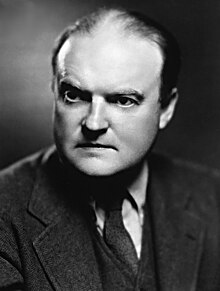

Edmund Wilson

American writer, literary and social critic, and noted man of letters (1895-1972)

Edmund Wilson (8 May 1895 – 12 June 1972) was an American writer and literary critic.

Quotes

edit- There is really no way of considering a book independently of one's special sensations in reading it on a particular occasion. In this as in everything else one must allow a certain relativity. In a sense, one can never read the book that the author originally wrote, and one can never read the same book twice.

- The Triple Thinkers (1938), Preface, p. ix, [ 1948 Oxford University Press edition]

- Education, the last hope of the liberal in all periods.

- To the Finland Station : A Study in the Acting and Writing of History (1940), Part I, Ch. 5: Michelet Between Nationalism and Socialism, p. 36, [1972 Farrar Straus & Giroux edition, ISBN 1568495749/1145]

- It may be that there is nothing more demoralizing than a small but adequate income.

- Memoirs of Hecate County (1946), Ch. 4, p. 136, [New York Review Books Classics (2004)]

- Marxism is the opium of the intellectuals.

- Memoirs of Hecate County (1946), Ch. 5, p. 340, [New York Review Books Classics (2004)]; Karl Marx, in his Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right (1843-4), wrote "Religion…is the opium of the people" ("Die Religion…ist das Opium des Volkes"). Wilson was not the first writer to turn Marx’s statement on its head: Evelyn Waugh published a review of Harold Laski's Faith, Reason and Civilization in The Tablet, 22nd April 1944, under the headline "Marxism, the Opiate of the People". In 1955 the French philosopher Raymond Aron wrote a book on Marxism called L'Opium des intellectuels, thus Wilson's line is often attributed to him.

- I believe, that certain people — especially, perhaps, in Britain — have a lifelong appetite for juvenile trash. … You can see it in the tone they fall into when they talk about Tolkien in print: they bubble, they squeal, they coo; they go on about Malory and Spenser — both of whom have a charm and a distinction that Tolkien has never touched.

As for me, if we must read about imaginary kingdoms, give me James Branch Cabell's Poictesme. He at least writes for grown-up people, and he does not present the drama of life as a showdown between Good People and Goblins. He can cover more ground in an episode that lasts only three pages than Tolkien is able to in one of this twenty-page chapters, and he can create a more disquieting impression by a reference to something that is never described than Tolkien through his whole demonology.- "Oo, Those Awful Orcs!" : A review of The Fellowship of the Ring, The Nation (14 April 1956)

- The more I have thought about Figures of Earth — and its sequel The Silver Stallion — the more remarkable they have come to seem. Looking back, one can now understand the abrupt fluctuations of Cabell's fame. … Published when Cabell was forty-two, the chronicle of Manuel the Redeemer was not a book for the Young nor was it a book in the mood of the twenties. The story of the ambitious man of action who is cowardly, malignant and treacherous and who does not even enjoy very much what his crimes and double-dealing have won him, but who is rapidly, after his death, transformed into a great leader, a public benefactor and a saint, has the fatal disadvantage for a novel that the reader finds no inducement to identify himself with its central figure. Yet I am now not sure that this merciless chronicle in which all the values are negative except the naked human will, is not one of the best things of its kind in literature — on a plane, perhaps, with Flaubert and Swift.

- "James Branch Cabell 1897 - 1958" (1958), later published in The Bit Between My Teeth: A Literary Chronicle Of 1950-1965 (1966), p. 322

Quotes about Wilson

edit- He was, as painted, aristocratic, beyond any writer I've met, but in a Jeffersonian-American way that brooked no artificial distinctions. There was no cheap way you could impress him... It was a particular strength of his as a critic that he was not even impressed by the Dead as such. He could write of living authors in precisely the same tones, and applying the same standards, as he used for the Classics.

- Wilfrid Sheed, The Good Word & Other Words (1978), Part I, ch. 1: "Edmund Wilson, 1895-1972," p. 6, [1980 Penguin edition ISBN 0-14-005497-9]

- Wilson was not, in the academic sense, a scholar or historian. He was an enormous reader, one of those readers who are perpetually on the scent from book to book. He was the old-style man of letters, but galvanized and with the iron of purpose in him.

- V. S. Pritchett, The Tale Bearers: English and American Writers (1980), "Edmund Wilson: Towards Revolution," p. 141, [ Random House, ISBN 0-394-74683-X]

- He was the perfect autodidact. He wanted to know it all.

- Gore Vidal, "Edmund Wilson: This Critic and This Gin and These Shoes," The New York Review of Books (25 September 1980), later published in The Second American Revolution and Other Essays, 1976-1982 (1982), p. 32, [ 1983 Vintage edition ISBN 0-394-71379-6]

- Wilson is not like other critics; some critics are boring even when they are original; he fascinates even when he is wrong.

- Alfred Kazin, in Benet's Reader's Encyclopedia of American Literature (1991), p. 1146