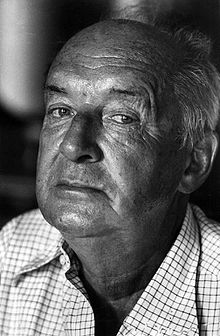

Vladimir Nabokov

Russian-American novelist, lepidopterist, professor (1899–1977)

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov (22 April (O.S. 10 April) 1899 – 2 July 1977) was a Russian-American writer. He wrote his first literary works in Russian, but gained international prominence as a masterly prose stylist for the novels he composed in English; his Lolita (1955) is frequently cited as one of the most important novels of the 20th century.

- See also:

Quotes

edit- And there are things that are hard to talk about—you'll rub off their marvelous pollen at the touch of a word.

- Letter to then-girlfriend Véra (26 July 1923); in Letters to Véra (2014), p 3.

- What is this jest in majesty? This ass in passion? How do God and Devil combine to form a live dog?

- Despair [Отчаяние (Otchayanie)] (1936).

- Dark pictures, thrones, the stones that pilgrims kiss

Poems that take a thousand years to die

But ape the immortality of this

Red label on a little butterfly.- "A Discovery" (December 1941); published as "On Discovering a Butterfly" in The New Yorker (15 May 1943); also in Nabokov's Butterflies: Unpublished and Uncollected Writings (2000) Edited and annotated by Brian Boyd and Robert Michael Pyle, p. 274.

- To know that no one before you has seen an organ you are examining, to trace relationships that have occurred to no one before, to immerse yourself in the wondrous crystalline world of the microscope, where silence reigns, circumscribed by its own horizon, a blindingly white arena — all this is so enticing that I cannot describe it.

- Letter to his sister Elena Sikorski (1945); in Nabokov's Butterflies: Unpublished and Uncollected Writings (2000) Edited and annotated by Brian Boyd and Robert Michael Pyle, p. 387.

- The clumsiest literal translation is a thousand times more useful than the prettiest paraphrase.

- Problems of translation (1955).

- Direct interference in a person's life does not enter our scope of activity, nor, on the other, tralatitiously speaking, hand, is his destiny a chain of predeterminate links: some 'future' events may be linked to others, O.K., but all are chimeric, and every cause-and-effect sequence is always a hit-and-miss affair, even if the lunette has actually closed around your neck, and the cretinous crowd holds its breath.

- Transparent Things (1972), Ch. 24.

- Play! Invent the world! Invent reality!

- Look at the Harlequins! (1974).

- I hastened to quench a thirst that had been burning a hole in the mixed metaphor of my life ever since I had fondled a quite different Dolly thirteen years earlier.

- Look at the Harlequins! (1974).

- Lolita is famous, not I. I am an obscure, doubly obscure, novelist with an unpronounceable name.

- Interview with Herbert Gold, The Paris Review Interviews: Writers at Work, 4th series (1977), p. 107 ISBN 0-140-04543-0

- Genius still means to me, in my Russian fastidiousness and pride of phrase, a unique dazzling gift. The gift of James Joyce, and not the talent of Henry James.

- As quoted in What Is the Sangha?: The Nature of Spritual Community (2001) by Sangharakshita, p. 136.

- Curiosity is insubordination in its purest form.

- As quoted in Reading Lolita in Tehran (2003) by Azar Nafisi

- I think he’s crude, I think he’s medieval, and I don’t want an elderly gentleman from Vienna with an umbrella inflicting his dreams upon me. I don’t have the dreams that he discusses in his books. I don’t see umbrellas in my dreams. Or balloons.

- On Sigmund Freud, as quoted in Sigmund Says: And Other Psychotherapists' Quotes (2006) edited by Bernard Nisenholz, p. 6 ISBN 0595396593

- Satire is a lesson, parody is a game.

- Interview with Nabokov conducted on September 25, 27, 28, 29, 1966, at Montreux, Switzerland and published in Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature, vol. VIII, no. 2, spring 1967.

- The fact that since my youth – I was 19 when I left Russia — my political creed has remained as bleak and changeless as an old gray rock. It is classical to the point of triteness. Freedom of speech, freedom of thought, freedom of art. The social or economic structure of the ideal state is of little concern to me. My desires are modest. Portraits of the head of the government should not exceed a postage stamp in size. No torture and no executions.

- Playboy 1964 interview

Speak, Memory: A Memoir (1951)

edit- U.S. title: Conclusive Evidence: A Memoir

- The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness. Although the two are identical twins, man, as a rule, views the prenatal abyss with more calm than the one he is heading for (at some forty-five hundred heartbeats an hour).

- Her intense and pure religiousness took the form of her having equal faith in the existence of another world and in the impossibility of comprehending it in terms of earthly life. All one could do was to glimpse, amid the haze and the chimeras, something real ahead, just as persons endowed with an unusual persistence of diurnal cerebration are able to perceive in their deepest sleep, somewhere beyond the throes of an entangled and inept nightmare, the ordered reality of the waking hour.

- Whenever in my dreams, I see the dead, they always appear silent, bothered, strangely depressed, quite unlike their dear bright selves. I am aware of them, without any astonishment, in surroundings they never visited during their earthly existence, in the house of some friend of mine they never knew. They sit apart, frowning at the floor, as if death were a dark taint, a shameful family secret. It is certainly not then — not in dreams — but when one is wide awake, at moments of robust joy and achievement, on the highest terrace of consciousness, that mortality has a chance to peer beyond its own limits, from the mast, from the past and its castle-tower. And although nothing much can be seen through the mist, there is somehow the blissful feeling that one is looking in the right direction.

- A sense of security, of well-being, of summer warmth pervades my memory. That robust reality makes a ghost of the present. The mirror brims with brightness; a bumblebee has entered the room and bumps against the ceiling. Everything is as it should be, nothing will ever change, nobody will ever die.

Bend Sinister (1963)

edit- The term "bend sinister" means a heraldic bar or band drawn from the left side (and popularly, but incorrectly, supposed to denote bastardy). This choice of title was an attempt to suggest an outline broken by refraction, a distortion in the mirror of being, a wrong turn taken by life, a sinistral and sinister world. The title's drawback is that a solemn reader looking for "general ideas" or "human interest" (which is much the same thing) in a novel may be led to look for them in this one.

- p. vi.

- In this crazy mirror of terror and art a pseudo-quotation made up of obscure Shakespeareanisms (Chapter Three) somehow produces, despite its lack of literal meaning, the blurred diminutive image of the acrobatic performance that so gloriously supplies the bravura ending for the next chapter.

- p. x.

- An old Russian lady who has for some obscure reason begged me not to divulge her name, happened to show me in Paris the diary she had kept in the past. .... I cannot see any real necessity of complying with her anonymity. That she will ever read this book seems wildly improbable. Her name was and is Olga Olegovna Orlova — an egg-like alliteration which it would have been a pity to whithold.

Her dry account cannot convey to the untravelled reader the implied delights of a winter day such as she describes in St. Petersburg; the pure luxury of a cloudless sky designed not to warm the flesh, but solely to please the eye; the sheen of sledge-cuts on the hard-beaten snow of spacious streets with a tawny tinge about the middle tracks due to a rich mixture of horse-dung; the brightly coloured bunch of toy-balloons hawked by an aproned pedlar; the soft curve of a cupola, its gold dimmed by the bloom of powdery frost; the birch trees in the public gardens, every tiniest twig outlined white; the rasp and twinkle of winter traffic… and by the way how queer it is when you look at an old picture postcard (like the one I have placed on my desk to keep the child of memory amused for the moment) to consider the haphazard way Russian cabs had of turning whenever they liked, anywhere and anyhow, so that instead of the straight , self-conscious stream of modern traffic one sees — on this painted photograph — a dream-wide street with droshkies all awry under incredibly blue skies, which farther away, melt automatically into a pink flush of mnemonic banality.- p. 5.

- These are just a few sample quotes; for more quotes see Lolita - for a study guide see the wikibook entry for Lolita.

- Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta. She was Lo, plain Lo, in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock. She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dolores on the dotted line. But in my arms she was always Lolita. Did she have a precursor? She did, indeed she did. In point of fact, there might have been no Lolita at all had I not loved, one summer, an initial girl-child. In a princedom by the sea. Oh when? About as many years before Lolita was born as my age was that summer. You can always count on a murderer for fancy prose style. Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, exhibit number one is what the seraphs, the misinformed, simple, noble-winged seraphs, envied. Look at this tangle of thorns.

- Opening lines.

- Oh, my Lolita, I have only words to play with!

On a Book Entitled Lolita (1956)

edit- This was written as an "Afterword" to Lolita which has been used in all later editions; for more see Lolita.

- After Olympia Press, in Paris, published the book, an American critic suggested that Lolita was the record of my love affair with the romantic novel. The substitution "English language" for "romantic novel" would make this elegant formula more correct.

- As quoted in "Nabokov's Love Affairs" by R. W. Flint in The New Republic (17 June 1957).

- As far as I can recall, the initial shiver of inspiration was somehow prompted by a newspaper story about an ape in the Jardin des Plantes who, after months of coaxing by a scientist, produced the first drawing ever charcoaled by an animal: this sketch showed the bars of the poor creature's cage.

- As quoted at Penn State University Libraries.

- The heating system was a farce, depending as it did on registers in the floor wherefrom the tepid exhalations of a throbbing and groaning basement furnace were transmitted to the rooms with the faintness of a moribund's last breath.

- I was the shadow of the waxwing slain

by the false azure in the windowpane;

- No free man needs a God; but was I free?

- What moment in that gradual decay

- Does resurrection choose? What year?

- Who has the stopwatch? Who rewinds the tape?

- Are some less lucky, or do all escape?

- A syllogism; other men die

- But I am not another: therefore I'll not die.

- For we die every day; oblivion thrives

- Not on dry thighbones but on blood-ripe lives,

- And our best yesterdays are now foul piles

- Of crumpled names, phone numbers and foxed files.

- You have hal...... real bad, chum.

- Solitude is the playfield of Satan.

- "What!" cried Bretwit in candid surprise, "They know at home that His Majesty has left Zembla?"

- True art is above false honor.

- We can at last describe his tie, an Easter gift from a dressy butcher, his brother in law in Onhava: imitation silk, colour chocolate brown barred with red, the end tucked into the shirt between the second and third buttons - a Zemblan fashion of the nineteen thirties.

- This brand of paper (used by macaroon makers) was not only digestible but delicious.

- I certainly do speak Russian. You see, it was the fashionable language par excellence, much more than French, among the nobles of Zembla at least.

- In due time history will have denounced everybody.

- But no aorta could report regret.

- A sun of rubber was convulsed and set;

- And blood-black nothingness began to spin

- A system of cells interlinked within

- Cells interlinked within cells interlinked

- Within one stem. And dreadfully distinct

- Against the dark, a tall white fountain played.

- Quoted in dialogue in the movie Blade Runner 2049

Strong Opinions (1973)

edit- My loathings are simple: stupidity, oppression, crime, cruelty, soft music. My pleasures are the most intense known to man: writing and butterfly hunting.

- "Foreword", p. 3.

- I don't think in any language. I think in images. I don't believe that people think in languages. They don't move their lips when they think. It is only a certain type of illiterate person who moves his lips as he reads or ruminates. No, I think in images, and now and then a Russian phrase or an English phrase will form with the foam of the brainwave, but that’s about all.

- From a BBC Interview (1962), p. 14.

- I don't belong to any club or group. I don't fish, cook, dance, endorse books, sign books, co-sign declarations, eat oysters, get drunk, go to church, go to analysts, or take part in demonstrations.

- p. 18.

- To be quite candid — and what I am going to say now is something I have never said before, and I hope that it provokes a salutary chill — I know more than I can express in words, and the little I can express would not have been expressed, had I not known more.

- p. 45

- To return to my lecturing days: I automatically gave low marks when a student used the dreadful phrase "sincere and simple" — "Flaubert writes with a style which is always simple and sincere" — under the impression that this was the greatest compliment payable to prose or poetry. When I struck the phrase out, which I did with such rage that it ripped the paper, the student complained that this was what teachers had always taught him: "Art is simple, art is sincere." Someday I must trace this vulgar absurdity to its source. A schoolmarm in Ohio? A progressive ass in New York? Because, of course, art at its greatest is fantastically deceitful and complex.

- p. 32.

- Let the credulous and the vulgar continue to believe that all mental woes can be cured by a daily application of old Greek myths to their private parts.

- On the ideas of Sigmund Freud, p. 66.

- Oh, "impressed" is not the right word! Treading the soil of the moon gives one, I imagine (or rather my projected self imagines), the most remarkable romantic thrill ever experienced in the history of discovery. Of course, I rented a television set to watch every moment of their marvelous adventure. That gentle little minuet that despite their awkward suits the two men danced with such grace to the tune of lunar gravity was a lovely sight. It was also a moment when a flag means to one more than a flag usually does. I am puzzled and pained by the fact that the English weeklies ignored the absolutely overwhelming excitement of the adventure, the strange sensual exhilaration of palpating those precious pebbles, of seeing our marbled globe in the black sky, of feeling along one's spine the shiver and wonder of it. After all, Englishmen should understand that thrill, they who have been the greatest, the purest explorers. Why then drag in such irrelevant matters as wasted dollars and power politics?

- On the first moon landing, p. 150.

Lectures on Literature (1980)

edit- The good reader is one who has imagination, memory, a dictionary, and some artistic sense—which sense I propose to develop in myself and in others whenever I have the chance ("Good Readers and Good Writers", p. 3).

- Curiously enough, one cannot read a book: one can only reread it. A good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a rereader ("Good Readers and Good Writers", p. 3).

Lectures on Russian Literature (1982)

edit- A philistine is a full-grown person whose interests are of a material and commonplace nature, and whose mentality is formed of the stock ideas and conventional ideals of his or her group and time. I have said "full-grown person" because the child or the adolescent who may look like a small philistine is only a small parrot mimicking the ways of confirmed vulgarians, and it is easier to be a parrot than to be a white heron. "Vulgarian" is more or less synonymous with "philistine": the stress in a vulgarian is not so much on the conventionalism of a philistine as on the vulgarity of some of his conventional notions. I may also use the terms genteel and bourgeois. Genteel implies the lace-curtain refined vulgarity which is worse than simple coarseness. To burp in company may be rude, but to say "excuse me" after a burp is genteel and thus worse than vulgar. The term bourgeois I use following Flaubert, not Marx. Bourgeois in Flaubert's sense is a state of mind, not a state of pocket. A bourgeois is a smug philistine, a dignified vulgarian.

- Philistinism implies not only a collection of stock ideas but also the use of set phrases, clichés, banalities expressed in faded words. A true philistine has nothing but these trivial ideas of which he entirely consists.

- The character I have in view when I say "smug vulgarian" is, thus, not the part-time philistine, but the total type, the genteel bourgeois, the complete universal product of triteness and mediocrity. He is the conformist, the man who conforms to his group, and he also is typified by something else: he is a pseudo-idealist, he is pseudo-compassionate, he is pseudo-wise. The fraud is the closest ally of the true philistine. All such great words as "Beauty," "Love," "Nature," "Truth," and so on become masks and dupes when the smug vulgarian employs them. ... The philistine likes to impress and he likes to be impressed, in consequence of which a world of deception, of mutual cheating, is formed by him and around him.

- The rich philistinism emanating from advertisements is due not to their exaggerating (or inventing) the glory of this or that serviceable article but to suggesting that the acme of human happiness is purchasable and that its purchase somehow ennobles the purchaser.

Quotes about Nabokov or his work

edit- Following Nabokov's earlier excellent, offbeat novels (including Pnin, TIME, March 18, 1957), Lolita should give his name its true dimensions and expose a wider U.S. public to his special gift — which is to deal with life as if it were a thing created by a mad poet on a spring night.

- I belong to the first generation of Latin American writers brought up reading other Latin American writers...Many Russian novelists influenced me as well: Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov, Nabokov, Gogol, and Bulgarov.

- All of Nabokov's books are about tyranny, even Lolita. Perhaps Lolita most of all.

- Martin Amis in Koba the Dread: Laughter and the Twenty Million (2002).

- Lolita is pornography, and we do not plan to review it.

- Frederic Babcock, editor of the Chicago Tribune Magazine of Books as quoted in "The Lolita Case" in TIME magazine (17 November 1958).

- He can write, but he's got nothing to say.

- Soviet novelist Isaac Babel as quoted in Memoirs: 1921-1941 (1964) by Ilya Ehrenburg, page 110.

- Nabakov wrote on index cards,

at a lectern, in his socks.

- (The last book you read that made you furious?) Nabokov’s lecture on Jane Austen documented in “Vladimir Nabokov: Lectures on Literature,” edited by Fredson Bowers. In a letter to Edmund Wilson, Nabokov wrote: “I dislike Jane, and am prejudiced, in fact, against all women writers. They are in another class.” There’s pride and prejudice for you!

- Sandra Cisneros interview (2021)

- (F.J.: You put Nabokov in the category of American literature?) Desai: Of necessity, yes. I have a feeling probably he himself saw himself as an American writer. After all, he deliberately began to write in English-abandoned Russian and wrote in English. I think his richest novels are the very earliest ones, which he wrote in Russian. But I reread Lolita recently and it seemed to me a masterpiece, and it's an American masterpiece.

- Anita Desai In Interviews with Writers of the Post-Colonial World edited by Feroza Jussawalla and Reed Way Dasenbrock (1992)

- Gentlemen, even if one allows that he is an important writer, are we next to invite an elephant to be Professor of Zoology?

- Roman Jakobson declining VN a position at Harvard in 1957 (The Garland Companion to Vladimir Nabokov Vladimir E. Alexandrov (editor). Garland Publishing, New York and London (1995), ISNB 0-8153-0354-8, page xlv).

- Vladimir Nabokov-to me, his is not a good prose style. It is self-conscious, self-reflective, rather posturing, goes in for a lot of fancy vocabulary; it is always bringing me up short. I want to say, "Oh, stop showing off, Vladimir, get on with it."

- 1988 interview in Conversations with Ursula Le Guin

- I don't like Nabokov. I'm told I have to read Ada because it's a science fiction novel, but I can't read it. Boring.

- 1982 interview in Conversations with Ursula Le Guin

- there are two authors I consider my teachers, one on the most realistic side and the other one in the most fantastic side: ...Ursula K. Le Guin...and Nabokov

- Rosa Montero Interview with rain taxi (2017), Translated from the Spanish by Jorge Armenteros

- I think some of the greatest writing has been also about writers like Conrad or Nabokov, who have illuminated and given us fresh views about the new countries they adopted. Nabokov's best work was about America, and it was written during his period of exile in this country and later in Switzerland. And I think he could see this America through the eyes of his Russia. And even Russian language glimmers through those amazingly light field scenes in Lolita or his other works. So it is not just that other country that comes to us. This new country is also nourished because language is also a home. And when you change that home and come to a new thing, you'd love to play with it.

- Azar Nafisi 2010 interview included in Conversations with Edwidge Danticat edited by Maxine Lavon Montgomery (2017)

- Lolita is one of our finest American novels, a triumph of style and vision, an unforgettable work, Nabokov's best (though not most characteristic) work, a wedding of Swiftian satirical vigor with the kind of minute, loving patience that belongs to a man infatuated with the visual mysteries of the world.

- Joyce Carol Oates in "A Personal View of Nabokov" in Saturday Review of the Arts (January 1973).

- Lolita is a fine book, a distinguished book — all right then — a great book.

- Dorothy Parker's review in Esquire, as quoted in "The Lolita Case" in TIME magazine (17 November 1958).

- The political barbarism of the century made him an exile, a wanderer, a Hotelmensch, not only from his Russian homeland but from the matchless Russian tongue in which his genius would have found its unforced idiom... But I have no hesitation in arguing that this poly-linguistic matrix is the determining fact of Nabokov's life and art. But whereas so many other language exiles clung desperately to the artifice of their native tongue or fell silent, Nabokov moved into successive languages like a travelling potentate...

- George Steiner in Extraterritorial (1972), p. 7.

- Mr. Nabokov's story of the dehumanization of man under tyranny is, after all, a claustrophobic story. Whether or not it was the author's intention to model his prose system on the social system he is attacking, this is exactly what he has accomplished.

- Diana Trilling Reviewing the Forties (1974)

- Some say the Great American Novel is Huckleberry Finn, some say it's The Jungle, some say it's The Great Gatsby. But my vote goes to the tale with the maximum lust, hypocrisy and obsession — the view of America that could only have come from an outsider — Nabokov's Lolita. ... Those who bought "Lolita" looking for mere prurient kicks must surely have been disappointed. Lolita is dark and twisted all right, but it's also a corruptly beautiful love story of two tragically alike, id-driven souls... What makes Lolita a work of greatness isn't that its title has become ingrained in the vernacular, isn't that was a generation ahead of America in fetishizing young girls. No, it is the writing, the way Nabokov bounces around in words like the English language is a toy trunk, the sly wit, the way it's devastating and cynical and heartbreaking all at once. Poor old Dolly Haze might not have grown up very well, but Lolita forever remains a thing of timeless beauty.

- If I say that Nabokov, who was educated in England... turns out to be a master of English prose — the most extraordinary phenomenon of the kind since Conrad — this is likely to sound incredible. If I say that Nabokov is something like Proust, something like Franz Kafka, and, probably something like Gogol, I shall suggest an imitative patchwork, where Nabokov is as completely himself as any of these others — a man with a unique sensibility and a unique story to tell.

- Edmund Wilson, as quoted in "Nabokov's Love Affairs" by R. W. Flint in The New Republic (17 June 1957).

External links

edit- Brief biography at Kirjasto (Pegasos)

- Zembla at Penn State University

- Nabokov's interview in The Paris Review

- Nabokov Under Glass (New York Public Library exhibit)

- The Life and Works of Vladimir Nabokov

- 50 Years Later, Lolita Still Seduces Readers (NPR)

- "Lolita at 50 : Is Nabokov's masterpiece still shocking?" by Stephen Metcalf in Slate (19 December 2005)

- "The Lolita Question" by Cynthia Haven in Stanford Magazine (May/June 2006)

- "Vladimir Nabokov, Lepidopterist" by S. Abbas Raza

- "The Gay Nabokov" - essay about Nabokov's brother Sergei by Lev Grossman

- Nabokov Museum, Saint Petersburg