morality, religion, metaphysics of a people. Men are the producers of their conception, ideas, etc. — real, active men, as they are conditioned by a definite development of their productive forces and of the intercourse corresponding to these, up to its furthest forms. Consciousness can never be anything else than conscious existence, and the existence of men is their actual life-process. If in all ideology men and their circumstances appear upside down as in a camera obscura, this phenomenon arises just as much from their historical life-process as the inversion of objects on the retina does from their physical life-process.

- Where speculation ends — in real life — there real, positive science begins: the representation of the practical activity, of the practical process of development of men. Empty talk about consciousness ceases, and real knowledge has to take place. When reality is depicted, philosophy as an independent branch of activity loses its medium of existence. At the best its place can only be taken by a summing-up of the most general results, abstractions which arise from the observation of the historical development of men. Viewed apart from real history, these abstractions have in themselves no value whatsoever. They can only serve to facilitate the arrangement of historical material, to indicate the sequence of its separate strata. But they by no means afford a recipe or schema, as does philosophy, for neatly trimming the epochs of history. On the contrary, our difficulties begin only when we set about the observation and the arrangement — the real depiction — of our historical material, whether of a past epoch or of the present.

- Vol. I, Part 1, [The Materialist Conception of History].

- Communism differs from all previous movements in that it overturns the basis of all earlier relations of production and intercourse, and for the first time consciously treats all natural premises as the creatures of hitherto existing men, strips them of their natural character and subjugates them to the power of the united individuals. Its organisation is, therefore, essentially economic, the material production of the conditions of this unity; it turns existing conditions into conditions of unity. The reality, which communism is creating, is precisely the true basis for rendering it impossible that anything should exist independently of individuals, insofar as reality is only a product of the preceding intercourse of individuals themselves.

- Vol. I, Part 4.

- Nicht das Bewußtsein bestimmt das Leben, sondern das Leben bestimmt das Bewußtsein.

- It is in fact not the consciousness dominating life but the very life dominating consciousness.

- Vol. III, 27.

- Sprache entsteht, wie das Bewußtsein, erst aus dem Bedürfnis, der Notdurft des Verkehrs mit anderen Menschen.

- Language comes into being, like consciousness, from the basic need, from the scantiest intercourse with other human.

- Vol. III, 30.

- Philosophy stands in the same relation to the study of the actual world as masturbation to sexual love.

- The German Ideology, International Publishers, ed. Chris Arthur, p. 103.

- For each new class which puts itself in the place of one ruling before it, is compelled, merely in order to carry through its aim, to represent its interests the common interest of all the members of society, that is, sality, and represent them as the only rational, universally valid ones. The class making a revolution appears from the very start, if only because it is opposed to a class, not as a class but as the representative of the whole of society; it appears as the whole mass of society confronting the one ruling class.

- "Concerning the production of Consciousness"

- Thus, while the refugee serfs only wished to be free to develop and assert those conditions of existence which were already there, and hence, in the end, only arrived at free labour, the proletarians, if they are to assert themselves as individuals, will have to abolish the very condition of their existence hitherto (which has, moreover, been that of all society up to the present), namely, labour. Thus they find themselves directly opposed to the form in which, hitherto, the individuals, of which society consists, have given themselves collective expression, that is, the State. In order, therefore, to assert themselves as individuals, they must overthrow the State.

- "Communism. The Production of the Form of Intercourse Itself",

- The Marx-Engels Reader

The Communist Manifesto (1848)

edit- Das Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

- For more quotes from and about this document, see The Communist Manifesto

- A spectre is haunting Europe; the spectre of Communism.

- Preamble, paragraph 1, line 1.

- It is high time that Communists should openly, in the face of the whole world, publish their views, their aims, their tendencies, and meet this nursery tale of the spectre of Communism with a Manifesto of the party itself.

- Preamble, paragraph 3.

- The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.

- Section 1, paragraph 1, lines 1-2.

- The bourgeoisie has stripped of its halo every occupation hitherto honoured and looked up to with reverent awe. It has converted the physician, the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science, into its paid wage labourers.

- Section 1, paragraph 14.

- All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.

- Section 1, paragraph 18, lines 12-14.

- The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the whole surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere.

- Section 1, paragraph 19

- These labourers, who must sell themselves piecemeal, are a commodity, like every other article of commerce, and are consequently exposed to all the vicissitudes of competition, to all the fluctuations of the market.

- Section 1, Paragraph 30

- The theory of Communism may be summed up in the single sentence: Abolition of private property.

- Section 2, paragraph 13.

- There are, besides, eternal truths, such as Freedom, Justice, etc., that are common to all states of society. But Communism abolishes eternal truths, it abolishes all religion, and all morality, instead of constituting them on a new basis; it therefore acts in contradiction to all past historical experience.

- Section 2, paragraph 63

- In place of the bourgeois society, with its classes and class antagonisms, shall we have an association, in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.

- Section 2, paragraph 72 (last paragraph).

- The immediate aim of the Communists is the same as that of all the other proletarian parties: Formation of the proletariat into a class, overthrow of the bourgeois supremacy, conquest of political power by the proletariat.

- Section 2 paragraph 7.

- The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims. They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win.

WORKING MEN OF ALL COUNTRIES, UNITE!- Section 4, paragraph 11 (last paragraph)

- Variant translation: Workers of the world, unite!

The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852)

edit- Der achtzehnte Brumaire des Louis Napoleon (1852), accessed via w:de:Projekt Gutenberg-DE (23 August 2024)

The title of this work relates the 1851 coup of Louis Napoleon to the coup of 18 Brumaire, Year VIII (9 November 1799) by his uncle Napoleon Bonaparte

- Hegel bemerkte irgendwo, daß alle großen weltgeschichtlichen Tatsachen und Personen sich sozusagen zweimal ereignen. Er hat vergessen, hinzuzufügen: das eine Mal als Tragödie, das andere Mal als Farce.

- This has been compared to Horace Walpole's statement: "This world is a comedy to those that think, a tragedy to those that feel."

- Hegel says somewhere that that great historic facts and personages recur twice. He forgot to add: "Once as tragedy, and again as farce."

- The Tories in England long imagined that they were enthusiastic about monarchy, the church, and the beauties of the old English Constitution, until the day of danger wrung from them the confession that they are enthusiastic only about ground rent.

- Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living. And just as they seem to be occupied with revolutionizing themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honored disguise and borrowed language. Thus Luther put on the mask of the Apostle Paul, the Revolution of 1789-1814 draped itself alternately in the guise of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, and the Revolution of 1848 knew nothing better to do than to parody, now 1789, now the revolutionary tradition of 1793-95. In like manner, the beginner who has learned a new language always translates it back into his mother tongue, but he assimilates the spirit of the new language and expresses himself freely in it only when he moves in it without recalling the old and when he forgets his native tongue.

When we think about this conjuring up of the dead of world history, a salient difference reveals itself. Camille Desmoulins, Danton, Robespierre, St. Just, Napoleon, the heroes as well as the parties and the masses of the old French Revolution, performed the task of their time – that of unchaining and establishing modern bourgeois society – in Roman costumes and with Roman phrases.

Grundrisse (1857-1858)

edit- Grundrisse der Kritik der politischen Ökonomie/Rohentwurf [A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy] (1857/58)

- The object before us, to begin with, material production.

- Introduction, p. 3, first text page, first line.

- The industrial peak of a people when its main concern is not yet gain, but rather to gain.

- Introduction, p. 7.

- Consumption is also immediately production, just as in nature the consumption of the elements and chemical substances is the production of the plant.

- Introduction, p. 10.

- No production without a need. But consumption reproduces the need.

- Introduction, p. 12.

- The object of art — like every other product — creates a public which is sensitive to art and enjoys beauty.

- Introduction, p. 12.

- The individual produces an object and, by consuming it, returns to himself, but returns as a productive and self reproducing individual. Consumption thus appears as a moment of production.

- Introduction, p. 14.

- But there is a devil of a difference between barbarians who are fit by nature to be used for anything, and civilized people who apply them selves to everything.

- Introduction, p. 25.

- What chance has Vulcan against Roberts & Co., Jupiter against the lightning-rod and Hermes against the Credit Mobilier? All mythology overcomes and dominates and shapes the forces of nature in the imagination and by the imagination; it therefore vanishes with the advent of real mastery over them.

- Introduction, p. 30.

- From another side: is Achilles possible with powder and lead? Or the Iliad with the printing press, not to mention the printing machine? Do not the song and saga of the muse necessarily come to an end with the printer's bar, hence do not the necessary conditions of epic poetry vanish?

- Introduction, p. 31.

- A man cannot become a child again, or he becomes childish.

- Introduction, p. 31.

- What's sauce for the gander is sauce for the goose.

- Introduction, p. 37.

- Supply and demand constantly determine the prices of commodities; never balance, or only coincidentally; but the cost of production, for its part, determines the oscillations of supply and demand.

- Notebook I, The Chapter on Money, p. 58.

- The unity is brought about by force.

- Notebook I, The Chapter on Money, p. 70.

- Each pursues his private interest and only his private interest; and thereby serves the private interests of all, the general interest, without willing it or knowing it. The real point is not that each individual's pursuit of his private interest promotes the totality of private interests, the general interest. One could just as well deduce from this abstract phrase that each individual reciprocally blocks the assertion of the others' interests, so that, instead of a general affirmation, this war of all against all produces a general negation.

- Notebook I, The Chapter on Money, p. 76.

- Die Ideen existieren nicht getrennt von der Sprache.

- Ideas do not exist separately from language.

- Notebook I, The Chapter on Money, p. 83.

- Money does not arise by convention, any more than the state does. It arises out of exchange, and arises naturally out of exchange; it is a product of the same.

- Notebook I, The Chapter on Money, p. 85.

- Money appears as measure (in Homer, e.g. oxen) earlier than as medium of exchange,because in barter each commodity is still its own medium of exchange. But it cannot be its own or its own standard of comparison.

- Notebook I, The Chapter on Money, p. 93.

- The circulation of commodities is the original precondition of the circulation of money.

- Notebook I, The Chapter on Money, p. 107.

- Since labour is motion, time is its natural measure.

- Notebook I, The Chapter on Money, p. 125.

- Exchange value forms the substance of money, and exchange value is wealth.

- Notebook II, The Chapter on Money, p. 141.

- Money is therefore not only the object but also the fountainhead of greed.

- Notebook II, The Chapter on Money, p. 142.

- In fact of course, this 'productive' worker cares as much about the crappy shit he has to make as does the capitalist himself who employs him, and who also couldn't give a damn for the junk.

- Notebook II, The Chapter on Capital, p. 193.

- Surplus value is exactly equal to surplus labour; the increase of the one [is] exactly measured by the diminution of necessary labour.

- Notebook III, The Chapter on Capital, p. 259.

- (That is it!)

- Notebook III, The Chapter on Capital, p. 260 (In English in the original).

- Capitals accumulate faster than the population; thus wages; thus population; thus grain prices; thus the difficulty of production and hence the exchange values.

- Notebook III, The Chapter on Capital, p. 271.

- The devil take this wrong arithmetic. But never mind.

- Notebook IV, The Chapter on Capital, p. 297.

- An increase in the productivity of labour means nothing more than that the same capital creates the same value with less labour, or that less labour creates the same product with more capital.

- Notebook IV, The Chapter on Capital, p. 308.

- Luxury is the opposite of the naturally necessary.

- Notebook V, The Chapter on Capital, p. 448.

- Although usury is itself a form of credit in its bourgeoisified form, the form adapted to capital, in its pre-bourgeois form it is rather the expression of the lack of credit.

- Notebook V, The Chapter on Capital, p. 455.

- The circulation of capital realizes value, while living labour creates value.

- Notebook V, The Chapter on Capital, p. 463.

- Something that is merely negative creates nothing.

- Notebook VI, The Chapter on Capital, p. 532.

- Money is itself a product of circulation.

- Notebook VI, The Chapter on Capital, p. 579.

- Die Gesellschaft besteht nicht aus Individuen, sondern drückt die Summe der Beziehungen, Verhältnisse aus, worin diese Individuen zueinander stehn.

- Any society does not consist of individuals but expresses the sum of relationships [and] conditions that the individual actor is forming.

- MEW Vol. 42, p. 176.

- Beauty is the main positive form of the aesthetic assimilation of reality, in which aesthetic ideal finds it direct expression…

- About Beauty

- Die Natur baut keine Maschinen, keine Lokomotiven, Eisenbahnen, electric telegraphs, selfacting mules etc. Sie sind Produkte der menschlichen Industrie; natürliches Material, verwandelt in Organe des menschlichen Willens über die Natur oder seiner Betätigung in der Natur. Sie sind von der menschlichen Hand geschaffene Organe des menschlichen Hirns; vergegenständliche Wissenskraft. Die Entwicklung des capital fixe zeigt an, bis zu welchem Grade das allgemeine gesellschaftliche Wissen, knowledge, zur unmittelbaren Produktivkraft geworden ist und daher die Bedingungen des gesellschaftlichen Lebensprozesses selbst unter die Kontrolle des general intellect gekommen, und ihm gemäß umgeschaffen sind.

- Nature builds no machines, no locomotives, railways, electric telegraphs, self-acting mules etc. These are products of human industry; natural material transformed into organs of the human will over nature, or of human participation in nature. They are organs of the human brain, created by the human hand; the power of knowledge, objectified. The development of fixed capital indicates to what degree general social knowledge has become a direct force of production, and to what degree, hence, the conditions of the process of social life itself have come under the control of the general intellect and been transformed in accordance with it.

- Notebook VII, The Chapter on Capital, p. 626.

- The development of fixed capital indicates in still another respect the degree of development of wealth generally, or of capital…

The creation of a large quantity of disposable time apart from necessary labour time for society generally and each of its members (i.e. room for the development of the individuals' full productive forces, hence those of society also), this creation of not-labour time appears in the stage of capital, as of all earlier ones, as not-labour time, free time, for a few. What capital adds is that it increases the surplus labour time of the mass by all the means of art and science, because its wealth consists directly in the appropriation of surplus labour time; since value directly its purpose, not use value. It is thus, despite itself, instrumental in creating the means of social disposable time, in order to reduce labour time for the whole society to a diminishing minimum, and thus to free everyone's time for their own development. But its tendency always, on the one side, to create disposable time, on the other, to convert it into surplus labour…

The mass of workers must themselves appropriate their own surplus labour. Once they have done so – and disposable time thereby ceases to have an antithetical existence – then, on one side, necessary labour time will be measured by the needs of the social individual, and, on the other, the development of the power of social production will grow so rapidly that, even though production is now calculated for the wealth of all, disposable time will grow for all. For real wealth is the developed productive power of all individuals. The measure of wealth is then not any longer, in any way, labour time, but rather disposable time. Labour time as the measure of value posits wealth itself as founded on poverty, and disposable time as existing in and because of the antithesis to surplus labour time; or, the positing of an individual's entire time as labour time, and his degradation therefore to mere worker, subsumption under labour. The most developed machinery thus forces the worker to work longer than the savage does, or than he himself did with the simplest, crudest tools.- Notebook VII, The Chapter on Capital, pp. 628–629.

- The economic concept of value does not occur in antiquity.

- Notebook VII, The Chapter on Capital, p. 696.

- It might otherwise appear paradoxical that money can be replaced by worthless paper; but that the slightest alloying of its metallic content depreciates it.

- Notebook VII, The Chapter on Capital, p. 734.

- Is a fixed income not a good thing? Does not everyone love to count on a sure thing? Especially every petty-bourgeois, narrow-minded Frenchman? the 'ever needy' man?

- (Bastiat and Carey), pp. 809–810.

- It is impossible to pursue this nonsense any further.

- (Bastiat and Carey), p. 813 (last text page, second last line).

Comments on the North American Events (1862)

edit- Comments on the North American Events, Die Presse (12 October 1862)

- The South has conquered nothing — but a graveyard.

- Reason nevertheless prevails in world history.

- Lincoln's proclamation is even more important than the Maryland campaign. Lincoln is a sui generis figure in the annals of history. He has no initiative, no idealistic impetus, cothurnus, no historical trappings. He gives his most important actions always the most commonplace form. Other people claim to be "fighting for an idea", when it is for them a matter of square feet of land. Lincoln, even when he is motivated by, an idea, talks about "square feet". He sings the bravura aria of his part hesitatively, reluctantly and unwillingly, as though apologising for being compelled by circumstances "to act the lion". The most redoubtable decrees — which will always remain remarkable historical documents-flung by him at the enemy all look like, and are intended to look like, routine summonses sent by a lawyer to the lawyer of the opposing party, legal chicaneries, involved, hidebound actiones juris. His latest proclamation, which is drafted in the same style, the manifesto abolishing slavery, is the most important document in American history since the establishment of the Union, tantamount to the tearing up of the old American Constitution.

- Lincoln's place in the history of the United States and of mankind will, nevertheless, be next to that of Washington!

- Lincoln is not the product of a popular revolution. This plebeian, who worked his way up from stone-breaker to Senator in Illinois, without intellectual brilliance, without a particularly outstanding character, without exceptional importance-an average person of good will, was placed at the top by the interplay of the forces of universal suffrage unaware of the great issues at stake. The new world has never achieved a greater triumph than by this demonstration that, given its political and social organisation, ordinary people of good will can accomplish feats which only heroes could accomplish in the old world!

- Hegel once observed that comedy is in act superior to tragedy and humourous reasoning superior to grandiloquent reasoning. Although Lincoln does not possess the grandiloquence of historical action, as an average man of the people he has its humour.

Marx and Engels: 1860-1864

edit- I'm amused that Darwin, at whom I've been taking another look, should say that he also applies the ‘Malthusian’ theory to plants and animals, as though in Mr Malthus’s case the whole thing didn’t lie in its not being applied to plants and animals, but only — with its geometric progression — to humans as against plants and animals. It is remarkable how Darwin rediscovers, among the beasts and plants, the society of England with its division of labour, competition, opening up of new markets, ‘inventions’ and Malthusian ‘struggle for existence’. It is Hobbes’ bellum omnium contra omnes and is reminiscent of Hegel’s Phenomenology, in which civil society figures as an ‘intellectual animal kingdom’, whereas, in Darwin, the animal kingdom figures as civil society.

- Marx, Karl. [1862] 1985. “Marx to Engels in Manchester, 18 June 1862.” Pp. 380–381 in Karl Marx Frederick Engels Collected Works, Marx and Engels: 1860–1864. Moscow: Progress Publishers. "Source: MECW Volume 41, p. 380; First published: in Der Briefwechsel zwischen F. Engels und K. Marx, Stuttgart, 1913."

Das Kapital (Buch I) (1867)

edit- Capital, Volume I (Capital: A Critique of Political Economy) (1867)

- Every beginning is difficult, holds in all sciences.

- Author's prefaces to the First Edition.

- I pre-suppose, of course, a reader who is willing to learn something new and therefore to think for himself.

- Author's prefaces to the First Edition.

- The country that is more developed industrially only shows, to the less developed, the image of its own future.

- Author's prefaces to the First Edition.

- We suffer not only from the development of capitalist production, but also from the incompleteness of that development. Alongside the modern evils, we are oppressed by a whole series of inherited evils, arising from the passive survival of archaic and outmoded modes of production, with their accompanying train of anachronistic social and political relations. We suffer not only from the living, but from the dead. Le mort saisit le vif!

- Preface to the First Edition, Capital Volume 1, Peinguin Classics edition 1976.

- Perseus wore a magic cap that the monsters he hunted down might not see him.

We draw the magic cap down over eyes and ears as a make-believe that there are no monsters.- Author's prefaces to the First Edition.

- The most violent, mean and malignant passions of the human breast, the Furies of private interest.

- Author's prefaces to the First Edition.

- The commodity is first of all, an external object, a thing which through its qualities satisfies human needs of whatever kind. The nature of these needs, whether they arise, for example, from the stomach, or the imagination, makes no difference. Nor does it matter here how the thing satisfies man's need, whether directly as a means of subsistence, i.e. an object of consumption, or indirectly as a means of production

- Vol. I, Ch. 1, Section 1, pg. 41.

- To discover the various use of things is the work of history.

- Vol. I, Ch. 1, Section 1, pg. 42.