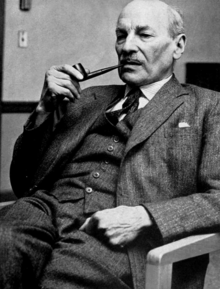

Clement Attlee

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee KG OM CH FRS PC (3 January 1883 – 8 October 1967) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951. Coming from an upper middle class background, Attlee was converted to socialism through working in the East End of London and became MP for Limehouse in 1922 (later Walthamstow West from 1950–55). He served as Deputy Prime Minister in Winston Churchill's war cabinet during World War II. He was elected Labour Party leader in 1935 and won a landslide victory in the 1945 election; his government put in place the welfare state including the National Health Service. Attlee was known for his laconic turn of phrase.

Quotes

edit- … the Peace Treaties must be scrapped … I stand for no more war and no more secret diplomacy.

- Extract from his 1922 election address, quoted in T.W. Walding (ed.), Who's Who in the New Parliament:Members and their pledges (Philip Gee, London, 1922), p. 35

- You may produce a case here and there of abuse of the dole: you may produce an occasional man who marches with the unemployed and has a bad record; but every Member of this House who has been in a contested election and has come into personal contact with the unemployed knows that the great mass of unemployed men are those same men who saved us during the War. They are the same men who stood side by side in the trenches. They are the heroes of 1914 and 1918, though they may be pointed out as the Bolshevists of to-day.

- Speech in the House of Commons (23 November 1922)

Deputy Leader of the Labour Party

edit- [N]othing short of a world state will be really effective in preventing war. As long as you rely for security on a number of national armaments you will have the difficulty as to who shall bell the cat in case of need, while you will have general staffs in all countries planning future wars. I want us to come out boldly for a real long-range policy which will envisage the abolition of the conception of the individual sovereign state... A united navy to police the seas of the world could be attained and would incidentally bring enormous pressure to bear on Japan. The next thing would be an international air force and an international air service... The basis of such a move would have to be a frank recognition that all states must surrender a large degree of sovereignty and that the Peace Treaties must be revised. On this basis one must then proceed to build up a world structure politically and economically... This may sound very visionary but I am convinced that unless we see the world we want it is vain to try to build a permanent habitation for Peace and that temporary structures will catch fire very soon if we wait any longer.

- Letter to Tom Attlee (1 January 1933), quoted in W. Golant, 'The Emergence of C. R. Attlee as Leader of the Parliamentary Labour Party in 1935', The Historical Journal, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Jun., 1970), p. 323

- I think that the whole of the movement towards dictatorships in Europe has reached its highest point and that there is a decline in the movement towards dictatorships owing to the failure of the dictators. I think that Hitler and his movement is the last move in the suggestion that somehow or other you can secure the world by getting some wonderful individual who is going to set everything right. [Interruption.] We have always taken that view on these Benches, and I am pleased to see by the applause on the Benches opposite that there is no inclination on their part to take Sir Oswald Mosley too seriously. I think we can generally say to-day that this dictatorship is gradually falling down. [Interruption.] I can quite understand the attitude of hon. Members opposite. We on this side are quite happy.

- Speech in the House of Commons (13 July 1934). His remarks about dictatorships gradually falling down was a reference to the Night of the Long Knives in Nazi Germany a fortnight before.

- We have absolutely abandoned any idea of nationalist loyalty. We are deliberately putting a world order before our loyalty to our own country.

- Speech to the Labour Party Conference in Southport (2 October 1934) , quoted in Talus, Your Alternative Government (1945), p. 17 and D. M. Touche, Britain's Lost Victory (1941).

- We are told in the White Paper that there is danger against which we have to guard ourselves. We do not think you can do it by national defence. We think you can only do it by moving forward to a new world – a world of law, the abolition of national armaments with a world force and a world economic system. I shall be told that that is quite impossible.

- Speech in the House of Commons (11 March 1935). Attlee's concluding observation was met by Conservative cries of "Hear, hear", with one MP shouting "Tell that to Hitler" according to The Times of 12 March 1935.

- The nationalist and imperialist delusions that run through all this document are far more wild than any idealist dreams of the future that we hold. But we say that if there is this menace, it is not going to be met by any policy of alliances. It is not going to be met by attack. We loath and detest the military spirit, the tyrannical spirit which has shown itself all over the world. You will never beat this by attack; you will only beat it by putting something far bigger in its place.

- Speech in the House of Commons on the National Government's White Paper on Defence (11 March 1935)

Leader of the Opposition

edit- Mr. Chamberlain's Budget was the natural expression of the character of the present Government. There was hardly any increase allowed for the services which went to build up the life of the people, education and health. Everything was devoted to piling up the instruments of death. The Chancellor expressed great regret that he should have to spend so much on armaments, but said that it was absolutely necessary and was due only to the actions of other nations. One would think to listen to him that the Government had no responsibility for the state of world affairs.

- Broadcast (22 April 1936), quoted in "Mr. Attlee on a war budget", The Times (23 April 1936), p. 16.

- The Government has now resolved to enter upon an arms race, and the people will have to pay for their mistake in believing that it could be trusted to carry out a policy of peace. … This is a War Budget. We can look in the future for no advance in Social Legislation. All available resources are to be devoted to armaments.

- Broadcast (22 April 1936), quoted in "Mr. Attlee on a war budget", The Times (23 April 1936), p. 16.

- Socialism is not the invention of an individual. It is essentially the outcome of economic and social conditions. The evils that Capitalism brings differ in intensity in different countries, but, the root cause of the trouble once discerned, the remedy is seen to be the same by thoughtful men and women. The cause is the private ownership of the means of life; the remedy is public ownership.

- The Labour Party in Perspective (Left Book Club, 1937), p. 15

- Socialists do not propose to substitute the domination of society by one privileged class for that of another. They seek to abolish class distinctions altogether. The abolition of classes is fundamental to the Socialist conception of society.

- The Labour Party in Perspective (Left Book Club, 1937), p. 145

- All the major industries will be owned and controlled by the community, but there may well exist for a long time many smaller enterprises which are left to be carried on individually... the interests of the community as a whole must come before that of any sectional group... the managers and technicians must be given reasonable freedom if they are to work efficiently, a freedom within the general economic plan... the workers must be citizens and not wage slaves.

- The Labour Party in Perspective (Left Book Club, 1937), p. 153

- When we are returned to power we want to put in the statute book an act which will make our people citizens of the world before they are citizens of this country.

- The Labour Party in Perspective (Left Book Club, 1937)

- I agree with the prime minister that the condition of the world is serious, and that everyone who speaks on these subjects must speak with a full sense of responsibility, but that does not mean, in my view, that there should be a lack of plain speaking, but that we ought to see the facts for what they really are. I must say that I was profoundly disappointed with the speech of the prime minister, because it seemed to me that he had misconceived the whole issue that lives before us. He suggested that there was being fought in Spain, in the opinion of some people, a struggle between two sides, two rival systems. I do not think that is the issue that is facing us to-day. The world to-day is faced with a contest between two sides, and those two sides are whether the rule of law in international affairs shall prevail, or the rule of lawless force. That is the issue that faces us, and we must look at this Spanish struggle in its true perspective.

- 25 June 1937, during the British Parliamentary debates on the Spanish Civil War. As quoted by John Cowans (Editor) in Modern Spain: A Documentary History (2003). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, paperback, p. 194

- We all feel relief that war has not come this time. Every one of us has been passing through days of anxiety; we cannot, however, feel that peace has been established, but that we have nothing but an armistice in a state of war. We have been unable to go in for care-free rejoicing. We have felt that we are in the midst of a tragedy. We have felt humiliation. This has not been a victory for reason and humanity. It has been a victory for brute force. At every stage of the proceedings there have been time limits laid down by the owner and ruler of armed force. The terms have not been terms negotiated; they have been terms laid down as ultimata. We have seen to-day a gallant, civilised and democratic people betrayed and handed over to a ruthless despotism. We have seen something more. We have seen the cause of democracy, which is, in our view, the cause of civilisation and humanity, receive a terrible defeat.

- Speech in the House of Commons against the Munich Agreement (3 October 1938)

- The events of these last few days constitute one of the greatest diplomatic defeats that this country and France have ever sustained. There can be no doubt that it is a tremendous victory for Herr Hitler. Without firing a shot, by the mere display of military force, he has achieved a dominating position in Europe which Germany failed to win after four years of war. He has overturned the balance of power in Europe. He has destroyed the last fortress of democracy in Eastern Europe which stood in the way of his ambition.

- Speech in the House of Commons against the Munich Agreement (3 October 1938)

- Not Churchill. Sixty-five, old for a Churchill.

- Harold Wilson, Memoirs 1916-1964: The Making of a Prime Minister (Weidenfeld & Nicolson and Michael Joseph, London, 1986), p. 54.

- At the University College 'gaudy' in Oxford, December 1939, when the dons suggested Winston Churchill should be made Prime Minister.

- In regard to...action in the South Atlantic, we all desire to join in the tribute paid to the gallantry of our sailors. It is one of the almost inevitable conditions of sea warfare that so much of the fighting is done between adversaries of very different strengths, and the way in which our ships, despite their smaller gun-power, tackled and stuck to this very powerful enemy vessel and forced her to take refuge, is worthy of the highest traditions of the British Navy.

- Speech in the House of Commons after the Battle of the River Plate when the German cruiser Admiral Graf Spee was forced to harbour by the Royal Navy (14 December 1939)

War Cabinet

edit- There is a denial of the value of the individual. Christianity affirms the value of each individual soul. Nazism denies it. The individual is sacrificed to the idol of the German Leader, German State or the German race. The ordinary citizen is allowed to hear and think only as the rulers decree.

- Speech (May 1940), quoted in the The Listener (Vol. 23), BBC (1940)

- I have to inform the House that the present situation is so critical that the Government are compelled to seek special powers from the House by a Bill to be passed through all its stages in both Houses of Parliament to-day. The situation is grave... The Government are convinced that now is the time when we must mobilise to the full the whole resources of this country. We must throw all our weight into the struggle. Every private interest must give way to the urgent needs of the community. We cannot know what the next few weeks or even days may bring forth, but whatever may come we shall meet it as the British people in the past have met dangers and overcome them. But it is necessary that the Government should be given complete control over persons and property, not just some persons of some particular class of the community, but of all persons, rich and poor, employer and workman, man or woman, and all property.

- Speech in the House of Commons introducing the Emergency Powers Act 1940 (22 May 1940)

- The British people now realise the danger with which they are faced, and know that in the event of a German victory everything they have built up will be destroyed. The Germans kill not only men, but ideas. Our people are resolved as never before in their history.

- Remarks to the meeting of the Supreme War Council in the War Office in the Rue Saint-Dominique, Paris (31 May 1940), quoted in Winston Churchill, The Second World War, Volume Two: Their Finest Hour [1949] (1951), p. 105

- Real national unity sprang from the things which we had in common; the greater that common interest, the stronger the nation in peace as well as in war. It is because in this country we all enjoyed freedom of speech, freedom of conscience, and the right to choose and change our Governments that we were united. The continent of Europe had fallen before Hitler because of its disunity. By playing on the rivalries and jealousies of the nations he had divided them and devoured them in detail. There was not enough realization of the common interest of all in our civilization to overcome sectional ambitions and fears. Had Europe been united in spirit the Nazi monster would have been strangled at birth.

- Speech in Chesterfield (13 June 1941), quoted in The Times (14 June 1941), p. 2

- The aim of the Nazis was to enslave all the peoples, who were to be the mere instruments of the Germans, the Herrenfolk, the master class. To that we opposed the democratic ideal, whereby we saw the world as a community of nations, differing in their qualities but united in a comity of nations, like the citizens of a town, but recognizing each other's rights and uniting for common purposes.

- Speech in Chesterfield (13 June 1941), quoted in The Times (14 June 1941), p. 2

- Deeply as many people deplored the policy which at a critical moment in European history gave Hitler a free hand in the East to develop his ambitious schemes of domination, strongly opposed as we were to many features of the Soviet system, we had no hesitation in proclaiming that as enemies of our enemies we should do all we could to help the Russian people in their fight... It was not unlikely that Hitler hoped to be able to launch from Moscow a great peace offensive. He would like to proclaim himself the saviour of Europe from Bolshevism... He would deceive no one in the Government. The great mass of the people in this country and in the countries of the British Commonwealth and Empire would not be deceived. We would not make peace with the Nazi gang because such a peace would be no peace. It would be a betrayal of everything for which this country stood.

- Speech in Neath, South Wales after the German invasion of Russia (13 July 1941) , quoted in The Times (14 July 1941), p. 2

- It is one of the great achievements of our rule in India that, even if they do not entirely carry them out, educated Indians do accept British principles of justice and liberty. We are condemned by Indians not by the measures of Indian ethical conceptions but by our own, which we have taught them to accept. It is precisely this acceptance by politically conscious Indians of the principles of democracy and liberty which puts us in the position of being able to appeal to them to take part with us in the common struggle; but the success of this appeal and India's response does put upon us the obligation of seeing that we, as far as we may, make them sharers in the things for which we and they are fighting.

- Letter to the Cabinet (January 1942), quoted in Paul Addison, The Road to 1945 (1994), pp. 202-203

- We had had the help during the past 20 months...of a number of Dominion statesmen. Our touch with those who guided the destinies of the Commonwealth was very close and constant. That was very right and necessary, because we were all engaged in the same great venture, we were all defending a common heritage—the cause of freedom and democracy. The links which united us with the free peoples of the Commonwealth proved their strength, and as we stood together in war so we should stand together in peace to create a new and better world.

- Speech to the 65th anniversary luncheon of the United Wards' Club in the Connaught Rooms, London (23 February 1942), quoted in The Times (24 February 1942), p. 2

- Unity was essential to victory. The Government contained men of varied views and varied backgrounds but united by a common will to victory, a common acceptance of a way of life. That was what we were fighting for. Our civilization had received terrible wounds. In the British Commonwealth, among the free nations, we cherished the ideals of peace. We believed we could build a new world, purged of evil, and more splendid and good. In that great faith and hope we must bend all our energies in unity together; and...[I have] absolute confidence that, dark as were the clouds to-day, we could already descry the dawn.

- Speech to the 65th anniversary luncheon of the United Wards' Club in the Connaught Rooms, London (23 February 1942), quoted in The Times (24 February 1942), p. 2

- You may have the best machinery in the world, you may have adequate supplies of munitions, you may have the men, you may have the generals; but wars are fought out eventually always as contests of will, and there are needed in the responsible positions men who are prepared to give decisions, who are not afraid to take risks, men of inflexible will-power. In all these respects, I say, from very close working with him for the last two years, that we have in the Prime Minister a leader in war such as this country has rarely had in its long history.

- Speech in the House of Commons (19 May 1942)

- We can take a just pride in the great contribution to the common cause by all those who owe allegiance to the British Crown... In this great contest we are all engaged in a single enterprise. Soldiers, sailors, and airmen from the United Kingdom, from the British Commonwealth and the Empire, from the United States, and from many nations are found fighting side by side in many ocean and theatres of war. They know that they are engaged in a common service and are inspired by a common faith. In the Atlantic Charter the United Nations have declared the faith that is in them. Against the false gods of cruelty, hatred, and domination they have proclaimed their gospel of freedom, justice, and social security.

- Message (2 September 1942), quoted in The Times (3 September 1942), p. 2

- The path which the great Dominions were treading...was a path leading not to independence but to interdependence. One of the greatest mistakes made by our enemies—and they made it in the last war, too—was to under-estimate the strength of those invisible bonds uniting the free peoples of the British Commonwealth of Nations. The German was never happy unless he was in a mass. He was happiest of all when they were all performing the goose-step at the same time, whereas the British people, conscious of their unity though the seas might separate them, could march to their goal without rigidly keeping step.

- Speech to the Devonshire Club, London (14 May 1943), quoted in The Times (15 May 1943), p. 2

- I take it to be a fundamental assumption that whatever post-war international organisation is established, it will be our aim to maintain the British Commonwealth as an international entity, recognised as such by foreign countries... If we are to carry our full weight in the post-war world with the US and USSR, it can only be as a united British Commonwealth.

- 'The Relations of the British Commonwealth to the Post-War International Political Organisation' (June 1943), quoted in Correlli Barnett, The Lost Victory: British Dreams, British Realities 1945–1950 (1995), p. 51

- Here in this country, although our political divisions were deep, in time of need we were able to transcend them in the interests of the whole community. Throughout the British Commonwealth and Empire there were immense diversities of race, colour, creed, and degrees of civilization, yet the links that united all together, though often intangible, proved strong as steel in the day of trial. This was because, despite many shortcomings and failures to implement fully the ideals which we held, the British Commonwealth and Empire had stood for freedom and justice, and because we had learnt through long centuries the lesson of how to live together without attempting to exact regimented uniformity.

- Speech in Carmarthen, Wales (3 September 1943), quoted in The Times (4 September 1943), p. 2

- [T]he people of Britain and the Dominions were not much given to self-glorification. We were indeed inclined to a certain self-depreciation which was not always understood outside our own family of nations; but this was an occasion when they might take a proper pride in themselves. The world knew that in the critical time after Hitler's victories in 1940 it was the British Commonwealth and Empire that stood alone in defence of freedom for a whole year. It was British steadfastness that held the line while the forces of freedom were gathering.

- Speech to the conference of representatives of the British and Dominion Labour parties, Westminster, London (12 September 1944), quoted in The Times (13 September 1944), p. 8

- I returned last week...from visiting the Italian front. I was up with the Eighth Army, that Army which will always seem to me to epitomize the unity of our Commonwealth and Empire. I saw there in Italy Canadians, South Africans, and New Zealanders. I recalled talking with General Alexander the great deeds of the Australians. As I saw our lads from all our countries so fine and gallant, I was thrilled with pride.

- Speech to the conference of representatives of the British and Dominion Labour parties, Westminster, London (12 September 1944), quoted in The Times (13 September 1944), p. 8

- In the ranks of Labour there would be no faltering until victory was won and German and Japanese aggression had been utterly defeated. But they had reached a stage when they could look beyond war to peace. In all our parties there was a firm resolve to build up a world system of security that would prevent our fellow men and women again being subjected to the horror of war. The lesson of the war of 1914–18 was...only half learnt. The idea of the League of Nations was right, but it was not put into practice. This time we must see to it that an international order is established in the world with the power and the will, and not merely the desire, to prevent war breaking out again.

- Speech to the conference of representatives of the British and Dominion Labour parties, Westminster, London (12 September 1944), quoted in The Times (13 September 1944), p. 8

- [I]f peace is to be preserved we must see to it that the causes of war are removed. Freedom and democracy must be based not only on security but also on social justice. Hitlerism flourished on the breakdown of an outworn economic system. The world depression of 1930 was the opportunity of the gangsters. We must have planning for expansion and not restriction. Victory in war could only be achieved by putting the interest of the community before private profit and this was also the key to reconstruction after the war. Socialism had always been something far greater than an economic theory, far greater than the policy of a political party. It was a way of life. They sought to attain an organized society in which every human being would have the opportunity of living the good life—a society in which free men and women would cooperate together for the common good. The workers of the countries which had been under the yoke of tyranny would look to the Labour parties of the British Commonwealth for a lead and would not look in vain.

- Speech to the conference of representatives of the British and Dominion Labour parties, Westminster, London (12 September 1944), quoted in The Times (13 September 1944), p. 8

- [N]ext to the winning of the war the most vital matter was the building of peace on firm foundations... The young generation of Germans had been deliberately perverted and trained in savagery. With German thoroughness the very malleable youth of Germany had been moulded into the shape of their leaders. It would be a long time before they could be civilized. It was madness to expect that suddenly S.S. men and Hitler Youth would turn into good, peaceful citizens and democrats. The German and Japanese nations had for years been directed to false aims and ideals. A great moral and mental revolution would be required before they would be fit to be trusted. Both these nations must be disarmed and deprived of the power to start new wars, and there must be an organization to ensure peace and with power to enforce it.

- Speech to the Labour Party Conference in Caxton Hall, London (12 December 1944), quoted in The Times (13 December 1944), p. 2

- The League of Nations fell, not because its principles were wrong, but because they were not practised. A new world organization must be created. Its nucleus was in the United Nations, and its foundation stone the close cooperation of the British Commonwealth of Nations, the United States, and the U.S.S.R. ... They wanted an organization embracing small as well as great nations, but on the three, on account of their strength, the greatest responsibility for preserving the peace of the world must fall. A world organization to preserve peace must have power at its disposal. So long as there was a danger of wolves the sheep-dog must have strong teeth. It was time that the nations of Europe should settle down as good citizens in a world of States. In the British Commonwealth of Nations it was shown how freedom was compatible with unity. If peace was to be preserved there must be some cession of sovereignty, but membership of a large organization did not conflict with the reasonable claims of nations to live their own lives.

- Speech to the Labour Party Conference in Caxton Hall, London (12 December 1944), quoted in The Times (13 December 1944), p. 2

Leader of the Opposition

edit- When I listened to the Prime Minister's speech last night, in which he gave such a travesty of the policy of the Labour Party, I realized at once what was his object. He wanted the electors to understand how great was the difference between Winston Churchill, the great leader in war of a united nation, and Mr. Churchill, the party leader of the Conservatives. He feared lest those who had accepted his leadership in war might be tempted out of gratitude to follow him further. I thank him for having disillusioned them so thoroughly. The voice we heard last night was that of Mr. Churchill, but the mind was that of Lord Beaverbrook.

- Broadcast for the 1945 general election (5 June 1945), quoted in The Times (6 June 1945), p. 2

- The Prime Minister spent a lot of time painting to you a lurid picture of what would happen under a Labour Government in pursuit of what he called a Continental conception. He has forgotten that Socialist theory was developed by Robert Owen in Britain long before Karl Marx. He has forgotten that Australia, New Zealand, whose peoples have played so great a part in the war, and the Scandinavian countries have had Socialist Governments for years, to the great benefit of their peoples, with none of those dreadful consequences...When he talks of the danger of a secret police...he forgets that these things were actually experienced in this country only under the Tory Government of Lord Liverpool in the years of repression when the British people who had saved Europe from Napoleon were suffering deep distress. He has forgotten many things, including, when he talks of the danger of Labour mismanaging finance, his own disastrous record at the Exchequer over the gold standard.

- Broadcast (5 June 1945), quoted in The Times (6 June 1945), p. 2. Churchill had claimed in broadcast that a Labour government would have to rely on a Gestapo to carry out socialist policies

- I shall not waste time on this theoretical stuff, which seems to me to be a secondhand version of the academic views of an Austrian professor—Friedrich August von Hayek—who is very popular just now with the Conservative Party. Any system can be reduced to absurdity by this kind of theoretical reasoning, just as German professors showed theoretically that British democracy must be beaten by German dictatorship. It was not.

- Broadcast (5 June 1945), quoted in The Times (6 June 1945), p. 2. The Conservatives had used some of their paper ration for the election on Hayek's book The Road to Serfdom.

- The simple fact is that nothing would be more harmful to the post-war economic and social welfare of our country than that the Tory Party should again have charge of the nation's affairs. The Tory record of lamentable failure and muddle between the two world wars is a sharp warning which the people will do well to heed unless they prefer to delude themselves with false hopes now and indulge in vain regrets later. We did not fight and win the war for private profit or for any selfish national end, but to preserve the right of the people to live in freedom and to increase their opportunities to achieve by their own industry and service the conditions and standards of a secure and happy life. The Tory Party want to hand us back into the keeping of private profit-seeking enterprise which was responsible for the mass unemployment, the derelict areas, and the waste and misery of the years between the two wars. In the light of bitter experience that would be folly.

- Message to Labour candidates, quoted in The Times (29 June 1945), p. 2

- We of the Labour Party reject policies and measures which failed the nation then and will fail the nation now. We want to lay the foundations of a new and better Britain worthy of our great people. That is why we propose in the interests of the whole nation that the community should become the master of its economic progress and prosperity, instead of leaving control in private hands to be used primarily for the private advantage of a few. In short, we are standing for the common weal. But we need political power to enable us to give practical effect in Parliament to our great forward-looking policies. The nation has now the chance to give Labour the necessary power to do the job, and I appeal to the electors in the constituency which you are contesting to make certain of electing you to the new House of Commons.

- Message to Labour candidates, quoted in The Times (29 June 1945), p. 2

Prime Minister

edit- You will be judged by what you succeed at gentlemen, not by what you attempt.

- On formation of Government after landslide victory in 1945.

- To-day the United States stands out as the mightiest Power on earth, and yet America is a threat to no one. All know that she will never use her power for selfish aims or territorial aggrandisement in the future any more than she has done in the past. We look upon her forces and our own forces and those of other nations as instruments that must never be employed save in the interests of world security and for the repression of the aggressor.

- Address to the United States Congress (13 November 1945), quoted in The Times (14 November 1945), p. 4

- I think that some people over here imagine that the Socialists are out to destroy freedom, freedom of the individual, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and the freedom of the Press. They are wrong; the Labour Party is in the tradition of freedom-loving movements which have always existed in our country, but freedom has to be striven for in every generation, and those who threaten it are not always the same. Sometimes the battle of freedom has had to be fought against kings, sometimes against religious tyranny, sometimes against the power of the owners of the land, sometimes against the overwhelming strength of the moneyed interests. We in the Labour Party declare that we are in line with those who fought for Magna Carta and habeas corpus, with the Pilgrim Fathers, and with the signatories of the Declaration of Independence.

- Address to the United States Congress (13 November 1945), quoted in The Times (14 November 1945), p. 4. Aneurin Bevan said to Attlee afterwards: "That was a noble speech. I felt very proud", quoted in John Campbell, Nye Bevan and the Mirage of British Socialism (1987), p. 187

- The Old School Tie can still be seen on the Government benches.

- Address to the United States Congress (13 November 1945), quoted in The Times (14 November 1945), p. 8

- You have no right whatever to speak on behalf of the Government. Foreign affairs are in the capable hands of Ernest Bevin. His task is quite sufficiently difficult without the irresponsible statements of the kind you are making . . . I can assure you there is widespread resentment in the Party at your activities and a period of silence on your part would be welcome.

- Letter to Harold Laski, Chairman of the Labour Party (1946), quoted in David Butler and Gareth Butler, Twentieth Century British Political Facts (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), p. 289.

- During the war we had to stop producing the everyday things which we need in peacetime. We had to concentrate on war production and the bare necessities of existence. The natural result is that to-day we are short of the things which we need... You may ask why cannot we get what we want from abroad? The answer is that we can only get it if we can pay for it. Before the war many of the things which we got from abroad—food and raw material—were paid for by the interest on foreign investments, and by services rendered by us to people in other countries. During the war we had to sell our foreign investments to pay for the arms, food, and other things we needed. Apart from any temporary relief we may get by loans from our friends across the Atlantic, we can only buy from abroad now if we can pay by exporting goods or rendering services.

- Broadcast (3 March 1946), quoted in The Times (4 March 1946), p. 4

- What is this principle? It is not embodied in some narrow doctrinaire formula, as some of our opponents would suggest. Still less is it a particular economic or political formula laid down once for all. It is essentially a moral principle on which we believe the life of nations and of individuals should be ordered. That principle is the brotherhood of man.

- Speech to a London Labour Party rally in the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden (5 May 1946), quoted in The Times (6 May 1946), p. 3

- We are seeking to build up in this country a system of society in which there shall be freedom from want. We are seeking to join with others in extending that freedom from want all over the world, but we also seek to give to all peoples freedom from fear. The freedom from fear of war is not yet lifted from the men and women of the world. We are doing our utmost to make the United Nations Organization the instrument for banishing the fear of war from the world. But there are many countries to-day where there are other fears that oppress. Personal freedom is still far from complete in many countries. Freedom of conscience is still denied to many. Freedom of speech and freedom of the Press are still unknown in most areas of the world. A system of society that denies all of these other freedoms is not socialism, but only a form of collectivism.

- Speech to a London Labour Party rally in the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden (5 May 1946), quoted in The Times (6 May 1946), p. 3

- As a nation we have two tasks; the one is to provide goods and services for our home needs, the other is to pay for the food and raw materials which we must get from abroad. Before the war we were rich; we owned money and railways and so forth abroad. The income from these helped to pay for our imports; but we sold these in order to help to win the war. We have therefore borrowed large sums from Canada and the United States to tide us over while we build up again, but when this money runs out we must pay for what we want from our own resources. To do this we must devote a far larger part than ever before of the wealth we produce to pay for imports.

- Broadcast (18 March 1947), quoted in The Times (19 March 1947), p. 4

- Looking back today over the years, we may well be proud of the work which our fellow citizens have done in India. There have, of course, been mistakes, there have been failures, but we can assert that our rule in India will stand comparison with that of any other nation which has been charged with the ruling of a people so different from themselves.

- Speech in the House of Commons (10 July 1947)

- May I recall here a thing that is not always remembered, that just as India owes her unity and freedom from external aggression to the British, so the Indian National Congress itself was founded and inspired by men of our own race, and further, that any judgment passed on our rule in India by Indians is passed on the basis, not of what obtained in the past in India, but on the principles which we have ourselves instilled into them.

- Speech in the House of Commons (10 July 1947)

- Ever since the population of this little island grew large, trade has been its livelihood. We imported food and raw materials and paid for them by exports of coal and manufactures, by earnings from shipping and other services, and by interest on foreign investments. The first world war injured our position seriously, the second had far worse effects. When we stood alone in the second world war we threw all that we had into the battle... We sold our foreign assets. We reduced our production of civilian goods to a minimum. We lost nearly all our export trade and much of our shipping... We have, therefore, to face now before we have recovered from the effects of the war, and before our long-term plans have taken effect, the necessity of relying entirely on our own resources. This is a situation as serious as any that has faced us in our long history.

- Broadcast (10 August 1947), quoted in The Times (11 August 1947), p. 4

- A hundred years ago the year 1848 saw Liberals and Socialists in revolt all over Europe against absolute Governments which suppressed all opposition. It is ironical that to-day the absolutists who suppress opposition much more vigorously than the kings and emperors of the past masquerade under the name of upholders of democracy. It is a tragedy that a section of a movement which began in an endeavour to free the souls and bodies of men should have been perverted into an instrument for their enslavement.

- Broadcast (3 January 1948), quoted in The Times (5 January 1948), p. 4

- The history of Soviet Russia provides us with a warning here—a warning that without political freedom collectivism can quickly go astray and lead to new forms of oppression and injustice. For political freedom is not merely a noble thing in itself, essential for the full development of human personality—it is also a means of achieving economics rights and social justice, and of preserving these things when they have been won. Where there is no political freedom, privilege and injustice creep back. In Communist Russia 'privilege for the few' is a growing phenomenon, and the gap between the highest and lowest incomes is constantly widening. Soviet Communism pursues a policy of imperialism in a new form—ideological, economic, and strategic—which threatens the welfare and way of life of the other nations of Europe.

- Broadcast (3 January 1948), quoted in The Times (5 January 1948), p. 4

- At the one end of the scale are the Communist countries: at the other end the United States of America stands for individual liberty in the political sphere and for the maintenance of human rights. But its economy is based on capitalism, with all the problems which it presents, and with the characteristic extreme inequality of wealth in its citizens... Great Britain, like the other countries of western Europe, is placed geographically and from the point of view of economic and political theory between these two great continental States... Our task is to work out a system of a new and challenging kind, which combines individual freedom with a planned economy, democracy with social justice.

- Broadcast (3 January 1948), quoted in The Times (5 January 1948), p. 4

- A divinely inspired saint I know that I am expressing the views of the British people in offering to his fellow countrymen our deep sympathy in the loss of their greatest citizen. Mahatma Gandhi, as he was known in India, was one of the outstanding figures in the world today, but he seemed to belong to a different period of history. Living a life of extreme asceticism, he was revered as a divinely inspired saint by millions of his fellow countrymen. His influence extended beyond the range of his co-religionists. For a quarter of a century, this one man has been the major factor in every consideration of the Indian problem. He had become the expression of the aspirations of the Indian people for independence, but he was not just a nationalist. His most distinctive doctrine was that of non-violence. He believed in a method of passive resistance to those forces which he considered wrong. The sincerity and devotion with which he pursued his objectives are beyond all doubt. The hand of the murderer has struck him down and a voice which pleaded for peace and brotherhood has been silenced, but I am certain that his spirit will continue to animate his fellow countrymen and will plead for peace and concord.

- On death of Mahatma Gandhi 1948, London Calling, Issues 432-457, p. 4

- The nation's economic welfare depends largely upon our ability to make and sell the exports necessary to buy the imports we need to feed our people and keep our industry going. Our costs of production are of vital importance and they depend to a considerable extent on the amount which industry has to pay in profits, salaries and wages. These in turn in the form of individual incomes affect the total volume of money available in relation to the quantity of goods... It is essential, therefore, that there should be no further general increase in the level of personal incomes without at least a corresponding increase in the volume of production. Unless we are prepared to check any such tendency we shall find ourselves unable to fulfil our export task owing to the rise in costs, which will also be reflected in rising prices on the home market.

- Speech in the House of Commons (4 February 1948)

- In the circumstances it is much to be regretted that the men have not as yet responded generally to the call to return to work. A hold up of the food supplies of London will inevitably cause hardship and grave inconvenience to millions of householders; but this is by no means the end of the damage. The handling of the country's overseas trade normally stretches to the limit the capacity of our available shipping. A hold up of any length delays the turn-round of ships and cannot be made up subsequently. The stoppage cuts millions of dollars and other needed foreign currency off our earnings—and cuts them off finally. Already the prospect of attaining this month's export target is affected, the gap in the balance of our payments is widened and the pace of national recovery slowed down. I cannot believe that the general body of strikers have hitherto realised the true consequences of their action. They should return to work and allow any grievances they may feel to be dealt with by the proper machinery.

- Speech in the House of Commons on the London dock strike (23 June 1948)

- We shall not accept the Communist doctrine. That doctrine springs in the east. Oriental in its conception, it does not belong to the main stream of democratic thought. We in this country have our own democratic Socialism in which we believe, and we have a higher standard than they have in the east with regard to human rights and, I think, their way of life altogether. It is time those people recognised that we intend to carry on with our way.

- Speech to a rally of agricultural workers in Skegness (27 June 1948), quoted in The Times (28 June 1948), p. 4

- When you find anyone doing this look at him carefully. You will generally find he is a Communist or a fellow-traveller. These people do not want to see Europe restored to health. They want Europe to be weak and disturbed, because they think that the more wretched the people are the greater chance for the Communists. They have a vested interest in chaos.

- Speech to a rally of agricultural workers in Skegness (27 June 1948), quoted in The Times (28 June 1948), p. 4

- [W]e have asked the workers...to give the biggest possible output they can so that we may have a margin for export trade over the world which, when sold, will purchase us food and raw materials to keep our industry going. Now what does this term "keep industry going" mean? It is the difference between employment and unemployment... We depend on transport, shipping, and the movement of goods to keep up this output. Therefore, this strike is not a strike against capitalists or employers. It is a strike against your mates; a strike against the housewife; a strike against the ordinary common people who have difficulties enough now to manage on their shilling's worth of meat and the other rationed commodities.

- Broadcast on the London dock strike (28 June 1948), quoted in The Times (29 June 1948), p. 4

- [Y]ou are punishing thousands of innocent people and injuring your country. Who advised you to do this? Not people of great influence, but just a small nucleus who have been instructed for political reasons to take advantage of every little disturbance that takes place to cause the disruption of British economy, British trade, to undermine the Government and to destroy Britain's position... Your clear duty to yourselves, to your fellow citizens, and to your country is to return to work.

- Broadcast on the London dock strike (28 June 1948), quoted in The Times (29 June 1948), p. 4

- To-day the most comprehensive system of social security ever introduced into any country would start in Britain. The four Acts—National Insurance, Industrial Injuries, National Assistance, and National Health Service—represented the main body of the army of social security... We cannot create a scheme which gives the nation a whole more than they put into it, and it is always the general level of production that settles our standard of material well-being. Only higher output can give us more of the things we all need. This will decide the real value of the money payments.

- Broadcast (4 July 1948), quoted in The Times (5 July 1948), p. 6

- In every country in the world the Communist Party was out to hinder and to wreck... countries behind the Iron Curtain longed to come into the Marshall aid plan, which the Communist Party had decided against... They did not care what happened to the workers. They are only concerned with spreading what they call their own ideology.

- Speech in Walthamstow (11 January 1949), quoted in The Times (12 January 1949), p. 4

- The Atlantic Treaty is not aggressive. It is purely defensive. Those who attack it as offensive do so from a bad conscience. They take just the same line as the Nazis did when every attempt by the nations to get together was denounced as the encirclement of Germany. We seek by the pact to gain for the nations a sense of security which they so ardently desire. We seek by the organization of security to make the world safe against aggression and by pooling of strength to reduce the burden of armaments.

- Speech in Glasgow (10 April 1949), quoted in The Times (11 April 1949), p. 4

- A great campaign was launched to try to prevent the success of the Marshall plan in western Europe. Why? I am forced to the conclusion that it was because economic recovery in western Europe did not suit the foreign policy of the Soviet Government. Communism flourishes where the standard of life is low. The Communists did not care a jot for the sufferings of the people. If they had had their way—and their campaign against the Marshall plan has been an utter failure—the remarkable progress towards recovery which has taken place in western Europe would not have taken place. Aid from across the Atlantic would have been rejected. Your standard of life would have been reduced in order that there might be fertile ground for Communist propaganda.

- Speech in Glasgow (10 April 1949), quoted in The Times (11 April 1949), p. 4

- The responsibility for dividing the world rests squarely on the shoulders of the Kremlin. We do not give up hope of reuniting the world, but it can only be done if the Communists give up their ideological imperialism, their attempt to bring the whole world into line, to confine every single person within the straitjacket of Marx-Leninism. We in the Labour movement do not believe in this dead dull uniformity. On the contrary, we believe that variety is of the essence of a free society.

- Speech in Glasgow (10 April 1949), quoted in The Times (11 April 1949), p. 4

- There are some of our own people who still think that the Communists are the left wing of the Socialist movement. They are not. The Socialist movement was a movement for freedom in its widest sense. From the point of view of freedom, Communists are on the extreme right—more reactionary than some of the old tyrannies which we knew in the past. What is the thing for which we fight, for which the men with whom we feel the stir of sympathy throughout the ages have fought? Freedom. But that fight changes from age to age and the freedom that some men fought for may turn out to be tyranny. Communists, concentrating solely on the economic aspects of freedom...have produced the ghastly travesty of Socialism in the lands behind the iron curtain.

- Speech in Glasgow (10 April 1949), quoted in The Times (11 April 1949), p. 4

- [Attlee] reminded the delegates that it was vital to reduce costs by greater efficiency, which meant that both employers and employed had to seek in every way to attain it. He did not believe in lowering wages as a means of reducing costs, but equally it was necessary to realize that increases of wages that were not matched by increases of production would gravely impair their chances of getting rapidly over their difficulties. Increased demands for money payments, when there was no increase of goods to meet them led straight away to inflation. There was a danger that when a justifiable advance in wages for an under-paid section of the workers had been granted it resulted in demands from those who had enjoyed higher wages to maintain the same differential. This was bad economics and bad social morality. He had been disturbed at the evidence that some people were abusing the social services in such matters as sickness benefit. They could not have them sabotaged by misuse.

- Speech to the Trades Union Congress at Bridlington (7 September 1949), quoted 'Chronology, 18 August 1949 - 7 September 1949', Chronology of International Events and Documents, Vol. 5, No. 17 (18 August-7 September 1949), p. 583

- Our future as an industrial and trading nation depends on the success of our export drive. Increased production and increased exports are vital to the health of the shipping industry... Our fundamental need is still increased production to enable us to increase our volume of exports and so pay for our imports... That is the need of the country to-day.

- Speech to the Chamber of Shipping of the United Kingdom at the Dorchester Hotel (13 October 1949), quoted in The Times (14 October 1949), p. 4

- In the coming months the need is for the people of this country to do two things. First, to increase the national production; and, secondly, to exercise restraint in demands for increased incomes and self-control in expenditure... I am confident that in peace just as we did in war, Britain will conquer them by determination, hard work, and by the cooperation of all.

- Speech to the Chamber of Shipping of the United Kingdom at the Dorchester Hotel (13 October 1949), quoted in The Times (14 October 1949), p. 4

- We are having to make some heavy reductions in expenditure... They amount to about £250m. This is a very large sum... There has been some excessive and unnecessary resort to doctors for prescriptions. This must be checked. A charge, not exceeding one shilling, for each prescription will now be imposed. Arrangements will be made to relieve old age pensioners of this charge.

- Broadcast (24 October 1949), quoted in The Times (25 October 1949), p. 2

- As you all know, ever since the end of the war Britain has been working against time. We must find a way to stand on our own feet, and that very soon. Since the end of the war, too, our reserves have been small. This means that any alteration in world trade conditions, any failure to produce and sell enough goods must land us in serious trouble... I would like every one of you, whether employer or employed, to start right away to consider how in your particular job you can increase and cheapen production, how you can check absenteeism and get the kind of public opinion in factory, mine, railway, or other workplace which will bring the person who is slacking up to the mark.

- Broadcast (24 October 1949), quoted in The Times (25 October 1949), p. 2

- ...the Welfare State can only endure if it is built on a sound economic foundation. If you are in a job and have to-day through national insurance a greater sense of security than ever before, remember its continuance depends on what you do. Don't leave it to the other man. I have told you that the position is critical. We have a great opportunity to set things right. Let us seize it.

- Broadcast (24 October 1949), quoted in The Times (25 October 1949), p. 2

- He understood that in the countries beyond the iron curtain the artist must watch his step very carefully. It was not enough to be a good painter, any more than it was enough to be a good scientist or writer. The practitioner in the arts and sciences must first and foremost be a good Marxist-Leninist. Were we in the same position when we viewed this year's Summer Exhibition we should look primarily at the pictures to see whether or not they were in harmony with the tenets of dialectical materialism. It was rather a terrible prospect... We might rejoice that in this country such views were held by only an insignificant fraction. In his own party the influence of William Morris far exceeded that of Karl Marx.

- Speech to the annual dinner of the Royal Academy at Burlington House (27 April 1950), quoted in The Times (28 April 1950), p. 4

- Aggression has started again in the Far East. The attack by the armed forces of North Korea on South Korea has been denounced as an act of aggression by the United Nations. No excuses, no propaganda by Communists, no introduction of other factors can get over this fact. Here is a case of aggression. If the aggressor gets away with it, aggressors all over the world will be encouraged. The same results that led to the Second World War will follow; and another world war may result.

- Broadcast (30 July 1950) on the Korean War, quoted in The Times (31 July 1950), p. 4.

- The evil forces which are now attacking South Korea are part of a world-wide conspiracy against the way of life of the free democracies. Communists...are...engaged in an attempt to mould the whole world to their pattern of tyranny. They seek to sweep democracy and liberty from the world. They are ready to destroy our lives if we don't agree with them. They talk of freedom while they murder it. They talk of peace while they support aggression. They are ruthless and unscrupulous hypocrites who pretend to virtues which their philosophy rejects. The trouble is that quite a lot of well-meaning people are taken in by the Communists and their sham peace propaganda. What is happening in Korea should open their eyes.

- Broadcast (30 July 1950), quoted in The Times (31 July 1950), p. 4.

- I would ask you all to be on your guard against the enemy within. There are those who would stop at nothing to injure our economy and our defence. The price of liberty is still eternal vigilance. I know what a fine part the trade unionists of this country have played in our recovery effort. When they are asked to take unofficial action, which may hurt this country, let them just consider carefully whether the motives of those who ask them to strike are really concerned with the interests of the workers.

- Broadcast (30 July 1950), quoted in The Times (31 July 1950), p. 4

- To ensure peace we needed stronger armed forces as a deterrent to aggression.

- Broadcast (30 August 1950), quoted in The Times (31 August 1950), p. 4

- You see our new towns, our smiling countryside. I am proud of our achievements. There is an enormous amount more to do. Remember that we are a great crusading body, armed with a fervent spirit for the reign of righteousness on earth. Let us go forward into this fight in the spirit of William Blake: "I will not cease from mental strife/Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand/Till we have built Jerusalem/In England's green and pleasant land".

- Speech to the Labour Party Conference in Scarborough (1 October 1951), quoted in The Times (2 October 1951), p. 4

Leader of the Opposition

edit- Socialism was the only means of freeing the world from war and poverty. Socialism stood as a third alternative to a barbaric Communism and capitalism in a state of decay. Communism was a falsification of the principles of Socialism.

- Speech to the Swedish Social Democratic Party congress in Stockholm (5 June 1952), quoted in The Times (6 June 1952), p. 5

- I think that public opinion today likes a certain amount of pageantry. It is a great mistake to make government too dull. That, I think, was the fault of the German Republic after the First World War. They were very drab and dull; the trouble was that they let the devil get all the best tunes. Therefore, we on this side of the Committee believe that it is right to have a certain amount of pageantry, because it pleases people, and it also counteracts a tendency to other forms of excitement.

- Speech in the House of Commons on the civil list (9 July 1952)

- [A] movement like Mau Mau, out to murder Africans, Indians, and British, has got to be put down whether there is Conservative, Labour, or any other Government in charge.

- Press conference in Delhi (5 January 1953), quoted in The Times (6 January 1953), p. 6

- Malaya had a special contribution to make to world peace. One of the difficult problems of the world was to secure peace, freedom, and democratic government in countries inhabited by more than one community. It could not be done by one community seeking to dominate the others, but only by fair dealing and mutual tolerance. He sometimes thought that those who adopted extreme nationalist ideas did so because they had no constructive ideas and because an appeal to race prejudice saved them from an intolerable burden of thought. In his view the variations in the make-up of a community increased its value, and he wished good luck to all the peoples of Malaya in building up a great multi-racial community.

- Broadcast from Singapore (6 September 1954), quoted in The Times (7 September 1954), p. 7

- [T]he Conservative Party had been getting rid of the property owned by democracy and handing it over to groups of private profiteers.

- A play on the Conservative slogan "a property-owning democracy"; television broadcast from Walthamstow Town Hall (13 October 1954), quoted in The Times (14 October 1954), p. 4

Later life

edit- I joined the socialist movement because I did not like the kind of society we had and wanted something better.

- As It Happened, 1954. Also cited in Anthony Crosland, The Future of Socialism (1956), (p.116).

- You will not find much about what the Prime Minister does in the text-books. What he does is partly made up of convention and custom, but the nature of the office depends a great deal on the person who holds it... Make it [the Cabinet] as small as possible. Democracy means government by discussion, but it is only effective if you can stop people talking. Some of my early Cabinets were very small, but I arrived at the conclusion that 16 is the right number.

- Address to the Oxford University Law Society (14 June 1957), quoted in The Times (15 June 1957), p. 4.

- In choosing people for specific jobs previous experience should not be a guide. I never put a man in the job which he thought he knew. Often the 'experts' make the worst possible Ministers in their own fields. In this country we prefer rule by amateurs.

- Address to the Oxford University Law Society (14 June 1957), quoted in The Times (15 June 1957), p. 4.

- In Cabinet the important thing is to stop people from talking. Some people are loquacious, some are eloquent. I always used to point out that rhetoric is wasted on a Cabinet of hard-boiled politicians.

- Address to the Oxford University Law Society (14 June 1957), quoted in The Times (15 June 1957), p. 4.

- We never took a vote in the Cabinet that I can remember and the most important of all the Prime Minister's functions is to give a firm lead in Cabinet so that decisions can be taken quickly. The Prime Minister musn't always listen to those who talk most.

- Address to the Oxford University Law Society (14 June 1957), quoted in The Times (15 June 1957), p. 4.

- King George VI was always remarkably well informed, and I made a point of reading the latest telegrams before my weekly audience with him. A conscientious, constitutional monarch is a strong element of stability and continuity in our Constitution.

- Address to the Oxford University Law Society (14 June 1957), quoted in The Times (15 June 1957), p. 4.

- There is no such thing as the Shadow Cabinet. It is purely a Press term. The Prime Minister is by no means bound to include the members of the Shadow Cabinet in his Cabinet, or even in the Government. I myself left several out.

- Address to the Oxford University Law Society (14 June 1957), quoted in The Times (15 June 1957), p. 4

- ...the vital thing for the world to-day was to move away from the conception of the individual national State to something like a confederation of States in which some sovereign power was ceded to a wider Power. I do not think it need be much. At present what we have to give up is the right to make war.

- Broadcast in Sydney (25 October 1959), quoted in The Times (26 October 1959), p. 9

- I can remember no case where differences arose between Conservatives, Labour and Liberals along party lines. Certainly not in the War Cabinet. Certainly not in the big things... When one came to work out solutions they were often socialist ones, because one had to have organisation, and planning, and disregard private interests. But there was no opposition from Conservative Ministers. They accepted the practical solution whatever it was.

- Quoted in Francis Williams, A Prime Minister Remembers (1961), p. 37

- When I look at this as a proposal [i.e. British entry into the Common Market], it is really an extraordinary change. We used to put the Commonwealth first. It is quite obvious now that the Commonwealth comes second. We are going to be closer friends with the Germans, the Italians and the French than we are with the Australians or the Canadians. People are talking about what will happen thirty years hence: but, you know, twenty years ago I should never have imagined that we would be putting, as close friends, the Germans in front of the Canadians, the Australians, the New Zealanders, the Indians or anyone else. That does make for an entire revolution. It is also an entire revolution in the historic position of this country. I am not putting it forward that necessarily old things are right: I should be showing my age too clearly if I did that. It may be they are right; but make no mistake: this is an enormous change.

- Speech in the House of Lords on the British application to join the Common Market (2 August 1962)

- ...our geographical position put us in the centre of markets. That was one of the great strengths of our position. We did not have to look merely into Europe; we could look outside. We had our relationships with the Colonies overseas, later the Dominions; with the United States; with all continents, just because we were not tied up with the Continent of Europe. Now we are to be tied. It might be right, it may be wrong; but do not make any mistake: it is entirely different from anything we have had before. We are to become part of a larger whole, an appendage to Europe. It may be right now, but, historically, that has not been our position. We may have been at the centre of markets, but we have not been in one market and out of the others. We have had to fight against hostile tariffs; we have had to keep our end up. We have never put ourselves into a position in which we were inside a ring-fence with a number of Continental Powers. Make no mistake: it is an entire change.

- Speech in the House of Lords on the British application to join the Common Market (2 August 1962)

- When we come to the political point, I confess I feel gravely disturbed. We are allying ourselves with six nations of Europe; it may be more, but six at present. Four of those we rescued only twenty years or so ago from domination by the other two. Now we go cap in hand to the people whom we thought we beat in war. I am all for having agreements with everybody. I am all for getting on in the world with countries very differently organised to ourselves, capitalist countries, even Communist countries; but I am rather doubtful about these present proposals...It does not seem to me to be a very good tie-up for us; and if we are to go in irrevocably and tie ourselves up with other States, I think it is an extremely doubtful proposition for Britain. I think the political dangers are very great. Once you are in there, it is quite different from being in an organisation like NATO, which is a defence organisation directed against specific perils. It is a general link-up with Europe.

- Speech in the House of Lords on the British application to join the Common Market (2 August 1962)

- My noble friend Lord Morrison of Lambeth rather suggested that it was a really good Socialist policy to join up with these countries. I do not think that comes into it very much. They are not Socialist countries, and the object, so far as I can see, is to set up an organisation with a tariff against the rest of the world within which there shall be the freest possible competition between, capitalist interests. That might be a kind of common ideal. I daresay that is why it is supported by the Liberal Party. It is not a very good picture for the future...I believe in a planned economy. So far as I can see, we are to a large extent losing our power to plan as we want and submitting not to a Council of Ministers but a collection of international civil servants, able and honest, no doubt, but not necessarily having the best future of this country at heart...I think we are parting, to some extent at all events, with our powers to plan our own country in the way we desire. I quite agree that that plan should fit in, as far as it can, with a world plan. That is a very different thing from submitting our plans to be planned by a body of international civil servants, no doubt excellent men. I may be merely insular, but I have no prejudice in a Britain planned for the British by the British. Therefore, as at present advised, I am quite unconvinced either that it is necessary or that it is even desirable that we should go into the Common Market.

- Speech in the House of Lords on the British application to join the Common Market (2 August 1962)

- The Question of sovereignty is often raised. I am one of those who believe that in a modern world one has to give up a great deal of sovereignty. I am prepared to give up sovereignty to the world, but not to a selected number of European countries. That is not giving up something for world security; it is giving something up to sectional interests.

- Speech in the House of Lords on the British application to join the Common Market (8 November 1962)

- Unfortunately, in this country the propaganda for entering the Common Market has been largely based on defeatism. We are told that unless we do it we are going to have a terrible time. That is no way to go into a negotiation. You ought to go into a negotiation on the basis that they have need of you, not just you of them.

- Speech in the House of Lords on the British application to join the Common Market (8 November 1962)

- We are told that we have to accept the Treaty of Rome. I have read the Treaty of Rome pretty carefully, and it expresses an outlook entirely different from our own. It may be that I am insular, but I value our Parliamentary outlook, an outlook which has extended throughout the Commonwealth. That is not the same position that holds on the Continent of Europe. No one of these principal countries in the Common Market has been very successful in running Parliamentary institutions: Germany, hardly any experience; Italy, very little; France, a swing between a dictatorship and more or less anarchic Parliament, and not very successfully. As I read the Treaty of Rome, the whole position means that we shall enter a federation which is composed in an entirely different way. I do not say it is the wrong way. But it is not our way. In this set-up it is the official who really puts up all the proposals; the whole of the planning is done by officials. It seems to me that the Ministers come in at a later stage—and if there is anything like a Federal Parliament, at a later stage still. I do not think that that is the way this country has developed, or wishes to develop. I am all for working in with our Continental friends. I was one of those who worked to build up NATO; I have worked for European integration. But that is a very different thing from bringing us into a close association which, I may say, is not one for defence, or even just for foreign policy. The fact is that if the designs behind the Common Market are carried out, we are bound to be affected in every phase of our national life. There would be no national planning, except under the guidance of Continental planning—we shall not be able to deal with our own problems; we shall not be able to build up the country in the way we want to do, so far as I can see. I think we shall be subject to overall control and planning by others. That is my objection.

- Speech in the House of Lords on the British application to join the Common Market (8 November 1962)

- But as a matter of fact the idea of an integrated Europe is historically looking backward, and not forward. The noble Viscount was looking at the Holy Roman Empire. We never belonged to the Holy Roman Empire, and we never belonged to the reactionary organisation after 1815. We have always looked outward, out to the New World; and to-day we look out to the New World, and to Asia and Africa. I think that integration with Europe is a step backward. By all means let us get the greatest possible agreement between the various continents, but I am afraid that if we join the Common Market we shall be joining not an outward-looking organisation, but an inward-looking organisation. I think that Germany, for instance, which has probably the most powerful influence in the organisation, will not escape from looking at what she thought she was going to gain, and what she has lost. I do not think we have a new look there. I think that by marrying into Europe we are marrying a whole family of ancient prejudices and ancient troubles, and I would much rather see an Atlantic organisation. I would much rather work for the world organisation.

- Speech in the House of Lords on the British application to join the Common Market (8 November 1962)

- It's a very limited alliance, purely European, and it really, I think, breaks the unity of the Commonwealth. In my mind, the Commonwealth is immensely important, because it is multi-racial: Asiatic, African, Australian, and American. I think it's a retrograde step to go back to a purely European union.

- On his opposition to Britain joining the Common Market

- Interviewed on his eightieth birthday, 1963

- Attlee: I'm one of those people who are incapable of religious feeling.

Harris: Do you mean you have no feeling about Christianity, or that you have no feeling about God, Christ, and life after death?

Attlee: Believe in the ethics of Christianity. Can't believe in the mumbo jumbo.

Harris: Would you say you are an agnostic?

Attlee: I don't know.

Harris: Is there an after-life, do you think?

Attlee: Possibly.- To his official biographer Kenneth Harris two years before his death. In Kenneth Harris, Attlee, pp. 563-4.

- There were few who thought him a starter,

Many who thought themselves smarter.

But he ended PM,

CH and OM,

an Earl and a Knight of the Garter.- Kenneth Harris, Attlee (Weidenfeld and Nicholson, London, 1982)

- Self-penned limerick.

Attributed

edit- A Tory minister can sleep in ten different women's beds in a week. A Labour minister gets it in the neck if he looks at his neighbour's wife over the garden fence.

- Harold Wilson, Memoirs 1916-1964: The Making of a Prime Minister (Weidenfeld & Nicolson and Michael Joseph, London, 1986), p. 121.

- Can't publish. Don't rhyme, don't scan.

- Harold Wilson, Memoirs 1916-1964: The Making of a Prime Minister (Weidenfeld & Nicolson and Michael Joseph, London, 1986), p. 128.

- Response to John Strachey who had to ask permission to publish a collection of poems while a Minister.

- I move previous face!

- Harold Wilson, Memoirs 1916-1964: The Making of a Prime Minister (Weidenfeld & Nicolson and Michael Joseph, London, 1986), p. 128.

- To Sydney Silverman, a Labour MP who had arrived back at Parliament with a beard. Echoes the motion "I move previous business" used at Parliamentary Labour Party meetings to end discussion on a topic.

- Not up to the job.

- Explaining to John Parker why he was being sacked from the government in 1946.

- Quoted in Harold Wilson, Memoirs 1916-1964: The Making of a Prime Minister (Weidenfeld & Nicolson and Michael Joseph, London, 1986), p. 122.

- The Common Market. The so-called Common Market of six nations. Know them all well. Very recently this country spent a great deal of blood and treasure rescuing four of 'em from attacks by the other two.

- Peter Hennessy, The Prime Minister: The Office and its Holders since 1945 (Penguin, 2001), p. 173.

- Attlee's speech to a group of anti-Common Market Labour backbench MPs in 1967, as recalled by Douglas Jay to Peter Hennessy in 1983. This was Attlee's last ever speech.

Quotes about Attlee

edit- Charity is a cold grey loveless thing. If a rich man wants to help the poor, he should pay his taxes gladly, not dole out money at a whim.

- Francis Beckett, Clem Attlee, summarizing views expressed in Attlee's The Social Worker (1920). This quote is often mistakenly attributed to Attlee himself.

- The pro-Western policies of Clement Attlee’s Labour government (1945–51) were supported by the vast majority of the Labour Party and trade union movement. Communist and Soviet sympathisers within both were isolated, and the Communist Party was kept at a distance. This helped prevent the development of a strong radical Left, and was linked to the alliance between labour and capital that was to be important in the post-war mixed economy in Britain; although the emphasis on state control and regulation was damaging to entrepreneurial ethos. The Attlee government also decided by January 1947 to develop a British nuclear bomb. This policy was regarded as necessary for Britain’s independent security and independence. Throughout, the British government sought to play more than a secondary role to the USA. As a result, at considerable cost, Britain became the third nuclear power: the bomb was ready by 1952.

- Jeremy Black, The Cold War: A Military History (2015)