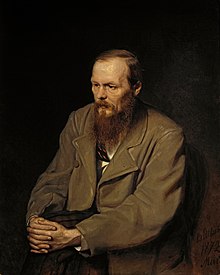

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Russian novelist (1821–1881)

(Redirected from Fyodor Dostoevsky)

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky or Dostoevsky [Фёдор Миха́йлович Достое́вский] (11 November 1821 - 9 February 1881) was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist, and journalist. Dostoevsky's literary works explore the human condition in the troubled political, social, and spiritual atmospheres of 19th-century Russia, and engage with a variety of philosophical and religious themes. Many literary critics rate him as one of the greatest novelists in all of world literature, as multiple of his works are considered highly influential masterpieces.

General

edit- To study the meaning of man and of life — I am making significant progress here. I have faith in myself. Man is a mystery: if you spend your entire life trying to puzzle it out, then do not say that you have wasted your time. I occupy myself with this mystery, because I want to be a man.

- Personal correspondence (1839), as quoted in Dostoevsky: His Life and Work (1971) by Konstantin Mochulski, as translated by Michael A. Minihan, p. 17

- I want to say to you, about myself, that I am a child of this age, a child of unfaith and scepticism, and probably (indeed I know it) shall remain so to the end of my life. How dreadfully has it tormented me (and torments me even now) this longing for faith, which is all the stronger for the proofs I have against it. And yet God gives me sometimes moments of perfect peace; in such moments I love and believe that I am loved; in such moments I have formulated my creed, wherein all is clear and holy to me. This creed is extremely simple; here it is: I believe that there is nothing lovelier, deeper, more sympathetic, more rational, more manly, and more perfect than the Saviour; I say to myself with jealous love that not only is there no one else like Him, but that there could be no one. I would even say more: If anyone could prove to me that Christ is outside the truth, and if the truth really did exclude Christ, I should prefer to stay with Christ and not with truth.

- Letter To Mme. N. D. Fonvisin (1854), as published in Letters of Fyodor Michailovitch Dostoevsky to his Family and Friends (1914), translated by Ethel Golburn Mayne, Letter XXI, p. 71

- Neither a person nor a nation can exist without some higher idea. And there is only one higher idea on earth, and it is the idea of the immortality of the human soul, for all other "higher" ideas of life by which humans might live derive from that idea alone.

- I think that the principal and most basic spiritual need of the Russian People is the need for suffering, incessant and unslakeable suffering, everywhere and in everything. I think the Russian People have been infused with this need to suffer from time immemorial. A current of martyrdom runs through their entire history, and it flows not only from external misfortunes and disasters but springs from the very heart of the People themselves. There is always an element of suffering even in the happiness of the Russian People, and without it their happiness is incomplete.

- A Writer's Diary, Volume 1: 1873-1876 (1994), p. 161-162

- Money is coined liberty, and so it is ten times dearer to the man who is deprived of freedom. If money is jingling in his pocket, he is half consoled, even though he cannot spend it. But money can always and everywhere be spent, and, moreover, forbidden fruit is sweetest of all.

- The House of the Dead (1915), as translated by Constance Garnett, p. 16

- It is not as a child that I believe and confess Jesus Christ. My hosanna is born of a furnace of doubt.

- As quoted in Kierkegaard, the Melancholy Dane (1950) by Harold Victor Martin.

- Variant translation:

- I believe in Christ and confess him not like some child; my hosanna has passed through an enormous furnace of doubt.

- Last Notebook (1880–1881), Literaturnoe nasledstvo, 83: 696; as quoted in Kenneth Lantz, The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia (2004), p. 21, hdn ISBN 0-313-30384-3

- A great many people were put down as mad among us last year. And in such language! "With such original talent" ... "and yet, after all, it appears" ... "however, one ought to have foreseen it long ago." That is rather artful; so that from the point of view of pure art one may really commend it. Well, but after all, these so-called madmen have turned out cleverer than ever. So it seems the critics can call them mad, but they cannot produce any one better.

The wisest of all, in my opinion, is he who can, if only once a month, call himself a fool — a faculty unheard of nowadays. In old days, once a year at any rate a fool would recognise that he was a fool, but nowadays not a bit of it. And they have so muddled things up that there is no telling a fool from a wise man. They have done that on purpose.

I remember a witty Spaniard saying when, two hundred and fifty years ago, the French built their first madhouses: "They have shut up all their fools in a house apart, to make sure that they are wise men themselves." Just so: you don't show your own wisdom by shutting some one else in a madhouse. "K. has gone out of his mind, means that we are sane now." No, it doesn't mean that yet.- "Bobok : From Somebody's Diary" as translated by Constance Garnett in Short Stories (1900)

- The second half of a man's life is made up of nothing but the habits he has acquired during the first half.

- As quoted in Peter's Quotations : Ideas for Our Time (1979) by Laurence J. Peter, p. 299

- Russia was a slave in Europe but would be a master in Asia.

- As quoted in "Dilemmas of Empire 1850-1918: Power, Territory, Identity" by Dominic Livien in Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 34, No.2 (April 1999), pp. 180

- All writers, not ours alone but foreigners also, who have sought to represent Absolute Beauty, were unequal to the task, for it is an infinitely difficult one. The beautiful is the ideal ; but ideals, with us as in civilized Europe, have long been wavering. There is in the world only one figure of absolute beauty: Christ. That infinitely lovely figure is, as a matter of course, an infinite marvel.

- Fyodor Dostoevsky in a letter to his Niece Sofia Alexandrovna, Geneva, January 1, 1868. Ethel Golburn Mayne (1879), Letters of Fyodor Michailovitch Dostoyevsky to His Family and Friends, Dostoevsky's Letters XXXIX, p. 136.

- The modern negationist declares himself declares himself openly in favour of the devil's advice and maintains that it is more likely to result in man's happiness than the teachings of Christ. To our foolish but terrible Russian socialism (for our youth is mixed up in it) it is a directive and, it seems, a very powerful one: the loaves of bread, the Tower of Babel (that is, the future reign of socialism) and the complete enslavement of the freedom of conscience - that is what the desperate negationist is striving to achieve. The difference is, that our socialists (and they are not only the hole-and-corner nihilists) are conscious Jesuits and liars who do not admit that their ideal is the ideal of the coercion of the human conscience and the reduction of mankind to the level of cattle. While my socialist (Ivan Karamazov) is a sincere man who frankly admits that he agrees with the views of the Grand Inquisitor and that Christianity seems to have raised man much higher than his actual position entitles him. The question I should like to put to them is, in a nutshell, this: "Do you despise or do you respect mankind, you - its future saviours?"

- Dostoyevsky, in a letter to Katkov, the reactionary editor of The Moscow Herald, in which The Brothers Karamazov was serialized

- As quoted by David Magarshack in his 1958 translation of The Brothers Karamazov

The Insulted and the Injured (1861)

edit- If you want to be respected by others the great thing is to respect yourself. Only by that, only by self-respect will you compel others to respect you.

Notes from Underground (1864)

edit- Я человек больной... Я злой человек. Непривлекательный я человек.

- I am a sick man... I am a wicked man. An unattractive man.

- Part 1, Chapter 1 (page 7)

- It was not only that I could not become spiteful, I did not know how to become anything; neither spiteful nor kind, neither a rascal nor an honest man, neither a hero nor an insect. Now, I am living out my life in my corner, taunting myself with the spiteful and useless consolation that an intelligent man cannot become anything seriously, and it is only the fool who becomes anything.

- Part 1, Chapter 1 (page 8)

- ...что слишком сознавать — это болезнь, настоящая, полная болезнь.

- To be acutely conscious is a disease, a real, honest-to-goodness disease.

- Part 1, Chapter 2 (page 9)

- Often paraphrased: To think too much is a disease.

- Once it's been proved to you that you're descended from an ape, it's no use pulling a face; just accept it. Once they've proved to you that a single droplet of your own fat must be dearer to you than a hundred thousand of your fellow human beings and consequently that all so-called virtues and duties are nothing but ravings and prejudices, then accept that too, because there's nothing to be done.

- Part 1 Chapter 3 (page 14)

- Granted I am a babbler, a harmless vexatious babbler, like all of us. But what is to be done if the direct and sole vocation of every intelligent man is babble, that is, the intentional pouring of water through a sieve?

- Part 1, Chapter 5 (page 19)

- When... in the course of all these thousands of years has man ever acted in accordance with his own interests?

- Part 1, Chapter 7 (page 20)

- And what is it in us that is mellowed by civilization? All it does, I'd say, is to develop in man a capacity to feel a greater variety of sensations. And nothing, absolutely nothing else. And through this development, man will yet learn how to enjoy bloodshed. Why, it has already happened . . . . Civilization has made man, if not always more bloodthirsty, at least more viciously, more horribly bloodthirsty.

- Part 1, Chapter 7 (page 23)

- The best definition of man is: a being that goes on two legs and is ungrateful.

- Variant translation: If I had to define man it would be: a biped, ungrateful.

- Part 1, Chapter 8 (page 28)

- The formula 'two plus two equals five' is not without its attractions.

- Part 1, Chapter 9 (page 31)

- To care only for well-being seems to me positively ill-bred. Whether it's good or bad, it is sometimes very pleasant, too, to smash things.

- Part 1, Chapter 9 (page 32)

- Every man has some reminiscences which he would not tell to everyone, but only to his friends. He has others which he would not reveal even to his friends, but only to himself, and that in secret. But finally there are still others which a man is even afraid to tell himself, and every decent man has a considerable number of such things stored away. That is, one can even say that the more decent he is, the greater the number of such things in his mind.

- Part 1, Chapter 11 (page 35)

- The characteristics of our "romantics" are absolutely and directly opposed to the transcendental European type, and no European standard can be applied to them. (Allow me to make use of this word "romantic" — an old-fashioned and much respected word which has done good service and is familiar to all.) The characteristics of our romantics are to understand everything, to see everything and to see it often incomparably more clearly than our most realistic minds see it; to refuse to accept anyone or anything, but at the same time not to despise anything; to give way, to yield, from policy; never to lose sight of a useful practical object (such as rent-free quarters at the government expense, pensions, decorations), to keep their eye on that object through all the enthusiasms and volumes of lyrical poems, and at the same time to preserve "the sublime and the beautiful" inviolate within them to the hour of their death, and to preserve themselves also, incidentally, like some precious jewel wrapped in cotton wool if only for the benefit of "the sublime and the beautiful." Our "romantic" is a man of great breadth and the greatest rogue of all our rogues, I assure you .... I can assure you from experience, indeed. Of course, that is, if he is intelligent. But what am I saying! The romantic is always intelligent, and I only meant to observe that although we have had foolish romantics they don't count, and they were only so because in the flower of their youth they degenerated into Germans, and to preserve their precious jewel more comfortably, settled somewhere out there — by preference in Weimar or the Black Forest.

- Part 2, Chapter 1 (pages 45-46)

- I could never stand more than three months of dreaming at a time without feeling an irresistible desire to plunge into society. To plunge into society meant to visit my superior, Anton Antonich Syetochkin. He was the the only permanent acquaintance I have had in my life, and I even wonder at the fact myself now. But I even went to see him only when that phase came over me, and when my dreams had reached such a point of bliss that it became essential to embrace my fellows and all mankind immediately. And for that purpose I needed at least one human being at hand who actually existed. I had to call on Anton Antonich, however, on Tuesday — his at-home day; so I always had to adjust my passionate desire to embrace humanity so that it might fall on a Tuesday.

- Part 2, Chapter 2 (page 56)

- ... people only count their misfortunes; their good luck they take no account of. But if they were to take everything into account, as they should, they'd find that they had their fair share of it.

- Part 2, Chapter 6 (page 86)

- Yes — you, you alone must pay for everything because you turned up like this, because I'm a scoundrel, because I'm the nastiest, most ridiculous, pettiest, stupidest, and most envious worm of all those living on earth who're no better than me in any way, but who, the devil knows why, never get embarrassed, while all my life I have to endure insults from every louse — that's my fate. What do I care that you do not understand any of this?

- Part 2, Chapter 9 (pages 108-109)

The Gambler (1866)

edit- And now once again I asked myself the question: do I love her? And once more I could not answer, that is to say, again, for the hundreth time, I answered that I hated her.

- Is it really not possible to touch the gaming table without being instantly infected by superstition?

- A gentleman, even if he loses everything he owns, must show no emotion. Money must be so far beneath a gentleman that it is hardly worth troubling about.

Crime and Punishment (1866)

edit- These are just a few samples; for more quotes from this work, see Crime and Punishment

- All is in a man's hands and he lets it all slip from cowardice, that's an axiom. It would be interesting to know what it is men are most afraid of. Taking a new step, uttering a new word is what they fear most.

- Man grows used to everything, the scoundrel.

- Talking nonsense is man's only privilege that distinguishes him from all other organisms.

- "You're a gentleman," they used to say to him. "You shouldn't have gone murdering people with a hatchet; that's no occupation for a gentleman."

- Do a man dirt, yourself you hurt.

- Nothing in the world is harder than speaking the truth and nothing easier than flattery. If there’s the hundredth part of a false note in speaking the truth, it leads to a discord, and that leads to trouble. But if all, to the last note, is false in flattery, it is just as agreeable, and is heard not without satisfaction. It may be a coarse satisfaction, but still a satisfaction. And however coarse the flattery, at least half will be sure to seem true. That’s so for all stages of development and classes of society.

- Variant translation: Nothing in this world is harder than speaking the truth, nothing easier than flattery.

- Accept suffering and achieve atonement through it — that is what you must do.

- If not reason, then the devil.

- Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart. The really great men must, I think, have great sadness on Earth.

- The more cunning a man is, the less he suspects that he will be caught in a simple thing. The more cunning a man is, the simpler the trap he must be caught in.

- Your worst sin is that you have destroyed and betrayed yourself for nothing.

- A widow, the mother of a family, and from her heart she produces chords to which my whole being responds.

- It wasn't the New World that mattered ... Columbus died almost without seeing it; and not really knowing what he had discovered. It's life that matters, nothing but life — the process of discovering, the everlasting and perpetual process, not the discovery itself, at all. But what's the use of talking! I suspect that all I'm saying now is so like the usual commonplaces that I shall certainly be taken for a lower-form schoolboy sending in his essay on "sunrise", or they'll say perhaps that I had something to say, but that I did not know how to "explain" it. But I'll add, that there is something at the bottom of every new human thought, every thought of genius, or even every earnest thought that springs up in any brain, which can never be communicated to others, even if one were to write volumes about it and were explaining one's idea for thirty-five years; there's something left which cannot be induced to emerge from your brain, and remains with you forever; and with it you will die, without communicating to anyone perhaps the most important of your ideas. But if I too have failed to convey all that has been tormenting me for the last six months, it will, anyway, be understood that I have paid very dearly for attaining my present "last conviction." This is what I felt necessary, for certain objects of my own, to put forward in my "Explanation". However, I will continue.

- Lack of originality, everywhere, all over the world, from time immemorial, has always been considered the foremost quality and the recommendation of the active, efficient and practical man...

- To kill someone for committing murder is a punishment incomparably worse than the crime itself. Murder by legal sentence is immeasurably more terrible than murder by brigands.

- A fool with a heart and no sense is just as unhappy as a fool with sense and no heart.

- It is better to be unhappy and know the worst, than to be happy in a fool's paradise.

- It was evident that he revived by fits and starts. He would suddenly come to himself from actual delirium for a few minutes; he would remember and talk with complete consciousness, chiefly in disconnected phrases which he had perhaps thought out and learnt by heart in the long weary hours of his illness, in his bed, in sleepless solitude.

- Inventors and geniuses have almost always been looked on as no better than fools at the beginning of their career, and very frequently at the end of it also.

- I consider you the most honest and truthful of men, more honest and truthful than anyone; and if they say that your mind . . . that is, that you're sometimes afflicted in your mind, it's unjust. I made up my mind about that, and disputed with others, because, though you really are mentally afflicted (you won't be angry with that, of course; I'm speaking from a higher point of view), yet the mind that matters is better in you than in any of them. It's something, in fact, they have never dreamed of. For there are two sorts of mind: one that matters, and one that doesn't matter.

- I have never in my life met a man like him for noble simplicity, and boundless truthfulness. I understood from the way he talked that anyone who chose could deceive him, and that he would forgive anyone afterwards who had deceived him, and that was why I grew to love him.

- Humiliate the reason and distort the soul...

- Nor is there any embarrassment in the fact that we're ridiculous, isn't it true? For it's actually so, we are ridiculous, light-minded, with bad habits, we're bored, we don't know how to look, how to understand, we're all like that, all, you, and I, and they! Now, you're not offended when I tell you to your face that you're ridiculous? And if so, aren't you material? You know, in my opinion it's sometimes even good to be ridiculous, if not better: we can the sooner forgive each other, the sooner humble ourselves; we can't understand everything at once, we can't start right out with perfection! To achieve perfection, one must first begin by not understanding many things! And if we understand too quickly, we may not understand well. This I tell you, you, who have already been able to understand. .. and not understand ... so much. I'm not afraid for you now;

- Who consciously throws himself into the water or onto the knife?

- ...князь утверждает, что мир спасет красота! А я утверждаю, что у него оттого такие игривые мысли, что он теперь влюблен.

- The prince says that the world will be saved by beauty! And I maintain that the reason he has such playful ideas is that he is in love.

- Pass by us, and forgive us our happiness.

- It's easier for a Russian to become an atheist than for anyone else in the world.

- First of all, this prince is an idiot, and, secondly, he is a fool--knows nothing of the world, and has no place in it.

- The Idiot, Part IV., Chapter V.

The Possessed (1872)

edit- Also known as The Demons and The Devils · Full text online at Project Gutenberg

- Man is unhappy because he doesn't know he's happy. It's only that.

- Part II, Ch. I

- Hold your tongue; you won't understand anything. If there is no God, then I am God.

- Kirilov, Part III, Ch. VI, "A busy night"

- Using primarily the translation of Constance Garnett (1900) - Full text at Wikisource

- I am a ridiculous person. Now they call me a madman. That would be a promotion if it were not that I remain as ridiculous in their eyes as before. But now I do not resent it, they are all dear to me now, even when they laugh at me — and, indeed, it is just then that they are particularly dear to me. I could join in their laughter — not exactly at myself, but through affection for them, if I did not feel so sad as I look at them. Sad because they do not know the truth and I do know it. Oh, how hard it is to be the only one who knows the truth! But they won't understand that. No, they won't understand it.

- I

- Variant translation: I am a ridiculous man. They call me a madman now. That would be a distinct rise in my social position were it not that they still regard me as being as ridiculous as ever. But that does not make me angry any more. They are all dear to me now even while they laugh at me — yes, even then they are for some reason particularly dear to me. I shouldn't have minded laughing with them — not at myself, of course, but because I love them — had I not felt so sad as I looked at them. I feel sad because they do not know the truth, whereas I know it. Oh, how hard it is to be the only man to know the truth! But they won't understand that. No, they will not understand.

- As translated by David Magarshack

- I gave up caring about anything, and all the problems disappeared.

And it was after that that I found out the truth. I learnt the truth last November — on the third of November, to be precise — and I remember every instant since.- I

- The sky was horribly dark, but one could distinctly see tattered clouds, and between them fathomless black patches. Suddenly I noticed in one of these patches a star, and began watching it intently. That was because that star had given me an idea: I decided to kill myself that night.

- I

- It seemed clear to me that life and the world somehow depended upon me now. I may almost say that the world now seemed created for me alone: if I shot myself the world would cease to be at least for me. I say nothing of its being likely that nothing will exist for anyone when I am gone, and that as soon as my consciousness is extinguished the whole world will vanish too and become void like a phantom, as a mere appurtenance of my consciousness, for possibly all this world and all these people are only me myself.

- II

- Dreams, as we all know, are very queer things: some parts are presented with appalling vividness, with details worked up with the elaborate finish of jewellery, while others one gallops through, as it were, without noticing them at all, as, for instance, through space and time. Dreams seem to be spurred on not by reason but by desire, not by the head but by the heart, and yet what complicated tricks my reason has played sometimes in dreams, what utterly incomprehensible things happen to it!

- II

- Yes, I dreamed a dream, my dream of the third of November. They tease me now, telling me it was only a dream. But does it matter whether it was a dream or reality, if the dream made known to me the truth? If once one has recognized the truth and seen it, you know that it is the truth and that there is no other and there cannot be, whether you are asleep or awake. Let it be a dream, so be it, but that real life of which you make so much I had meant to extinguish by suicide, and my dream, my dream — oh, it revealed to me a different life, renewed, grand and full of power!

- II

- I suddenly dreamt that I picked up the revolver and aimed it straight at my heart — my heart, and not my head; and I had determined beforehand to fire at my head, at my right temple. After aiming at my chest I waited a second or two, and suddenly my candle, my table, and the wall in front of me began moving and heaving. I made haste to pull the trigger.

- III

- In dreams you sometimes fall from a height, or are stabbed, or beaten, but you never feel pain unless, perhaps, you really bruise yourself against the bedstead, then you feel pain and almost always wake up from it. It was the same in my dream. I did not feel any pain, but it seemed as though with my shot everything within me was shaken and everything was suddenly dimmed, and it grew horribly black around me. I seemed to be blinded, and it benumbed, and I was lying on something hard, stretched on my back; I saw nothing, and could not make the slightest movement.

- III

- On our earth we can only love with suffering and through suffering. We cannot love otherwise, and we know of no other sort of love. I want suffering in order to love. I long, I thirst, this very instant, to kiss with tears the earth that I have left, and I don't want, I won't accept life on any other!"

- III

- The children of the sun, the children of their sun — oh, how beautiful they were! Never had I seen on our own earth such beauty in mankind. Only perhaps in our children, in their earliest years, one might find, some remote faint reflection of this beauty. The eyes of these happy people shone with a clear brightness. Their faces were radiant with the light of reason and fullness of a serenity that comes of perfect understanding, but those faces were gay; in their words and voices there was a note of childlike joy. Oh, from the first moment, from the first glance at them, I understood it all! It was the earth untarnished by the Fall; on it lived people who had not sinned. They lived just in such a paradise as that in which, according to all the legends of mankind, our first parents lived before they sinned; the only difference was that all this earth was the same paradise. These people, laughing joyfully, thronged round me and caressed me; they took me home with them, and each of them tried to reassure me. Oh, they asked me no questions, but they seemed, I fancied, to know everything without asking, and they wanted to make haste to smoothe away the signs of suffering from my face.

- III

- Well, granted that it was only a dream, yet the sensation of the love of those innocent and beautiful people has remained with me for ever, and I feel as though their love is still flowing out to me from over there. I have seen them myself, have known them and been convinced; I loved them, I suffered for them afterwards. Oh, I understood at once even at the time that in many things I could not understand them at all ... But I soon realised that their knowledge was gained and fostered by intuitions different from those of us on earth, and that their aspirations, too, were quite different. They desired nothing and were at peace; they did not aspire to knowledge of life as we aspire to understand it, because their lives were full. But their knowledge was higher and deeper than ours; for our science seeks to explain what life is, aspires to understand it in order to teach others how to love, while they without science knew how to live; and that I understood, but I could not understand their knowledge.

- IV

- They showed me their trees, and I could not understand the intense love with which they looked at them; it was as though they were talking with creatures like themselves. And perhaps I shall not be mistaken if I say that they conversed with them. Yes, they had found their language, and I am convinced that the trees understood them. They looked at all Nature like that — at the animals who lived in peace with them and did not attack them, but loved them, conquered by their love. They pointed to the stars and told me something about them which I could not understand, but I am convinced that they were somehow in touch with the stars, not only in thought, but by some living channel.

- IV

- They had no temples, but they had a real living and uninterrupted sense of oneness with the whole of the universe; they had no creed, but they had a certain knowledge that when their earthly joy had reached the limits of earthly nature, then there would come for them, for the living and for the dead, a still greater fullness of contact with the whole of the universe. They looked forward to that moment with joy, but without haste, not pining for it, but seeming to have a foretaste of it in their hearts, of which they talked to one another.

- IV

- They sang the praises of nature, of the sea, of the woods. They liked making songs about one another, and praised each other like children; they were the simplest songs, but they sprang from their hearts and went to one's heart. And not only in their songs but in all their lives they seemed to do nothing but admire one another. It was like being in love with each other, but an all-embracing, universal feeling.

- IV

- Oh, everyone laughs in my face now, and assures me that one cannot dream of such details as I am telling now, that I only dreamed or felt one sensation that arose in my heart in delirium and made up the details myself when I woke up. And when I told them that perhaps it really was so, my God, how they shouted with laughter in my face, and what mirth I caused! Oh, yes, of course I was overcome by the mere sensation of my dream, and that was all that was preserved in my cruelly wounded heart; but the actual forms and images of my dream, that is, the very ones I really saw at the very time of my dream, were filled with such harmony, were so lovely and enchanting and were so actual, that on awakening I was, of course, incapable of clothing them in our poor language, so that they were bound to become blurred in my mind; and so perhaps I really was forced afterwards to make up the details, and so of course to distort them in my passionate desire to convey some at least of them as quickly as I could. But on the other hand, how can I help believing that it was all true? It was perhaps a thousand times brighter, happier and more joyful than I describe it. Granted that I dreamed it, yet it must have been real. You know, I will tell you a secret: perhaps it was not a dream at all!

- IV

- How it could come to pass I do not know, but I remember it clearly. The dream embraced thousands of years and left in me only a sense of the whole. I only know that I was the cause of their sin and downfall. Like a vile trichina, like a germ of the plague infecting whole kingdoms, so I contaminated all this earth, so happy and sinless before my coming. They learnt to lie, grew fond of lying, and discovered the charm of falsehood.

- V

- All became so jealous of the rights of their own personality that they did their very utmost to curtail and destroy them in others, and made that the chief thing in their lives. Slavery followed, even voluntary slavery; the weak eagerly submitted to the strong, on condition that the latter aided them to subdue the still weaker. Then there were saints who came to these people, weeping, and talked to them of their pride, of their loss of harmony and due proportion, of their loss of shame. They were laughed at or pelted with stones.

- V

- Alas! I always loved sorrow and tribulation, but only for myself, for myself; but I wept over them, pitying them. I stretched out my hands to them in despair, blaming, cursing and despising myself. I told them that all this was my doing, mine alone; that it was I had brought them corruption, contamination and falsity. I besought them to crucify me, I taught them how to make a cross. I could not kill myself, I had not the strength, but I wanted to suffer at their hands. I yearned for suffering, I longed that my blood should be drained to the last drop in these agonies. But they only laughed at me, and began at last to look upon me as crazy. They justified me, they declared that they had only got what they wanted themselves, and that all that now was could not have been otherwise. At last they declared to me that I was becoming dangerous and that they should lock me up in a madhouse if I did not hold my tongue. Then such grief took possession of my soul that my heart was wrung, and I felt as though I were dying; and then . . . then I awoke.

- V

- I go to spread the tidings, I want to spread the tidings — of what? Of the truth, for I have seen it, have seen it with my own eyes, have seen it in all its glory.

- V

- I have seen the truth; I have seen and I know that people can be beautiful and happy without losing the power of living on earth. I will not and cannot believe that evil is the normal condition of mankind. And it is just this faith of mine that they laugh at. But how can I help believing it? I have seen the truth — it is not as though I had invented it with my mind, I have seen it, seen it, and the living image of it has filled my soul for ever. I have seen it in such full perfection that I cannot believe that it is impossible for people to have it.

- V

- A dream! What is a dream? And is not our life a dream? I will say more. Suppose that this paradise will never come to pass (that I understand), yet I shall go on preaching it. And yet how simple it is: in one day, in one hour everything could be arranged at once! The chief thing is to love others like yourself, that's the chief thing, and that's everything; nothing else is wanted — you will find out at once how to arrange it all. And yet it's an old truth which has been told and retold a billion times — but it has not formed part of our lives! The consciousness of life is higher than life, the knowledge of the laws of happiness is higher than happiness — that is what one must contend against. And I shall. If only everyone wants it, it can be arranged at once.

- V

The Brothers Karamazov (1879–1880)

edit- A man who lies to himself, and believes his own lies, becomes unable to recognize truth, either in himself or in anyone else, and he ends up losing respect for himself and for others. When he has no respect for anyone, he can no longer love, and in him, he yields to his impulses, indulges in the lowest form of pleasure, and behaves in the end like an animal in satisfying his vices. And it all comes from lying — to others and to yourself.

- Variant translations:

- Above all, do not lie to yourself. A man who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to a point where he does not discern any truth either in himself or anywhere around him, and thus falls into disrespect towards himself and others. Not respecting anyone, he ceases to love, and having no love, he gives himself up to passions and coarse pleasures, in order to occupy and amuse himself, and in his vices reaches complete bestiality, and it all comes from lying continually to others and to himself. A man who lies to himself is often the first to take offense. It sometimes feels very good to take offense, doesn't it? And surely he knows that no one has offended him, and that he himself has invented the offense and told lies just for the beauty of it, that he has exaggerated for the sake of effect, that he has picked on a word and made a mountain out of a pea — he knows all of that, and still he is the first to take offense, he likes feeling offended, it gives him great pleasure, and thus he reaches the point of real hostility... Do get up from your knees and sit down, I beg you, these posturings are false, too.

- Part I, Book I: A Nice Little Family, Ch. 2 : The Old Buffoon; as translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, p. 44

- There is no sin, and there can be no sin on all the earth, which the Lord will not forgive to the truly repentant! Man cannot commit a sin so great as to exhaust the infinite love of God. Can there be a sin which could exceed the love of God?

- Book II, ch. 3 (trans. Constance Garnett)

- The Elder Zossima, speaking to a devout widow afraid of death

- If you are penitent, you love. And if you love you are of God. All things are atoned for, all things are saved by love. If I, a sinner even as you are, am tender with you and have pity on you, how much more will God have pity upon you. Love is such a priceless treasure that you can redeem the whole world by it, and cleanse not only your own sins but the sins of others.

- Book II, ch. 3 (trans. Constance Garnett)

- The Elder Zossima, speaking to a devout widow afraid of death

- If I seem happy to you . . . You could never say anything that would please me more. For men are made for happiness, and anyone who is completely happy has a right to say to himself, 'I am doing God's will on earth.' All the righteous, all the saints, all the holy martyrs were happy.

- Book II, ch. 4 (trans. Constance Garnett)

- "It's just the same story as a doctor once told me," observed the elder. "He was a man getting on in years, and undoubtedly clever. He spoke as frankly as you, though in jest, in bitter jest. 'I love humanity,' he said, 'but I wonder at myself. The more I love humanity in general, the less I love man in particular. In my dreams,' he said, 'I have often come to making enthusiastic schemes for the service of humanity, and perhaps I might actually have faced crucifixion if it had been suddenly necessary; and yet I am incapable of living in the same room with any one for two days together, as I know by experience. As soon as any one is near me, his personality disturbs my self-complacency and restricts my freedom. In twenty-four hours I begin to hate the best of men: one because he's too long over his dinner; another because he has a cold and keeps on blowing his nose. I become hostile to people the moment they come close to me. But it has always happened that the more I detest men individually the more ardent becomes my love for humanity.'"

- Book II, ch. 4 (trans. Constance Garnett)

- The Elder Zossima, speaking to Mrs. Khoklakov

- Above all, avoid falsehood, every kind of falsehood, especially falseness to yourself. Watch over your own deceitfulness and look into it every hour, every minute.

- Book II, ch. 4 (trans. Constance Garnett)

- The Elder Zossima, speaking to Mrs. Khoklakov

- If you were to destroy in mankind the belief in immortality, not only love but every living force maintaining the life of the world would at once be dried up. Moreover, nothing then would be immoral, everything would be lawful, even cannibalism.

- Book II, ch. 6 (trans. Constance Garnett)

- Pyotr Miusov, summarizing an argument made by Ivan at a social gathering

- Fathers and teachers, what is the monk? In the cultivated world the word is nowadays pronounced by some people with a jeer, and by others it is used as a term of abuse, and this contempt for the monk is growing. It is true, alas, it is true, that there are many sluggards, gluttons, profligates and insolent beggars among monks. Educated people point to these: “You are idlers, useless members of society, you live on the labor of others, you are shameless beggars.” And yet how many meek and humble monks there are, yearning for solitude and fervent prayer in peace! These are less noticed, or passed over in silence. And how surprised men would be if I were to say that from these meek monks, who yearn for solitary prayer, the salvation of Russia will come perhaps once more! For they are in truth made ready in peace and quiet “for the day and the hour, the month and the year.” Meanwhile, in their solitude, they keep the image of Christ fair and undefiled, in the purity of God's truth, from the times of the Fathers of old, the Apostles and the martyrs. And when the time comes they will show it to the tottering creeds of the world. That is a great thought. That star will rise out of the East.

- Book VI, chapter 3: "Conversations and Exhortations of Father Zossima; The Russian Monk and his possible Significance" (translated by Constance Garnett)

- Brothers, have no fear of men's sin. Love a man even in his sin, for that is the semblance of Divine Love and is the highest love on earth. Love all God's creation, the whole of it and every grain of sand in it. Love every leaf, every ray of God's light. Love the animals, love the plants, love everything. If you love everything, you will perceive the divine mystery in things. Once you have perceived it, you will begin to comprehend it better every day, and you will come at last to love the world with an all-embracing love. Love the animals: God has given them the rudiments of thought and untroubled joy. So do not trouble it, do not harass them, do not deprive them of their joy, do not go against God's intent. Man, do not exhale yourself above the animals: they are without sin, while you in your majesty defile the earth by your appearance on it, and you leave the traces of your defilement behind you — alas, this is true of almost every one of us! Love children especially, for like the angels they too are sinless, and they live to soften and purify our hearts, and, as it were, to guide us. Woe to him who offends a child.

My young brother asked even the birds to forgive him. It may sound absurd, but it is right none the less, for everything, like the ocean, flows and enters into contact with everything else: touch one place, and you set up a movement at the other end of the world. It may be senseless to beg forgiveness of the birds, but, then, it would be easier for the birds, and for the child, and for every animal if you were yourself more pleasant than you are now. Everything is like an ocean, I tell you. Then you would pray to the birds, too, consumed by a universal love, as though in ecstasy, and ask that they, too, should forgive your sin. Treasure this ecstasy, however absurd people may think it.- Book VI, chapter 3: "Conversations and Exhortations of Father Zossima; Of Prayer, of Love, and of Contact with other Worlds" (translated by Constance Garnett)

- Нет бессмертия души, так нет и добродетели, значит, всё позволено. ... Без бога-то и без будущей жизни? Ведь это, стало быть, теперь всё позволено, всё можно делать?

- If there is no immortality, there is no virtue. ... Without God and immortal life? All things are lawful then, they can do what they like?

- Is there in the whole world a being who would have the right to forgive and could forgive? I don't want harmony. From love for humanity I don't want it. I would rather be left with the unavenged suffering. I would rather remain with my unavenged suffering and unsatisfied indignation, even if I were wrong. Besides, too high a price is asked for harmony; it's beyond our means to pay so much to enter on it. And so I hasten to give back my entrance ticket, and if I am an honest man I am bound to give it back as soon as possible. And that I am doing. It's not God that I don't accept, Alyosha, only I most respectfully return him the ticket.

- The stupider one is, the closer one is to reality. The stupider one is, the clearer one is. Stupidity is brief and artless, while intelligence wriggles and hides itself. Intelligence is a knave, but stupidity is honest and straightforward.

- Fathers and teachers, I ponder, "What is hell?" I maintain that it is the suffering of being unable to love.

- Dostoevsky (1999) [1880]. The Brothers Karamazov. Constance Garnett, translator. Signet Classic. pp. p. 312. ISBN 0451527348.

- 'But,' I [Dmitri Karamazov] asked, 'how will man be after that? Without God and the future life? It means everything is permitted now, one can do anything?' 'Didn't you know?' he said. And he laughed. 'Everything is permitted to the intelligent man,' he said.

- Book XI, ch. 4 (trans. Pevear and Volokhonsky)

- People talk sometimes of a bestial cruelty, but that's a great injustice and insult to the beasts; a beast can never be so cruel as a man, so artistically cruel. The tiger only tears and gnaws, that's all he can do. He would never think of nailing people by the ears, even if he were able to do it.

- I think the devil doesn't exist, but man has created him, he has created him in his own image and likeness.

- Beauty is a terrible and awful thing! It is terrible because it has not been fathomed, for God sets us nothing but riddles. Here the boundaries meet and all contradictions exist side by side.

- In most cases, people, even the most vicious, are much more naive and simple-minded than we assume them to be. And this is true of ourselves too.

- The awful thing is that beauty is mysterious as well as terrible. God and the devil are fighting there and the battlefield is the heart of man.

- Even those who have renounced Christianity and attack it, in their inmost being still follow the Christian ideal, for hitherto neither their subtlety nor the ardor of their hearts has been able to create a higher ideal of man and of virtue than the ideal given by Christ.

- Men reject their prophets and slay them, but they love their martyrs and honor those they have slain.

- So long as man remains free he strives for nothing so incessantly and so painfully as to find some one to worship.

- If they drive God from the earth, we shall shelter Him underground.

- Even there, in the mines, underground, I may find a human heart in another convict and murderer by my side, and I may make friends with him, for even there one may live and love and suffer. One may thaw and revive a frozen heart in that convict, one may wait upon him for years, and at last bring up from the dark depths a lofty soul, a feeling, suffering creature; one may bring forth an angel, create a hero! There are so many of them, hundreds of them, and we are to blame for them.

- My feelings, gratitude, for instance, are denied me simply because of my social position.

- The Devil (Ivan's Nightmare)

- Do you know that ages will pass and mankind will proclaim in its wisdom and science that there is no crime and, therefore no sin, but that there are only hungry people. "Feed them first and then demand virtue of them!" — that is what they will inscribe on their banner which they will raise against you and which will destroy your temple.

- To be in love is not the same as loving. You can be in love with a woman and still hate her.

- It's the great mystery of human life that old grief passes gradually into quiet tender joy.

- What terrible tragedies realism inflicts on people.'

- People talk sometimes of bestial cruelty, but that's a great injustice and insult to the beasts; a beast can never be so cruel as a man, so artistically cruel.

- Paper, they say, does not blush, but I assure you it's not true and that it's blushing just as I am now, all over.

- For socialism is not merely the labour question, it is before all things the atheistic question, the question of the form taken by atheism to-day, the question of the tower of Babel built without God, not to mount to heaven from earth but to set up heaven on earth.

- I am sorry I can say nothing more consoling to you, for love in action is a harsh and dreadful thing compared with love in dreams. Love in dreams is greedy for immediate action, rapidly performed and in the sight of all. Men will even give their lives if only the ordeal does not last long but is soon over, with all looking on and applauding as though on the stage. But active love is labour and fortitude, and for some people too, perhaps, a complete science. But I predict that just when you see with horror that in spite of all your efforts you are getting farther from your goal instead ofnearer to it — at that very moment I predict that you will reach it and behold clearly the miraculous power of the Lord who has been all the time loving and mysteriously guiding you.

- ‘No one but you and one ‘jade’ I have fallen in love with, to my ruin. But being in love doesn't mean loving. You may be in love with a woman and yet hate her.

- Beauty is a terrible and awful thing! It is terrible because it has not been fathomed and never can be fathomed, for God sets us nothing but riddles. Here the boundaries meet and all contradictions exist side by side. I am a cultivated man, brother, but I've thought a lot about this. It's terrible what mysteries there are! Too many riddles weigh men down on earth. We must solve them as we can, and try to keep a dry skin in the water. Beauty! I can't endure the thought that a man of lofty mind and heart begins with the ideal of the Madonna and ends with the ideal of Sodom. What's still more awful is that a man with the ideal of Sodom in his soul does not renounce the ideal of the Madonna, and his heart may be on fire with that ideal, genuinely on fire, just as in his days of youth and innocence. Yes, man is broad, too broad, indeed. I'd have him narrower. The devil only knows what to make of it! What to the mind is shameful is beauty and nothing else to the heart. Is there beauty in Sodom? Believe me, that for the immense mass of mankind beauty is found in Sodom. Did you know that secret? The awful thing is that beauty is mysterious as well as terrible. God and the devil are fighting there and the battlefield is the heart of man. But a man always talks of his own ache.

- So long as man remains free he strives for nothing so incessantly and so painfully as to find someone to worship. But man seeks to worship what is established beyond dispute, so that all men would agree at once to worship it. For these pitiful creatures are concerned not only to find what one or the other can worship, but to find community of worship is the chief misery of every man individually and of all humanity from the beginning of time. For the sake of common worship they've slain each other with the sword. They have set up gods and challenged one another, ‘Put away your gods and come and worship ours, or we will kill you and your gods!’ And so it will be to the end of the world, even when gods disappear from the earth; they will fall down before idols just the same.

- Why count the days, when even one days is enough for a man to know all happiness?

- For everyone strives to keep his individuality as apart as possible, wishes to secure the greatest possible fullness of life for himself; but meantime all his efforts result not in attaining fullness of life but self-destruction, for instead of self-realisation he ends by arriving at complete solitude. All mankind in our age have split up into units, they all keep apart, each in his own groove; each one holds aloof, hides himself and hides what he has, from the rest, and he ends by being repelled by others and repelling them. He heaps up riches by himself and thinks, ‘How strong I am now and how secure,’ and in his madness he does not understand that the more he heaps up, the more he sinks into self-destructive impotence. For he is accustomed to rely upon himself alone and to cut himself off from the whole; he has trained himself not to believe in the help of others, in men and in humanity, and only trembles for fear he should lose his money and the privileges that he has won for himself. Everywhere in these days men have, in their mockery, ceased to understand that the true security is to be found in social solidarity rather than in isolated individual effort. But this terrible individualism must inevitably have an end, and all will suddenly understand how unnaturally they are separated from one another. It will be the spirit of the time, and people will marvel that they have sat so long in darkness without seeing the light.

- Faith is not in power but in truth.

Quotes about The Brothers Karamazov

edit- Ivan Karamazov ... does not absolutely deny the existence of God. He refutes Him in the name of a moral value. ... God, in His turn, is put on trial. If evil is essential to divine creation, then creation is unacceptable. Ivan will no longer have recourse to this mysterious God, but to a higher principle – namely, justice. He launches the essential undertaking of rebellion, which is that of replacing the reign of grace by the reign of justice.

- Albert Camus, The Rebel, A. Bower, trans. (1956), pp. 55-56

- Ivan is the incarnation of the refusal to be the only one saved. He throws in his lot with the damned and, for their sake, rejects eternity. If he had faith, he could, in fact, be saved, but others would be damned and suffering would continue. There is no possible salvation for the man who feels real compassion.

- Albert Camus, The Rebel, A. Bower, trans. (1956), pp. 56-57

- Throughout the nineteenth century you can find writers using brothers and sisters as ways of projecting different aspects of the single composite self. The most famous example is the Brothers Karamazov, who, with their differing emphases on body, mind and spirit, seem to be the three parts of one total individual – the collective son of their father, perhaps Man himself.

- Tony Tanner (11 September 2007). Jane Austen. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-137-06457-8.

- The Brothers Karamazov is the most magnificent novel ever written; the episode of the Grand Inquisitor, one of the peaks in the literature of the world, can hardly be valued too highly.

- Sigmund Freud, "Dostoevsky and Parricide" (1928)

- The Brothers Karamazov is a joyful book. Readers who know what it is about may find this an intolerably whimsical statement. It does have moments of joy, but they are only moments; the rest is greed, lust, squalor, unredeemed suffering, and a sometimes terrifying darkness. But the book is joyful in another sense: in its energy and curiosity, in its formal inventiveness, in the mastery of its writing

- Richard Pevear Introduction to 1992 translation

Misattributed

edit- The darker the night, the brighter the stars, the deeper the grief, the closer is God!

- Attributed to Dostoyevsky's Crime and Punishment in self-help books and on social media. The words are from an untitled poem (dated 1878) by the 19th century Russian poet Apollon Maykov. The full quatrain goes: "Не говори, что нет спасенья, / Что ты в печалях изнемог: / Чем ночь темней, тем ярче звезды, / Чем глубже скорбь, тем ближе Бог."

- Trust no one in whom the desire to punish is strong

- Variants of such a statement have also been attributed to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Nietzsche, but the only definite source found for any is in Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra: "Distrust all in whom the impulse to punish is powerful!"

- Tolerance will reach such a level that intelligent people will be banned from thinking so as not to offend the imbeciles.

- Though attributed to Dostoevsky on social media, there is no record of him making such a statement.

- The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.

- Alleged to be from House of the Dead, but no such quotation is present.

Quotes about Dostoevsky

edit- I belong to the first generation of Latin American writers brought up reading other Latin American writers...Many Russian novelists influenced me as well: Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov, Nabokov, Gogol, and Bulgarov.

- You read something which you thought only happened to you, and you discover that it happened 100 years ago to Dostoyevsky. This is a very great liberation for the suffering, struggling person, who always thinks that he is alone. This is why art is important. Art would not be important if life were not important, and life is important.

- "An interview with James Baldwin" (1961)

- You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was Dostoevsky and Dickens who taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who ever had been alive. Only if we face these open wounds in ourselves can we understand them in other people. An artist is a sort of emotional or spiritual historian. His role is to make you realize the doom and glory of knowing who you are and what you are. He has to tell, because nobody else can tell, what it is like to be alive.

- James Baldwin in "Doom and glory of knowing who you are" by Jane Howard, in LIFE magazine, Vol. 54, No. 21 (24 May 1963)

- The following is an extract from M. Dostoevsky's celebrated novel, The Brothers Karamazof, the last publication from the pen of the great Russian novelist, who died a few months ago, just as the concluding chapters appeared in print. Dostoevsky is beginning to be recognized as one of the ablest and profoundest among Russian writers. His characters are invariably typical portraits drawn from various classes of Russian society, strikingly life-like and realistic to the highest degree. The following extract is a cutting satire on modern theology generally and the Roman Catholic religion in particular. The idea is that Christ revisits earth, coming to Spain at the period of the Inquisition, and is at once arrested as a heretic by the Grand Inquisitor.

- H.P. Blavatsky in the Foreword of The Grand Inquisitor, The Theosophist (November-December 1881)

- In the preface to an anthology of Russian literature, Vladimir Nabokov stated that he had not found a single page of Dostoevsky worthy of inclusion. This ought to mean that Dostoevsky should not be judged by each page but rather by the total of all the pages that comprise the book.

- Jorge Luis Borges, in his Preface to Dostoevsky's Demons as translated by Eliot Weinberger, in Borges's "A Personal Library" series; included in Jorge Luis Borges – Selected Non-Fictions (1999)

- The real 19th century prophet was Dostoevsky, not Karl Marx.

- I think the first discovery I made for myself which I didn't necessarily share with my family or my friends, but came upon myself, was Russian literature. I've always felt very much enthralled to writers like Dostoevsky, especially, and Chekhov.

- Anita Desai In Interviews with Writers of the Post-Colonial World edited by Feroza Jussawalla and Reed Way Dasenbrock (1992)

- Hostile portrayals of Jews are scattered throughout the writings of Fyodor Dostoyevski

- Four facets may be distinguished in the rich personality of Dostoevsky: the creative artist, the neurotic, the moralist and the sinner. How is one to find one's way in this bewildering complexity?

- Sigmund Freud, "Dostoevsky and Parricide" (1928)

- When I was working on China Men, I remember reading a critic who was praising the great male writers, like Flaubert and Tolstoy and Dostoevsky and Henry James, who were able to write great women characters. I don't remember if they said women had done men in this way or not, but I remember thinking that to finish myself as a great artist I'd have to be able to create men characters. Along with that, I was thinking that I had to do more than the first person pronoun.

- 1991 interview in Conversations with Maxine Hong Kingston (1998)

- (Who are some of the writers you enjoy reading and re-reading?) SK: Dostoevsky and Simon De Beauvoir. Since I was a young teenager, I started reading them and I never stopped. From Dostoevsky, I learned how characters are made or should be. How they move, what they think, their inner secrets, their contradictions and complications, and how strong and helpless they are. I am fascinated by most of his work, especially Brothers Karamazov...Those two writers affected me deeply.

- Sahar Khalifeh Interview (2021)

- I was soaked in the Russian novels from the age of fourteen on. I read and reread Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, and it's obvious to anyone who's familiar with their work that I've been tremendously influenced by them.

- 1982 interview in Conversations with Ursula Le Guin (2008)

- Even Dostoyevski, the great seer, the highest point of the nineteenth century, could not ward off the devils that prompted him to abandon the ecumenical idea in favor of national exclusiveness.

- Nadezhda Mandelstam Hope Abandoned (1974) Translated from the Russian by Max Hayward

- We reread Dostoyevski together in Tashkent and were struck both by his prophetic insights and by his incredible lapses as a publicist: his hatred of Catholicism, his cheap nationalism, and his "moujik Marei." "Both of them are heresiarchs," Akhmatova used to say about Dostoyevski and Tolstoi. She compared the two greatest Russian writers to twin towers of the same building. Both of them sought salvation from imminent catastrophe, the nature of which was understood by Dostoyevski, though not by Tolstoi. In their actual proposals for salvation both of them exhibited license in the highest degree. In fact, however, not even the best of proposals would have been able to halt a process of decomposition already so far advanced. Dostoyevski the artist is incomparably more profound than Dostoyevski the publicist. In the preparatory notes for his novels one sees the publicist's mind at work.

- Nadezhda Mandelstam Hope Abandoned (1974) Translated from the Russian by Max Hayward

- The testimony of Dostoevsky is relevant to this problem — Dostoevsky, the only psychologist, incidentally, from whom I had something to learn; he ranks among the most beautiful strokes of fortune in my life, even more than my discovery of Stendhal.

- Friedrich Nietzsche in Twilight of the Idols (1889)

- Dostoevsky once wrote, "If God did not exist, everything would be permitted"; and that, for existentialism, is the starting point. Everything is indeed permitted, if God does not exist, and man is in consequence forlorn, for he cannot find anything to depend upon either within or outside himself. He discovers forthwith that he is without excuse. For if indeed existence precedes essence, one will never be able to explain one's action by reference to a given and specific human nature; in other words, there is no determinism-man is free, man is freedom.

- Jean-Paul Sartre Existentialism and Humanism, 1948 p. 33-34

- In a speech last year on women's liberation, I said how wonderful it was for us to be living in a period in which Dostoevski's statement that there was no such thing as an ugly woman was at last coming true. Of course I don't mean that absolutely and literally but I said it seriously in that speech because I was talking about the terrible Madison Avenue-contrived notions of sexual attractiveness that were imposed upon the girls of my generation and how dreadful it was to be made to think, as I did, that you had to conform to some impossible standard of advertising beauty in order to be in the sexual running at all. How can anyone of my generation do anything except celebrate the fact that this is no longer how things are?

- Diana Trilling We Must March My Darlings (1977)

- In fact, the real problem with the thesis of A Genealogy of Morals is that the noble and the aristocrat are just as likely to be stupid as the plebeian. I had noted in my teens that major writers are usually those who have had to struggle against the odds -- to "pull their cart out of the mud," as I put it -- while writers who have had an easy start in life are usually second rate -- or at least, not quite first-rate. Dickens, Balzac, Dostoevsky, Shaw, H. G. Wells, are examples of the first kind; in the twentieth century, John Galsworthy, Graham Greene, Evelyn Waugh, and Samuel Beckett are examples of the second kind. They are far from being mediocre writers; yet they tend to be tinged with a certain pessimism that arises from never having achieved a certain resistance against problems.

- Colin Wilson in The Books In My Life, p. 188

External links

edit- FyodorDostoevsky.com

- FedorDostoievsky.com

- Brief biography and works at The Free Library

- Dostoevsky Research Station

- Works by Fyodor Dostoevsky at Project Gutenberg

- Dostoevsky e-texts at Penn Librarys digital library project

- Dostoyevsky 'Bookweb' at The Ledge

- Full texts of some Dostoevsky's works in the original Russian

- Another site with full texts of Dostoevsky's works in Russian

- Fyodor Dostoevsky Biography by Iolo Savill

- Alexander II and His Times: A Narrative History of Russia in the Age of Alexander II, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky

- The Gospel in Dostoevsky