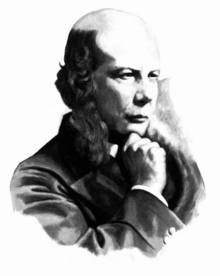

Henry James Sumner Maine

British jurist and historian (1822–1888)

Sir Henry James Sumner Maine (15 August 1822 – 3 February 1888) was a British comparative jurist, historian and political proto-progressive nonetheless famous for his varied objections to Whig history.

Quotes

edit- The movement of the progressive societies has hitherto been a movement from Status to Contract.

- Ancient Law, Its Connection with the Early History of Society, and Its Relation to Modern Ideas (1 ed.). London: John Murray (1861). p. 170

- The family was based, not upon actual relationship, but upon power, and the husband acquired over his wife the same despotic power which the father had over his children.

- We cannot give a reason, other than mere chance, why power over a wife should have retained the name of manus, why power over a child should have obtained another name, potestas, why power over slaves and inanimate property should in later times be called dominium. But, although the transformation of meanings be capricious, the process of specialisation is a permanent phenomenon, in the highest degree important and worthy of observation.

- So great is the ascendancy of the Law of Actions in the infancy of Courts of Justice, that substantive law has at first the look of being gradually secreted in the interstices of procedure; and the early lawyer can only see the law through the envelope of its technical forms.

- ‘Dissertations on Early Law and Custom’ (1883) ch. 11

- Nobody is at liberty to attack several property and to say at the same time that he values civilisation. The history of the two cannot be disentangled. Civilisation is nothing more than a name for the old order of the Aryan world, dissolved but perpetually re-constituting itself under a vast variety of solvent influences, of which infinitely the most powerful have been those which have, slowly, and in some parts of the world much less perfectly than others, substituted several property for collective ownership.

- Village-Communities in the East and West (1876 ed.), p. 230

- Except the blind forces of Nature, nothing moves in this world which is not Greek in its origin.

- ‘Village Communities’ (3rd ed., 1876) p. 238

- The new theory of Language has unquestionably produced a new theory of Race . . . If you examine the bases proposed for common nationality before the new knowledge growing out of the study of Sanskrit had popularized in Europe, you will find them extremely unlike those which are now advocated and even passionately advocated in part of the Continent.

- Cited from: Malhotra, R., Nīlakantan, A. (Princeton, N.J.). (2011). Breaking India: Western interventions in Dravidian and Dalit faultlines

- With an Introduction by George W. Carey (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1976). (Original work published 1885)

- Here then we have one great inherent infirmity of popular governments, an infirmity deducible from the principle of Hobbes, that liberty is power cut into fragments. Popular governments can only be worked by a process which incidentally entails the further subdivision of the morsels of political power; and thus the tendency of these governments, as they widen their electoral basis, is towards a dead level of commonplace opinion, which they are forced to adopt as the standard of legislation and policy. The evils likely to be thus produced are rather those vulgarly associated with Ultra-Conservatism than those of Ultra-Radicalism.

- pp. 62-63

- So far indeed as the human race has experience, it is not by political societies in any way resembling those now called democracies that human improvement has been carried on. History, said Strauss - and, considering his actual part in life, this is perhaps the last opinion which might have been expected from him - History is a sound aristocrat. There may be oligarchies close enough and jealous enough to stifle thought as completely as an Oriental despot who is at the same time the pontiff of a religion; but the progress of mankind has hitherto been effected by the rise and fall of aristocracies, by the formation of one aristocracy within another, or by the succession of one aristocracy to another. There have been so-called democracies, which have rendered services beyond price to civilisation, but they were only peculiar forms of aristocracy.

The short-lived Athenian democracy, under whose shelter art, science, and philosophy shot so wonderfully upwards, was only an aristocracy which rose on the ruins of one much narrower. The splendour which attracted the original genius of the then civilised world to Athens was provided by the severe taxation of a thousand subject cities; and the skilled labourers who worked under Phidias, and who built the Parthenon, were slaves.- p. 63

- [T]he Constitutions and the legal systems of the several North American States, and of the United States, would be wholly unintelligible to anybody who did not know that the ancestors of the Anglo-Americans had once lived under a King, himself the representative of older Kings infinitely more autocratic, and who had not observed that throughout these bodies of law and plans of government the People had simply been put into the King's seat, occasionally filling it with some awkwardness. The advanced Radical politician of our day would seem to have an impression that Democracy differs from Monarchy in essence. There can be no grosser mistake than this, and none more fertile of further delusions.

- p. 81

- [I]n the very first place, Democracy, like Monarchy, like Aristocracy, like any other government, must preserve the national existence. The first necessity of a State is that it should be durable. Among mankind regarded as assemblages of individuals, the gods are said to love those who die young; but nobody has ventured to make such an assertion of States. The prayers of nations to Heaven have been, from the earliest ages, for long national life, life from generation to generation, life prolonged far beyond that of children's children, life like that of the everlasting hills.

...Next perhaps to the paramount duty of maintaining national existence, comes the obligation incumbent on Democracies, as on all governments, of securing the national greatness and dignity. Loss of territory, loss of authority, loss of general respect, loss of self-respect, may be unavoidable evils, but they are terrible evils.- pp. 81-82

- [T]he extreme forms of government, Monarchy and Democracy, have a peculiarity which is absent from the more tempered political systems founded on compromise, Constitutional Kingship and Aristocracy. When they are first established in absolute completeness, they are highly destructive. There is a general, sometimes chaotic, upheaval, while the nouvelles couches are settling into their place in the transformed commonwealth.

- pp. 85-86

- There is no belief less warranted by actual experience, than that a democratic republic is, after the first and in the long-run, given to reforming legislation. As is well known to scholars, the ancient republics hardly legislated at all; their democratic energy was expended upon war, diplomacy, and justice; but they put nearly insuperable obstacles in the way of a change of law. The Americans of the Umted States have hedged themselves round in exactly the same way.

- p. 86

- The prejudices of the people are far stronger than those of the privileged classes; they are far more vulgar; and they are far more dangerous, because they are apt to run counter to scientific conclusions.

- p. 87

- The delusion that Democracy, when it has once had all things put under its feet, is a progressive form of government, lies deep in the convictions of a particular political school, but there can be no delusion grosser.

- p. 111

- The natural condition of mankind (if that word "natural" is used) is not the progressive condition. It is a condition not of changeableness but of unchangeableness. The immobility of society is the rule; its mobility is the exception. The toleration of change and the belief in its advantages are still confined to the smallest portion of the human race, and even with that portion they are extremely modern.

- p. 175

- Whether - and this is the last objection - the age of aristocracies be over, I cannot take upon myself to say. I have sometimes thought it one of the chief drawbacks on modern democracy that, while it gives birth to despotism with the greatest facility, it does not seem to be capable of producing aristocracy, though from that form of political and social ascendency all improvement has hitherto sprung.

- p. 190

Quotes about Maine

edit- We want to help to better the conditions for our own people. We want to see our people raised, not into a society of State ownership, but into a society in which, increasingly, the individual may become an owner. There is a very famous sentence of Sir Henry Maine's, in which he said that the progress of our civilisation had been of recent centuries a progress on the part of mankind from status to contract. Socialism would bring him back from contract to status.

- Stanley Baldwin, speech to the Junior Imperial League (3 May 1924), quoted in On England, and Other Addresses (1926), p. 225

- Intellectually he was a giant; I have hardly ever known anyone who gave me such an impression of the power and grasp of his mind. Like Mr. Gladstone, he would sometimes, when he was talking to me in my room, get interested in his subject, and, with great emphasis, and in an unnecessarily loud voice, deliver a speech which, if it had been taken down, would have been an appreciable addition to the sum of human thought. In Council he rarely spoke, but when he did so, always with the same thunderous voice and commanding air, he invariably convinced everybody and carried his point. His knowledge, his sagacity, his insight were wonderful, and they were by no means confined to questions of law.

- Lord Kilbracken, Reminiscences of Lord Kilbracken (1931), pp. 161-162

- Maine has always spoken to me in strong dislike of the acts of Modern Liberals & I believe he was to have stood as a moderate Conservative at Cambridge. I take him to be of the same politics as many of the Liberals of thirty years ago, who are now Conservative. I believe he writes for the St James Gazette & he has written four articles against Democracy in the Quarterly which have attracted a great deal of attention.

- Lord Salisbury to R. A. Cross (2 July 1885), quoted in Michael Bentley, Lord Salisbury's World: Conservative Environments in Late-Victorian Britain (2001), p. 130. The four articles were published as Popular Government (1885)

See also

editExternal links

editGreg Conti, The Roots of Right-Wing Progressivism