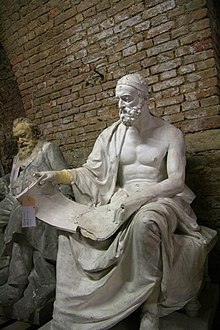

Polybius

ancient Greek historian

Polybius [Πολύβιος] (c. 203 BC – 120 BC) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period noted for his work The Histories, which covered the period of 264–146 BC in detail. The work describes the rise of the Roman Republic to the status of dominance in the ancient Mediterranean world and includes his eyewitness account of the Sack of Carthage in 146 BC.

Quotes

edit- In all human affairs, and especially in those that relate to war, ...leave always some room to fortune, and to accidents which cannot be foreseen.

- The General History, Book II, Ch. 4 (trans. by Hampton)

- It is a course which perhaps would not have been necessary had it been possible to form a state composed of wise men, but as every multitude is fickle, full of lawless desires, unreasoned passion, and violent anger, the multitude must be held in by invisible terrors and suchlike pageantry. For this reason I think, not that the ancients acted rashly and at haphazard in introducing among the people notions concerning the gods and beliefs in the terrors of hell, but that the moderns are most rash and foolish in banishing such beliefs.

- This is a sworn treaty made between us, Hannibal … and Xenophanes the Athenian … in the presence of all the gods who possess Macedonia and the rest of Greece.

- Histories, VII, 9:4 (Loeb, W.R. Paton)

- How highly should we honor the Macedonians, who for the greater part of their lives never cease from fighting with the barbarians for the sake of the security of Greece? For who is not aware that Greece would have constantly stood in the greater danger, had we not been fenced by the Macedonians and the honorable ambition of their kings?

- Histories, IX, 35:2 (Loeb)

- In the past you rivalled the Achaians and the Macedonians, peoples of your own race, and Philip, their commander, for the hegemony and glory, but now that the freedom of the Hellenes is at stake at a war against an alien people (Romans), ...And does it worth to ally with the barbarians, to take the field with them against the Epeirotans, the Achaians, the Akarnanians, the Boiotians, the Thessalians, in fact with almost all the Hellenes with the exception of the Aitolians who are a wicked nation... ...So Lakedaimonians it is good to remember your ancestors,... be afraid of the Romans... and do ally yourselves with the Achaians and Macedonians. But if some the most powerful citizens are opposed to this policy at least stay neutral and do not side with the unjust.

- Histories, IX, 37:7-39:7 (Loeb)

- Had previous chroniclers neglected to speak in praise of History in general, it might perhaps have been necessary for me to recommend everyone to choose for study and welcome such treatises as the present, since men have no more ready corrective of conduct than knowledge of the past. But all historians, one may say without exception, and in no half-hearted manner, but making this the beginning and end of their labour, have impressed on us that the soundest education and training for a life of active politics is the study of History, and that surest and indeed the only method of learning how to bear bravely the vicissitudes of fortune, is to recall the calamities of others. Evidently therefore no one, and least of all myself, would think it his duty at this day to repeat what has been so well and so often said. For the very element of unexpectedness in the events I have chosen as my theme will be sufficient to challenge and incite everyone, young and old alike, to peruse my systematic history. For who is so worthless or indolent as not to wish to know by what means and under what system of polity the Romans in less than fifty-three years have succeeded in subjecting nearly the whole inhabited world to their sole government — a thing unique in history? Or who again is there so passionately devoted to other spectacles or studies as to regard anything as of greater moment than the acquisition of this knowledge?

- How striking and grand is the spectacle presented by the period with which I purpose to deal, will be most clearly apparent if we set beside and compare with the Roman dominion the most famous empires of the past, those which have formed the chief theme of historians. Those worthy of being thus set beside it and compared are these. The Persians for a certain period possessed a great rule and dominion, but so often as they ventured to overstep the boundaries of Asia they imperilled not only the security of this empire, but their own existence. The Lacedaemonians, after having for many years disputed the hegemony of Greece, at length attained it but to hold it uncontested for scarce twelve years. The Macedonian rule in Europe extended but from the Adriatic region to the Danube, which would appear a quite insignificant portion of the continent. Subsequently, by overthrowing the Persian empire they became supreme in Asia also. But though their empire was now regarded as the greatest geographically and politically that had ever existed, they left the larger part of the inhabited world as yet outside it. For they never even made a single attempt to dispute possession of Sicily, Sardinia, or Libya, and the most warlike nations of Western Europe were, to speak the simple truth, unknown to them. But the Romans have subjected to their rule not portions, but nearly the whole of the world and possess an empire which is not only immeasurably greater than any which preceded it, but need not fear rivalry in the future. In the course of this work it will become more clearly intelligible by what steps this power was acquired, and it will also be seen how many and how great advantages accrue to the student from the systematic treatment of history.

- The date from which I propose to begin my history is the 140th Olympiad [220 - 216 B.C.], and the events are the following: (1) in Greece the so‑called Social War, the first waged against the Aetolians by the Achaeans in league with and under the leadership of Philip of Macedon, the son of Demetrius and father of Perseus, (2) in Asia the war for Coele-Syria between Antiochus and Ptolemy Philopator, (3) in Italy, Libya, and the adjacent regions, the war between Rome and Carthage, usually known as the Hannibalic War. These events immediately succeed those related at the end of the work of Aratus of Sicyon. Previously the doings of the world had been, so to say, dispersed, as they were held together by no unity of initiative, results, or locality; but ever since this date history has been an organic whole, and the affairs of Italy and Libya have been interlinked with those of Greece and Asia, all leading up to one end. And this is my reason for beginning their systematic history from that date.

- For what gives my work its peculiar quality, and what is most remarkable in the present age, is this. Fortune has guided almost all the affairs of the world in one direction and has forced them to incline towards one and the same end; a historian should likewise bring before his readers under one synoptical view the operations by which she has accomplished her general purpose.

- I observe that while several modern writers deal with particular wars and certain matters connected with them, no one, as far as I am aware, has even attempted to inquire critically when and whence the general and comprehensive scheme of events originated and how it led up to the end. I therefore thought it quite necessary not to leave unnoticed or allow to pass into oblivion this the finest and most beneficent of the performances of Fortune. For though she is ever producing something new and ever playing a part in the lives of men, she has not in a single instance ever accomplished such a work, ever achieved such a triumph, as in our own times. We can no more hope to perceive this from histories dealing with particular events than to get at once a notion of the form of the whole world, its disposition and order, by visiting, each in turn, the most famous cities, or indeed by looking at separate plans of each: a result by no means likely. He indeed who believes that by studying isolated histories he can acquire a fairly just view of history as a whole, is, as it seems to me, much in the case of one, who, after having looked at the dissevered limbs of an animal once alive and beautiful, fancies he has been as good as an eyewitness of the creature itself in all its action and grace.

- We can get some idea of a whole from a part, but never knowledge or exact opinion. Special histories therefore contribute very little to the knowledge of the whole and conviction of its truth. It is only indeed by study of the interconnexion of all the particulars, their resemblances and differences, that we are enabled at least to make a general survey, and thus derive both benefit and pleasure from history.

- All things are subject to decay and change.

- The General History of Polybius as translated by James Hampton' (1762), Vol. II, pp. 177-178

- When a state after having passed with safety through many and great dangers arrives at the higher degree of power, and possesses an entire and undisputed sovereignty, it is manifest that the long continuance of prosperity must give birth to costly and luxurious manners, and that the minds of men will be heated with ambitious contests, and become too eager and aspiring in the pursuit of dignities. And as those evils are continually increased, the desire of power and rule, along with the imagined ignominy of remaining in a subject state, will first begin to work the ruin of the republic; arroagance and luxury will afterwards advance it; and in the end the change will be completed by the people; when the avarice of some is found to injure and oppress them, and the ambition of others swells their vanity, and poisons them with flattering hopes. For then, being inflamed with rage, and following only the dictates of their passions, they no longer will submit to any control, or be contented with an equal share of the administration, in conjunction with their rules; but will draw to themselves the entire sovereignty and supreme direction of all affairs. When this is done, the government will assume indeed the fairest of a ll names, that of a free and popular state; but will in truth be the greatest of all evils, the government of the multitude.

- The General History of Polybius as translated by James Hampton' (1762), Vol. II, pp. 177-178

- The only method of learning to bear with dignity the vicissitudes of fortune is to recall the catastrophes of others.

- Polybius. The Histories of Polybius, trans. Evelyn S. Shuckburgh. London, New York: Macmillan and Co., 1889. Book I, Chapter 1

Quotes about Polybius

edit- [Polybius is] a great historian, a very great orator, and best of all as a philosopher.

- Lodovico Domenichi, dedication to Polibio Historico Greco (Venice, 1545), quoted in Peter Burke, 'A Survey of the Popularity of Ancient Historians, 1450–1700', History and Theory, Vol. 5, No. 2 (1966), p. 144

- Whensoever he gives us the account of any considerable action, he never fails to tell us why it succeeded, or for what reason it miscarried; together with all the antecedent causes of its undertaking, and the manner of its performance; all which he accurately explains.

- John Dryden, The Character of Polybius (1692), quoted in The Works of John Dryden, Vol. XVIII (1808), p. 44

- [Polybius] digresses, interrupts himself, is diffuse, and often explicitly teaches rather than tells a story. But his lessons are always worthwhile ones.

- Justus Lipsius, Notes (1589), quoted in Peter Burke, 'A Survey of the Popularity of Ancient Historians, 1450–1700', History and Theory, Vol. 5, No. 2 (1966), p. 145

- Polybius mentions Plato’s theory, but his picture of the transformation of good constitutions into bad is more Aristotelian: the good forms—monarchy, aristocracy, politeia—turn into their bad opposites—tyranny, oligarchy, mob rule. Polybius had no interest in the search for a philosopher-king and was not concerned to explain why perfection could not last forever. Utopia was uninteresting; since it never existed, it could teach no lessons. Polybius knew that the works of man are imperfect; sooner or later even the Roman Empire will decay, probably sooner rather than later. The destruction of Carthage brought tears to Scipio’s eyes, even as he ordered its completion; and Virgil’s Aeneid is surely a reflection on the theme of Troy, Carthage—and Rome? The question was how the Romans had thus far escaped what seemed to be their inevitable fate. They had begun with a botched constitution: they established elected kings with few checks. Nonetheless, their ancient kings had not become tyrants; they had been expelled. Even then a mixed constitution was not instituted by a Roman Lycurgus, and all of a piece, but evolved by trial and error. How had the Romans done it? Prompted by Livy, who himself was much in debt to Polybius, Machiavelli asked just that question.10 The question remains important even after we reject cyclical (indeed any or all) theories of history; states can recover from unpromising beginnings, and it is worth knowing how they do it. It was obvious to Polybius that Rome had done it; his problem was to square the facts with the theory.

- Alan Ryan, On Politics: A History of Political Thought: From Herodotus to the Present (2012), Ch. 4 : Roman Insights: Polybius and Cicero

- Polybius's picture of the motors of political change is persuasive if not taken rigidly, and it provides a rationalization of Roman history: leaders who rise by their talents will (at least initially) live like their fellows and arouse no hostility, while those who inherit a throne will separate themselves from everyone else and arouse envy. They will be opposed by men of the upper class affronted by the insolence of their king—or kings, since Polybius knew that Sparta and Rome had been ruled by a collective monarchy. When they are overthrown, their aristocratic supplanters will rule in their stead. That aristocracies degenerate into oligarchies is the most common complaint against aristocratic governments, and often leveled at their modern descendants, the elected aristocrats who occupy the seats of power in the modern democratic world. Readers will find less persuasive Polybius’s claim that when an oligarchy is overturned, democracy invariably follows. He says that the memory of the tyranny of kings will be too fresh in everyone’s mind for there to be a reversal of the cycle from oligarchy to monarchy, but this is empirically unconvincing; it turns the unusual experience of Athens and Rome into a principle. We are all too familiar with situations in which a disgusted public turns to a dictator, though it has to be said in Polybius’s favor that “oligarchy-democracy-dictatorship” is perhaps the most common cycle of all.

- Alan Ryan, On Politics: A History of Political Thought: From Herodotus to the Present (2012), Ch. 4 : Roman Insights: Polybius and Cicero

- When he talks of war, which is the favourite subject and darling of history, how like a general and perfect master in that trade does he acquit himself!

- Sir Henry Sheeres (d.1710), preface to The History of Polybius (London, 1693), quoted in Peter Burke, 'A Survey of the Popularity of Ancient Historians, 1450–1700', History and Theory, Vol. 5, No. 2 (1966), p. 145

- [Polybius] is not content to narrate; he also instructs, fulfilling two functions, those of the historian and the philosopher.

- Gerardus Vossius, Greek Historians (1650), quoted in Peter Burke, 'A Survey of the Popularity of Ancient Historians, 1450–1700', History and Theory, Vol. 5, No. 2 (1966), p. 145

External links

edit- Short introduction to the life and work of Polybius

- The Histories or The Rise of the Roman Empire by Polybius: