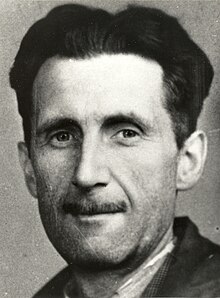

George Orwell

British writer and journalist (1903–1950)

(Redirected from Orwell)

George Orwell (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) was the pen name of British novelist, essayist, and journalist Eric Arthur Blair, whose work is characterised by lucid prose, awareness of social injustice, opposition to totalitarianism, and strong support of democratic socialism.

- See also:

Quotes

edit- Spending the night out of doors has nothing attractive about it in London, especially for a poor, ragged, undernourished wretch. Moreover sleeping in the open is only allowed in one thoroughfare in London. If the policeman on his beat finds you asleep, it is his duty to wake you up. That is because it has been found that a sleeping man succumbs to the cold more easily than a man who is awake, and England could not let one of her sons die in the street. So you are at liberty to spend the night in the street, providing it is a sleepless night. But there is one road where the homeless are allowed to sleep. Strangely, it is the Thames Embankment, not far from the Houses of Parliament. We advise all those visitors to England who would like to see the reverse side of our apparent prosperity to go and look at those who habitually sleep on the Embankment, with their filthy tattered clothes, their bodies wasted by disease, a living reprimand to the Parliament in whose shadow they lie.

- "Beggars in London", in Le Progrès Civique (12 January 1929), translated into English by Janet Percival and Ian Willison

- This means no more than vae victis - woe to the creed that is not backed by machine-guns!

- Review of The Two Carlyles by Osbert Burdett, in The Adelphi (March 1931)

- To the well-fed it seems cowardly to complain of tight boots, because the well-fed live in a different world-a world where, if your boots are tight, you can change them; their minds are not warped by petty discomfort. But below a certain income the petty crowds the large out of existence; one's preoccupation is not with art or religion, but with bad food, hard beds, drudgery and the sack. Serenity is impossible to a poor man in a cold country and even his active thoughts will go in more or less sterile complaint.

- Review of Hunger and Love by Lionel Britton, in The Adelphi (April 1931)

- And once, in spite of the men who gripped him by each shoulder, he stepped slightly aside to avoid a puddle on the path. It is curious, but till that moment I had never realised what it means to destroy a healthy, conscious man. When I saw the prisoner step aside to avoid the puddle, I saw the mystery, the unspeakable wrongness, of cutting a life short when it is in full tide. This man was not dying, he was alive just as we were alive. All the organs of his body were working – bowels digesting food, skin renewing itself, nails growing, tissues forming – all toiling away in solemn foolery. His nails would still be growing when he stood on the drop, when he was falling through the air with a tenth of a second to live. His eyes saw the yellow gravel and the grey walls, and his brain still remembered, foresaw, reasoned – reasoned even about puddles. He and we were a party of men walking together, seeing, hearing, feeling, understanding the same world; and in two minutes, with a sudden snap, one of us would be gone – one mind less, one world less.

- "A Hanging", in The Adelphi (August 1931)

- In England, a century of strong government has developed what O. Henry called the stern and rugged fear of the police to a point where any public protest seems an indecency. But in France everyone can remember a certain amount of civil disturbance, and even the workmen in the bistros talk of la revolution — meaning the next revolution, not the last one. The highly socialised modern mind, which makes a kind of composite god out of the rich, the government, the police and the larger newspapers, has not been developed — at least not yet.

- Review of The Civilization of France by Ernst Robert Curtius; translated by Olive Wyon, in The Adelphi (May 1932)

- As to a pseudonym, a name I always use when tramping etc is P. S. Burton, but if you don't think this sounds a probable kind of name, what about Kenneth Miles, George Orwell, H. Lewis Allways. I rather favour George Orwell.

- Letter to Leonard Moore (19 November 1932)

- The Collected Essays, Journalism & Letters, George Orwell: An Age Like This, 1920–1940, Editors: Sonia Orwell, Ian Angus. p. 106.

- Man is not a Yahoo, but he is rather like a Yahoo and needs to be reminded of it from time to time.

- Review of Tropic of Cancer, in New English Weekly (14 November 1935)

- Think of life as it really is, think of the details of life; and then think that there is no meaning in it, no purpose, no goal except the grave. Surely only fools or self-deceivers, or those whose lives are exceptionally fortunate, can face that thought without flinching?

- A Clergyman's Daughter, Ch. 2 (1935)

- It is a mysterious thing, the loss of faith-as mysterious as faith itself. Like faith, it is ultimately not rooted in logic; it is a change in the climate of the mind.

- A Clergyman's Daughter, Ch. 5

- There is a geographical element in all belief-saying what seem profound truths in India have a way of seeming enormous platitudes in England, and vice versa. Perhaps the fundamental difference is that beneath a tropical sun individuality seems less distinct and the loss of it less important.

- Review of Indian Mosaic by Mark Channing, in The Listener (15 July 1936)

- I am struck again by the fact that as soon as a working man gets an official post in the Trade Union or goes into Labour politics, he becomes middle-class whether he will or no. ie. by fighting against the bourgeoisie he becomes a bourgeois. The fact is that you cannot help living in the manner appropriate and developing the ideology appropriate to your income.

- The Road to Wigan Pier Diary 6-10 February (1936)

- For the dreadful thing about the kind of brutalities here described, is that they are quite unavoidable. When a subject population rises in revolt you have got to suppress it, and you can only do so by methods which make nonsense of any claim for the superiority of western civilisation. In order to rule over barbarians, you have got to become a barbarian yourself.

- Review of Zest for Life by Johann Wöller, in Time and Tide (17 October 1936)

- In a town like London there are always plenty of not quite certifiable lunatics walking the streets, and they tend to gravitate towards bookshops, because a bookshop is one of the few places where you can hang about for a long time without spending any money.

- “Bookshop Memories” in Fortnightly (November 1936)

- In addition to this there is the horrible — the really disquieting — prevalence of cranks wherever Socialists are gathered together. One sometimes gets the impression that the mere words 'Socialism' and 'Communism' draw towards them with magnetic force every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, 'Nature Cure' quack, pacifist, and feminist in England.

- The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) - Full text online

- When I left Barcelona in late June the jails were bulging; indeed, the regular jails had long since overflowed and the prisoners were being huddled into empty shops and any other temporary dump that could be found for them. But the point to notice is that the people who are in prison now are not Fascists but revolutionaries; they are there not because their opinions are too much to the Right, but because they are too much to the Left. And the people responsible for putting them there are those dreadful revolutionaries at whose very name Garvin quakes in his galoshes – the Communists.

- “Spilling the Spanish Beans,” New English Weekly, (July 29 and Sept. 2, 1937)

- And so the game continues. The logical end is a régime in which every opposition party and newspaper is suppressed and every dissentient of any importance is in jail. Of course, such a régime will be Fascism. It will not be the same as the Fascism Franco would impose, it will even be better than Franco’s Fascism to the extent of being worth fighting for, but it will be Fascism. Only, being operated by Communists and Liberals, it will be called something different.

- “Spilling the Spanish Beans,” New English Weekly, (July 29 and Sept. 2, 1937)

- Later, as power slipped from the hands of the Anarchists into the hands of the Communists and right-wing Socialists, the Government was able to reassert itself, the bourgeoisie came out of hiding and the old division of society into rich and poor reappeared, not much modified. Henceforward every move, except a few dictated by military emergency, was directed towards undoing the work of the first few months of revolution.

- “Spilling the Spanish Beans,” New English Weekly, (July 29 and Sept. 2, 1937)

- War against a foreign country only happens when the moneyed classes think they are going to profit from it.

- Every war, when it comes, or before it comes, is represented not as a war but as an act of self-defence against a homicidal maniac.

- The essential job is to get people to recognise war propaganda when they see it, especially when it is disguised as peace propaganda.

- Review of The Men I Killed by Brigadier-General F. P. Crozier, CB, CMG, DSO, in New Statesman and Nation (28 August 1937)

- You cannot be objective about an aerial torpedo. And the horror we feel of these things has led to this conclusion: if someone drops a bomb on your mother, go and drop two bombs on his mother. The only apparent alternatives are to smash dwelling houses to powder, blow out human entrails and burn holes in children with thermite, or to be enslaved by people who are more ready to do these things than you are yourself; as yet no one has suggested a practicable way out.

- Review of Spanish Testament by Arthur Koestler, February 1938

- One is almost driven to the cynical conclusion that men are only decent when they are powerless.

- Review of The Freedom of the Streets by Jack Common, June 1938, pp. 335-6

- If there are certain pages of Mr Bertrand Russell's book, Power, which seem rather empty, that is merely to say that we have now sunk to a depth at which the restatement of the obvious is the first duty of intelligent men.

- Review of Power: A New Social Analysis by Bertrand Russell in The Adelphi (January 1939)

- Paraphrased variant: Sometimes the first duty of intelligent men is the restatement of the obvious.

- It is not merely that at present the rule of naked force obtains almost everywhere. Probably that has always been the case. Where this age differs from those immediately preceding it is that a liberal intelligentsia is lacking. Bully-worship, under various disguises, has become a universal religion, and such truisms as that a machine-gun is still a machine-gun even when a "good" man is squeezing the trigger — and that in effect is what Mr Russell is saying — have turned into heresies which it is actually becoming dangerous to utter.

- Review of Power: A New Social Analysis by Bertrand Russell in The Adelphi (January 1939)

- It is quite possible that we are descending into an age in which two plus two will make five when the Leader says so.

- Review of Power: A New Social Analysis by Bertrand Russell in The Adelphi (January 1939)

- Acceptance of the Catholic position implies a certain willingness to see the present injustices of society continue... Individual salvation implies liberty, which is always extended by Catholic writers to include the right to private property. But in the stage of industrial development which we have now reached, the right to private property means the right to exploit and torture millions of one's fellow creatures. The Socialist would argue, therefore, that one can only defend property if one is more or less indifferent to economic justice.

- Review of Communism and Man by F. J. Sheed in Peace News (27 January 1939)

- Has it ever struck you that there's a thin man inside every fat man, just as they say there's a statue inside every block of stone?

- Coming Up for Air, Part 1, Ch. 3

- The past is a curious thing. It's with you all the time. I suppose an hour never passes without your thinking of things that happened ten or twenty years ago, and yet most of the time it's got no reality, it's just a set of facts that you've learned, like a lot of stuff in a history book. Then some chance sight or sound or smell, especially smell, sets you going, and the past doesn't merely come back to you, you're actually in the past.

- Coming Up for Air, Part I, Ch. 4 (1939)

- Perhaps a man really dies when his brain stops, when he loses the power to take in a new idea.

- Coming Up for Air, Part 3, Ch. 1

- It is not possible for any thinking person to live in such a society as our own without wanting to change it.

- "Why I Joined the Independent Labour Party", New Leader (24 June 1939)

- Adults are only less superstitious than children in proportion as they have more power over their environment. In predicaments where everyone is powerless (eg war, gambling) everyone is superstitious

- New Words (1940)

- The Collected Essays, Journalism & Letters, George Orwell: My Country Right or Left, 1940–1943, Editors: Sonia Orwell, Ian Angus. p. 9 (footnote)

- Mr Auden's brand of amoralism is only possible if you are the kind of person who is always somewhere else when the trigger is pulled. So much of left-wing thought is a kind of playing with fire by people who don't even know that fire is hot.

- Inside the Whale (1940) [1]

- [Hitler] has grasped the falsity of the hedonistic attitude to life. Nearly all western thought since the last war, certainly all "progressive" thought, has assumed tacitly that human beings desire nothing beyond ease, security, and avoidance of pain. In such a view of life there is no room, for instance, for patriotism and the military virtues. The Socialist who finds his children playing with soldiers is usually upset, but he is never able to think of a substitute for the tin soldiers; tin pacifists somehow won't do. Hitler, because in his own joyless mind he feels it with exceptional strength, knows that human beings don’t only want comfort, safety, short working-hours, hygiene, birth-control and, in general, common sense; they also, at least intermittently, want struggle and self-sacrifice, not to mention drums, flags and loyalty-parades. However they may be as economic theories, Fascism and Nazism are psychologically far sounder than any hedonistic conception of life. The same is probably true of Stalin's militarised version of Socialism. All three of the great dictators have enhanced their power by imposing intolerable burdens on their peoples. Whereas Socialism, and even capitalism in a grudging way, have said to people "I offer you a good time," Hitler has said to them "I offer you struggle, danger and death," and as a result a whole nation flings itself at his feet.

- From a review of Adolf Hitler's Mein Kampf, New English Weekly (21 March 1940)

- [...]I should say that it is a good rule of thumb never to mention religion if you can possibly avoid it.

- Letter to Humphry House (11 April 1940). The Collected Essays, Journalism & Letters, George Orwell: An Age Like This, 1920–1940, Editors: Sonia Orwell, Ian Angus. p. 530.

- [T]here is something wrong with a regime that requires a pyramid of corpses every few years.

- Letter to Humphry House, (11 April 1940). The Collected Essays, Journalism, & Letters, George Orwell: An age like this, 1920–1940, Editors: Sonia Orwell, Ian Angus. p. 532.

- It is all very well to be "advanced" and "enlightened," to snigger at Colonel Blimp and proclaim your emancipation from all traditional loyalties, but a time comes when the sand of the desert is sodden red and what have I done for thee, England, my England? As I was brought up in this tradition myself I can recognise it under strange disguises, and also sympathise with it, for even at its stupidest and most sentimental it is a comelier thing than the shallow self-righteousness of the left-wing intelligentsia.

- From a review of Malcolm Muggeridge's The Thirties, in New English Weekly (25 April 1940)

- National Socialism is a form of Socialism, is emphatically revolutionary, does crush the property owner as surely as it crushes the worker. The two regimes, having started from opposite ends, are rapidly evolving towards the same system—a form of oligarchical collectivism. . . . It is Germany that is moving towards Russia, rather than the other way about. It is therefore nonsense to talk about Germany ‘going Bolshevik’ if Hitler falls. Germany is going Bolshevik because of Hitler and not in spite of him.

- Review of The Totalitarian Enemy by F. Borkenau, Time and Tide (4 May 1940). Orwell: My Country Right or Left - 1940 to 1943, Vol. 2, Essays, Journalism & Letters, Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus, edit., Boston, MA, Nonpareil Books (2000), p. 25.

- From the first the aim of the Nazis was to turn Germany into a war-machine, and to subordinate everything else to that purpose. But a country, and especially a poor country, which is waging or preparing for ‘total’ war must be in some sense socialistic. When the State has taken complete control of industry, when the so-called capitalist is reduced to the status of a manager, when consumption goods are so scare and strictly rationed that you cannot spend a big income even if you earn one, then the essential structure of Socialism already exists, plus the comfortless equality of war-Communism.

- Review of The Totalitarian Enemy by F. Borkenau, Time and Tide (4 May 1940). Orwell: My Country Right or Left - 1940 to 1943, Vol. 2, Essays, Journalism & Letters, Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus, edit., Boston, MA, Nonpareil Books (2000), p. 25.

- We are in a strange period of history in which a revolutionary has to be a patriot and a patriot has to be a revolutionary.

- Letter to The Tribune (20 December 1940), later published in A Patriot After All, 1940-1941 (1999)

- Even as it stands, the Home Guard could only exist in a country where men feel themselves free. The totalitarian states can do great things, but there is one thing they cannot do: they cannot give the factory-worker a rifle and tell him to take it home and keep it in his bedroom. THAT RIFLE HANGING ON THE WALL OF THE WORKING-CLASS FLAT OR LABOURER'S COTTAGE, IS THE SYMBOL OF DEMOCRACY. IT IS OUR JOB TO SEE THAT IT STAYS THERE.

- "Don't Let Colonel Blimp Ruin the Home Guard" article for the Evening Standard, 8 January 1941

- Society has always to demand a little more from human beings than it will get in practice.

- "The Art of Donald McGill" (1941)

- The peculiarity of the totalitarian state is that though it controls thought, it does not fix it. It sets up unquestionable dogmas, and it alters them from day to day. It needs the dogmas, because it needs absolute obedience from its subjects, but cannot avoid the changes, which are dictated by the needs of power politics. It declared itself infallible, and at the same time it attacks the very concept of objective truth.

- “Literature and Totalitarianism”, a broadcast talk in the BBC Overseas Service; printed in The Listener (19 June 1941)

- Civilisation rests ultimately on coercion. What holds society together is not the policeman but the goodwill of common men, and yet that goodwill is powerless unless the policeman is there to back it up. Any government which refused to use violence in its own defence would cease almost immediately to exist, because it would be overthrown by any body of men, or even any individual, that was less scrupulous.

- "No, Not One," The Adelphi (October 1941)

- Since pacifists have more freedom of action in countries where traces of democracy survive, pacifism can act more effectively against democracy than for it. Objectively the pacifist is pro-Nazi.

- "No, Not One," The Adelphi (October 1941)

- See his later thoughts on this statement below from "As I Please," Tribune (8 December 1944)

- Pacifism is only a considerable force in places where people feel themselves very safe, chiefly maritime states. [...] The notion that you can somehow defeat violence by submitting to it is simply a flight from fact. As I have said, it is only possible to people who have money and guns between themselves and reality.

- "No, Not One," The Adelphi (October 1941)

- The choice before human beings, is not, as a rule, between good and evil but between two evils. You can let the Nazis rule the world: that is evil; or you can overthrow them by war, which is also evil. There is no other choice before you, and whichever you choose you will not come out with clean hands.

- I have now been in the BBC about 6 months. Shall remain in it if the political changes I foresee come off, otherwise probably not. Its atmosphere is something halfway between a girls' school and a lunatic asylum, and all we are doing at present is useless, or slightly worse than useless.

- Diary entry (14 March 1942)

- The Collected Essays, Journalism & Letters, George Orwell: My Country Right or Left, 1940–1943, Editors: Sonia Orwell, Ian Angus. p. 411

- In this war we have one weapon which our enemies cannot use against us, and that is the English language. Several other languages are spoken by larger numbers of people, but there is no other that has any claim to be a world-wide lingua franca.

- Review of The Sword and the Sickle by Mulk Raj Anand, Horizon (July 1942)

- Everyone believes in the atrocities of the enemy and disbelieves in those of his own side, without ever bothering to examine the evidence.

- "Looking Back on the Spanish War" (Autumn 1942)

- The Collected Essays, Journalism & Letters, George Orwell: My Country Right or Left, 1940–1943, Editors: Sonia Orwell, Ian Angus. p. 252

- You and I both know that there can be no real solution of the Indian problem which does not also benefit Britain. Either we all live in a decent world, or nobody does. It is so obvious, is it not, that the British worker as well as the Indian peasant stands to gain by the ending of capitalist exploitation, and that Indian independence is a lost cause if the Fascist nations are allowed to dominate the world.

- From a review of Letters on India by Mulk Raj Anand, Tribune (19 March 1943)

- It was thinking of people like him [William Empson] that made me rather angry about what you said of the BBC, though God knows I have the best means of judging what a mixture of whoreshop and lunatic asylum it is for the most part.

- Letter to Alex Comfort (11? July 1943)

- The Collected Essays, Journalism & Letters, George Orwell: My Country Right or Left, 1940–1943, Editors: Sonia Orwell, Ian Angus. p. 305

- Both men were the spiritual children of Voltaire, both had an ironical, sceptical view of life, and a native pessimism overlaid by gaiety; both knew that the existing social order is a swindle and its cherished beliefs mostly delusions.

- On Mark Twain and Anatole France, in "Mark Twain - The Licensed Jester" in Tribune (26 November 1943); reprinted in The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell (1968)

- Nearly all creators of Utopia have resembled the man who has toothache, and therefore thinks happiness consists in not having toothache. They wanted to produce a perfect society by an endless continuation of something that had only been valuable because it was temporary. The wider course would be to say that there are certain lines along which humanity must move, the grand strategy is mapped out, but detailed prophecy is not our business. Whoever tries to imagine perfection simply reveals his own emptiness.

- "Can Socialists Be Happy?", Tribune (20 December 1943). Published under the name ‘John Freeman’.

- The real objective of Socialism is human brotherhood. This is widely felt to be the case, though it is not usually said, or not said loudly enough. Men use up their lives in heart-breaking political struggles, or get themselves killed in civil wars, or tortured in the secret prisons of the Gestapo, not in order to establish some central-heated, air-conditioned, strip-lighted Paradise, but because they want a world in which human beings love one another instead of swindling and murdering one another.

- "Can Socialists Be Happy?", Tribune (20 December 1943).

- From Carlyle onwards, but especially in the last generation, the British intelligentsia have tended to take their ideas from Europe and have been infected by habits of thought that derive ultimately from Machiavelli. All the cults that have been fashionable in the last dozen years, Communism, Fascism, and pacifism, are in the last analysis forms of power worship.

- "The English People" (written Spring 1944, published 1947)[2]

- Mr Noyes remarks at the beginning of his book that one cannot cast out devils with the aid of Beelzebub, but he is also extremely angry because anti-British books can still be published in England and praised in British newspapers. Does it not occur to him that if we stop doing this kind of thing the main difference between ourselves and our enemies would have disappeared?

- Review. The Edge of the Abyss by Alfred Noyes

- Observer, 27 February 1944

- The Collected Essays, Journalism & Letters, George Orwell: As I Please, 1943-1945, Editors: Sonia Orwell, Ian Angus. pp. 100-101.

- Shortly, Professor Hayek's thesis is that Socialism inevitably leads to despotism, and that in Germany the Nazis were able to succeed because the Socialists had already done most of their work for them, especially the intellectual work of weakening the desire for liberty. By bringing the whole of life under the control of the State, Socialism necessarily gives power to an inner ring of bureaucrats, who in almost every case will be men who want power for its own sake and will stick at nothing in order to retain it. Britain, he says, is now going the same road as Germany, with the left-wing intelligentsia in the van and the Tory Party a good second. The only salvation lies in returning to an unplanned economy, free competition, and emphasis on liberty rather than on security. In the negative part of Professor Hayek's thesis there is a great deal of truth. It cannot be said too often — at any rate, it is not being said nearly often enough — that collectivism is not inherently democratic, but, on the contrary, gives to a tyrannical minority such powers as the Spanish Inquisitors never dreamed of.

- “Review of the Road to Serfdom by F.A. Hayek, etc,” The Observer (9 April 1944) and in As I please, 1943–1945: The Collected Essays, Journalism & Letters, Vol. 30.

- Between them these two books sum up our present predicament. Capitalism leads to dole queues, the scramble for markets, and war. Collectivism leads to concentration camps, leader worship, and war. There is no way out of this unless a planned economy can somehow be combined with the freedom of the intellect, which can only happen if the concept of right and wrong is restored to politics.

- Review of The Road to Serfdom by F.A. Hayek and The Mirror of the Past by K. Zilliacus, reviewed in The Observer (9 April 1944).

- Hitler, no doubt, will soon disappear, but only at the expense of strengthening (a) Stalin, (b) the Anglo-American millionaires and (c) all sorts of petty fuhrers of the type of de Gaulle. All the national movements everywhere, even those that originate in resistance to German domination, seem to take non-democratic forms, to group themselves round some superhuman fuhrer (Hitler, Stalin, Salazar, Franco, Gandhi, De Valera are all varying examples) and to adopt the theory that the end justifies the means. Everywhere the world movement seems to be in the direction of centralised economies which can be made to ‘work’ in an economic sense but which are not democratically organised and which tend to establish a caste system. With this go the horrors of emotional nationalism and a tendency to disbelieve in the existence of objective truth because all the facts have to fit in with the words and prophecies of some infallible fuhrer. Already history has in a sense ceased to exist, ie. there is no such thing as a history of our own times which could be universally accepted, and the exact sciences are endangered as soon as military necessity ceases to keep people up to the mark. Hitler can say that the Jews started the war, and if he survives that will become official history. He can't say that two and two are five, because for the purposes of, say, ballistics they have to make four. But if the sort of world that I am afraid of arrives, a world of two or three great superstates which are unable to conquer one another, two and two could become five if the fuhrer wished it.

- Letter to H. J. Willmett (18 May 1944), published in The Collected Essays, Journalism, & Letters, George Orwell: As I Please, 1943-1945 (2000), edited by Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus[3]

- Ideas which became fundamental to Nineteen Eighty-Four.

- Secondly there is the fact that the intellectuals are more totalitarian in outlook than the common people. On the whole the English intelligentsia have opposed Hitler, but only at the price of accepting Stalin. Most of them are perfectly ready for dictatorial methods, secret police, systematic falsification of history etc. so long as they feel that it is on ‘our’ side.

- Letter to H. J. Willmett (18 May 1944), published in The Collected Essays, Journalism, & Letters, George Orwell: As I Please, 1943-1945 (2000), edited by Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus[4]

- Of course, fanatical Communists and Russophiles generally can be respected, even if they are mistaken. But for people like ourselves, who suspect that something has gone very wrong with the Soviet Union, I consider that willingness to criticize Russia and Stalin is the test of intellectual honesty. It is the only thing that from a literary intellectual's point of view is really dangerous.

- Letter to John Middleton Murry (5 August 1944), published in The Collected Essays, Journalism, & Letters, George Orwell: As I Please, 1943-1945 (2000), edited by Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus

- In my small way I have been fighting for years against the systematic faking of history which now goes on.

- Letter to Frank Barber (15 December 1944)

- The Collected Essays, Journalism & Letters, George Orwell: As I Please, 1943-1945, Editors: Sonia Orwell, Ian Angus. p. 292.

- Particularly on the Left, political thought is a sort of masturbation fantasy in which the world of facts hardly matters.

- "London Letter" in Partisan Review (Winter 1945)

- Autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful. A man who gives a good account of himself is probably lying, since any life when viewed from the inside is simply a series of defeats.

- "Benefit Of Clergy: Some Notes On Salvador Dalí," Dickens, Dali & Others: Studies in Popular Culture (1944) [5]

- So far as I can see, all political thinking for years past has been vitiated in the same way. People can foresee the future only when it coincides with their own wishes, and the most grossly obvious facts can be ignored when they are unwelcome.

- "London Letter" (December 1944), in Partisan Review (Winter 1945)

- It is fashionable to say that all the causes we fought for have been defeated, but this seems to me a gross exaggeration. The fact that after six years of war we can hold a General Election in a quite orderly way, and throw out a Prime Minister who has enjoyed almost dictatorial powers, shows that we have gained something by not losing the war.

- London Letter to Partisan Review (15 ? August 1945)

- The Collected Essays, Journalism & Letters, George Orwell: As I Please, 1943-1945, Editors: Sonia Orwell, Ian Angus. p. 394.

- At any given moment there is an orthodoxy, a body of ideas which it is assumed that all right-thinking people will accept without question. It is not exactly forbidden to say this, that or the other, but it is 'not done' to say it, just as in mid-Victorian times it was 'not done' to mention trousers in the presence of a lady. Anyone who challenges the prevailing orthodoxy finds himself silenced with surprising effectiveness. A genuinely unfashionable opinion is almost never given a fair hearing, either in the popular press or in the highbrow periodicals.

- "The Freedom of the Press", unused preface to Animal Farm (1945), published in Times Literary Supplement (15 September 1972)

- Thus, for example, tanks, battleships and bombing planes are inherently tyrannical weapons, while rifles, muskets, long-bows, and hand-grenades are inherently democratic weapons. A complex weapon makes the strong stronger, while a simple weapon — so long as there is no answer to it — gives claws to the weak.

- "You and the Atom Bomb", Tribune (19 October 1945)

- Looking at the world as a whole, the drift for many decades has been not towards anarchy but towards the reimposition of slavery. We may be heading not for general breakdown but for an epoch as horribly stable as the slave empires of antiquity. James Burnham's theory has been much discussed, but few people have yet considered its ideological implications — that is, the kind of world-view, the kind of beliefs, and the social structure that would probably prevail in a state which was at once unconquerable and in a permanent state of "cold war" with its neighbors.

Had the atomic bomb turned out to be something as cheap and easily manufactured as a bicycle or an alarm clock, it might well have plunged us back into barbarism, but it might, on the other hand, have meant the end of national sovereignty and of the highly-centralised police state. If, as seems to be the case, it is a rare and costly object as difficult to produce as a battleship, it is likelier to put an end to large-scale wars at the cost of prolonging indefinitely a "peace that is no peace."- "You and the Atom Bomb", Tribune (19 October 1945). Reprinted in George Orwell: The Collected Essays, Journalism & Letters, Volume 4: In Front of Your Nose 1946–1950 (2000) by Sonia Orwell, Ian Angus, p. 9.

- First documented use of the phrase "cold war".

- Scientific education for the masses will do little good, and probably a lot of harm, if it simply boils down to more physics, more chemistry, more biology, etc to the detriment of literature and history. Its probable effect on the average human being would be to narrow the range of his thoughts and make him more than ever contemptuous of such knowledge as he did not possess.

- "What is Science?", Tribune (26 October 1945)

- The whole idea of revenge and punishment is a childish day-dream. Properly speaking, there is no such thing as revenge. Revenge is an act which you want to commit when you are powerless and because you are powerless: as soon as the sense of impotence is removed, the desire evaporates also.

- "Revenge is Sour", Tribune (9 November 1945)

- Actually there is little acute hatred of Germany left in this country, and even less, I should expect to find, in the army of occupation. Only the minority of sadists, who must have their "atrocities" from one source or another, take a keen interest in the hunting-down of war criminals and quislings.

- "Revenge is Sour", Tribune (9 November 1945)

- The relative freedom which we enjoy depends of public opinion. The law is no protection. Governments make laws, but whether they are carried out, and how the police behave, depends on the general temper in the country. If large numbers of people are interested in freedom of speech, there will be freedom of speech, even if the law forbids it; if public opinion is sluggish, inconvenient minorities will be persecuted, even if laws exist to protect them.

- "Freedom of the Park", Tribune (7 December 1945)

- Serious sport has nothing to do with fair play. It is bound up with hatred, jealousy, boastfulness, disregard of all rules and sadistic pleasure in witnessing violence: in other words it is war minus the shooting.

- "The Sporting Spirit", Tribune (14 December 1945)

- It is just thinkable that books may some day be written by machinery....

- Review of A Coat of Many Colours: Occasional Essays by Herbert Read, Poetry Quarterly (Winter 1945)

- Each generation imagines itself to be more intelligent than the one that went before it, and wiser than the one that comes after it. This is an illusion, and one should recognise it as such, but one ought also to stick to one's own world-view, even at the price of seeming old-fashioned: for that world-view springs out of experiences that the younger generation has not had, and to abandon it is to kill one's intellectual roots.

- Review of A Coat of Many Colours: Occasional Essays by Herbert Read, Poetry Quarterly (Winter 1945)

- ...but in his origins he is a Yorkshireman—that is, a member of a small, rustic, rather uncouth tribe whose members secretly believe all the other peoples of the earth to be just a little inferior to themselves. I think his best work comes from the Yorkshire strain in him.

- Review of A Coat of Many Colours: Occasional Essays by Herbert Read, Poetry Quarterly (Winter 1945)

- Out of this concourse of several hundred people, perhaps half of whom were directly connected with the writing trade, there was not a single one who could point out that freedom of the press, if it means anything at all, means the freedom to criticise and oppose.

- The Prevention of Literature. Polemic, No. 2 (January 1946)

- Totalitarianism demands, in fact, the continuous alteration of the past, and in the long run probably demands a disbelief in the very existence of objective truth.

- The Prevention of Literature. Polemic, No. 2 (January 1946)

- It would probably not be beyond human ingenuity to write books by machinery.

- The Prevention of Literature. Polemic, No. 2 (January 1946)

- Decline of the English Murder

- Essay title, Tribune (15 February 1946)

- In nearly seventy pages, it is astonishing how little he says, and how impressively he says it.

- Review. The Cosmological Eye by Henry Miller. Tribune (22 February 1946)

- The quickest way of ending a war is to lose it.

- "Second Thoughts on James Burnham". Polemic, (May 1946)

- Anyone who cares to examine my work will see that even when it is downright propaganda it contains much that a full-time politician would consider irrelevant. I am not able, and do not want, completely to abandon the world view that I acquired in childhood. So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the Earth, and to take pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information. It is no use trying to suppress that side of myself. The job is to reconcile my ingrained likes and dislikes with the essentially public, non-individual activities that this age forces on all of us.

It is not easy. It raises problems of construction and of language, and it raises in a new way the problem of truthfulness.- "Why I Write", Gangrel (Summer 1946)

- The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.

- "Why I Write," Gangrel (Summer 1946)

- The Spanish war and other events in 1936-37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects.

- "Why I Write," Gangrel (Summer 1946)

- Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand.

- "Why I Write," Gangrel (Summer 1946)

- If I had to make a list of six books which were to be preserved when all others were destroyed, I would certainly put Gulliver's Travels among them.

- "Politics vs. Literature: An Examination of Gulliver's Travels" (1946)

- In my opinion, nothing has contributed so much to the corruption of the original idea of socialism as the belief that Russia is a socialist country and that every act of its rulers must be excused, if not imitated. And so for the last ten years, I have been convinced that the destruction of the Soviet myth was essential if we wanted a revival of the socialist movement.

- Preface to the Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm, as published in The Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters of George Orwell: As I please, 1943-1945 (1968)

- The real division is not between conservatives and revolutionaries but between authoritarians and libertarians.

- Letter to Malcolm Muggeridge (4 December 1948), quoted in Malcolm Muggeridge: A Life (1980) by Ian Hunter

- If publishers and editors exert themselves to keep certain topics out of print, it is not because they are frightened of prosecution but because they are frightened of public opinion. In this country intellectual cowardice is the worst enemy a writer or journalist has to face, and that fact does not seem to me to have had the discussion it deserves.

- Original (unused) preface to Animal Farm (1945); as published in George Orwell: Some Materials for a Bibliography (1953) by Ian R. Willison

- I have never visited Russia and my knowledge of it consists only of what can be learned by reading books and newspapers. Even if I had the power, I would not wish to interfere in Soviet domestic affairs: I would not condemn Stalin and his associates merely for their barbaric and undemocratic methods. It is quite possible that, even with the best intentions, they could not have acted otherwise under the conditions prevailing there.

But on the other hand it was of the utmost importance to me that people in western Europe should see the Soviet regime for what it really was. Since 1930 I had seen little evidence that the USSR was progressing towards anything that one could truly call Socialism. On the contrary, I was struck by clear signs of its transformation into a hierarchical society, in which the rulers have no more reason to give up their power than any other ruling class. Moreover, the workers and intelligentsia in a country like England cannot understand that the USSR of today is altogether different from what it was in 1917. It is partly that they do not want to understand (i.e. they want to believe that, somewhere, a really Socialist country does actually exist), and partly that, being accustomed to comparative freedom and moderation in public life, totalitarianism is completely incomprehensible to them.- Original preface to Animal Farm; as published in George Orwell: Some Materials for a Bibliography (1953) by Ian R. Willison

- I am well acquainted with all the arguments against freedom of thought and speech — the arguments which claim that it cannot exist, and the arguments which claim that it ought not to. I answer simply that they don't convince me and that our civilization over a period of four hundred years has been founded on the opposite notice. For quite a decade past I have believed that the existing Russian régime is a mainly evil thing, and I claim the right to say so, in spite of the fact that we are allies with the USSR in a war which I want to see won. If I had to choose a text to justify myself, I should choose the line from Milton:

- By the known rules of ancient liberty.

- The word ancient emphasizes the fact that intellectual freedom is a deep-rooted tradition without which our characteristic western culture could only doubtfully exist. From that tradition many of our intellectuals are visibly turning away. They have accepted the principle that a book should be published or suppressed, praised or damned, not on its merits but according to political expediency. And others who do not actually hold this view assent to it from sheer cowardice.

- Original preface to Animal Farm; as published in George Orwell: Some Materials for a Bibliography (1953) by Ian R. Willison

- If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.

- Original preface to Animal Farm; as published in George Orwell: Some Materials for a Bibliography (1953) by Ian R. Willison

- Sometimes paraphrased as "Liberty is telling people what they do not want to hear."

- The point is that we are all capable of believing things which we know to be untrue, and then, when we are finally proved wrong, impudently twisting the facts so as to show that we were right. Intellectually, it is possible to carry on this process for an indefinite time: the only check on it is that sooner or later a false belief bumps up against solid reality, usually on a battlefield.

- "In Front of Your Nose", Tribune (22 March 1946)

- To see what is in front of one's nose needs a constant struggle.

- "In Front of Your Nose," Tribune (22 March 1946)

- Certainly we ought to be discontented, we ought not simply to find out ways of making the best of a bad job, and yet if we kill all pleasure in the actual process of life, what sort of future are we preparing for ourselves? If a man cannot enjoy the return of spring, why should he be happy in a labour-saving Utopia? What will he do with the leisure that the machine will give him?

- "Some Thoughts on the Common Toad", Tribune (12 April 1946)

- I have always suspected that if our economic and political problems are ever really solved, life will become simpler instead of more complex, and that the sort of pleasure one gets from finding the first primrose will loom larger than the sort of pleasure one gets from eating an ice to the tune of a Wurlitzer. I think that by retaining one's childhood love of such things as trees, fishes, butterflies and — to return to my first instance — toads, one makes a peaceful and decent future a little more probable, and that by preaching the doctrine that nothing is to be admired except steel and concrete, one merely makes it a little surer that human beings will have no outlet for their surplus energy except in hatred and leader worship.

- "Some Thoughts on the Common Toad," Tribune (12 April 1946)

- The atom bombs are piling up in the factories, the police are prowling through the cities, the lies are streaming from the loudspeakers, but earth is still going round the sun, and neither the dictators nor the bureaucrats, deeply as they disapprove of the process, are able to prevent it.

- "Some Thoughts on the Common Toad," Tribune (12 April 1946, page 10, last paragraph)

- It was only after the Soviet régime became unmistakably totalitarian that English intellectuals, in large numbers, began to show an interest in it. Burnham, although the English russophile intelligentsia would repudiate him, is really voicing their secret wish: the wish to destroy the old, equalitarian version of Socialism and usher in a hierarchical society where the intellectual can at last get his hands on the whip.

- "Second Thoughts on James Burnham," Polemic (summer 1946)

- In a Society in which there is no law, and in theory no compulsion, the only arbiter of behaviour is public opinion. But public opinion, because of the tremendous urge to conformity in gregarious animals, is less tolerant than any system of law. When human beings are governed by "thou shalt not", the individual can practise a certain amount of eccentricity: when they are supposedly governed by "love" or "reason", he is under continuous pressure to make him behave and think in exactly the same way as everyone else.

- "Politics vs. Literature: An Examination of Gulliver's Travels," Polemic (September/October 1946) - Full text online

- People talk about the horrors of war, but what weapon has man invented that even approaches in cruelty to some of the commoner diseases? "Natural" death, almost by definition, means something slow, smelly and painful.

- "How the Poor Die", Now (November 1946)

- The thing that politicians are seemingly unable to understand is that you cannot produce a vigorous literature by terrorising everyone into conformity.

- As I Please. Tribune (3 January 1947)

- In The Managerial Revolution, Burnham foretold the rise of three super-states which would be unable to conquer one another and would divide the world between them.

- Burnham's View of the Contemporary World Struggle. New Leader (New York) (29 March 1947)

- In reality there is no kind of evidence or argument by which one can show that Shakespeare, or any other writer, is ‘good’. Nor is there any way of definitely proving that — for instance — Warwick Beeping is ‘bad’. Ultimately there is no test of literary merit except survival, which is itself an index to majority opinion. Artistic theories such as Tolstoy's are quite worthless, because they not only start out with arbitrary assumptions, but depend on vague terms (‘sincere’, ‘important’ and so forth) which can be interpreted in any way one chooses.

- "Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool," Polemic (March 1947) - Full text online

- A tragic situation exists precisely when virtue does not triumph but when it is still felt that man is nobler than the forces which destroy him.

- "Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool," Polemic (March 1947)

- Shakespeare starts by assuming that to make yourself powerless is to invite an attack. This does not mean that everyone will turn against you (Kent and the Fool stand by Lear from first to last), but in all probability someone will. If you throw away your weapons, some less scrupulous person will pick them up. If you turn the other cheek, you will get a harder blow on it than you got on the first one. This does not always happen, but it is to be expected, and you ought not to complain if it does happen. The second blow is, so to speak, part of the act of turning the other cheek. First of all, therefore, there is the vulgar, common-sense moral drawn by the Fool: "Don't relinquish power, don't give away your lands." But there is also another moral. Shakespeare never utters it in so many words, and it does not very much matter whether he was fully aware of it. It is contained in the story, which, after all, he made up, or altered to suit his purposes. It is: "Give away your lands if you want to, but don't expect to gain happiness by doing so. Probably you won't gain happiness. If you live for others, you must live for others, and not as a roundabout way of getting an advantage for yourself."

- "Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool," Polemic (March 1947)

- A normal human being does not want the Kingdom of Heaven: he wants life on earth to continue. This is not solely because he is "weak," "sinful" and anxious for a "good time." Most people get a fair amount of fun out of their lives, but on balance life is suffering, and only the very young or the very foolish imagine otherwise. Ultimately it is the Christian attitude which is self-interested and hedonistic, since the aim is always to get away from the painful struggle of earthly life and find eternal peace in some kind of Heaven or Nirvana. The humanist attitude is that the struggle must continue and that death is the price of life.

- "Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool," Polemic (March 1947)

- There are people who are convinced of the wickedness both of armies and of police forces, but who are nevertheless much more intolerant and inquisitorial in outlook than the normal person who believes that it is necessary to use violence in certain circumstances. They will not say to somebody else, ‘Do this, that and the other or you will go to prison’, but they will, if they can, get inside his brain and dictate his thoughts for him in the minutest particulars. Creeds like pacifism and anarchism, which seem on the surface to imply a complete renunciation of power, rather encourage this habit of mind. For if you have embraced a creed which appears to be free from the ordinary dirtiness of politics — a creed from which you yourself cannot expect to draw any material advantage — surely that proves that you are in the right? And the more you are in the right, the more natural that everyone else should be bullied into thinking likewise.

- "Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool," Polemic (March 1947)

- No one can look back on his schooldays and say with truth that they were altogether unhappy.

- "Such, Such Were The Joys" (May 1947); published in Partisan Review (September/October 1952)

- Football, it seemed to me, is not really played for the pleasure of kicking the ball about, but is a species of fighting.

- "Such, Such Were The Joys" (May 1947); published in Partisan Review (September/October 1952)

- Therefore there is always the danger that the United States will break up any European coalition by drawing Britain out of it.

- Towards European Unity. Partisan Review (July/August 1947)

- Threats to freedom of speech, writing and action, though often trivial in isolation, are cumulative in their effect and, unless checked, lead to a general disrespect for the rights of the citizen.

- "The Freedom Defence Committee" in "The Socialist Leader (18 September 1948); also in The Collected Essays, Journalism, & Letters, George Orwell; Vol. IV: In front of your nose, 1945-1950 (2000), p. 447

- I always disagree, however, when people end up saying that we can only combat Communism, Fascism or what not if we develop an equal fanaticism. It appears to me that one defeats the fanatic precisely by not being a fanatic oneself, but on the contrary by using one's intelligence.

- Letter to Richard Rees (3 March 1949), The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, Vol. 4: In front of your nose, 1945-1950 (1968), ed. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus, p. 478

- It is difficult for a statesman who still has a political future to reveal everything that he knows: and in a profession in which one is a baby at 50 and middle-aged at seventy-five, it is natural that anyone who has not actually been disgraced should feel that he still has a future.

- Review of Their Finest Hour by Winston Churchill, New Leader (14 May 1949)

- One cannot really be Catholic & grown-up.

- "Extracts from a Manuscript Notebook" (1949), The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, vol. 4 (1968)

- At 50, everyone has the face he deserves.

- "Extracts from a Manuscript Notebook" (1949), The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, vol. 4 (1968)

- I have always thought there might be a lot of cash in starting a new religion.

- The Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters of George Orwell, Volume 1: An Age Like This, 1920-1940 (1968), edited by Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus Orwell, p. 304

- [Nineteen Eighty-Four] was based chiefly on communism, because that is the dominant form of totalitarianism, but I was trying chiefly to imagine what communism would be like if it were firmly rooted in the English speaking countries, and was no longer a mere extension of the Russian Foreign Office.

- Letter to Sidney Sheldon, (Aug. 9, 1949) The Other Side of Me (Autobiography), Hachette Book Group USA, New York, NY, 2006, Chapter 20, p. 53. Sheldon purchased the stage rights to1984 from Orwell.

- What is needed is the right to print what one believes to be true, without having to fear bullying or blackmail from any side.

- 1946 exchange with Randall Swingler; quoted in Every Intellectual's Big Brother: George Orwell's Literary Siblings, John Rodden, University of Texas Press, Austin, p. 30

- The Paris slums are a gathering-place for eccentric people — people who have fallen into solitary, half-mad grooves of life and given up trying to be normal or decent. Poverty frees them from normal standards of behaviour, just as money frees people from work. Some of the lodgers in our hotel lived lives that were curious beyond words.

- Ch. 1

- I am trying to describe the people in our quarter, not for the mere curiosity, but because they are all part of the story. Poverty is what I am writing about, and I had my first contact with poverty in this slum. The slum, with its dirt and its queer lives, was first an object-lesson in poverty, and then the background of my own experiences. It is for that reason that I try to give some idea of what life was like there.

- Ch. 1

- "Ah, the poverty, the shortness the disappointment of human joy! For in reality car en realite, what is the duration of the supreme moment of love? It is nothing, an instant, a second perhaps. A second of ecstasy, and after that- dust, ashes, nothingness."

- Ch. 2, Charlie

- For, when you are approaching poverty, you make one discovery which outweighs some of the others. You discover boredom and mean complications and the beginnings of hunger, but you also discover the great redeeming feature of poverty: the fact that it annihilates the future. Within certain limits, it is actually true that the less money you have, the less you worry. When you have a hundred francs in the world you are liable to the most craven panics. When you have only three francs you are quite indifferent; for three francs will feed you till tomorrow, and you cannot think further than that. You are bored, but you are not afraid. You think vaguely, 'I shall be starving in a day or two--shocking, isn't it?' And then the mind wanders to other topics. A bread and margarine diet does, to some extent, provide its own anodyne. And there is another feeling that is a great consolation in poverty. I believe everyone who has been hard up has experienced it. It is a feeling of relief, almost of pleasure, at knowing yourself at last genuinely down and out. You have talked so often of going to the dogs--and well, here are the dogs, and you have reached them, and you can stand it. It takes off a lot of anxiety.

- Ch. 3

- There is only one way to make money at writing, and that is to marry a publisher's daughter.

- Ch. 4; a record of a remark by Orwell's fellow tramp Boris

- For, when you are approaching poverty, you make one discovery which outweighs some of the others. You discover boredom and mean complications and the beginnings of hunger, but you also discover the great redeeming feature of poverty: the fact that it annihilates the future. Within certain limits, it is actually true that the less money you have, the less you worry.

- Ch. 4

- Hunger reduces one to an utterly spineless, brainless condition, more like the after-effects of influenza than anything else. It is as though all one's blood had been pumped out and lukewarm water substituted.

- Ch. 7

- One always abandons something in retreat. Look at Napoleon at the Beresina! He abandoned his whole army.

- Ch. 7; a remark by Boris

- Fate seemed to be playing a series of extraordinarily unamusing jokes.

- Ch. 7

- It is fatal to look hungry. It makes people want to kick you.

- Ch. 9; a remark by Boris

- I only realized during my last week that I was being cheated, and, as I could prove nothing, only twenty-five francs were refunded. The doorkeeper played similar tricks on any employee who was fool enough to be taken in. He called himself a Greek, but in reality he was an Armenian. After knowing him I saw the force of the proverb "Trust a snake before a Jew and a Jew before a Greek, but don't trust an Armenian."

- Ch. 13

- Roughly speaking, the more one pays for food, the more sweat and spittle one is obliged to eat with it. ... Dirtiness is inherent in hotels and restaurants, because sound food is sacrificed to punctuality and smartness... The only food at the Hotel X which was ever prepared cleanly was the staff's.

- Ch. 14

- We crawled up to bed, tumbled down half dressed, and stayed there ten hours. Most of my Saturday nights went like this. On the whole, the two hours when one was perfectly and wildly happy seemed worth the subsequent headache. For many men in the quarter, unmarried and with no future to think of, the weekly drinking-bout was the one thing that made life worth living.

- Ch. 17

- Looking round that filthy room, with raw meat lying among the refuse on the floor, and cold, clotted saucepans sprawling everywhere, and the sink blocked and coated with grease, I used to wonder whether there could be a restaurant in the world as bad as ours. But the other three all said they had been in dirtier places.

- Ch. 21; on the state of the kitchen at the newly opened Auberge.

- How sweet the air does smell — even the air of a back-street in the suburbs — after the shut-in, subfaecal stench of the spike!

- Ch. 27, on the morning after Orwell is let out of his first tramps' accommodation, or 'spike'.

- He had two subjects of conversation, the shame and come-down of being a tramp, and the best way of getting a free meal.

- Ch. 28, on Paddy the tramp

- Paddy and I had scarcely a wink of sleep, for there was a man near us who had some nervous trouble, shell-shock perhaps, which made him cry out 'Pip!' at irregular intervals. It was a loud, startling noise, something like the toot of a small motor-horn. You never knew when it was coming, and it was a sure preventer of sleep. ...he must have kept ten or twenty people awake every night. He was an example of the kind of thing that prevents one from ever getting enough sleep when men are herded as they are in these lodging houses.'

- Ch. 29

- Being a beggar, he said, was not his fault, and he refused either to have any compunction about it or to let it trouble him. He was the enemy of society, and quite ready to take to crime if he saw a good opportunity. He refused on principle to be thrifty. In the summer he saved nothing, spending his surplus earnings on drink, as he did not care about women. If he was penniless when winter came on, then society must look after him. He was ready to extract every penny he could from charity, provided that he was not expected to say thank you for it. He avoided religious charities, however, for he said it stuck in his throat to sing hymns for buns. He had various other points of honour; for instance, it was his boast that never in his life, even when starving, had he picked up a cigarette end. He considered himself in a class above the ordinary run of beggars, who, he said, were an abject lot, without even the decency to be ungrateful.

- On "Bozo", in Ch. 30

- He was an embittered atheist (the sort of atheist who does not so much disbelieve in God as personally dislike Him), and took a sort of pleasure in thinking that human affairs would never improve. Sometimes, he said, when sleeping on the Embankment, it had consoled him to look up at Mars or Jupiter and think that there were probably Embankment sleepers there. He had a curious theory about this. Life on earth, he said, is harsh because the planet is poor in the necessities of existence. Mars, with its cold climate and scanty water, must be far poorer, and life correspondingly harsher. Whereas on earth you are merely imprisoned for stealing sixpence, on Mars you are probably boiled alive. This thought cheered Bozo, I do not know why. He was a very exceptional man.

- Ch. 30

- Beggars do not work, it is said; but then, what is work? A navvy works by swinging a pick. An accountant works by adding up figures. A beggar works by standing out of doors in all weathers and getting varicose veins, bronchitis etc. It is a trade like any other; quite useless, of course — but, then, many reputable trades are quite useless. And as a social type a beggar compares well with scores of others. He is honest compared with the sellers of most patent medicines, high-minded compared with a Sunday newspaper proprietor, amiable compared with a hire-purchase tout-in short, a parasite, but a fairly harmless parasite. He seldom extracts more than a bare living from the community, and, what should justify him according to our ethical ideas, he pays for it over and over in suffering.

- Ch. 31

- The most bitter insult one can offer to a Londoner is "bastard" — which, taken for what it means, is hardly an insult at all.

- Ch. 32

- The whole business of swearing, especially English swearing, is mysterious. Of its very nature swearing is as irrational as magic-- indeed, it is a species of magic. But there is also a paradox about it, namely this: Our intention in swearing is to shock and wound, which we do by mentioning something that should be kept secret--usually something to do with the sexual functions. But the strange thing is that when a word is well established as a swear word, it seems to lose its original meaning; that is, it loses the thing that made it into a swear word. A word becomes an oath because it means a certain thing, and, because it has become an oath, it ceases to mean that thing.

- Ch. 32

- It is curious how people take it for granted that they have a right to preach at you and pray over you as soon as your income falls below a certain level.

- Ch. 33

- My story ends here. It is a fairly trivial story, and I can only hope that it has been interesting in the same way as a trivial diary is interesting. ... At present I do not feel I have seen more than the fringe of poverty.

Still, I can point to one or two things I have definitely learned by being hard up. I shall never again think that all tramps are drunken scoundrels, nor expect a beggar to be grateful when I give him a penny, nor be surprised if men out of work lack energy, nor subscribe to the Salvation Army, nor pawn my clothes, nor refuse a handbill, nor enjoy a meal at a smart restaurant. That is a beginning.- Ch. 38

Burmese Days (1934)

edit- Ellis was one of those people who constantly nag others to echo their own opinions.

- Ch. II

- Living a lie the whole time — the lie that we're here to uplift our poor black brothers instead of to rob them ... it corrupts us, it corrupts us in ways you can't imagine.

- John Flory, Ch. III

- Beauty is meaningless until it is shared.

- Ch. IV

- It is one of the tragedies of the half-educated that they develop late, when they are already committed to some wrong way of life.

- Ch. V

- I always think they're rather charming-looking, the Burmese. They have such splendid bodies! Just think what sights you'd see in England if people went about half naked as they do here!

- John Flory, Ch X

- An earthquake is such fun when it is over.

- Ch. XV

- Is there anything in the world more graceless, more dishonouring, than to desire a woman whom you will never have?

- Ch XX

- Envy is a horrible thing. It is unlike all other kinds of suffering in that there is no disguising it, no elevating it into tragedy. It is more than merely painful, it is disgusting.

- Ch. XX

Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936)

edit- Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not money, I am become as a sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge; and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not money, I am nothing. And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not money, it profiteth me nothing. Money suffereth long, and is kind; money envieth not; money vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up, doth not behave unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil; rejoiceth not in iniquity, but rejoiceth in the truth; beareth all things, believeth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things. ... And now abideth faith, hope, money, these three; but the greatest of these is money.

- opening lines, I Corinthians xiii (adapted)

- Money, once again; all is money. All human relationships must be purchased with money. If you have no money, men won't care for you, women won't love you; won't, that is, care for you or love you the last little bit that matters. And how right they are, after all! For, moneyless, you are unlovable. Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels. But then, if I haven't money, I DON'T speak with the tongues of men and of angels.

- In a country like England you can no more be cultured without money than you can join the Cavalry Club.

- That devastating omniscience! That noxious, horn-spectacled refinement! And the money that such refinement means! For after all, what is there behind it, except money? Money for the right kind of education, money for influential friends, money for leisure and peace of mind, money for trips to Italy. Money writes books, money sells them. Give me not righteousness, O Lord, give me money, only money.

- Ch. 1

- Of all types of human being, only the artist takes it upon himself to say that he 'cannot' work. But it is quite true; there ARE times when one cannot work. Money again, always money! Lack of money means discomfort, means squalid worries, means shortage of tobacco, means ever-present consciousness of failure - above all, it means loneliness. How can you be anything but lonely on two quid a week? And in loneliness no decent book was ever written.

- Ch. 2

- No need to repeat the blasphemous comments which everyone who had known Gran'pa Comstock made on that last sentence. But it is worth pointing out that the chunk of granite on which it was inscribed weighed close on five tons and was quite certainly put there with the intention, though not the conscious intention, of making sure that Gran'pa Comstock shouldn't get up from underneath it. If you want to know what a dead man's relatives really think of him, a good rough test is the weight of his tombstone.

- Ch. 3

- Gordon and his friends had quite an exciting time with their 'subversive ideas'. For a whole year they ran an unofficial monthly paper called the Bolshevik, duplicated with jellygraph. It advocated Socialism, free love, the dismemberment of the British Empire, the abolition of the Army and Navy, and so on and so forth. It was great fun. Every intelligent boy of sixteen is a Socialist. At that age one does not see the hook sticking out of the rather stodgy bait.

- Ch. 3

- There are two ways to live, he decided. You can be rich, or you can deliberately refuse to be rich. You can possess money, or you can despise money; the one fatal thing is to worship money and fail to get it.

- Ch.3

- Most of the employees were the hard-boiled, Americanized, go-getting type to whom nothing in the world is sacred, except money. They had their cynical code worked out. The public are swine; advertising is the rattling of a stick inside a swill-bucket. And yet beneath their cynicism there was the final naivete, the blind worship of the money-god.

- Ch. 3

- It was queer. All over England young men were eating their hearts out for lack of jobs, and here was he, Gordon, to whom the very word 'job' was faintly nauseous, having jobs thrust unwanted upon him. It was an example of the fact that you can get anything in this world if you genuinely don't want it.

- Ch. 3

- He had reached the age when the future ceases to be a rosy blur and becomes actual and menacing.

- Ch. 3

- That is the devilish thing about poverty, the ever-recurrent thing - loneliness. Day after day with never an intelligent person to talk to; night after night back to your godless room, always alone. Perhaps it sounds rather fun if you are rich and sought-after; but how different it is when you do it from necessity!

- Ch. 4

- When you have no money your life is one long series of snubs.

- Ch. 4

- Gordon put his hand against the swing door. He even pushed it open a few inches. The warm fog of smoke and beer slipped through the crack. A familiar, reviving smell; nevertheless as he smelled it his nerve failed him. No! Impossible to go in. He turned away. He couldn't go shoving into that saloon bar with only fourpence halfpenny in his pocket. Never let other people buy your drinks for you! The first commandment of the moneyless. He made off down the dark pavement.

- Ch. 4

- Social failure, artistic failure, sexual failure - they are all the same. And lack of money is at the bottom of them all.

- Ch. 4

- No rich man ever succeeds in disguising himself as a poor man; for money, like murder, will out.

- Ch. 5

- This life we live nowadays! It's not life, it's stagnation, death-in-life. Look at all these bloody houses, and the meaningless people inside them! Sometimes I think we're all corpses. Just rotting upright.

- Ch. 5

- Money is the one thing you must never mention when you are with people richer than yourself. Or if you do, then it must be money in the abstract, money with a big 'M', not the actual concrete money that's in your pocket and isn't in mine.

- Ch. 5

- After all, it's only what Marx said. Every ideology is a reflection of economic circumstances.

- Ch. 5

- Poverty is spiritual halitosis.

- Ch. 5

- Hermione always yawned at the mention of Socialism, and refused even to read Antichrist. 'Don't talk to me about the lower classes,' she used to say. 'I hate them. They smell.' And Ravelston adored her.

- Ch. 5

- What rot it is to talk about Socialism or any other ism when women are what they are! The only thing a woman ever wants is money; money for a house of her own and two babies and Drage furniture and an aspidistra. The only sin they can imagine is not wanting to grab money. No woman ever judges a man by anything except his income. Of course she doesn't put it to herself like that. She says he's such a nice man - meaning that he's got plenty of money. And if you haven't got money you aren't nice. You're dishonoured, somehow. You've sinned. Sinned against the aspidistra.

- Ch. 5

- This woman business! What a bore it is! What a pity we can't cut it right out, or at least be like the animals—minutes of ferocious lust and months of icy chastity. Take a cock pheasant, for example. He jumps up on the hen's backs without so much as a with your leave or by your leave. And no sooner is it over than the whole subject is out of his mind. He hardly even notices his hens any longer; he ignores them, or simply pecks them if they come too near his food. He is not called upon to support his offspring, either. Lucky pheasant! How different from the lord of creation, always on the hop between his memory and his conscience

- Ch. 6

- Marriage is only a trap set for you by the money-god. You grab the bait; snap goes the trap; and there you are, chained by the leg to some 'good' job till they cart you to Kensal Green. And what a life! Licit sexual intercourse in the shade of the aspidistra. Pram-pushing and sneaky adulteries. And the wife finding you out and breaking the cut-glass whisky decanter over your head.

- Ch. 6

- Without money, you can't be straightforward in your dealings with women. For without money, you can't pick and choose, you've got to take what women you can get; and then, necessarily, you've got to break free of them. Constancy, like all other virtues, has got to be paid for in money.

- Ch. 6

- Why is it that one can't borrow from a rich friend and can from a half-starved relative?

- Ch. 7

- He would only drift and sink, drift and sink, like the others of his family; but worse than them - down, down into some dreadful sub-world that as yet he could only dimly imagine. It was what he had chosen when he declared war on money. Serve the money-god or go under; there is no other rule.

- Ch. 7

- She looked at him helplessly. After all, it was no use. There was this money-business standing in the way - these meaningless scruples which she had never understood but which she had accepted merely because they were his. She felt all the impotence, the resentment of a woman who sees an abstract idea triumphing over common sense.

- Ch. 10

- Their friendship was at an end, it seemed to him. The evil time when he had lived on Ravelston had spoiled everything. Charity kills friendship.

- Ch. 10

- Before, he had fought against the money code, and yet he had clung to his wretched remnant of decency. But now it was precisely from decency that he wanted to escape. He wanted to go down, deep down, into some world where decency no longer mattered; to cut the strings of his self-respect, to submerge himself—to sink, as Rosemary had said. It was all bound up in his mind with the thought of being under ground. He liked to think of the lost people, the under-ground people: tramps, beggars, criminals, prostitutes. It is a good world that they inhabit, down there in their frowzy kips and spikes. He liked to think that beneath the world of money there is that great sluttish underworld where failure and success have no meaning; a sort of kingdom of ghosts where all are equal. That was where he wished to be, down in the ghost-kingdom, below ambition. It comforted him somehow to think of the smoke-dim slums of South London sprawling on and on, a huge graceless wilderness where you could lose yourself forever.

- Ch. 10

- One's got to change the system, or one changes nothing.

- Ch. 10

- The Americans always go one better on any kind of beastliness, whether it is ice-cream soda, racketeering or theosophy.

- Ch. 11

Homage to Catalonia (1938)

edit- Chiefly I remember the horsy smells, the quavering bugle-calls (all our buglers were amateurs--I first learned the Spanish bugle-calls by listening to them outside the Fascist lines), the tramp-tramp of hobnailed boots in the barrack yard, the long morning parades in the wintry sunshine, the wild games of football, fifty a side, in the gravelled riding--school.

- I have no particular love for the idealised "worker" as he appears in the bourgeois Communist's mind, but when I see an actual flesh-and-blood worker in conflict with his natural enemy, the policeman, I do not have to ask myself which side I am on.

- All Spaniards, we discovered, knew two English expressions. One was "O.K., baby", the other was a word used by the Barcelona whores in their dealings with English sailors, and I am afraid the compositors would not print it.

- I have the most evil memories of Spain, but I have very few bad memories of Spaniards.