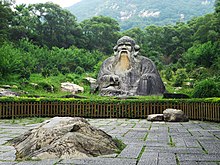

Laozi

6th-century BC semi-legendary Chinese philosopher, founder of Taoism

(Redirected from Laotse)

老子 Lǎozi (c. 6th – 5th century BC) was a Chinese monist philosopher; also called Lao Zi, Lao Tzu, Lao Tse, or Lao Tze. The Tao Te Ching (道德經, Pinyin: Dào Dé Jīng, or Dao De Jing) represents the sole document generally attributed to Laozi.

knowing yourself is true wisdom.

Mastering others is strength; mastering yourself is true power.

Quotes

edit- Those about whom you inquire have moulded with their bones into dust. Nothing but their words remain. When the hour of the great man has struck he rises to leadership; but before his time has come he is hampered in all that he attempts. I have heard that the successful merchant carefully conceals his wealth, and acts as though he had nothing—that the great man, though abounding in achievements, is simple in his manners and appearance. Get rid of your pride and your many ambitions, your affectation and your extravagant aims. Your character gains nothing for all these. This is my advice to you.

- Attributed to Laozi. Laozi speaking to Confucius. Quoted in James Legge, Texts of Taoism, 34; Quoted from Will Durant, Our Oriental Heritage.

used but never used up.

It is like the eternal void:

filled with infinite possibilities.

How do I know this is true?

I look inside myself and see.

and is not intent upon arriving.

A good artist lets his intuition

lead him wherever it wants.

To attain wisdom, remove things every day.

The more he does for others, the happier he is.

The more he gives to others, the wealthier he is.

By not dominating, the Master leads.

- The Tao that can be expressed is not the eternal Tao; The name that can be defined is not the unchanging name.

Non-existence is called the antecedent of heaven and earth; Existence is the mother of all things.

From eternal non-existence, therefore, we serenely observe the mysterious beginning of the Universe; From eternal existence we clearly see the apparent distinctions.

These two are the same in source and become different when manifested.

This sameness is called profundity. Infinite profundity is the gate whence comes the beginning of all parts of the Universe.- Ch. 1, as translated by Ch'u Ta-Kao (1904)

- Also as Tao called Tao is not Tao.

- The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao;

The name that can be named is not the eternal name.

The nameless is the beginning of heaven and earth.

The named is the mother of ten thousand things.

Ever desireless, one can see the mystery.

Ever desiring, one can see the manifestations.

These two spring from the same source but differ in name;

this appears as darkness.

Darkness within darkness.

The gate to all mystery.- Ch. 1, Gia-Fu Feng & Jane English (1972)

- The tao that can be told

is not the eternal Tao

The name that can be named

is not the eternal Name.

The unnameable is the eternally real.

Naming is the origin

of all particular things.

Free from desire, you realize the mystery.

Caught in desire, you see only the manifestations.

Yet mystery and manifestations

arise from the same source.

This source is called darkness.

Darkness within darkness.

The gateway to all understanding.- Ch. 1, as interpreted by Stephen Mitchell (1992)

- The tao that can be described

is not the eternal Tao.

The name that can be spoken

is not the eternal Name.

The nameless is the boundary of Heaven and Earth.

The named is the mother of creation.

Freed from desire, you can see the hidden mystery.

By having desire, you can only see what is visibly real.

Yet mystery and reality

emerge from the same source.

This source is called darkness.

Darkness born from darkness.

The beginning of all understanding.- Ch. 1, as translated by J.H.McDonald (1996) [Public domain translation]

- The way you can go

isn't the real way.

The name you can say

isn't the real name.

Heaven and earth

begin in the unnamed:

name's the mother

of the ten thousand things.

So the unwanting soul

sees what's hidden,

and the ever-wanting soul

sees only what it wants.

Two things, one origin,

but different in name,

whose identity is mystery.

Mystery of all mysteries!

The door to the hidden.- Ch. 1, as interpreted by Ursula K. LeGuin (1998)

- A way can be a guide but not a fixed path

names can be given but not permanent labels

Nonbeing is called the beginning of heaven and earth

being is called the mother of all things

Always passionless thereby observe the subtle

ever intent thereby observe the apparent

These two come from the same source but differ in name

both are considered mysteries

The mystery of mysteries is the gateway of marvels- Ch. 1, as translated by Thomas Cleary (2004)

- The Tao is teachable,

yet understanding my words

is not the same as following the Tao.

The guidance is describable,

yet knowing the description

is not the same as following the guidance.

Non-Being guides to the origin of Heaven and Earth.

Being guides to the mother of all particular things.

Thus, through the guidance of Non-Being,

you can observe the beginning;

through the guidance of Being,

you can observe the returning.

Non-Being and Being come out concurrently,

but point to different directions;

both together can be called the mysterious transforming power.

They constantly transform into each other,

and form the gateways for all wonderful things.- Chapter 1, translated by Yuhui Liang

- A violent wind does not outlast the morning; a squall of rain does not outlast the day. Such is the course of Nature. And if Nature herself cannot sustain her efforts long, how much less can man!

- Chapter 23 as translated by Lionel Giles

- The Tao is like a well:

used but never used up.

It is like the eternal void:

filled with infinite possibilities.It is hidden but always present.

I don't know who gave birth to it.

It is older than God.- Ch. 4, as interpreted by Stephen Mitchell (1992)

- The Tao works like the greatest fountain,

it functions perfectly and never overflows.

All things spray out from it and return into it,

it seems to be the origin of them.

It blunts the sharpness of the powerful,

untangle the knot of the powerless;

softens the glare of the noble,

and stays with the humble.

Oh, it is hidden so deep that it seems not existing.

I do not know its source,

but I know it is the source of the Heavenly God.- Chapter 4, translated by Yuhui Liang

- The Tao is like a bellows:

it is empty yet infinitely capable.

The more you use it, the more it produces;

the more you talk of it, the less you understand.- Ch. 5, as interpreted by Stephen Mitchell (1992)

- The love of Heaven and Earth is impartial,

and they demand nothing from the myriad things.

The love of the sages is impartial,

and they demand nothing from the people.

The cooperation between Heaven and Earth

is much like how a bellows works!

Within the emptiness there is limitless potential;

in moving, it keeps producing without end.

Complaining too much only leads to misfortune.

It is better to stay in the center of serenity.- Chapter 5, translated by Yuhui Liang

- The Tao is called the Great Mother:

empty yet inexhaustible,

it gives birth to infinite worlds.- Ch. 6, as interpreted by Stephen Mitchell (1992)

- The universe is deathless; Is deathless because, having no finite self, it stays infinite. A sound man by not advancing himself stays the further ahead of himself, By not confining himself to himself sustains himself outside himself: By never being an end in himself he endlessly becomes himself.

- Ch. 7

- Thirty spokes unite at the single hub;

It is the empty space which makes the wheel useful.

Mold clay to form a bowl;

It is the empty space which makes the bowl useful.

Cut out windows and doors;

It is the empty space which makes the room useful.- Ch. 11

- Because the eye gazes but can catch no glimpse of it,

It is called elusive.

Because the ear listens but cannot hear it,

It is called the rarefied.

Because the hand feels for it but cannot find it,

It is called the infinitesimal.

These three, because they cannot be further scrutinized,

Blend into one,

Its rising brings no light;

Its sinking, no darkness.

Endless the series of things without name

On the way back to where there is nothing.

They are called shapeless shapes;

Forms without form;

Are called vague semblance.

Go towards them, and you can see no front;

Go after them, and you see no rear.

Yet by seizing on the Way that was

You can ride the things that are now.

For to know what once there was, in the Beginning,

This is called the essence of the Way.- Ch. 14, translated by Arthur Waley, 1934

- A leader is best when people barely know that he exists, not so good when people obey and acclaim him, worst when they despise him. Fail to honor people, They fail to honor you. But of a good leader, who talks little, when his work is done, his aims fulfilled, they will all say, "We did this ourselves."

- Ch. 17

- A longer paraphrase of this quotation, with modern embellishments, is often attributed to Laozi: see "Misattributed" below.

- Since before time and space were,

the Tao is.

It is beyond is and is not.

How do I know this is true?

I look inside myself and see.- Ch. 21, as interpreted by Stephen Mitchell (1992)

- Therefore the Sage embraces the One,

And becomes the model of the world.

He does not reveal himself,

And is therefore luminous.

He does not justify himself,

And is therefore far-famed.

He does not boast himself,

And therefore people give him credit.

He does not pride himself,

And is therefore the ruler among men.

It is because he does not contend

That no one in the world can contend against him.- Ch. 22, as translated by Lin Yutang (1948)

- There is a thing inherent and natural,

Which existed before heaven and earth.

Motionless and fathomless,

It stands alone and never changes;

It pervades everywhere and never becomes exhausted.

It may be regarded as the Mother of the Universe.

I do not know its name. If I am forced to give it a name, I call it Tao, and I name it as supreme.- Ch. 25, as translated by Ch'u Ta-Kao (1904)

- A good traveler has no fixed plans

and is not intent upon arriving.

A good artist lets his intuition

lead him wherever it wants.

A good scientist has freed himself of concepts

and keeps his mind open to what is.Thus the Master is available to all people

and doesn't reject anyone.

He is ready to use all situations

and doesn't waste anything.

This is called embodying the light.- Ch. 27, as interpreted by Stephen Mitchell (1992)

- Variants:

- A good traveller has no fixed plan and is not intent on arriving.

- As quoted in In Search of King Solomon's Mines (2003) by Tahir Shah, p. 217

- A true traveller has no fixed plan, and is not intent on arriving.

- Knowing others is intelligence;

knowing yourself is true wisdom.

Mastering others is strength; mastering yourself is true power.- Ch. 33, as interpreted by Stephen Mitchell (1992)

- Variant translation by Lin Yutang: "He who knows others is learned; he who knows himself is wise".

- Scholars of the highest class, when they hear about the Tao, take it and practice it earnestly.

Scholars of the middle class, when they hear of it, take it half earnestly.

Scholars of the lowest class, when they hear of it, laugh at it.

Without the laughter, there would be no Tao.- Ch. 41

- He who knows that enough is enough will always have enough.

- Ch. 46

- By letting it go it all gets done. The world is won by those who let it go. But when you try and try, the world is beyond the winning.

- Ch. 48, as translated by Raymond B. Blakney (1955)

*To attain knowledge, add things every day.

To attain wisdom, remove things every day.

- Ch. 48

- Block the passages, shut the doors,

And till the end your strength shall not fail.

Open up the passages, increase your doings,

And till your last day no help shall come to you.- Ch. 52 as translated by Arthur Waley (1934)

- The more prohibitions that are imposed on people,

The poorer the people become.

The more laws and regulations that exist,

The more thieves and brigands appear.

The more laws and order are made prominent,

the more thieves and robbers there will be.- Ch. 57

- Variant translation: The more prohibitions there are, the poorer the people will be.

- 千里之行始於足下。

- Qiān lǐ zhī xíng shǐ yú zú xià.

- A journey of a thousand li starts with a single step.

- Ch. 64, line 12

- Variant translations:

- A journey of a thousand [miles] starts with a single step.

- A journey of a thousand miles started with a first step.

- A thousand-mile journey starts from your feet down there.

- As translated by Dr. Hilmar Klaus

- Every journey begins with a single step.

- Governing a large country is like frying a small fish.

- Ch. 60

- When men lack a sense of awe, there will be disaster.

- Chapter 72, translated by Gia Fu Feng

- People starved because the ruler taxed too heavily.

- People are difficult to be ruled,

Because the ruler governs with personal desire and establishes too many laws to confuse the people.- Ch. 75

- Wise men don't need to prove their point;

men who need to prove their point aren't wise.

The Master has no possessions.

The more he does for others, the happier he is.

The more he gives to others, the wealthier he is.

The Tao nourishes by not forcing.

By not dominating, the Master leads.- Ch. 81 as interpreted by Stephen Mitchell (1992)

- Truthful words are not fancy;

fancy words are not truthful.

The good are not argumentative;

the argumentative are not quite good.

The wise know the truth not by storing up knowledge;

those who focus on storing up knowledge do not know the truth.

The sage does not hoard for herself.

The more she helps others,

the richer life she lives.

The more she gives to others,

the more abundance she realizes.

The Tao of heaven benefits all beings without harming anyone.

The Tao of the sage assists the people without competing with anyone.- Chapter 81, translated by Yuhui Liang

Disputed

edit- The mark of a moderate man

is freedom from his own ideas.

Tolerant like the sky,

all-pervading like sunlight,

firm like a mountain,

supple like a tree in the wind,

he has no destination in view

and makes use of anything

life happens to bring his way.- Ch. 59 as interpreted by Stephen Mitchell (1992)

- Nothing that can be said in words is worth saying.

- Various attributions[1]

Misattributed

edit- I am not at all interested in immortality, only in the taste of tea.

- From Lu Tong (also spelled as Lu Tung)

- Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach him how to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.

- This quote's origin is actually unknown (see "give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime" on Wiktionary). This quotation has also been misattributed to Confucius and Guan Zhong.

- Kindness in words creates confidence. Kindness in thinking creates profoundness. Kindness in giving creates love.

- Attributed to Laozi in self-help books and on social media, this quotation is of unknown origin and date.

- What I hear, I forget. What I say, I remember. What I do, I understand.

- This quotation has also been misattributed to Confucius.

- Tell me and I [will] forget. Show me and I [will] remember. Involve me and I [will] understand.

- 不聞不若聞之,聞之不若見之,見之不若知之,知之不若行之;學至於行之而止矣

- From Xun Zi 荀子

- This quotation has also been misattributed to Confucius.

- When the center does not hold, the circle falls apart.

- This is a paraphrase of lines in "The Second Coming" by William Butler Yeats.

- Life is a series of natural and spontaneous changes. Don't resist them – that only creates sorrow. Let reality be reality. Let things flow naturally forward in whatever way they like.

- This quotation's origin is actually unknown, however it is not found in the Dao De Jing.

- 生命是一连串的自发的自然变化。逆流而动只会徒增伤悲。接受现实,万物自然循着规律发展。

- This quotation's origin is actually unknown, however it is not found in the Dao De Jing.

- Care about people's approval and you will be their prisoner.

- Also: "Care about what other people think and you will always be their prisoner"

- Also: "If you care what people think, you will always be their prisoner"

- Appears in Stephen Mitchell's rendering into English of Tao Te Ching chapter 9; but this is an interpretation of Mitchell's which does not appear in the original text or other recognized English translations. Repeated without attribution in Gilliland, Hide Your Goat, a positive thinking book published in 2013.

- When I am anxious it is because I am living in the future. When I am depressed it is because I am living in the past.

- Attributed to "Jimmy R." in Days of Healing, Days of Joy (1987)[2]

- "Go to the people. Live with them. Learn from them. Love them. Start with what they know. Build with what they have. With the best leaders when the work is done, the task accomplished, the people will say, "We have done this ourselves."

- Only the final bold section is connected to Laozi (see Ch. 17 of Tao Te Ching above). The origin of the added first section is unclear.

- An ant on the move does more than a dozing ox

- This is actually a Mexican proverb[3]

- Be careful what you water your dreams with. Water them with worry and fear and you will produce weeds that choke the life from your dream. Water them with optimism and solutions and you will cultivate success. Always be on the lookout for ways to turn a problem into an opportunity for success. Always be on the lookout for ways to nurture your dream.

Quotes about Laozi

edit- We believe that the Daoist tradition started as a response to the excesses of civilization. That was Lao Tzu's deal anyway. Lots of similar traditions dealt with issues of work and status and anxiety and nature the same way. But they were all, pretty much, taken over by fascists and real reactionaries. Even Taoism was taken over by charlatans and phonies. But the pure undogmatic centre of lots of traditions (Christianity, Vedism, Buddhism etc) is all the same. And that's Daoism.

- According to religious scholar Huston Smith, Taoism has only one basic text, the Tao Te Ching (or, in English, The Way and Its Power), a slim volume that, as Smith says, can be read in half an hour or a lifetime. Legend has it that a Chinaman by the name of Lao Tzu one day said "Enough!" (loosely translated from the Chinese), hopped on a water buffalo (possibly with rust coloration), and started heading a-way out west to Tibet.

On his way out, someone stopped Lao Tzu and asked if he would write down the tenets of his ethos before leaving town. Being a lazy man, Lao Tzu lodged his water buffalo against an abutment long enough to write the Tao Te Ching's 81 short verses. When finished, he kicked his water buffalo into gear and, tossing his ringer to the man, rode off into the misty horizon of legend and myth.

Regardless of whether the legend is true, or whether Lao Tzu even really existed, the Chinaman is not the issue here, Dudes. The issue is that the Tao Te Ching is the perfect expression of Taoism's wu wei of life, or in the parlance of Huston Smith, a life of creative quietude in which "the conscious mind must relax, stop standing in its own light, let go" so that it can flow with the Tao (or Way) of the universe.- Rev. Dwayne Eutsey, in the Introduction of the Dudeist holy book The Dude De Ching (2010)

- Lao-tse may be regarded as the deepest thinker of Chinese antiquity.

- William Howitt, in The History of the Supernatural (1863), p. 321

- Helpmeat too, contrasta toga, his fiery goosemother, laotsey taotsey, woman who did, he tell princes of the age about. You sound on me, judges! Suppose we brisken up. Kings! Meet the Mem, Avenlith, all viviparous out of couple of lizards. She just as fenny as he is fulgar. How laat soever her latest still her sawlogs come up all standing. Psing a psalm of psexpeans, apocryphul of rhyme! His cheekmole of allaph foriverever her allinall and his Quran never teach it her the be the owner of thyself.

- James Joyce, in Finnegans Wake (1939)

- My father's favorite book was a copy of Lao Tzu, and seeing it in his hands a lot, I as a kid got interested. Of course, it's very accessible to a kid, it's short, it's kind of like poetry, it seems rather simple. And so I got into that pretty young, and obviously found something that I wanted, and it got very deep into me.

- 1982 interview in Conversations with Ursula Le Guin

- I think Lao Tse would course you have to act in order to be alive. You do things, and all craft, all skill, all art is action, but I think what the difference is with weaving, the very good weaver-the weavers who know their craft so thoroughly that it is part of them-does it without any fuss, without hard work. It is easy. It is not so much in that case action against non-action-that's more with political choices and things like that. It's whether the work is hard or the work is easy. Lao Tse says, "If you're on the way, if you're following Tao, all work is easy." It becomes part of you, you do it naturally, and then you do it right. Whatever it is it comes right, of course, that's Zen, the whole idea. You make one brush stroke and if it isn't right, it just isn't right, but if it's right, it's perfectly right. It's all mystical, the underlying mysticism, and it's all outlook, but it's also true, you know, when you know your craft perfectly well, when you really know what you're doing, then it's easy, and it's a pleasure.

- 2002 interview in Conversations with Ursula Le Guin

- If there is one book in the whole of Oriental literature which one should read above all the others, it is, in my opinion, Laotse's Book of Tao. If there is one book that can claim to interpret for us the spirit of the Orient, or that is necessary to the understanding of characteristic Chinese behaviour, including literally "the ways that are dark," it is the Book of Tao. For Laotse's book contains the first enunciated philosophy of camouflage in the world; it teaches the wisdom of appearing foolish, the success of appearing to fail, the strength of weakness and the advantage of lying low, the benefit of yielding to your adversary and the futility of contention for power. It accounts in fact for any mellowness that may be seen in Chinese social and individual behaviour. If one reads enough of this Book, one automatically acquires the habit and ways of the Chinese. I would go further and say that if I were asked what antidote could be found in Oriental literature and philosophy to cure this contentious modern world of its inveterate belief in force and struggle for power, I would name this book of "5,000 words" written some 2,400 years ago. For Laotse (born about 570 B.C.) has the knack of making Hitler and other dreamers of world mastery appear foolish and ridiculous. The chaos of the modem world, I believe, is due to the total lack of a philosophy of the rhythm of life such as we find in Laotse and his brilliant disciple Chuangtse, or anything remotely resembling it. And furthermore, if there is one book advising against the multifarious activities and futile busyness of the modern man, I would again say it is Laotse's Book of Tao. It is one of the profoundest books in the world's philosophy.

- Lin Yutang, The Wisdom of China and India (New York: Random House, 1942), "Laotse, the Book of Tao (The Tao Teh Ching)", Introduction, p. 579

- Laotse packs his oracular wisdom into five thousand words of concentrated brilliance. No thinker ever wrote fewer words to embody a whole philosophy and had as much influence upon the thought of a nation.

- Lin Yutang, From Pagan to Christian (Cleveland and New York: World Publishing, 1959), Ch. 4: "The Peak of Mount Tao", pp. 107–108

- Political leaders are never leaders. For leaders we have to look to the Awakeners! Lao Tse, Buddha, Socrates, Jesus, Milarepa, Gurdjiev, Krishnamurti.

- Henry Miller, in My Bike & Other Friends (1977), p. 12

- The oldest known Chinese sage is Lao-Tze, the founder of Taoism. "Lao Tze" is not really a proper name, but means merely "the old philosopher." He was (according to tradition) an older contemporary of Confucius, and his philosophy is to my mind far more interesting. He held that every person, every animal, and every thing has a certain way or manner of behaving which is natural to him, or her, or it, and that we ought to conform to this way ourselves and encourage others to conform to it. "Tao" means "way," but used in a more or less mystical sense, as in the text: "I am the Way and the Truth and the Life." I think he fancied that death was due to departing from the "way," and that if we all lived strictly according to nature we should be immortal, like the heavenly bodies.

- Bertrand Russell, in The Problem of China (1922), Ch. XI - Chinese and Western Civilization Contrasted

- The greatest achievement of humanity is not its works of art, science, or technology, but the recognition of its own dysfunction, its own madness. In the distant past, this recognition already came to a few individuals. A man called Gautama Siddhartha, who lived 2,600 years ago in India, was perhaps the first who saw it with absolute clarity. Later the title Buddha was conferred upon him. Buddha means “the awakened one.” At about the same time, another of humanity's early awakened teachers emerged in China. His name was Lao Tzu. He left a record of his teaching in the form of one of the most profound spiritual books ever written, the Tao Te Ching. To recognize one's own insanity, is of course, the arising of sanity, the beginning of healing and transcendence.

- Lao Tzu was able to teach the Tao because he not only could let the Tao guide him and have direct experience of the Tao, but also was able to introduce and utilize the powerful coupling concepts of Non-Being and Being to describe and teach the Tao, so that he knew what he taught and knew how to teach for sure. And this is the main reason for Lao Tzu to be the greatest teacher of the Tao in the history.

- Yuhui Liang, in Tao Te Ching: The English Version That Makes Good Sense (2018), p. 121

See also

edit

References

edit- ↑ McGuirk, Kevin. “‘[T]He Apple an Apple’: Ammons, Bloom, and ‘the Ten Thousand Things’—with Emerson and Lao Tzu.” Journal of Modern Literature 44, no. 1 (2020): 77–95. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/jmodelite.44.1.05.

- ↑ Jean Howarth; Mike Walton (1995). Moments of Reflection. Heinemann Educational Publishers.

- ↑ Fayek S. Hourani, Daily Bread for Your Mind and Soul: A Handbook of Transcultural Proverbs and Sayings.

- ↑ Gudmundur O. Sigurdarson. The first step: a peek at the real world.

External links

edit- 15 Tao Te Ching English translations @GeekFarm.org

- An in-deep introduction to Lao Tzu's Tao Te Ching, providing answers to the difficult and important questions about the Tao Te Ching by Yuhui Liang.

- Illustrated Translations in English by multiple authors: "TaoTeChingMe.com - translations and interpretations

- Tao Te King as translated by Ch'u Ta-Kao (1904)

- Interpretation by Stephen Mitchell: On-line Tao Te Ching.

- Translation by j.h. mcdonald: Religions and Scriptures: Tao Te Ching.

- An online translation by Charles Muller: Professor Muller's site: Daode jing.

- Translation by Chad Hansen: On-line Tao Te Ching: both English and modern Chinese. Also Zhuangzi.

- An Informal online interpolation by Ron Hogan is available in several formats at Beatrice.com: Tao Te Ching. An iPod formatted version of this translation is available at SwiftlyTilting.com: The Tao Te Ching for your iPod

- Translation by Sonja Elen Kisa: On-line Tao Te Ching (selected poems) going by the name The Flow and the Power of Good

- Translation from the City University of Hong Kong: On-line Tao Te Ching. Classical and Vernacular Chinese, and English.

- 老子 Lǎozĭ 道德經 Dàodéjīng - 拼音 Pīnyīn+王弼 WángBì+馬王堆 Mǎwángduī+郭店 Guōdiàn+大一生水 Tàiyī Shēngshǔi

- Interpolation by Peter Merel: On-line Tao Te Ching.

- Commentary by Swami Nirmalananda Giri: Commentary on the Tao Te Ching.

- Wayne L. Wang The Dynamic Tao and Its Manifestations: Tao and modern scientific thoughts

- Tao De Ching (GNL's Not Lao) [1]

- Sanderson Beck's Interpretation

- Translations and commentary by Nina Correa

- A "plain English" online interpolation of Chapters 1–37 ("Tao") by the Universal Dialectic Institute: Tao: The Way of Nature

- Free mp3 downloads of Tao Te Ching narrated by Michael Scott of ThoughtAudio.com.

- Multiple English translations of Lao Tzu's the Tao Te Ching - Compare translations side-by-side

Chinese versions

edit- Comparison Chart Chinese characters with PinYin spellings of the Wang Bi, HeShang Gong, Mawangdui A and B, Guodian texts.

- Bamboo slips of the Guodian text Photographs of the Guodian Bamboo Slips with modern equivalents of the Chinese characters, PinYin and Wade Giles spellings, and English definitions.