Isaac Deutscher

Polish historian and Marxist (1907-1967)

Isaac Deutscher (3 April 1907 – 19 August 1967) was a Polish-born Marxist writer, journalist and political activist who moved to the United Kingdom at the outbreak of World War II. He is best remembered as a biographer of Leon Trotsky and Joseph Stalin and as a commentator on Soviet and Jewish affairs.

If both behaved rationally, they would not become enemies. The man who escaped from the blazing house, having recovered, would have tried to help and console the other sufferer; and the latter might have realised that he was the victim of circumstances over which neither of them had control.

Quotes

edit- [Stalin] had found Russia working with wooden ploughs and leaving it equipped with atomic piles.

- [A]ll the non-Stalinist versions concur in the following: the generals did indeed plan a coup d'état... The main part of the coup was to be a palace revolt in the Kremlin, culminating in the assassination of Stalin. A decisive military operation outside the Kremlin, an assault on the headquarters of the G.P.U., was also prepared. Tukhachevsky was the moving spirit of the conspiracy... He was, indeed, the only man among all the military and civilian leaders of that time who showed in many respects a resemblance to the original Bonaparte and could have played the Russian First Consul. The chief political commissar of the army, Gamarnik, who later committed suicide, was initiated into the plot. General Yakir, the commander of Leningrad, was to secure the co-operation of his garrison. Generals Uberovich, commander of the western military district, Kork, commander of the Military Academy in Moscow, Primakow, Budienny's deputy in the command of the cavalry, and a few other generals were also in the plot.

- Stalin: A Political Biography, second edition (London: Oxford University Press, 1967), pp. 360-361. Quote from Ludo Martens's Another view of Stalin, pp. 176.

- Can’t you approach the young worker and tell him that the way to live is to work for life and not for death? Is it beneath American scholars to try to do that?... Your only salvation is in carrying the idea of socialism to the working class and coming back to storm—to storm, yes, to storm—the bastions of capitalism.

- Quoted in S. Unger, "Deutscher and the New Left in America", in D. Horowitz (ed).

- Outside the party, formless revolutionary frustration mingled with distinctly counter-revolutionary trends. Since the ruling group had singled out Trotsky as a target for attack he automatically attracted the spurious sympathy of many who had hitherto hated him. As he made his appearance in the streets of Moscow [in the spring of 1924], he was spontaneously applauded by crowds in which idealist communists rubbed shoulders with Mensheviks, Social Revolutionaries, and the new bourgeoisie of the NEP, by all those indeed who, for diverse reasons hoped for a change

- Stalin, Pelican, 1966, p. 279. Quote from Harpal Brar's Trotskyism or Leninism?, p. 25.

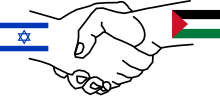

- A man once jumped from the top floor of a burning house in which many members of his family had already perished. He managed to save his life; but as he was falling he hit a person standing down below and broke that person’s legs and arms. The jumping man had no choice; yet to the man with the broken limbs he was the cause of his misfortune.

If both behaved rationally, they would not become enemies. The man who escaped from the blazing house, having recovered, would have tried to help and console the other sufferer; and the latter might have realised that he was the victim of circumstances over which neither of them had control.

But look what happens when these people behave irrationally. The injured man blames the other for his misery and swears to make him pay for it. The other, afraid of the crippled man’s revenge, insults him, kicks him, and beats him up whenever they meet. The kicked man again swears revenge and is again punched and punished. The bitter enmity, so fortuitous at first, hardens and comes to overshadow the whole existence of both men and to poison their minds. - Still we must exercise our judgment and must not allow it to be clouded by emotions and memories, however deep or haunting. We should not allow even invocations of Auschwitz to blackmail us into supporting the wrong cause.

- To justify or condone Israel's wars against the Arabs is to render Israel a very bad service indeed and to harm its own long-term interest. Israel's security, let me repeat, was not enhanced by the wars of 1956 and 1967; it was undermined and compromised by them.

- "The Arab-Israeli War", New Left Review (23 June, 1967)

- The ex-communist is the problem child of contemporary politics.

- The Ex-Communists Conscience

Quotes about Isaac Deutscher

edit- Like universalism, secularism was important to modern Jewish social thought. "Jewish secularism is a revolt grounded in the tradition it rejects," argues David Biale, citing Isaac Deutscher's often-quoted remark about "the non-Jewish Jew," made in a 1954 speech. The "Jewish heretic who transcends Jewry belongs to a Jewish tradition, Deutscher asserted. Although Deutscher had his eye on European intellectuals, including Spinoza, Marx, Freud, Trotsky, and Rosa Luxemburg, the same could be said of American radical thinkers and activists such as Emma Goldman, who celebrated the Day of Atonement, the holiest night of the Jewish year, at the anarchists' festive Yom Kippur Ball. Individuals such as these moved beyond the confines of Jewry, crossing boundaries they considered too narrow. "Their minds matured where the most diverse cultural influences crossed and fertilized each other, Deutscher wrote. They lived on the margins or in the nooks and crannies of their respective nations. "They were each in society and yet not in it, of it and yet not of it." Like their European forebears in this tradition, pioneer Jewish women's liberationists in the U.S. were well assimilated into the culture of their times, but nevertheless, in disclosures to this author and at public events related to this project, they acknowledged a sense of difference based on their ethnicity and gender. This otherness helped take these activists "beyond the boundaries of Jewry," in Deutscher's words, enabling them to "rise in thought above their societies, above their nations, above their times and generations... to strike out mentally into wide new horizons and far into the future."

- Joyce Antler Jewish Radical Feminism: Voices from the Women’s Liberation Movement (2020)

- Isaac Deutscher, master biographer of Leon Trotsky (or, as I like to think of him, Lev Bronstein) was one of many prophetic voices: "As long as a solution to the problem is sought in nationalist terms both Arab and Jew are condemned to move within a vicious circle of hatred and revenge."

- Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz The Colors of Jews: Racial Politics and Radical Diasporism (2007)

- The ideas of Jews like Marx and Rosa Luxemburg fired Jewish generation who were mostly non-Zionist, believing that if social revolution could ignite throughout the world there would be less and less room for anti-Semitism in a socialist international community. Many of that Eastern European generation emigrated to America to vitalize labor, antiracist, and socialist movements in the United States. But even Zionist pioneers, as the Marxist historian Isaac Deutscher points out, were imprinted with revolutionary socialist ideals, which they carried to Palestine: ideas of egalitarian community, of mending the division between mental and manual labor. Writing in the 1950s and early 1960s of a very new Israel, Deutscher remarks that as a young Marxist he had been anti-Zionist; after the Final Solution he described himself as a "non-Zionist" a position he would argue with leading Israelis, including David Ben-Gurion and Moshe Sharett. Critical of nationalism, recognizing Zionism's inevitable realisation at the end of World War II, he was certainly taken with Israel's energies and contradictions; he felt the utopian, collective, secular attractions of the kibbutz and also saw its role as military outpost: "The bastions of Israel's Utopian socialism bristle with Sten-guns." He did not minimize Israeli danger; his sense of the meaning of Palestinian dispossession and displacement now seems tone-deaf for an internationalist. (As was common in the 1960s, he recognized no Palestinians, only Arabs in general.) He also noted that Israel's economy, only partly because of Arab boycotts, had virtually no base apart from American Jewish donations and U.S. aid...Rereading it in the past months, I found it mostly acute, generous, accessible-the essays of a former cheder prodigy from Poland who, intended for a rabbi, turned from religion; got expelled from the Polish Communist Party over the question of international social revolution versus "socialism in one country"; lived in exile; became an anti-Stalinist historian who eloquently made English his fourth or fifth language; wrote respected and lasting biographies of both Stalin and Trotsky; and to the end kept his eye on Jewish complexity and its relationship to the hope of international socialism. In 1954 he wrote of Middle Eastern politics: "As long as a solution... is sought in nationalistic terms both Arab and Jew are condemned to move within a vicious circle of hatred and revenge. . . . In the long run a way out may be found beyond the nation-state, perhaps within the broader framework of a Middle East federation...Isaac Deutscher ended his 1954 essay on "Israel's Spiritual Climate": "...Sometimes it is only the music of the future to which it is worth listening."

- Adrienne Rich "Jewish Days and Nights" in Tony Kushner and Alisa Solomon, eds., Wrestling with Zion: Progressive Jewish-American Responses to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict (2003) and A Human Eye: Essays on Art in Society, 1997-2008 (2009)