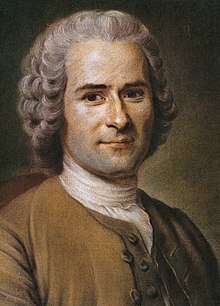

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer (1712–1778)

(Redirected from Rousseau)

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (June 28, 1712 – July 2, 1778) was a major French-speaking Genevan philosopher of Enlightenment whose political ideas influenced the French Revolution, the development of socialist theory, and the growth of nationalism.

- See also:

- Discourse on the Arts and Sciences (1750)

- Discourse on Inequality (1754)

- The Social Contract (1762)

- Emile, or On Education (1762)

- Confessions (Rousseau) (1782)

Quotes

edit- Let's go dance under the elms:

Step lively, young lassies.

Let's go dance under the elms:

Gallants, take up your pipes.- Le devin du village (1752)

- All that time is lost which might be better employed.

- As quoted in A Dictionary of Quotations in Most Frequent Use: Taken Chiefly from the Latin and French, but comprising many from the Greek, Spanish, and Italian Languages, translated into English (1809) by David Evans Macdonnel

- L'accent est l'âme du discours.

- Accent is the soul of language; it gives to it both feeling and truth.

- English translation as quoted in A Dictionary of Thoughts: Being a Cyclopedia of Laconic Quotations from the Best Authors of the World, Both Ancient and Modern (1908) by Tryon Edwards, p. 2.

- An honest man nearly always thinks justly.

- As quoted in A Dictionary of Thoughts: Being a Cyclopedia of Laconic Quotations from the Best Authors of the World, Both Ancient and Modern (1908) by Tryon Edwards, p. 277.

- A country cannot subsist well without liberty, nor liberty without virtue.

- As quoted in A Dictionary of Thoughts: Being a Cyclopedia of Laconic Quotations from the Best Authors of the World, Both Ancient and Modern (1908) by Tryon Edwards, p. 301.

- Days of absence, sad and dreary,

Clothed in sorrow's dark array,—

Days of absence, I am weary:

She I love is far away.- Day of Absence, reported in Bartlett's Familiar Quotations, 10th ed. (1919).

- Chère amie, ne savez-vous pas que la vertu est un état de guerre, et que, pour y vivre, on a toujours quelque combat à rendre contre soi?

- Virtue is a state of war, and to live in it means one always has some battle to wage against oneself.

- Julie ou la Nouvelle Héloïse (French), Sixième partie, Lettre VII Réponse (1761)

- Julie, or The New Heloise (English), Part Six, Letter VII Response, pg 560

- I shall need only myself to be happy.

- As quoted in The prophetic voice, 1758-1778 by Lester G. Crocke, p. 148.

- The supreme enjoyment is in satisfaction with oneself ; it is in order to deserve this satisfaction that we are placed on earth and endowed with freedom.

- As quoted in Dreamer of Democracy by James Miller and Jim Miller, p. 194.

- What good would it be to possess the whole universe if one were its only survivor?

- A Lasting Peace Through the Federation of Europe (1756)

- L'offenseur ne pardonne jamais.[1]

- Translation: The offender never forgives.

- Émile et Sophie, ou Les Solitaires, "Lettre Première" (1781)

Discourse on the Arts and Sciences (1750)

editDiscourse on Inequality (1754)

editThe Social Contract (1762)

editEmile, or On Education (1762)

editBook I

edit- Two conflicting types of educational systems spring from these conflicting aims. One is public and common to many, the other private and domestic. If you wish to know what is meant by public education, read Plato's Republic. Those who merely judge books by their titles take this for a treatise on politics, but it is the finest treatise on education ever written. In popular estimation the Platonic Institute stands for all that is fanciful and unreal. For my own part I should have thought the system of Lycurgus far more impracticable had he merely committed it to writing. Plato only sought to purge man's heart; Lycurgus turned it from its natural course. The public institute does not and cannot exist, for there is neither country nor patriot. The very words should be struck out of our language. The reason does not concern us at present, so that though I know it I refrain from stating it.

"To live is not to breathe; it is to act; it is to make use of our organs, our senses, our faculties, of all the parts of ourselves which give us the sentiment of our existence" (p. 42 (trans. Bloom)).

Book II

edit- Let us not forget what befits our present state in the pursuit of vain fancies. Mankind has its place in the sequence of things; childhood has its place in the sequence of human life; the man must be treated as a man and the child as a child. Give each his place, and keep him there. Control human passions according to man's nature; that is all we can do for his welfare. The rest depends on external forces, which are beyond our control.

- There is only one man who gets his own way—he who can get it single-handed; therefore freedom, not power, is the greatest good. That man is truly free who desires what he is able to perform, and does what he desires. This is my fundamental maxim. Apply it to childhood, and all the rules of education spring from it. Society has enfeebled man, not merely by robbing him of the right to his own strength, but still more by making his strength insufficient for his needs. This is why his desires increase in proportion to his weakness; and this is why the child is weaker than the man. If a man is strong and a child is weak it is not because the strength of the one is absolutely greater than the strength of the other, but because the one can naturally provide for himself and the other cannot. Thus the man will have more desires and the child more caprices, a word which means, I take it, desires which are not true needs, desires which can only be satisfied with the help of others.

Book III

edit- Our island is this earth; and the most striking object we behold is the sun. As soon as we pass beyond our immediate surroundings, one or both of these must meet our eye. Thus the philosophy of most savage races is mainly directed to imaginary divisions of the earth or to the divinity of the sun.

- As a general rule—never substitute the symbol for the thing signified, unless it is impossible to show the thing itself; for the child's attention is so taken up with the symbol that he will forget what it signifies.

- As soon as we have contrived to give our pupil an idea of the word "Useful," we have got an additional means of controlling him, for this word makes a great impression on him, provided that its meaning for him is a meaning relative to his own age, and provided he clearly sees its relation to his own well-being. This word makes no impression on your scholars because you have taken no pains to give it a meaning they can understand, and because other people always undertake to supply their needs so that they never require to think for themselves, and do not know what utility is. "What is the use of that?"

- At first our pupil had merely sensations, now he has ideas; he could only feel, now he reasons. For from the comparison of many successive or simultaneous sensations and the judgment arrived at with regard to them, there springs a sort of mixed or complex sensation which I call an idea. The way in which ideas are formed gives a character to the human mind. The mind which derives its ideas from real relations is thorough; the mind which relies on apparent relations is superficial. He who sees relations as they are has an exact mind; he who fails to estimate them aright has an inaccurate mind; he who concocts imaginary relations, which have no real existence, is a madman; he who does not perceive any relation at all is an imbecile. Clever men are distinguished from others by their greater or less aptitude for the comparison of ideas and the discovery of relations between them. Simple ideas consist merely of sensations compared one with another. Simple sensations involve judgments, as do the complex sensations which I call simple ideas. In the sensation the judgment is purely passive; it affirms that I feel what I feel. In the percept or idea the judgment is active; it connects, compares, it discriminates between relations not perceived by the senses. That is the whole difference; but it is a great difference. Nature never deceives us; we deceive ourselves.

Book IV

edit- The origin of our passions, the root and spring of all the rest, the only one which is born with man, which never leaves him as long as he lives, is self-love; this passion is primitive, instinctive, it precedes all the rest, which are in a sense only modifications of it. In this sense, if you like, they are all natural. But most of these modifications are the result of external influences, without which they would never occur, and such modifications, far from being advantageous to us, are harmful. They change the original purpose and work against its end; then it is that man finds himself outside nature and at strife with himself.

- Complete ignorance with regard to certain matters is perhaps the best thing for children; but let them learn very early what it is impossible to conceal from them permanently. Either their curiosity must never be aroused, or it must be satisfied before the age when it becomes a source of danger. Your conduct towards your pupil in this respect depends greatly on his individual circumstances, the society in which he moves, the position in which he may find himself, etc. Nothing must be left to chance; and if you are not sure of keeping him in ignorance of the difference between the sexes till he is sixteen, take care you teach him before he is ten.

Book V

edit- As a man's conduct is controlled by public fact, so is her religion ruled by authority. The daughter should follow her mother's religion, the wife her husband's. Were that religion false, the docility which leads mother and daughter to submit to nature's laws would blot out the sin of error in the sight of Goddess. Unable to judge for themselves they should accept the judgment of father and husband as that of the church. While men unaided cannot deduce the rules of their faith, neither can they assign limits to that faith by the evidence of reason; they allow themselves to be driven hither and thither by all sorts of external influences, they are ever above or below the truth. Extreme in everything, they are either altogether reckless or altogether pious; you never find them able to combine virtue and piety. Their natural exaggeration is not wholly to blame; the ill-regulated control exercised over them by men is partly responsible. Loose morals bring religion into contempt; the terrors of remorse make it a tyrant; this is why women have always too much or too little religion. As a woman's religion is controlled by authority it is more important to show her plainly what to believe than to explain the reasons for belief; for faith attached to ideas half-understood is the main source of fanaticism, and faith demanded on behalf of what is absurd leads to madness or unbelief. Whether our catechisms tend to produce impiety rather than fanaticism I cannot say, but I do know that they lead to one or other. In the first place, when you teach religion to little girls never make it gloomy or tiresome, never make it a task or a duty, and therefore never give them anything to learn by heart, not even their prayers. Be content to say your own prayers regularly in their presence, but do not compel them to join you. Let their prayers be short, as Christ himself has taught us. Let them always be said with becoming reverence and respect; remember that if we ask the Almighty to give heed to our words, we should at least give heed to what we mean to say.

- When you reached the age of reason, I secured you from the influence of human prejudice; when your heart awoke I preserved you from the sway of passion. Had I been able to prolong this inner tranquillity till your life's end, my work would have been secure, and you would have been as happy as man can be; but, my dear Emile, in vain did I dip you in the waters of Styx, I could not make you everywhere invulnerable; a fresh enemy has appeared, whom you have not yet learnt to conquer, and from whom I cannot save you. That enemy is yourself. Nature and fortune had left you free. You could face poverty, you could bear bodily pain; the sufferings of the heart were unknown to you; you were then dependent on nothing but your position as a human being; now you depend on all the ties you have formed for yourself; you have learnt to desire, and you are now the slave of your desires. Without any change in yourself, without any insult, any injury to yourself, what sorrows may attack your soul, what pains may you suffer without sickness, how many deaths may you die and yet live! A lie, an error, a suspicion, may plunge you in despair.

- It is a mistake to classify the passions as lawful and unlawful, so as to yield to the one and refuse the other. All alike are good if we are their masters; all alike are bad if we abandon ourselves to them. Nature forbids us to extend our relations beyond the limits of our strength; reason forbids us to want what we cannot get, conscience forbids us, not to be tempted, but to yield to temptation. To feel or not to feel a passion is beyond our control, but we can control ourselves. Every sentiment under our own control is lawful; those which control us are criminal. A man is not guilty if he loves his neighbour's wife, provided he keeps this unhappy passion under the control of the law of duty; he is guilty if he loves his own wife so greatly as to sacrifice everything to that love.

Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1765-1770; published 1782)

editBook I

edit- I have entered on an enterprise which is without precedent, and will have no imitator. I propose to show my fellows a man as nature made him, and this man shall be myself.

- I

- I know my heart, and have studied mankind; I am not made like any one I have been acquainted with, perhaps like no one in existence; if not better, I at least claim originality, and whether Nature did wisely in breaking the mould with which she formed me, can only be determined after having read this work.

- Variant translations: I may not be better than other people, but at least I am different.

If I am not better, at least I am different.

- Variant translations: I may not be better than other people, but at least I am different.

- Whenever the last trumpet shall sound, I will present myself before the sovereign judge with this book in my hand, and loudly proclaim, thus have I acted; these were my thoughts; such was I. With equal freedom and veracity have I related what was laudable or wicked, I have concealed no crimes, added no virtues; and if I have sometimes introduced superfluous ornament, it was merely to occupy a void occasioned by defect of memory: I may have supposed that certain, which I only knew to be probable, but have never asserted as truth, a conscious falsehood. Such as I was, I have declared myself; sometimes vile and despicable, at others, virtuous, generous and sublime; even as thou hast read my inmost soul: Power eternal! assemble round thy throne an innumerable throng of my fellow-mortals, let them listen to my confessions, let them blush at my depravity, let them tremble at my sufferings; let each in his turn expose with equal sincerity the failings, the wanderings of his heart, and, if he dare, aver, I was better than that man.

- Variant translation: Let the trumpet of the day of judgment sound when it will, I shall appear with this book in my hand before the Sovereign Judge, and cry with a loud voice, This is my work, there were my thoughts, and thus was I. I have freely told both the good and the bad, have hid nothing wicked, added nothing good.

- J'adore la liberté; j'abhorre la gêne, la peine, l'assujettissement. Tant que dure l'argent que j'ai dans ma bourse, il assure mon indépendance; il me dispense de m'intriguer pour en trouver d'autre, nécessité que j'eus toujours en horreur; mais de peur de le voir finir, je le choie. L'argent qu'on possède est l'instrument de la liberté; celui qu'on pourchasse est celui de la servitude.

- I love liberty, and I loathe constraint, dependence, and all their kindred annoyances. As long as my purse contains money it secures my independence, and exempts me from the trouble of seeking other money, a trouble of which I have always had a perfect horror; and the dread of seeing the end of my independence, makes me proportionately unwilling to part with my money. The money that we possess is the instrument of liberty, that which we lack and strive to obtain is the instrument of slavery.

Books II-VI

edit- Le remords s'endort durant un destin prospère et s'aigrit dans l'adversité.

- Remorse sleeps during a prosperous period but wakes up in adversity.

- Variant translations: Remorse sleeps during prosperity but awakes bitter consciousness during adversity.

Remorse goes to sleep during a prosperous period and wakes up in adversity. - II

- It is too difficult to think nobly when one thinks only of earning a living.

- Variant translation: It is too difficult to think nobly when one only thinks to get a living.

- II

- Hatred, as well as love, renders its votaries credulous.

- V

- I remembered the way out suggested by a great princess when told that the peasants had no bread: "Well, let them eat cake".

- Variant: At length I recollected the thoughtless saying of a great princess, who, on being informed that the country people had no bread, replied, "Then let them eat cake!"

- This passage contains a statement Qu'ils mangent de la brioche that has usually come to be attributed to Marie Antoinette; this was written in 1766, when Marie Antoinette was 10 and still 4 years away from her marriage to Louis XVI of France, and is an account of events of 1740, before she was born. It also implies the phrase had been long known before that time.

- VI

On the musicians of the Ospedale della Pieta (book VII)

edit- An account of a visit to the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice.

- A kind of music far superior, in my opinion, to that of operas, and which in all Italy has not its equal, nor perhaps in the whole world, is that of the 'scuole'. The 'scuole' are houses of charity, established for the education of young girls without fortune, to whom the republic afterwards gives a portion either in marriage or for the cloister. Amongst talents cultivated in these young girls, music is in the first rank. Every Sunday at the church of each of the four 'scuole', during vespers, motettos or anthems with full choruses, accompanied by a great orchestra, and composed and directed by the best masters in Italy, are sung in the galleries by girls only; not one of whom is more than twenty years of age. I have not an idea of anything so voluptuous and affecting as this music; the richness of the art, the exquisite taste of the vocal part, the excellence of the voices, the justness of the execution, everything in these delightful concerts concurs to produce an impression which certainly is not the mode, but from which I am of opinion no heart is secure. Carrio and I never failed being present at these vespers of the 'Mendicanti', and we were not alone. The church was always full of the lovers of the art, and even the actors of the opera came there to form their tastes after these excellent models. What vexed me was the iron grate, which suffered nothing to escape but sounds, and concealed from me the angels of which they were worthy. I talked of nothing else. One day I spoke of it at Le Blond's; "If you are so desirous," said he, "to see those little girls, it will be an easy matter to satisfy your wishes. I am one of the administrators of the house, I will give you a collation [light meal] with them." I did not let him rest until he had fulfilled his promise. In entering the saloon, which contained these beauties I so much sighed to see, I felt a trembling of love which I had never before experienced. M. le Blond presented to me one after the other, these celebrated female singers, of whom the names and voices were all with which I was acquainted. Come, Sophia, — she was horrid. Come, Cattina, — she had but one eye. Come, Bettina, — the small-pox had entirely disfigured her. Scarcely one of them was without some striking defect.

Le Blond laughed at my surprise; however, two or three of them appeared tolerable; these never sung but in the choruses; I was almost in despair. During the collation we endeavored to excite them, and they soon became enlivened; ugliness does not exclude the graces, and I found they possessed them. I said to myself, they cannot sing in this manner without intelligence and sensibility, they must have both; in fine, my manner of seeing them changed to such a degree that I left the house almost in love with each of these ugly faces. I had scarcely courage enough to return to vespers. But after having seen the girls, the danger was lessened. I still found their singing delightful; and their voices so much embellished their persons that, in spite of my eyes, I obstinately continued to think them beautiful.

Books VIII-XII

edit- The thirst after happiness is never extinguished in the heart of man.

- IX

- He thinks like a philosopher, but governs like a king.

- Of Frederick the Great

- XII

Dialogues: Rousseau Judge of Jean-Jacques (published 1782)

edit- What I had to say was so clear and I felt it so deeply that I am amazed by the tediousness, repetitiousness, verbiage, and disorder of this writing. What would have made it lively and vehement coming from another's pen is precisely what has made it dull and slack coming from mine. The subject was myself, and I no longer found on my own interest that zeal and vigor of courage which can exalt a generous soul only for another person's cause.

- On the Subject and Form of This Writing; translated by Judith R. Bush, Christopher Kelly, Roger D. Masters

- There as here, passions are the motive of all action, but they are livelier, more ardent, or merely simpler and purer, thereby assuming a totally different character. All the first movements of nature are good and right.

- First Dialogue; translated by Judith R. Bush, Christopher Kelly, Roger D. Masters

- Beings who are so uniquely constituted must necessarily express themselves in other ways than ordinary men. It is impossible that with souls so differently modified, they should not carry over into the expression of their feelings and ideas the stamp of those modifications.

- First Dialogue; translated by Judith R. Bush, Christopher Kelly, Roger D. Masters

- As for the Soothsayer, although I am certain no one feels the true beauties of that work better than I, I am far from finding these beauties in the same places as the infatuated public does. They are not the products of study and knowledge, but rather are inspired by taste and sensitivity.

- First Dialogue; translated by Judith R. Bush, Christopher Kelly, Roger D. Masters

- I want you to read the true system of the heart, drafted by a decent man and published under another name. I do not want you to be biased against good and useful books merely because a man unworthy of reading them has the audacity to call himself the Author.

- First Dialogue; translated by Judith R. Bush, Christopher Kelly, Roger D. Masters

- Through the fortunate effect of my frankness, I had the rarest and surest opportunity to know a man well, which is to study him at leisure in his private life and living, so to speak, with himself. For he share himself without reservation and made me feel as much at home in his house as in mine. I had almost no other abode than his own.

- Second Dialogue; translated by Judith R. Bush, Christopher Kelly, Roger D. Masters

- Much more naturally than you do: because flight is a much more natural consequence of fear than of hate. He doesn't flee men because he hates them, but because he is afraid of them. He doesn't flee them in order to harm them, but to try o escape the harm they wish to do to him. They, on the contrary, don't seek him through friendship, but through hate. They seek him and he flees from them just as in the wilderness of Africa, where there are few men and many tigers, the men flee the tigers, the men flee the tigers, and the tigers seek the men.

- Second Dialogue; translated by Judith R. Bush, Christopher Kelly, Roger D. Masters

- Let's not be dazzled by the sententious glitter with which error and lying often cover themselves. Society is not created by the crowd, and bodies come together in vain when hearts reject each other. The truly sociable man is more difficult in his relationships than others; those which consist only in false appearances cannot suit him. He prefers to live far from wicked men without thinking about them, than to see them and hate them. He prefers to flee his enemy rather than seek him out to harm him. A person who knows no other society than that of the heart will not seek his society in your circles. That is How J.J. must have thought and behaved before the conspiracy of which he is the object.

- Second Dialogue; translated by Judith R. Bush, Christopher Kelly, Roger D. Masters

- It is unfortunate for J.J that Rousseau cannot say everything he knows about him.

- Second Dialogue; translated by Judith R. Bush, Christopher Kelly, Roger D. Masters

- Sensitivity is the principle of all action. A being, albeit animated, who would feel nothing, would never act, for what would its motive for acting be? God himself is sensitive since he acts. All men are therefore sensitive, and perhaps to the same degree, but not in the same manner. There is a purely passive physical and organic sensitivity which seems to have as its end only the preservation of our bodies and of our species through the direction of pleasure and pain. There is another sensitivity that I call active and moral which is nothing other than the faculty of attaching our affections to beings who are foreign to us. This type, about which study of nerve pairs teaches nothing, seems to offer a fairly clear analogy for souls to the magnetic faculty of bodies. Its strength is in proportion to the relationships we feel between ourselves and other beings, and depending on the nature of these relationships it sometimes acts positively by attraction, sometimes negatively by repulsion, like the poles of a magnet. The positive or attracting action is the simple work of nature, which seeks to extend and reinforce the feeling of our being; the negative or repelling action, which compresses and diminishes the being of another, is a combination produced by reflection. From the former arise all the loving and gentle passions, and from the latter all the hateful and cruel passions.

- Second Dialogue; translated by Judith R. Bush, Christopher Kelly, Roger D. Masters

- He neither seeks nor avoids talking about his enemies. When he does speak of them, it is with pride without disdain, humor without rancor, reproach without bitterness, frankness without spite. And in the same way, he speaks of his rivals for glory only with deserved praises that conceal no hidden venom, which can certainly not be said of the praise they sometimes give him. But what I find in him that is most rare in an Author and and even in a sensitive man is the most perfect tolerance in matters of feelings and opinions, and the putting aside of all partisan spirit, even in his own favor; wanting freely to state his opinion and his reasons when the issue demands it, and even doing so with passion when his heart is agitated; but not blaming people for not adopting what he feels any more than he puts up with anyone's wish to deprive him of his feeling; and giving everyone the same freedom of thought as he insists on having for himself. I hear everyone talk about tolerance, but he is the only truly tolerant person I have known.

- Second Dialogue; translated by Judith R. Bush, Christopher Kelly, Roger D. Masters

- J.J. did not always flee from men, but he has always loved solitude. He enjoyed himself with the friends he velieved he had, but he enjoyed himself still more alone. He valued their society, but he sometimes needed to withdraw, and he would perhaps have preferred to live always alone than always with them.

- Second Dialogue; translated by Judith R. Bush, Christopher Kelly, Roger D. Masters

- Oh providence! Oh nature! Treasure of the poor, resource of the unfortunate. The person who feels, knows your holy laws and trusts them, the person whose heart is at peace and whose body does not suffer, thanks to you is not entirely prey to adversity.

- Second Dialogue; translated by Judith R. Bush, Christopher Kelly, Roger D. Masters

- Visions are a feeble resource, you will say, against great adversity! Oh Sir, these visions may possibly have more reality than all those apparent goods about which men make so much ado, for they never bring a true feeling of happiness to the soul, and those who possess them are equally forced to project themselves into the future for want of finding enjoyments that satisfy them, in the present.

- Second Dialogue; translated by Judith R. Bush, Christopher Kelly, Roger D. Masters

Quotes about Rousseau

edit- Quotes are arranged alphabetical per author

A - F

edit- ...whatever his ambiguities of his legacy in respect of totalitarianism, there is no doubt that Rousseau is the key figure in the development of democratic thought...it was Rousseau who developed the concept of sovereignty of the people, and he was the first to insist upon the fitness and right of the ordinary people to participate in the political system as full citizens.

- Ian Adams and R. W. Dyson, Fifty Major Political Thinkers, Routledge, 2003.

- Binary distinctions are not necessarily motivated by a desire to dominate. David Spurr (1993: 103) discusses the ways in which Rousseau, in the Essay on the Origin of Languages, attempts to validate the ‘life and warmth’ of Oriental languages such as Arabic and Persian. But in employing the ‘logic and precision’ of Western writing to do so, Rousseau effectively negates these languages because they become characterized by a primitive lack of rational order and culture. Although setting out to applaud such languages, he succeeds in confirming the binary between European science, understanding, industry and writing on the one hand, and Oriental primitivism and irrationality on the other.

- Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, Helen Tiffin (2000). Post-Colonial Studies: The Key Concepts, second edition, London: Routledge, p. 20, citing Spurr's The Rhetoric of Empire: Colonial Discourse in Journalism, Travel Writing and Imperial Administration, Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- It seems to me imperative to re-establish the true dualism—that between vital impulse and vital control—and to this end to affirm the higher will first of all as a psychological fact. The individual needs, however, to go beyond this fact if he is to decide how far he is to exercise control in any particular instance with a primary view to his own happiness: in short, he needs standards. To secure standards, at least critically, he cannot afford, like the Rousseauist, to disparage the intellect.

- Irving Babbitt, "What I Believe" (1930), Irving Babbitt: Representative Writings (1981), pp. 14-15

- The average age at which a man marries is thirty years; the average age at which his passions, his most violent desires for genesial delight are developed, is twenty years. Now during the ten fairest years of his life, during the green season in which his beauty, his youth and his wit make him more dangerous to husbands than at any other epoch of his life, his finds himself without any means of satisfying legitimately that irresistible craving for love which burns in his whole nature. During this time, representing the sixth part of human life, we are obliged to admit that the sixth part or less of our total male population and the sixth part which is the most vigorous is placed in a position which is perpetually exhausting for them, and dangerous for society.

“Why don’t they get married?” cries a religious woman.

But what father of good sense would wish his son to be married at twenty years of age?

Is not the danger of these precocious unions apparent at all? It would seem as if marriage was a state very much at variance with natural habitude, seeing that it requires a special ripeness of judgment in those who conform to it. All the world knows what Rousseau said: “There must always be a period of libertinage in life either in one state or another. It is an evil leaven which sooner or later ferments.”

Now what mother of a family is there who would expose her daughter to the risk of this fermentation when it has not yet taken place?- Honore de Balzac (1829) The Physiology of Marriage; or, the Musings of an Eclectic Philosopher on the Happiness and Unhappiness of Married Life “Meditation IV: On the Virtuous Woman”

- Rousseau's unforgivable crime was his rejection of the graces and luxuries of civilized existence. Voltaire had sung “The superfluous, that most necessary thing." For the high bourgeois standard of living Rousseau would substitute the middling peasant's. It was the country versus the city – an exasperating idea for them, as was the amazing fact that every new work of Rousseau's was a huge success, whether the subject was politics, theater, education, religion, or a novel about love.

- Jacques Barzun, From Dawn to Decadence (2001).

- ...As with any truly great writer, it is foolish to judge Rousseau by the instances where people tried to follow his advice literally, still less by the harmful things done in his name (by which standard Jesus Christ does not exactly come off unblemished.) Rousseau's influence on modern culture has been far too vast and multifaceted to squeeze into reductive categories of “positive” and “negative” and even his most misguided prescriptions often came accompanied by profound and poetic insights.

- David A. Bell, "Happy Birthday to Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Why the World’s First Celebrity Intellectual Still Matters",New Republic, June 22nd, 2012.

- Hence Rousseau's novelistic works, Emile, La Nouvelle Héloïse, and Confessions―each of which is much longer than his primary political treatise, the two Discourses and the Social Contract, put together―constitute an attempt to establish what was missing in earlier democratic thinkers, a democratic art. He does for democracy what Socrates did for aristocracy in the Republic.

- Allan Bloom, "Rousseau on Equality of the Sexes" in Justice And Equality Here and Now, ed. Frank S. Lucash (1986)

- For Rousseau, man's nature is essentially good, but he was corrupted by various “advances” in human civilization (especially the institution of private property). Although man's natural “innocence” has been lost, Rousseau thought that it could be replaced by a new form of moral goodness through the establishment of new political institutions. When we compare this to St. Augustine, we can see what a departure this is from the mainstream of Pauline Christianity. Augustine held that man is inescapably sinful and concludes that, as such, the City of God cannot be achieved on earth. Rousseau's major contribution to the foundation of socialist thought is in his rejection of human sinfulness and his commitment to human improvement through institutional change. With this foundational belief, he set the stage for perfectionist political doctrines that moved focus from “the next world” of Christianity by arguing that this world can be transformed into “heaven on earth.”

- Nicholas Buccola, “‘The Tyranny of the Least and the Dumbest’: Nietzsche's Critique of Socialism,” Quarterly Journal of Ideology, Volume 31, 2009, 3 &4, italics as in original

- The assembly [in revolutionary France] recommends to its youth a study of the bold experimenters in morality. Everybody knows that there is a great dispute amongst their leaders, which of them is the best resemblance of Rousseau. In truth, they all resemble him. His blood they transfuse into their minds and into their manners. Him they study; him they meditate; him they turn over in all the time they can spare from the laborious mischief of the day, or the debauches of the night. Rousseau is their canon of holy writ; in his life he is their canon of Polycletus; he is their standard figure of perfection. To this man and this writer, as a pattern to authors and to Frenchmen, the foundries of Paris are now running for statues, with the kettles of their poor and the bells of their churches. If an author had written like a great genius on geometry, though his practical and speculative morals were vicious in the extreme, it might appear, that in voting the statue, they honoured only the geometrician. But Rousseau is a moralist, or he is nothing. It is impossible, therefore, putting the circumstances together, to mistake their design in choosing the author with whom they have begun to recommend a course of studies.

- Rousseau, though holding views diametrically opposed to Luther's as to the character of man, finally strengthened his hand by his estimate of man's mind. Luther believed in the utter moral wretchedness of man, but Rousseau believed not only in man's goodness on the plane of character but he also was convinced (like Luther) that man is by nature intelligent. The "democrats" of the late eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries deducted from Luther's and Rousseau's joint declaration that man is intelligent (either by nature or by an inner light) the further conclusion that the sum total of all minds must be perfection itself.

- Francis Stuart Campbell, pen name of Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn (1943), Menace of the Herd, or, Procrustes at Large, Milwaukee, WI: The Bruce Publishing Company, p. 41

- National Socialism is the fulfillment of Continental "liberalism" which stems largely from Rousseau [...] The continental Liberals never were liberals in the English sense [i.e., never were classical liberals ]; their "liberalism" was nothing else but the struggle against the existing order and the old tradition. Foolishly enough the English Liberals supported their continental "coreligionists," never being fully aware of the abyss which actually divided them.

- Francis Stuart Campbell, pen name of Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn (1943), Menace of the Herd, or, Procrustes at Large, Milwaukee, WI: The Bruce Publishing Company, p. 213

- If the author of the romantic creed was Rousseau, its popularizer and vulgarizer was George Sand.

- E. H. Carr, attributed in Luisa Capetillo, Pioneer Puerto Rican Feminist, Norma Valle-Ferrer

- Jean Jacques Rousseau's many false starts as medical student, clockmaker, theologian, painter, servant, musician, and botanist are noted, as well as his curious letter addressed to God Almighty which he placed under the altar of Notre Dame. Rousseau's expressed repugnance toward the normal sex act is also noted.

- Hervey Cleckley, on Rousseau's erratic and unusual behavior as possibly consistent with a diagnosis of psychopathy, in The Mask of Sanity (1941; fifth edition 1976), ISBN 0-9621519-0-4

- Above all, Rousseau is the explorer of that dark continent, the modern self. It is no surprise that he wrote one of the most magnificent autobiographies of all time, his Confessions. Personal experience starts to take on a significance it never had for Plato or Descartes. What matters now is less objective truth than truth-to-self – a passionate conviction that one's identity is uniquely precious, and that expressing it as freely and richly as possible is a sacred duty. In this belief, Rousseau is a forerunner not only of the Romantics, but of the liberals, existentialists and spiritual individualists of modern times.

- Terry Eagleton, "What would Rousseau make of our selfish age?", The Guardian (June 27, 2012)

- His outlook was that of the petty-bourgeois peasant, clinging to his hard-won independence in the face of power and privilege. He sometimes writes as though any form of dependence on others is despicable. Yet he was a radical egalitarian in an age when such thinkers were hard to find. Almost uniquely for his age, he also believed in the absolute sovereignty of the people. To bow to a law one did not have a hand in creating was a recipe for tyranny. Self-determination lay at the root of all ethics and politics. Human beings might misuse their freedom, but they were not truly human without it.

- Terry Eagleton, "What would Rousseau make of our selfish age?", The Guardian (June 27, 2012)

G - L

edit- Now, you needn't have studied marketing to know that there are two groups of people who can always be convinced to consume more than they need to: addicts and children. School has done a pretty good job of turning our children into addicts, but a spectacular job of turning our children into children. Again, this is no accident. Theorists from Plato to Rousseau to our own Dr. [Alexander] Inglis knew that if children could be cloistered with other children, stripped of responsibility and independence, encouraged to develop only the trivializing emotions of greed, envy, jealousy, and fear, they would grow older but never truly grow up.

- John Taylor Gatto (2009), Weapons of Mass Instruction: A Schoolteacher's Journey Through the Dark World of Compulsory Schooling, p. xxi

- [W]hat truly makes the French Revolution the first fascist revolution was its effort to turn politics into a religion. (In this the revolutionaries were inspired by Rousseau, whose concept of the general will divinized the people while rendering the person an afterthought.)

- Jonah Goldberg (2007). Liberal Fascism: The Secret History of the American Left from Mussolini to the Politics of Meaning. NY: Doubleday, ISBN 9780385511841, p. 13

- Robespierre’s ideas were derived from his close study of Rousseau, whose theory of the general will formed the intellectual basis for all modern totalitarianisms. According to Rousseau, individuals who live in accordance with the general will are “free” and “virtuous” while those who defy it are criminals, fools or heretics. Those enemies of the common good must be forced to bend to the general will. He described this state-sanctioned coercion in Orwellian terms as the act of “forcing men to be free.” It was Rousseau who originally sanctified the sovereign will of the masses while dismissing the mechanisms of democracy as corrupting and profane. Such mechanics -- voting in elections, representative bodies, and so forth -- are “hardly ever necessary where the government is well-intentioned,” wrote Rousseau in a revealing turn of phrase.

- Jonah Goldberg (2007). Liberal Fascism: The Secret History of the American Left from Mussolini to the Politics of Meaning. NY: Doubleday, ISBN 9780385511841, p. 39

- Marx, like Rousseau before him, believed that men are good and made bad only by bad social systems. Unlike Rousseau, he believed that these systems arise from historical necessity. It occurred neither to Marx nor to Rousseau-as it did to Madison-that bad men corrupt good systems just as often as vice versa.

- Ernest Van Den Haag, “Marxism as Pseudo-Science,” Reason Papers No. 12 (Spring 1987) pp. 26-32.

- This peculiar thinker - although often described as irrationalist or romantic - also latched on to and deeply depended on Cartesian thought. Rousseau's heady brew of ideas came to dominate 'progressive' thought, and led people to forget that freedom as a political institution had arisen not by human beings 'striving for freedom' in the sense of release from restraints, but by their striving for the protection of a known secure individual domain. Rousseau led people to forget that rules of conduct necessarily constrain and that order is their product; and that these rules, precisely by limiting the range of means that each individual may use for his purposes, greatly extend the range of ends each can successfully pursue.

It was Rousseau who - declaring in the opening statement of The Social Contract that 'man was born free, and he is everywhere in chains', and wanting to free men from all 'artificial' restraints - made what had been called the savage the virtual hero of progressive intellectuals, urged people to shake off the very restraints to which they owed their productivity and numbers, and produced a conception of liberty that became the greatest obstacle to its attainment. (...) The admittedly great seductive appeal of this view hardly owes its power (whatever it may claim) to reason and evidence. (...) Despite these contradictions, there is no doubt that Rousseau's outcry was effective or that, during the past two centuries, it has shaken our civilisation. Moreover, irrationalist as it is, it nonetheless did appeal precisely to progressivists by its Cartesian insinuation that we might use reason to obtain and justify direct gratification of our natural instincts.- Friedrich Hayek, The Fatal Conceit (1988), Ch. 4: The Revolt of Instinct and Reason

- The first great frontal assault on the Enlightenment was launched by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). Rousseau has a well-deserved reputation as the bad boy of eighteenth century French philosophy. In the context of Enlightenment intellectual culture, Rousseau's was a major dissenting voice. He was an admirer of all things Spartan—the Sparta of militaristic and feudal communalism—and a despiser of all things Athenian—the classical Athens of commerce, cosmopolitanism, and the high arts. Civilization is thoroughly corrupting, Rousseau argued -- not only the oppressive feudal system of eighteenth-century France with its decadent and parasitical aristocracy, but also its Enlightenment alternative with its exaltation of reason, property, the arts and sciences. Name a dominant feature of the Enlightenment, and Rousseau was against it.

- Philosopher Stephen Hicks, Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault (2004), Tempe, AZ: Scholargy Press, p. 92.

- Thus you see, [Rousseau] is a Composition of Whim, Affectation, Wickedness, Vanity, and Inquietude, with a very small, if any Ingredient of Madness. ... The ruling Qualities abovementioned, together with Ingratitude, Ferocity, and Lying, I need not mention, Eloquence and Invention, form the whole of the Composition.

- Philosopher David Hume, letter to economist Adam Smith, dated October 8, 1767 [2]

- Rousseau and his disciples were resolved to force men to be free; in most of the world, they triumphed; men are set free from family, church, town, class, guild; yet they wear, instead, the chains of the state, and they expire of ennui or stifling lone lines.

- Russell Kirk, The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Eliot (1953)

- In the famous fragment on the origin of inequality, Rousseau seems to believe that private property was simply invented by a madman; yet we do not know how this diabolical contrivance, opposed as it was to innate human drives, was taken up by other people and spread all over the human societies.

- A utopian vision, once it is translated into political idiom, becomes mendacious or self-contradictory; it provides new names for old injustice or hides the contradictions under ad hoc invented labels. This is especially true of revolutionary utopias, whether elaborated in the actual revolutionary process or simply applied in its course. The Orwellian language had been known, though not codified, long before modern totalitarian despotism. Rousseau's famous slogan, “One has to compel people to freedom,” is a good example.

- You can lock the door upon them, but they burst open their shaky lattices and call out over the house-tops so that men cannot but hear. You hounded wild Rousseau into the meanest garret of the Rue St. Jacques and jeered at his angry shrieks. But the thin, piping tones swelled a hundred years later into the sullen roar of the French Revolution, and civilization to this day is quivering to the reverberations of his voice.

- Rousseau, that subtle Diogenes.

- Immanuel Kant, Lectures on Ethics, trans. Peter Heath, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 45

M - R

edit- The sentiment that dominates all Rousseau’s works is a certain plebeian anger that excites him against every kind of superiority. The energetic submission of the wise man bends nobly under the indispensable empire of social distinctions, and never does be appear greater than when he bows; but Rousseau has nothing at all of this loftiness. Weak and surly, he spent his life spouting insults to the great, as he would have offered the same to the people if he had been born a great lord.

- His character explains his political heresies; it is not the truth that inspires him, it is ill humour. Whenever he sees greatness and especially hereditary greatness, he fumes and loses his faculty of reason; this happens to him especially when he is talking about aristocratic government.

- Joseph de Maistre, Against Rousseau (1795), p. 138

- In truth, Rousseau was a genius whose real influence cannot be traced with precision because it pervaded all the thought that followed him...Men will always be sharply divided about Rousseau: for he released imagination as well as sentimentalism; he increased men's desire for justice as well as confusing their minds, and he gave the poor hope even though the rich could make use of his arguments.

- Kingsley Martin, French Liberal Thought in the Eighteenth Century (1962).

- In one direction at least Rousseau's influence was a steady one: he discredited force as a basis for the State, convinced men that authority was legitimate only when founded in rational consent and that no arguments from passing expediency could justify a government in disregarding individual freedom or in failing to promote social equality.

- Kingsley Martin, French Liberal Thought in the Eighteenth Century (1962).

- It is not enough to say that Jean-Jacques is close to us; he is one of us. His contemporaries and the generation that followed his have retained his redundancy and his eloquence.

- François Mauriac, Men I hold Great, Kennikat Press, 1971.

- [M]y position has nothing in common with a Rousseauistic optimism about human "nature.” [...] Rousseau's pedagogy is profoundly manipulative. This does not always seem to be recognized by educators, but it has been convincingly demonstrated and documented.

- Alice Miller (1972) on Rousseau's educational philosophy as an exemplar of “poisonous pedagogy”, in For Your Own Good: Hidden Cruelty in Child-rearing and the Roots of Violence

- The disciples of Jean Jacques Rousseau who raved about nature and the blissful condition of man in the state of nature did not take notice of the fact that the means of subsistence are scarce and that the natural state of man is extreme poverty and insecurity.

- Ludwig von Mises, Theory and History: An Interpretation of Social and Economic Revolution (1957), p. 173

- Thus, in the eighteenth century, when nearly all the instructed, and all those of the uninstructed who were led by them, were lost in admiration of what is called civilisation, and of the marvels of modern science, literature, and philosophy, and while greatly overrating the amount of unlikeness between the men of modern and those of ancient times, indulged the belief that the whole of the difference was in their own favour; with what a salutary shock did the paradoxes of Rousseau explode like bombshells in the midst, dislocating the compact mass of one-sided opinion, and forcing its elements to recombine in a better form and with additional ingredients. Not that the current opinions were on the whole farther from the truth than Rousseau's were; on the contrary, they were nearer to it; they contained more of positive truth, and very much less of error. Nevertheless there lay in Rousseau's doctrine, and has floated down the stream of opinion along with it, a considerable amount of exactly those truths which the popular opinion wanted; and these are the deposit which was left behind when the flood subsided. The superior worth of simplicity of life, the enervating and demoralising effect of the trammels and hypocrisies of artificial society, are ideas which have never been entirely absent from cultivated minds since Rousseau wrote; and they will in time produce their due effect, though at present needing to be asserted as much as ever, and to be asserted by deeds, for words, on this subject, have nearly exhausted their power.

- John Stuart Mill, On liberty (1859).

- But Rousseau — to what did he really want to return? Rousseau, this first modern man, idealist and rabble in one person — one who needed moral "dignity" to be able to stand his own sight, sick with unbridled vanity and unbridled self-contempt. This miscarriage, couched on the threshold of modern times, also wanted a "return to nature"; to ask this once more, to what did Rousseau want to return? I still hate Rousseau in the French Revolution: it is the world-historical expression of this duality of idealist and rabble. The bloody farce which became an aspect of the Revolution, its "immorality," is of little concern to me: what I hate is its Rousseauan morality — the so-called "truths" of the Revolution through which it still works and attracts everything shallow and mediocre. The doctrine of equality! There is no more poisonous poison anywhere: for it seems to be preached by justice itself, whereas it really is the termination of justice. "Equal to the equal, unequal to the unequal" — that would be the true slogan of justice; and also its corollary: "Never make equal what is unequal." That this doctrine of equality was surrounded by such gruesome and bloody events, that has given this "modern idea" par excellence a kind of glory and fiery aura so that the Revolution as a spectacle has seduced even the noblest spirits.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols (1889), translator Walter Kauffman

- I remember once lately discussing with a friend the instance of some one we knew who had become bored with existence and had taken his own way out of it. I said I could not object to suicide on the ethical or religious grounds ordinarily alleged, and I saw nothing but uncommonly far-fetched absurdity in Rousseau's plea that suicide is a robbery committed against society.

- Albert Jay Nock (1943), Memoirs of a Superflous Man, NY: Harper and Brothers, p. 326

- Sexuality and eroticism are the intricate intersection of nature and culture. Feminists grossly oversimplify the problem of sex when they reduce it a matter of social convention: readjust society, eliminate sexual inequality, purify sex roles, and happiness and harmony will reign. Here feminism, like all liberal movements of the past two hundred years, is heir to Rousseau.

- Camille Paglia, Sexual Personae (1990), p. 1.

- We remain in the Romantic cycle initiated by Rousseau: liberal idealism canceled by violence, barbarism, disillusionment and cynicism.

- Camille Paglia, Sexual Personae (1990), p. 232.

- [F]ascism owed something to the Enlightenment idea that society need not be determined by tradition, but could be organized according to a blueprint derived from universal principles. The Enlightenment thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau's notion that society should be governed by one such universal ideal, the ‘general will’, is especially relevant, since it was taken up by the most revolutionary of the French Revolutionaries, the Jacobins. The Jacobins justified violence as a means to construct a new order and weed out those who opposed the general will (or the nation). They were ready to force people to be free.

- Kevin Passamore, Fascism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280155-4, p. 34

- If we prefer to trace a lineage [of fascist ideology] within the [political] Left, drawing on the Enlightenment's own perception that individual liberty can undermine community, some have gone back as far as Rousseau.

- Robert O. Paxton, "Five Stages of Fascism." The Journal of Modern History, Vol 70 no. 1 (March, 1998).

- This fact is that Rousseau who set the Western world aflame with the doctrine of equality and democracy for men also formulated and put into circulation a doctrine claiming that woman should be content to please man and get very little in return…Rousseau's doctrine that woman's duty is to please man fitted neatly, not only with Rousseau's personal egotism but also into the genteel theory respecting woman which was then spreading among the middle classes in England.

- Mary Ritter Beard, Woman as force in history (1946)

- At the present time, Hitler is an outcome of Rousseau; Roosevelt and Churchill, that of Locke.

- Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1945, p. 685.

- Liberty is the nominal goal of Rousseau's thought, but in fact it is equality that he values, and he seeks to secure even at the expense of liberty.

- Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy

S - Z

edit- It was not until after the age of Rousseau, from which must be dated the great humanitarian movement of the past century, that Vegetarianism began to assert itself as a system, a reasoned plea for the disuse of flesh-food.

- Henry S. Salt, The Humanities of Diet (1897), Manchester: The Vegetarian Society, 1914.

- On the other hand, my basis is supported by the authority of the greatest moralist of modern times; for such, undoubtedly, J. J. Rousseau is,—that profound reader of the human heart, who drew his wisdom not from books, but from life, and intended his doctrine not for the professorial chair, but for humanity; he, the foe of all prejudice, the foster-child of nature, whom alone she endowed with the gift of being able to moralise without tediousness, because he hit the truth and stirred the heart.

- Arthur Schopenhauer, On the Basis of Morality (1840), trans. Arthur Brodrick Bullock, London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1903, Part III, ch. VIII, 9, p. 230.

- Although neither Marx nor Engels wrote much on Rousseau, the imprint of his way of thinking is unmistakable. Rousseau's politics were fundamentally anti-political and authoritarian even while he looked forward to the ultimate era of universal harmony. Not without reason he is seen as an intellectual progenitor of twentieth-century totalitarianism.

- Robert Service, Comrades! A History of World Communism (2007), p. 21

- J.-J. Rousseau, répondit-il, n'est à mes yeux qu'un sot, lorsqu'il s'avise de juger le grand monde; il ne le comprenait pas, et y portait le cœur d'un laquais parvenu... Tout en prêchant la république et le renversement des dignités monarchiques, ce parvenu est ivre de bonheur, si un duc change la direction de sa promenade après dîner, pour accompagner un de ses amis.

- "Jean Jacques Rousseau," he answered, "is nothing but a fool in my eyes when he takes it upon himself to criticise society; he did not understand it, and approached it with the heart of an upstart flunkey.... For all his preaching a Republic and the overthrow of monarchical titles, the upstart is mad with joy if a Duke alters the course of his after-dinner stroll to accompany one of his friends."

- Stendhal Le Rouge et le Noir (The Red and the Black) (1830) Vol. II, ch. VIII

- [A] lucid journal of a life so utterly degraded that it has been a bestseller in France ever since.

- Hugh Trevor-Roper on Rousseau's Confessions, as quoted in Joseph Epstein (2012), Essays in Biography, Axios Press

- In Rousseau's account of the means by which equality was lost, the incoming of the ideas of property is prominent. From property arose civil society. With property came in inequality. His exposition of inequality is confused, and it is not possible always to tell whether he means inequality of possessions or of political rights.

- Equality by Charles Dudley Warner

- Kant’s moral outlook is also fundamentally determined by a subtle, shrewd, historically self-conscious (and characteristically Enlightenment) conception of human nature and human psychology that most treatments of Kantian ethics (even sympathetic ones) have largely overlooked. This side of Kant owes a great deal to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and it belongs to a radical tradition in the social criticism of modernity whose later representatives include Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Karl Marx. The Kantian mistrust of our empirical desires reflects a Rousseauian picture of the way our natural desires have been influenced by the loss of innocence – the restless competitiveness – characteristic of human beings in the social condition, especially as found in the social inequalities of what Rousseau and Kant called the “civilized” stage of human society but was later renamed “modern bourgeois society” or “capitalism.” Again, to miss this continuity is not only to misread Kant; it is badly to misread the history, and even the living reality, of the social order that is all around us.

- Allen W. Wood, Kantian Ethics (2008), Ch. 1. Reason

External links

edit- Mondo Politico Library's presentation of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's book, The Social Contract (G.D.H. Cole translation; full text; formatted for easy on-screen reading)

- Espace Rousseau, a museum located at 40 Rue Grand-Rue, Geneva, Rousseau's birthplace

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Philosopher

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- The European Enlightenment: Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- Savage or Solitary? The Wild Man and Rousseau's Man of nature, an article by Nancy Yousef comparing Rousseau's theoretical account with the reality of Victor of Aveyron

Online texts

edit- Rousseau texts in French

- 'Elementary Letters on Botany', 1771-3

- A Discourse on the Moral Effects of the Arts and Sciences

- Narcissus, or The Self-Admirer: A Comedy

- Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men

- Discourse on Political Economy

- The Creed of a Savoyard Priest

- The Social Contract, Or Principles of Political Right

- Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- Constitutional Project for Corsica

- Considerations on the Government of Poland

Project Gutenberg texts:

- Free eBook of The Confessions of Jean-Jaques Rousseau at Project Gutenberg

- Free eBook of Images from the Confessions of J. J. Rousseau at Project Gutenberg

- Free eBook of Widger's Quotations from Project Gutenberg Edition of Confessions of J. J. Rousseau at Project Gutenberg

- Free eBook of A Discourse Upon the Origin and the Foundation Of The Inequality Among Mankind at Project Gutenberg

- Free eBook of Emile at Project Gutenberg