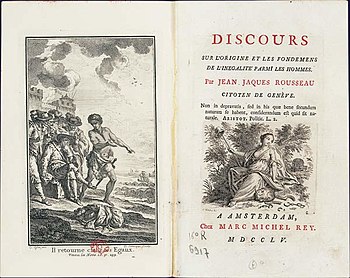

Discourse on Inequality

work by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (Discours sur l'origine et les fondements de l'inégalité parmi les hommes), also commonly known as the "Second Discourse", is a 1754 work by philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Quotes

edit- Also known as Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men and A Dissertation On the Origin and Foundation of the Inequality of Mankind. Translation by G. D. H. Cole online

- It appears, in fact, that if I am bound to do no injury to my fellow-creatures, this is less because they are rational than because they are sentient beings: and this quality, being common both to men and beasts, ought to entitle the latter at least to the privilege of not being wantonly ill-treated by the former.

- Preface

- Peoples once accustomed to masters are not in a condition to do without them. If they attempt to shake off the yoke they still more estrange themselves from freedom, as by mistaking for it an unbridled license to which it is diametrically opposed, they nearly always manage, by their revolutions, to hand themselves over to seducers, who only make their chains heavier than before.

- Preface

- Le premier qui, ayant enclos un terrain, s'avisa de dire: Ceci est à moi, et trouva des gens assez simples pour le croire, fut le vrai fondateur de la société civile. Que de crimes, de guerres, de meurtres, que de misères et d'horreurs n'eût point épargnés au genre humain celui qui, arrachant les pieux ou comblant le fossé, eût crié à ses semblables: Gardez-vous d'écouter cet imposteur; vous êtes perdus, si vous oubliez que les fruits sont à tous, et que la terre n'est à personne.

- The first man who, having enclosed a piece of ground, bethought himself of saying This is mine, and found people simple enough to believe him, was the real founder of civil society. From how many crimes, wars, and murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes might not any one have saved mankind, by pulling up the stakes, or filling up the ditch, and crying to his fellows: Beware of listening to this impostor; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.

- Part II. Variant translation: The first man who, having fenced in a piece of land, said "This is mine," and found people naive enough to believe him, that man was the true founder of civil society.

- Never exceed your rights, and they will soon become unlimited.

- Money is the seed of money, and the first guinea is sometimes more difficult to acquire than the second million.

- [D]emandant toujours aux autres ce que nous sommes et n'osant jamais nous interroger là-dessus nous-mêmes...

- We are reduced to asking others what we are. We never dare to ask ourselves.

- Listen, O man, from whatever country you may be, whatever your opinions! Here is your history such as I believe to read it, not in books written by your fellow men, who are liars, but in nature, which never lies. Everything that comes from nature will be true. Nothing will be false, except what I might unintentionally have included of my own. The times of which I shall speak are very distant. How much you have changed from what you once were! It is, so to speak, the life of your species I will describe to you according to the qualities that you have received, and that your education and your habits have been able to corrupt but not destroy. There is, I believe, an age at which an individual might want to stop growing older; you will look for the age at which you wish your species to have gone no further. Discontented with your present state for reasons that herald even greater discontent for your unfortunate posterity, you might perhaps wish to be able to go back in time. And this sentiment must lead to the praise of your first ancestors, the criticism of your contemporaries, and dread for those who will have the misfortune of living after you.

- I know that [civilized men] do nothing but boast incessantly of the peace and repose they enjoy in their chains.... But when I see [barbarous man] sacrifice pleasures, repose, wealth, power, and life itself for the preservation of this sole good which is so disdained by those who have lost it; when I see animals born free and despising captivity break their heads against the bars of their prison; when I see multitudes of entirely naked savages scorn European voluptuousness and endure hunger, fire, the sword, and death to preserve only their independence, I feel it does not behoove slaves to reason about freedom.

- In reality, the difference is, that the savage lives within himself while social man lives outside himself and can only live in the opinion of others, so that he seems to receive the feeling of his own existence only from the judgement of others concerning him. It is not to my present purpose to insist on the indifference to good and evil which arises from this disposition, in spite of our many fine works on morality, or to show how, everything being reduced to appearances, there is but art and mummery in even honour, friendship, virtue, and often vice itself, of which we at length learn the secret of boasting; to show, in short, how abject we are, and never daring to ask ourselves in the midst of so much philosophy, benevolence, politeness, and of such sublime codes of morality, we have nothing to show for ourselves but a frivolous and deceitful appearance, honour without virtue, reason without wisdom, and pleasure without happiness.

- Second Treatise on Inequality, translated by Roger D. and Judith R. Masters.

- What therefore is precisely the subject of this discourse? It is to point out, in the progress of things, that moment, when, right taking place of violence, nature became subject to law; to display that chain of surprising events, in consequence of which the strong submitted to serve the weak, and the people to purchase imaginary ease, at the expense of real happiness.

- others have spoken of the natural right of every man to keep what belongs to him, without letting us know what they meant by the word belong.

- The extreme inequalities in the manner of living of the several classes of mankind, the excess of idleness in some, and of labour in others, the facility of irritating and satisfying our sensuality and our appetites, the too exquisite and out of the way aliments of the rich, which fill them with fiery juices, and bring on indigestions, the unwholesome food of the poor, of which even, bad as it is, they very often fall short, and the want of which tempts them, every opportunity that offers, to eat greedily and overload their stomachs; watchings, excesses of every kind, immoderate transports of all the passions, fatigues, waste of spirits, in a word, the numberless pains and anxieties annexed to every condition, and which the mind of man is constantly a prey to; these are the fatal proofs that most of our ills are of our own making, and that we might have avoided them all by adhering to the simple, uniform and solitary way of life prescribed to us by nature.

- The horse, the cat, the bull, nay the ass itself, have generally a higher stature, and always a more robust constitution, more vigour, more strength and courage in their forests than in our houses; they lose half these advantages by becoming domestic animals; it looks as if all our attention to treat them kindly, and to feed them well, served only to bastardize them. It is thus with man himself. In proportion as he becomes sociable and a slave to others, he becomes weak, fearful, mean-spirited, and his soft and effeminate way of living at once completes the enervation of his strength and of his courage.

- some philosophers have even advanced, that there is a greater difference between some men and some others, than between some men and some beasts; it is not therefore so much the understanding that constitutes, among animals, the specifical distinction of man, as his quality of a free agent. Nature speaks to all animals, and beasts obey her voice. Man feels the same impression, but he at the same time perceives that he is free to resist or to acquiesce; and it is in the consciousness of this liberty, that the spirituality of his soul chiefly appears: for natural philosophy explains, in some measure, the mechanism of the senses and the formation of ideas; but in the power of willing, or rather of choosing, and in the consciousness of this power, nothing can be discovered but acts, that are purely spiritual, and cannot be accounted for by the laws of mechanics.

- the knowledge of death, and of its terrors, is one of the first acquisitions made by man, in consequence of his deviating from the animal state.

- who does not perceive that everything seems to remove from savage man the temptation and the means of altering his condition? His imagination paints nothing to him; his heart asks nothing from him. His moderate wants are so easily supplied with what he everywhere finds ready to his hand, and he stands at such a distance from the degree of knowledge requisite to covet more, that he can neither have foresight nor curiosity. The spectacle of nature, by growing quite familiar to him, becomes at last equally indifferent. It is constantly the same order, constantly the same revolutions; he has not sense enough to feel surprise at the sight of the greatest wonders.

- it is impossible to conceive how man, by his own powers alone, without the assistance of communication, and the spur of necessity, could have got over so great an interval. How many ages perhaps revolved, before men beheld any other fire but that of the heavens? How many different accidents must have concurred to make them acquainted with the most common uses of this element? How often have they let it go out, before they knew the art of reproducing it? And how often perhaps has not every one of these secrets perished with the discoverer?

- let us suppose that, without forge or anvil, the instruments of husbandry had dropped from the heavens into the hands of savages, that these men had got the better of that mortal aversion they all have for constant labour; that they had learned to foretell their wants at so great a distance of time; that they had guessed exactly how they were to break the earth, commit their seed to it, and plant trees; that they had found out the art of grinding their corn, and improving by fermentation the juice of their grapes; all operations which we must allow them to have learned from the gods, since we cannot conceive how they should make such discoveries of themselves; after all these fine presents, what man would be mad enough to cultivate a field, that may be robbed by the first comer, man or beast, who takes a fancy to the produce of it. And would any man consent to spend his day in labour and fatigue, when the rewards of his labour and fatigue became more and more precarious in proportion to his want of them? In a word, how could this situation engage men to cultivate the earth, as long as it was not parcelled out among them, that is, as long as a state of nature subsisted.

- The first that offers is how languages could become necessary; for as there was no correspondence between men, nor the least necessity for any, there is no conceiving the necessity of this invention, nor the possibility of it, if it was not indispensable.

- I must further observe that the child having all his wants to explain, and consequently more things to say to his mother, than the mother can have to say to him, it is he that must be at the chief expense of invention, and the language he makes use of must be in a great measure his own work; this makes the number of languages equal to that of the individuals who are to speak them; and this multiplicity of languages is further increased by their roving and vagabond kind of life, which allows no idiom time enough to acquire any consistency; for to say that the mother would have dictated to the child the words he must employ to ask her this thing and that, may well enough explain in what manner languages, already formed, are taught, but it does not show us in what manner they are first formed.

- A new difficulty this, still more stubborn than the preceding; for if men stood in need of speech to learn to think, they must have stood in still greater need of the art of thinking to invent that of speaking.

- speech therefore appears to have been exceedingly requisite to establish the use of speech.

- I earnestly entreat them to consider how much time and knowledge must have been requisite to find out numbers, abstract words, the aorists, and all the other tenses of verbs, the particles, and syntax, the method of connecting propositions and arguments, of forming all the logic of discourse. For my own part, I am so scared at the difficulties that multiply at every step, and so convinced of the almost demonstrated impossibility of languages owing their birth and establishment to means that were merely human, that I must leave to whoever may please to take it up, the task of discussing this difficult problem. "Which was the most necessary, society already formed to invent languages, or languages already invented to form society?"

- I would fain know what kind of misery can be that of a free being, whose heart enjoys perfect peace, and body perfect health? And which is aptest to become insupportable to those who enjoy it, a civil or a natural life? In civil life we can scarcely meet a single person who does not complain of his existence; many even throw away as much of it as they can, and the united force of divine and human laws can hardly put bounds to this disorder.

- Nothing, on the contrary, must have been so unhappy as savage man, dazzled by flashes of knowledge, racked by passions, and reasoning on a state different from that in which he saw himself placed. It was in consequence of a very wise Providence, that the faculties, which he potentially enjoyed, were not to develop themselves but in proportion as there offered occasions to exercise them, lest they should be superfluous or troublesome to him when he did not want them, or tardy and useless when he did. He had in his instinct alone everything requisite to live in a state of nature; in his cultivated reason he has barely what is necessary to live in a state of society.

- In fact, what is generosity, what clemency, what humanity, but pity applied to the weak, to the guilty, or to the human species in general? Even benevolence and friendship, if we judge right, will appear the effects of a constant pity, fixed upon a particular object: for to wish that a person may not suffer, what is it but to wish that he may be happy? Though it were true that commiseration is no more than a sentiment, which puts us in the place of him who suffers, a sentiment obscure but active in the savage, developed but dormant in civilized man, how could this notion affect the truth of what I advance, but to make it more evident.

- In fact, commiseration must be so much the more energetic, the more intimately the animal, that beholds any kind of distress, identifies himself with the animal that labours under it.

- Now it is evident that this identification must have been infinitely more perfect in the state of nature than in the state of reason. It is reason that engenders self-love, and reflection that strengthens it; it is reason that makes man shrink into himself; it is reason that makes him keep aloof from everything that can trouble or afflict him: it is philosophy that destroys his connections with other men.

- their disputes could seldom be attended with bloodshed, were they never occasioned by a more considerable stake than that of subsistence.

- If he happened to make any discovery, he could the less communicate it as he did not even know his children. The art perished with the inventor; there was neither education nor improvement; generations succeeded generations to no purpose; and as all constantly set out from the same point, whole centuries rolled on in the rudeness and barbarity of the first age; the species was grown old, while the individual still remained in a state of childhood.

- Authors are constantly crying out, that the strongest would oppress the weakest; but let them explain what they mean by the word oppression. One man will rule with violence, another will groan under a constant subjection to all his caprices: this is indeed precisely what I observe among us, but I don't see how it can be said of savage men, into whose heads it would be a harder matter to drive even the meaning of the words domination and servitude.

- how is it possible he should ever exact obedience from him, and what chains of dependence can there be among men who possess nothing?

- it is impossible for one man to enslave another, without having first reduced him to a condition in which he can not live without the enslaver's assistance; a condition which, as it does not exist in a state of nature, must leave every man his own master, and render the law of the strongest altogether vain and useless.

- The first man, who, after enclosing a piece of ground, took it into his head to say, "This is mine," and found people simple enough to believe him, was the true founder of civil society. How many crimes, how many wars, how many murders, how many misfortunes and horrors, would that man have saved the human species, who pulling up the stakes or filling up the ditches should have cried to his fellows: Be sure not to listen to this imposter; you are lost, if you forget that the fruits of the earth belong equally to us all, and the earth itself to nobody!

- My pen straightened by the rapidity of time, the abundance of things I have to say, and the almost insensible progress of the first improvements, flies like an arrow over numberless ages, for the slower the succession of events, the quicker I may allow myself to be in relating them.

- Men soon ceasing to fall asleep under the first tree, or take shelter in the first cavern, lit upon some hard and sharp kinds of stone resembling spades or hatchets, and employed them to dig the ground, cut down trees, and with the branches build huts, which they afterwards bethought themselves of plastering over with clay or dirt. This was the epoch of a first revolution, which produced the establishment and distinction of families, and which introduced a species of property, and along with it perhaps a thousand quarrels and battles.

- these conveniences having through use lost almost all their aptness to please, and even degenerated into real wants, the privation of them became far more intolerable than the possession of them had been agreeable; to lose them was a misfortune, to possess them no happiness.

- They now begin to assemble round a great tree: singing and dancing, the genuine offspring of love and leisure, become the amusement or rather the occupation of the men and women, free from care, thus gathered together. Every one begins to survey the rest, and wishes to be surveyed himself; and public esteem acquires a value. He who sings or dances best; the handsomest, the strongest, the most dexterous, the most eloquent, comes to be the most respected: this was the first step towards inequality, and at the same time towards vice. From these first preferences there proceeded on one side vanity and contempt, on the other envy and shame; and the fermentation raised by these new leavens at length produced combinations fatal to happiness and innocence.

- It was thus that every man, punishing the contempt expressed for him by others in proportion to the value he set upon himself, the effects of revenge became terrible, and men learned to be sanguinary and cruel. Such precisely was the degree attained by most of the savage nations with whom we are acquainted. And it is for want of sufficiently distinguishing ideas, and observing at how great a distance these people were from the first state of nature, that so many authors have hastily concluded that man is naturally cruel, and requires a regular system of police to be reclaimed; whereas nothing can be more gentle than he in his primitive state, when placed by nature at an equal distance from the stupidity of brutes, and the pernicious good sense of civilized man.

- this period of the development of the human faculties, holding a just mean between the indolence of the primitive state, and the petulant activity of self-love, must have been the happiest and most durable epoch. The more we reflect on this state, the more convinced we shall be, that it was the least subject of any to revolutions, the best for man, and that nothing could have drawn him out of it but some fatal accident, which, for the public good, should never have happened.

- in a word, as long as they undertook such works only as a single person could finish, and stuck to such arts as did not require the joint endeavours of several hands, they lived free, healthy, honest and happy, as much as their nature would admit, and continued to enjoy with each other all the pleasures of an independent intercourse; but from the moment one man began to stand in need of another's assistance; from the moment it appeared an advantage for one man to possess the quantity of provisions requisite for two, all equality vanished; property started up; labour became necessary; and boundless forests became smiling fields, which it was found necessary to water with human sweat, and in which slavery and misery were soon seen to sprout out and grow with the fruits of the earth.

- it is iron and corn, which have civilized men, and ruined mankind.

- It is a very difficult matter to tell how men came to know anything of iron, and the art of employing it: for we are not to suppose that they should of themselves think of digging it out of the mines, and preparing it for fusion, before they knew what could be the result of such a process. On the other hand, there is the less reason to attribute this discovery to any accidental fire, as mines are formed nowhere but in dry and barren places, and such as are bare of trees and plants, so that it looks as if nature had taken pains to keep from us so mischievous a secret.

- we must suppose them endued with an extraordinary stock of courage and foresight to undertake so painful a work, and have, at so great a distance, an eye to the advantages they might derive from it.

- as men began to extend their views to futurity, and all found themselves in possession of more or less goods capable of being lost, every one in particular had reason to fear, lest reprisals should be made on him for any injury he might do to others.

- The man that had most strength performed most labour; the most dexterous turned his labour to best account; the most ingenious found out methods of lessening his labour; the husbandman required more iron, or the smith more corn, and while both worked equally, one earned a great deal by his labour, while the other could scarce live by his. It is thus that natural inequality insensibly unfolds itself.

- Behold all our natural qualities put in motion; the rank and condition of every man established, not only as to the quantum of property and the power of serving or hurting others, but likewise as to genius, beauty, strength or address, merit or talents; and as these were the only qualities which could command respect, it was found necessary to have or at least to affect them. It was requisite for men to be thought what they really were not. To be and to appear became two very different things, and from this distinction sprang pomp and knavery, and all the vices which form their train.

- In a word, sometimes nothing was to be seen but a contention of endeavours on the one hand, and an opposition of interests on the other, while a secret desire of thriving at the expense of others constantly prevailed. Such were the first effects of property, and the inseparable attendants of infant inequality.

- when estates increased so much in number and in extent as to take in whole countries and touch each other, it became impossible for one man to aggrandise himself but at the expense of some other; and the supernumerary inhabitants, who were too weak or too indolent to make such acquisitions in their turn, impoverished without losing anything, because while everything about them changed they alone remained the same, were obliged to receive or force their subsistence from the hands of the rich.

- And hence began to flow, according to the different characters of each, domination and slavery, or violence and rapine. The rich on their side scarce began to taste the pleasure of commanding, when they preferred it to every other; and making use of their old slaves to acquire new ones, they no longer thought of anything but subduing and enslaving their neighbours.

- the equality once broken was followed by the most shocking disorders.

- There arose between the title of the strongest, and that of the first occupier a perpetual conflict, which always ended in battery and bloodshed. Infant society became a scene of the most horrible warfare: Mankind thus debased and harassed, and no longer able to retreat, or renounce the unhappy acquisitions it had made; labouring, in short merely to its confusion by the abuse of those faculties, which in themselves do it so much honour, brought itself to the very brink of ruin and destruction.

- the rich man, thus pressed by necessity, at last conceived the deepest project that ever entered the human mind: this was to employ in his favour the very forces that attacked him, to make allies of his enemies, to inspire them with other maxims, and make them adopt other institutions as favourable to his pretensions.

- With this view, after laying before his neighbours all the horrors of a situation, which armed them all one against another, which rendered their possessions as burdensome as their wants were intolerable, and in which no one could expect any safety either in poverty or riches, he easily invented specious arguments to bring them over to his purpose. "Let us unite," said he.

- at length men began to butcher each other by thousands without knowing for what; and more murders were committed in a single action, and more horrible disorders at the taking of a single town, than had been committed in the state of nature during ages together upon the whole face of the earth.

- the citizens of a free state suffer themselves to be oppressed merely in proportion as, hurried on by a blind ambition, and looking rather below than above them, they come to love authority more than independence.

- the most refined policy would find it impossible to subdue those men, who only desire to be independent; but inequality easily gains ground among base and ambitious souls, ever ready to run the risks of fortune, and almost indifferent whether they command or obey, as she proves either favourable or adverse to them.

- Were this a proper place to enter into details, I could easily explain in what manner inequalities in point of credit and authority become unavoidable among private persons the moment that, united into one body, they are obliged to compare themselves one with another, and to note the differences which they find in the continual use every man must make of his neighbour.

- I could show how much this universal desire of reputation, of honours, of preference, with which we are all devoured, exercises and compares our talents and our forces: how much it excites and multiplies our passions; and, by creating an universal competition, rivalship, or rather enmity among men, how many disappointments, successes, and catastrophes of every kind it daily causes among the innumerable pretenders whom it engages in the same career. I could show that it is to this itch of being spoken of, to this fury of distinguishing ourselves which seldom or never gives us a moment's respite, that we owe both the best and the worst things among us, our virtues and our vices, our sciences and our errors, our conquerors and our philosophers; that is to say, a great many bad things to a very few good ones.

- Savage man and civilised man differ so much at bottom in point of inclinations and passions, that what constitutes the supreme happiness of the one would reduce the other to despair. The first sighs for nothing but repose and liberty; he desires only to live, and to be exempt from labour; nay, the ataraxy of the most confirmed Stoic falls short of his consummate indifference for every other object. On the contrary, the citizen always in motion, is perpetually sweating and toiling, and racking his brains to find out occupations still more laborious.

- What a spectacle must the painful and envied labours of an European minister of state form in the eyes of a Caribbean! How many cruel deaths would not this indolent savage prefer to such a horrid life, which very often is not even sweetened by the pleasure of doing good?

- the savage lives within himself, whereas the citizen, constantly beside himself, knows only how to live in the opinion of others; insomuch that it is, if I may say so, merely from their judgment that he derives the consciousness of his own existence.

- ever inquiring of others what we are, and never daring to question ourselves on so delicate a point, in the midst of so much philosophy, humanity, and politeness, and so many sublime maxims, we have nothing to show for ourselves but a deceitful and frivolous exterior, honour without virtue, reason without wisdom, and pleasure without happiness. It is sufficient that I have proved that this is not the original condition of man, and that it is merely the spirit of society, and the inequality which society engenders, that thus change and transform all our natural inclinations.

- It appears therefore that man, having teeth and intestines like frugivorous animals, should naturally be placed in that class. And not only do anatomical observations confirm this opinion, but the monuments of antiquity are also very favorable to it. “Dicaearchus,” says St. Jerome, “relates in his books on Greek antiquities that under the reign of Saturn, when the earth was still fertile by itself, no man ate flesh, but that all lived on fruits and vegetables that grew naturally.” … From this one can see that I am neglecting several advantageous considerations that I could turn to account. For since prey is nearly the exclusive subject of fighting among carnivorous animals, and since frugivorous animals live among themselves in continual peace, if the human species were of this latter genus, it is clear that it would have had a much easier time subsisting in the state of nature, and much less need and occasion to leave it.

- Note 5, trans. Donald A. Cress, Hackett Publishing, 1992.

Quotes about Discourse on Inequality

edit- The character of and commitment to equality remains both controversial and disputed among historical and theoretical analysts of classical political economy, and this has been true from the beginning. Smith's earliest writings confronted the critique of commercial society, the vice of luxury, and the inequality both fostered and perpetuated by the regime of private property made by Rousseau in his early economic writing, the Discourse on Inequality (2009 [1755]). Smith responded in at least two ways to this critique of the inherent inequality and unfreedom of commercial society. On the one hand, Smith recognized that a driving force of market operation and expansion was in some sense dependent on that acquisitive psychology that accompanied “the useful inequality in the fortunes of mankind which naturally and necessarily arise from the various degrees of capacity, industry, and diligence in different individuals” (Smith 1983 [1762–3/1766]: 338). This, of course, was to recognize a form of inequality of capacity in society with which Rousseau did not disagree. On the other hand, Smith went further in both the Wealth of Nations and the Lectures on Jurisprudence, and argued untramque partem that the very pursuit of luxury critiqued as vice by Rousseau and others helped to destroy the Gothic ruling class, who “sold their birthrights for baubles,” and in destroying the old feudal order of entrenched inequality, brought both greater liberty and greater equality to those living in the commercial age. In this sense, Smith appeared to employ the rhetorical device of paradiastole to render the putative vice of luxury as a virtue in the classical political economic context, and to suggest that private property – seen as the source of injustice for critics of the commercial order such as Rousseau, was – in the four stages of the progress of society – the very source of justice, because around property basically unsocial natural men had unified in what Kant would later term an “unsocial sociability.” Smith produced other arguments as well for the destruction of monopolies, guilds, and corporations in order to equalize market-driven production and distribution with the understanding (or the hope) that greater social and economic equality would accompany the ever greater expansion of the market. However, it is unquestionable that Smith recognized the inequalities inherent within the actual operation of the market mechanism in his own lifetime, inequalities that later classicals such as Ricardo and Mill would openly admit.

- Shannon C. Stimson, "Classical Political Economy", in Coole, Diana H.; Gibbons, Michael; Ellis, Elisabeth et al., The encyclopedia of political thought (2014)

External links

edit- Encyclopedic article on Discourse on Inequality on Wikipedia

- Works related to Discourse on Inequality on Wikisource

- Media related to Discours sur l'origine et les fondements de l'inégalité parmi les hommes on Wikimedia Commons