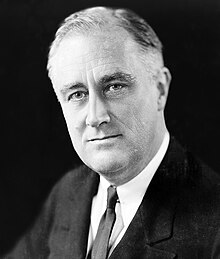

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (30 January 1882 – 12 April 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American statesman and political leader who served as the president of the United States, from 1933, to 1945. A Democrat, he won a record four presidential elections and dominated his party for many years as a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic depression and total war. His program for relief, recovery and reform, known as the New Deal, involved a great expansion of the role of the federal government in the economy.

As a dominant leader of the Democratic Party, he built the New Deal Coalition that brought together and united labor unions, big city machines, white ethnics, African Americans, and rural white Southerners in support of the party. The Coalition significantly realigned American politics after 1932, creating the Fifth Party System and defining American liberalism throughout the middle third of the 20th century. He was married to Eleanor Roosevelt.

Quotes

edit1880s

edit- Dear Sallie: I am very sorry you have a cold and you are in bed. I played with Mary today for a little while. I hope by tomorrow you will be able to be up. I am glad today [sic] that my cold is better. Your loving, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

- Roosevelt's first letter, written at age five to his mother Sara Roosevelt ("Sallie") who had been ill in her room at Hyde Park. She later supplied the date - "1887" - on beginning her collection.

- F.D.R. : His Personal Letters, Early Years (2005), edited by Elliott Roosevelt, p. 6]

1910s

edit- I sometimes think we consider too much the good luck of the early bird and not enough the bad luck of the early worm.

- Roosevelt to Henry M. Heymann (2 December 1919), as quoted in Roosevelt and Howe (1962), by Alfred B. Rollins, Jr., p. 153

- Competition has been shown to be useful up to a certain point and no further, but cooperation, which is the thing we must strive for today, begins where competition leaves off.

- Speech at the People's Forum in Troy, New York (March 3, 1912)

1920s

edit- Let us first examine that nightmare to many Americans, especially our friends in California, the growing population of Japanese on the Pacific slope. It is undoubtedly true that in the past many thousands of Japanese have legally or otherwise got into the United States, settled here and raised up children who became American citizens. Californians have properly objected on the sound basic ground that Japanese immigrants are not capable of assimilation into the American population. If this had throughout the discussion been made the sole ground for the American attitude all would have been well, and the people of Japan would today understand and accept our decision.

Anyone who has traveled in the Far East knows that the mingling of Asiatic blood with European or American blood produces, in nine cases out of ten, the most unfortunate results. There are throughout the East many thousands of so-called Eurasians—men and women and children partly of Asiatic blood and partly of European or American blood. These Eurasians are, as a common thing, looked down on and despised, both by the European and American who reside there, and by the pure Asiatic who lives there.- Editorial for Macon Telegraph, April 30, 1925

1930s

edit- The United States Constitution has proven itself the most marvelously elastic compilation of rules of government ever written.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, radio address (March 2, 1930); reported in Public Papers of Governor Roosevelt (1930), p. 710.

- The country needs and, unless I mistake its temper, the country demands bold, persistent experimentation. It is common sense to take a method and try it: If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something. The millions who are in want will not stand by silently forever while the things to satisfy their needs are within easy reach. We need enthusiasm, imagination and the ability to face facts, even unpleasant ones, bravely. We need to correct, by drastic means if necessary, the faults in our economic system from which we now suffer. We need the courage of the young. Yours is not the task of making your way in the world, but the task of remaking the world which you will find before you. May every one of us be granted the courage, the faith and the vision to give the best that is in us to that remaking!

- Oglethorpe University Commencement Address (22 May 1932)

- I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people.

- Speech accepting the Democratic nomination for president, 1932 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Illinois (2 July 1932)

- My friends, judge me by the enemies I have made.

- Speech made on the campaign trail in Portland, Oregon (21 September 1932)

- I accuse the present Administration of being the greatest spending Administration in peacetime in all American history — one which piled bureau on bureau, commission on commission, and has failed to anticipate the dire needs or reduced earning power of the people. Bureaus and bureaucrats have been retained at the expense of the taxpayer. We are spending altogether too much money for government services which are neither practical nor necessary. In addition to this, we are attempting too many functions and we need a simplification of what the Federal government is giving the people."

- "Campaign Address on Agriculture and Tariffs at w:Sioux City, Iowa (29 September 1932)

- I regard reduction in Federal spending as one of the most important issues in this campaign. In my opinion it is the most direct and effective contribution that Government can make to business.

- Campaign Address on the Federal Budget at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (October 19, 1932), quoted in The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Volume 1, p. 809. [3][4][5]

- Let me make it clear that I do not assert that a President and the Congress must on all points agree with each other at all times. Many times in history there has been complete disagreement between the two branches of the Government, and in these disagreements sometimes the Congress has won and sometimes the President has won. But during the Administration of the present President we have had neither agreement nor a clear-cut battle.

- Campaign address before the Republican-for-Roosevelt League, New York City (3 November 1932), reported in The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1928–1932 (1938), p. 857

- I'm just afraid that I may not have the strength to do this job. After you leave me tonight, Jimmy, I am going to pray. I am going to pray that God will help me, that he will give me the strength and the guidance to do this job and to do it right. I hope that you will pray for me, too, Jimmy.

- Talking to his son James on the night of his landslide victory over Herbert Hoover (8 November 1932), as quoted in Traitor to His Class: The Privileged Life and Radical Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (2008) by H. W. Brands

- If I prove a bad president, I will also likely to prove the last president.

- Remark at the time of his first inauguration as quoted in The 168 days (1938) by Joseph Alsop and Turner Catledge, p. 15

- There seems to be no question that [Mussolini] is really interested in what we are doing and I am much interested and deeply impressed by what he has accomplished and by his evidenced honest purpose of restoring Italy.

- Comment in early 1933 about Benito Mussolini to U.S. Ambassador to Italy Breckinridge Long, as quoted in Three New Deals : Reflections on Roosevelt's America, Mussolini's Italy, and Hitler's Germany, 1933-1939 (2006) by Wolfgang Schivelbusch, p. 31

- If the country is to flourish, capital must be invested in enterprise. But those who seek to draw upon other people's money must be wholly candid regarding the facts on which the investor's judgment is asked.

- Statement on Signing the Securities Bill (27 May 1933)

- Philosophy? I am a Christian and a Democrat. That's all.

- To a reporter who asked him to define his philosophy. Quoted in Alter, Jonathan The Defining Moment: FDR's Hundred Days and the Triumph of Hope pg. 244

- In my Inaugural I laid down the simple proposition that nobody is going to starve in this country. It seems to me to be equally plain that no business which depends for existence on paying less than living wages to its workers has any right to continue in this country. By "business" I mean the whole of commerce as well as the whole of industry; by workers I mean all workers, the white collar class as well as the men in overalls; and by living wages I mean more than a bare subsistence level-I mean the wages of decent living.

- The real truth of the matter is, as you and I know, that a financial element in the larger centers has owned the Government ever since the days of Andrew Jackson — and I am not wholly excepting the Administration of W. W. The country is going through a repetition of Jackson's fight with the Bank of the United States — only on a far bigger and broader basis.

- Letter to Col. Edward Mandell House (21 November 1933); as quoted in F.D.R.: His Personal Letters, 1928-1945, edited by Elliott Roosevelt (New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1950), pg. 373

- This new generation, for example, is not content with preachings against that vile form of collective murder — lynch law-which has broken out in our midst anew. We know that it is murder, and a deliberate and definite disobedience of the Commandment, "Thou shalt not kill." We do not excuse those in high places or in low who condone lynch law.

- I don't mind telling you in confidence that I am keeping in fairly close touch with that admirable Italian gentleman.

- Comment on Benito Mussolini in 1933, as quoted in Three New Deals : Reflections on Roosevelt's America, Mussolini's Italy, and Hitler's Germany, 1933-1939 (2006) by Wolfgang Schivelbusch, p. 31

- Forests require many years to mature; consequently the long point of view is necessary if the forests are to be maintained for the good of our country. He who would hold this long point of view must realize the need of subordinating immediate profits for the sake of the future public welfare. ... A forest is not solely so many thousand board feet of lumber to be logged when market conditions make it profitable. It is an integral part of our natural land covering, and the most potent factor in maintaining Nature's delicate balance in the organic and inorganic worlds. In his struggle for selfish gain, man has often needlessly tipped the scales so that Nature's balance has been destroyed, and the public welfare has usually been on the short-weighted side. Such public necessities, therefore, must not be destroyed because there is profit for someone in their destruction. The preservation of the forests must be lifted above mere dollars and cents considerations. ... The handling of our forests as a continuous, renewable resource means permanent employment and stability to our country life.

The forests are also needed for mitigating extreme climatic fluctuations, holding the soil on the slopes, retaining the moisture in the ground, and controlling the equable flow of water in our streams. The forests are the "lungs" of our land, purifying the air and giving fresh strength to our people. Truly, they make the country more livable.

There is a new awakening to the importance of the forests to the country, and if you foresters remain true to your ideals, the country may confidently trust its most precious heritage to your safe-keeping. - http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=14913 Statement on being Awarded the Schlich Forestry Medal (29 January 1935)]

- I know at the same time that you will be sympathetic to the point of view that public psychology, and for that matter, individual psychology, cannot, because of human weakness, be attuned for long periods of time to a constant repetition of the highest note on the scale.

- Letter to Ray Stannard Baker (20 March 1935), quoted in My Own Story: From Private and Public Papers (ed. Donald Day; Little, Brown & Co. 1951), p. 239

- I hope your committee will not permit doubts as to constitutionality, however reasonable, to block the suggested legislation.

- Yes, we are on our way back — not just by pure chance, my friends, not just by a turn of the wheel, of the cycle. We are coming back more soundly than ever before because we are planning it that way. Don't let anybody tell you differently.

- Speech at the Citadel (23 October 1935)

- Human kindness has never weakened the stamina or softened the fiber of a free people. A nation does not have to be cruel to be tough.

- Speech in 1935, as quoted by Donna E. Shalala, as Secretary of Health and Human Services, in a speech to the American Public Welfare Association (27 February 1995)

- The Nation that destroys its soil destroys itself.

- Letter to all State Governors on a Uniform Soil Conservation Law (26 February 1937)); this statement has sometimes been paraphrased and prefixed to an earlier FDR statement of 29 January 1935 to read: "A nation that destroys its soils destroys itself. Forests are the lungs of our land, purifying the air and giving fresh strength to our people." Though it approximates 2 separate statements of FDR, no original document in precisely this form has been located.

- Unhappy events abroad have retaught us two simple truths about the liberty of a democratic people. The first truth is that the liberty of a democracy is not safe if the people tolerate the growth of private power to a point where it becomes stronger than their democratic State itself. That, in its essence, is fascism — ownership of government by an individual, by a group or by any other controlling private power.

The second truth is that the liberty of a democracy is not safe if its business system does not provide employment and produce and distribute goods in such a way as to sustain an acceptable standard of living. Both lessons hit home. Among us today a concentration of private power without equal in history is growing.- Simple Truths message to Congress (April 29, 1938). [6] [7]

- No democracy can long survive which does not accept as fundamental to its very existence the recognition of the rights of its minorities.

- Letter to Walter Francis White, president of the NAACP (25 June 1938)

- In this world, is the destiny of mankind controlled by some transcendental entity or law? Is it like the hand of God hovering above? At least it is true that man has no control; even over his own will.

- Address to the National Education Association (30 June 1938)

- Let us not be afraid to help each other — let us never forget that government is ourselves and not an alien power over us. The ultimate rulers of our democracy are not a President and Senators and Congressmen and Government officials but the voters of this country.

- Address at Marietta, Ohio (8 July 1938)

- A radical is a man with both feet firmly planted — in the air. A conservative is a man with two perfectly good legs who, however, has never learned to walk forward. A reactionary is a somnambulist walking backwards. A liberal is a man who uses his legs and his hands at the behest — at the command — of his head.

- Radio Address to the New York Herald Tribune Forum (26 October 1939)

- Repetition does not transform a lie into a truth.

- Radio address (26 October 1939), as reported in The Baltimore Sun (27 October 1939)

First Inaugural Address (1933)

edit- First inaugural address (4 March 1933)

- Confidence... thrives on honesty, on honor, on the sacredness of obligations, on faithful protection and on unselfish performance. Without them it cannot live.

- The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization. We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths. The measure of the restoration lies in the extent to which we apply social values more noble than mere monetary profit.

- Happiness lies not in the mere possession of money; it lies in the joy of achievement, in the thrill of creative effort.

- These dark days will be worth all they cost us if they teach us that our true destiny is not to be ministered unto but to minister to ourselves and to our fellow men.

- This is preeminently the time to speak the truth, the whole truth, frankly and boldly. Nor need we shrink from honestly facing conditions in our country today. This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself — nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance. In every dark hour of our national life a leadership of frankness and vigor has met with that understanding and support of the people themselves which is essential to victory.

- Part of this is often misquoted as "We have nothing to fear but fear itself," most notably by Martin Luther King, Jr. in his I've Been To The Mountaintop speech. Similar expressions were used in ancient times, for example by Seneca the Younger (Ep. Mor. 3.24.12): scies nihil esse in istis terribile nisi ipsum timorem ("You will understand that there is nothing dreadful in this except fear itself"), and by Michel de Montaigne: "The thing I fear most is fear", in Essays (1580), Book I, Ch. 17.

State of the Union address (1935)

edit- Second State of the Union Address (4 January 1935)

- We have undertaken a new order of things; yet we progress to it under the framework and in the spirit and intent of the American Constitution. We have proceeded throughout the Nation a measurable distance on the road toward this new order.

- Throughout the world, change is the order of the day. In every Nation economic problems, long in the making, have brought crises of many kinds for which the masters of old practice and theory were unprepared. In most Nations social justice, no longer a distant ideal, has become a definite goal, and ancient Governments are beginning to heed the call.

Thus, the American people do not stand alone in the world in their desire for change. We seek it through tested liberal traditions, through processes which retain all of the deep essentials of that republican form of representative government first given to a troubled world by the United States.- Second State of the Union Address (4 January 1935)

- We find our population suffering from old inequalities, little changed by vast sporadic remedies. In spite of our efforts and in spite of our talk, we have not weeded out the over privileged and we have not effectively lifted up the underprivileged. Both of these manifestations of injustice have retarded happiness. No wise man has any intention of destroying what is known as the profit motive; because by the profit motive we mean the right by work to earn a decent livelihood for ourselves and for our families.

We have, however, a clear mandate from the people, that Americans must forswear that conception of the acquisition of wealth which, through excessive profits, creates undue private power over private affairs and, to our misfortune, over public affairs as well. In building toward this end we do not destroy ambition, nor do we seek to divide our wealth into equal shares on stated occasions. We continue to recognize the greater ability of some to earn more than others. But we do assert that the ambition of the individual to obtain for him and his a proper security, a reasonable leisure, and a decent living throughout life, is an ambition to be preferred to the appetite for great wealth and great power.

- The lessons of history, confirmed by the evidence immediately before me, show conclusively that continued dependence upon relief induces a spiritual and moral disintegration fundamentally destructive to the national fibre. To dole out relief in this way is to administer a narcotic, a subtle destroyer of the human spirit. It is inimical to the dictates of sound policy. It is in violation of the traditions of America. Work must be found for able-bodied but destitute workers. The Federal Government must and shall quit this business of relief.

- I am not willing that the vitality of our people be further sapped by the giving of cash, of market baskets, of a few hours of weekly work cutting grass, raking leaves or picking up papers in the public parks. We must preserve not only the bodies of the unemployed from destitution but also their self-respect, their self-reliance and courage and determination. This decision brings me to the problem of what the Government should do with approximately five million unemployed now on the relief rolls.

- All work undertaken should be useful — not just for a day, or a year, but useful in the sense that it affords permanent improvement in living conditions or that it creates future new wealth for the Nation.

- The work itself will cover a wide field including clearance of slums, which for adequate reasons cannot be undertaken by private capital; in rural housing of several kinds, where, again, private capital is unable to function; in rural electrification; in the reforestation of the great watersheds of the Nation; in an intensified program to prevent soil erosion and to reclaim blighted areas; in improving existing road systems and in constructing national highways designed to handle modern traffic; in the elimination of grade crossings; in the extension and enlargement of the successful work of the Civilian Conservation Corps; in non-Federal works, mostly self-liquidating and highly useful to local divisions of Government; and on many other projects which the Nation needs and cannot afford to neglect.

Message to Congress on tax revision (1935)

edit- Message to Congress on Tax Revision (19 June 1935)

- The Joint Legislative Committee, established by the Revenue Act of 1926, has been particularly helpful to the Treasury Department. The members of that Committee have generously consulted with administrative officials, not only on broad questions of policy but on important and difficult tax cases. On the basis of these studies and of other studies conducted by officials of the Treasury, I am able to make a number of suggestions of important changes in our policy of taxation. These are based on the broad principle that if a government is to be prudent its taxes must produce ample revenues without discouraging enterprise; and if it is to be just it must distribute the burden of taxes equitably. I do not believe that our present system of taxation completely meets this test. Our revenue laws have operated in many ways to the unfair advantage of the few, and they have done little to prevent an unjust concentration of wealth and economic power.

- With the enactment of the Income Tax Law of 1913, the Federal Government began to apply effectively the widely accepted principle that taxes should be levied in proportion to ability to pay and in proportion to the benefits received. Income was wisely chosen as the measure of benefits and of ability to pay. This was, and still is, a wholesome guide for national policy. It should be retained as the governing principle of Federal taxation. The use of other forms of taxes is often justifiable, particularly for temporary periods; but taxation according to income is the most effective instrument yet devised to obtain just contribution from those best able to bear it and to avoid placing onerous burdens upon the mass of our people.

- Wealth in the modern world does not come merely from individual effort; it results from a combination of individual effort and of the manifold uses to which the community puts that effort. The individual does not create the product of his industry with his own hands; he utilizes the many processes and forces of mass production to meet the demands of a national and international market. Therefore, in spite of the great importance in our national life of the efforts and ingenuity of unusual individuals, the people in the mass have inevitably helped to make large fortunes possible. Without mass cooperation great accumulations of wealth would be impossible save by unhealthy speculation. As Andrew Carnegie put it, "Where wealth accrues honorably, the people are always silent partners." Whether it be wealth achieved through the cooperation of the entire community or riches gained by speculation — in either case the ownership of such wealth or riches represents a great public interest and a great ability to pay.

- The desire to provide security for oneself and one's family is natural and wholesome, but it is adequately served by a reasonable inheritance. Great accumulations of wealth cannot be justified on the basis of personal and family security. In the last analysis such accumulations amount to the perpetuation of great and undesirable concentration of control in a relatively few individuals over the employment and welfare of many, many others.

- Social unrest and a deepening sense of unfairness are dangers to our national life which we must minimize by rigorous methods. People know that vast personal incomes come not only through the effort or ability or luck of those who receive them, but also because of the opportunities for advantage which Government itself contributes. Therefore, the duty rests upon the Government to restrict such incomes by very high taxes.

- Furthermore, the drain of a depression upon the reserves of business puts a disproportionate strain upon the modestly capitalized small enterprise. Without such small enterprises our competitive economic society would cease. Size begets monopoly. Moreover, in the aggregate these little businesses furnish the indispensable local basis for those nationwide markets which alone can ensure the success of our mass production industries. Today our smaller corporations are fighting not only for their own local well-being but for that fairly distributed national prosperity which makes large-scale enterprise possible. It seems only equitable, therefore, to adjust our tax system in accordance with economic capacity, advantage and fact. The smaller corporations should not carry burdens beyond their powers; the vast concentrations of capital should be ready to carry burdens commensurate with their powers and their advantages.

Address at San Diego Exposition (1935)

edit- Address at San Diego Exposition, San Diego, California (2 October 1935)

- To a great extent the achievements of invention, of mechanical and of artistic creation, must of necessity, and rightly, be individual rather than governmental. It is the self-reliant pioneer in every enterprise who beats the path along which American civilization has marched. Such individual effort is the glory of America.

- The task of Government is that of application and encouragement. A wise Government seeks to provide the opportunity through which the best of individual achievement can be obtained, while at the same time it seeks to remove such obstruction, such unfairness as springs from selfish human motives. Our common life under our various agencies of Government, our laws and our basic Constitution, exist primarily to protect the individual, to cherish his rights and to make clear his just principles.

- An American Government cannot permit Americans to starve.

- It is now beyond partisan controversy that it is a fundamental individual right of a worker to associate himself with other workers and to bargain collectively with his employer. New laws, in themselves, do not bring a millennium; new laws do not pretend to prevent labor disputes, nor do they cover all industry and all labor. But they do constitute an important step toward the achievement of just and peaceable labor relations in industry.

- Several centuries ago the greatest writer in history described the two most menacing clouds that hang over human government and human society as "malice domestic and fierce foreign war." We are not rid of these dangers but we can summon our intelligence to meet them. Never was there more genuine reason for Americans to face down these two causes of fear. "Malice domestic" from time to time will come to you in the shape of those who would raise false issues, pervert facts, preach the gospel of hate, and minimize the importance of public action to secure human rights or spiritual ideals. There are those today who would sow these seeds, but your answer to them is in the possession of the plain facts of our present condition.

- This country seeks no conquest. We have no imperial designs. From day to day and year to year, we are establishing a more perfect assurance of peace with our neighbors. We rejoice especially in the prosperity, the stability and the independence of all of the American Republics. We not only earnestly desire peace, but we are moved by a stern determination to avoid those perils that will endanger our peace with the world.

- Our national determination to keep free of foreign wars and foreign entanglements cannot prevent us from feeling deep concern when ideals and principles that we have cherished are challenged. In the United States we regard it as axiomatic that every person shall enjoy the free exercise of his religion according to the dictates of his conscience. Our flag for a century and a half has been the symbol of the principles of liberty of conscience, of religious freedom and of equality before the law; and these concepts are deeply ingrained in our national character.

- It is true that other Nations may, as they do, enforce contrary rules of conscience and conduct. It is true that policies may be pursued under flags other than our own, but those policies are beyond our jurisdiction. Yet in our inner individual lives we can never be indifferent, and we assert for ourselves complete freedom to embrace, to profess and to observe the principles for which our flag has so long been the lofty symbol. As it was so well said by James Madison, over a century ago: "We hold it for a fundamental and inalienable truth that religion and the manner of discharging it can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence."

- As President of the United States I say to you most earnestly once more that the people of America and the Government of those people intend and expect to remain at peace with all the world. In the two years and a half of my Presidency, this Government has remained constant in following this policy of our own choice. At home we have preached, and will continue to preach, the gospel of the good neighbor. I hope from the bottom of my heart that as the years go on, in every continent and in every clime, Nation will follow Nation in proving by deed as well as by word their adherence to the ideal of the Americas — I am a good neighbor.

Speech to the Democratic National Convention (1936)

edit- Speech at the 1936 Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (27 June 1936)]

- It was natural and perhaps human that the privileged princes of these new economic dynasties, thirsting for power, reached out for control over government itself. They created a new despotism and wrapped it in the robes of legal sanction. In its service new mercenaries sought to regiment the people, their labor, and their property. And as a result the average man once more confronts the problem that faced the Minute Man.

- The hours men and women worked, the wages they received, the conditions of their labor — these had passed beyond the control of the people, and were imposed by this new industrial dictatorship. The savings of the average family, the capital of the small-businessmen, the investments set aside for old age — other people's money — these were tools which the new economic royalty used to dig itself in. Those who tilled the soil no longer reaped the rewards which were their right. The small measure of their gains was decreed by men in distant cities. Throughout the nation, opportunity was limited by monopoly. Individual initiative was crushed in the cogs of a great machine. The field open for free business was more and more restricted. Private enterprise, indeed, became too private. It became privileged enterprise, not free enterprise.

- For too many of us the political equality we once had won was meaningless in the face of economic inequality. A small group had concentrated into their own hands an almost complete control over other people's property, other people's money, other people's labor — other people's lives. For too many of us life was no longer free; liberty no longer real; men could no longer follow the pursuit of happiness.

Against economic tyranny such as this, the American citizen could appeal only to the organized power of government. The collapse of 1929 showed up the despotism for what it was. The election of 1932 was the people's mandate to end it. Under that mandate it is being ended.

- These economic royalists complain that we seek to overthrow the institutions of America. What they really complain of is that we seek to take away their power. Our allegiance to American institutions requires the overthrow of this kind of power. In vain they seek to hide behind the flag and the Constitution. In their blindness they forget what the flag and the Constitution stand for. Now, as always, they stand for democracy, not tyranny; for freedom, not subjection; and against a dictatorship by mob rule and the over-privileged alike.

- The brave and clear platform adopted by this convention, to which I heartily subscribe, sets forth that government in a modern civilization has certain inescapable obligations to its citizens, among which are protection of the family and the home, the establishment of a democracy of opportunity, and aid to those overtaken by disaster.

- We do not see faith, hope, and charity as unattainable ideals, but we use them as stout supports of a nation fighting the fight for freedom in a modern civilization.

Faith — in the soundness of democracy in the midst of dictatorships.

Hope — renewed because we know so well the progress we have made.

Charity — in the true spirit of that grand old word. For charity literally translated from the original means love, the love that understands, that does not merely share the wealth of the giver, but in true sympathy and wisdom helps men to help themselves.

- Governments can err, presidents do make mistakes, but the immortal Dante tells us that Divine justice weighs the sins of the cold-blooded and the sins of the warm-hearted on different scales. Better the occasional faults of a government that lives in a spirit of charity than the consistent omissions of a government frozen in the ice of its own indifference.

- There is a mysterious cycle in human events. To some generations much is given. Of other generations much is expected. This generation of Americans has a rendezvous with destiny.

Address at Chautauqua, New York (1936)

edit- Address at Chautauqua, New York (14 August 1936)

- Many who have visited me in Washington in the past few months may have been surprised when I have told them that personally and because of my own daily contacts with all manner of difficult situations I am more concerned and less cheerful about international world conditions than about our immediate domestic prospects.

I say this to you not as a confirmed pessimist but as one who still hopes that envy, hatred and malice among Nations have reached their peak and will be succeeded by a new tide of peace and good-will.

- We are not isolationists except in so far as we seek to isolate ourselves completely from war. Yet we must remember that so long as war exists on earth there will be some danger that even the Nation which most ardently desires peace may be drawn into war.

- I have seen war. I have seen war on land and sea. I have seen blood running from the wounded. I have seen men coughing out their gassed lungs. I have seen the dead in the mud. I have seen cities destroyed. I have seen two hundred limping exhausted men come out of line-the survivors of a regiment of one thousand that went forward forty-eight hours before. I have seen children starving. I have seen the agony of mothers and wives. I hate war.

- I wish I could keep war from all Nations; but that is beyond my power. I can at least make certain that no act of the United States helps to produce or to promote war. I can at least make clear that the conscience of America revolts against war and that any Nation which provokes war forfeits the sympathy of the people of the United States.

- Many causes produce war. There are ancient hatreds, turbulent frontiers, the "legacy of old forgotten, far-off things, and battles long ago." There are new-born fanaticisms. Convictions on the part of certain peoples that they have become the unique depositories of ultimate truth and right.

- A dark old world was devastated by wars between conflicting religions. A dark modern world faces wars between conflicting economic and political fanaticisms in which are intertwined race hatreds.

Address at the Democratic State Convention, Syracuse, New York (1936)

edit- Address at the Democratic State Convention, Syracuse, New York (29 September 1936)

- The task on our part is twofold: First, as simple patriotism requires, to separate the false from the real issues; and, secondly, with facts and without rancor, to clarify the real problems for the American public.

There will be — there are — many false issues. In that respect, this will be no different from other campaigns. Partisans, not willing to face realities, will drag out red herrings as they have always done — to divert attention from the trail of their own weaknesses.

- Desperate in mood, angry at failure, cunning in purpose, individuals and groups are seeking to make Communism an issue in an election where Communism is not a controversy between the two major parties.

Here and now, once and for all, let us bury that red herring, and destroy that false issue. You are familiar with my background; you know my heritage; and you are familiar, especially in the State of New York, with my public service extending back over a quarter of a century. For nearly four years I have been President of the United States. A long record has been written. In that record, both in this State and in the national capital, you will find a simple, clear and consistent adherence not only to the letter, but to the spirit of the American form of government.

- The true conservative seeks to protect the system of private property and free enterprise by correcting such injustices and inequalities as arise from it. The most serious threat to our institutions comes from those who refuse to face the need for change. Liberalism becomes the protection for the far-sighted conservative.

Never has a Nation made greater strides in the safeguarding of democracy than we have made during the past three years. Wise and prudent men — intelligent conservatives — have long known that in a changing world worthy institutions can be conserved only by adjusting them to the changing time. In the words of the great essayist, "The voice of great events is proclaiming to us. Reform if you would preserve." I am that kind of conservative because I am that kind of liberal.- Roosevelt here slightly misquotes Thomas Babington Macaulay, who in a speech on parliamentary reform (2 March 1831) asserted: "The voice of great events is proclaiming to us, Reform, that you may preserve."

- Let me warn you, and let me warn the nation, against the smooth evasion that says: "Of course we believe these things. We believe in social security. We believe in work for the unemployed. We believe in saving homes. Cross our hearts and hope to die! We believe in all these things. But we do not like the way that the present administration is doing them. Just turn them over to us. We will do all of them, we will do more of them, we will do them better and, most important of all, the doing of them will not cost anybody anything!"

Address at Madison Square Garden (1936)

edit- Address at Madison Square Garden, New York City (31 October 1936)

- We had to struggle with the old enemies of peace — business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking, class antagonism, sectionalism, war profiteering. They had begun to consider the Government of the United States as a mere appendage to their own affairs. We know now that Government by organized money is just as dangerous as Government by organized mob. Never before in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me — and I welcome their hatred.

- The very employers and politicians and publishers who talk most loudly of class antagonism and the destruction of the American system now undermine that system by this attempt to coerce the votes of the wage earners of this country. It is the 1936 version of the old threat to close down the factory or the office if a particular candidate does not win. It is an old strategy of tyrants to delude their victims into fighting their battles for them. Every message in a pay envelope, even if it is the truth, is a command to vote according to the will of the employer. But this propaganda is worse — it is deceit.

- No man can occupy the office of President without realizing that he is President of all the people.

Second inaugural address (1937)

edit- Second Inaugural Address (20 January 1937)

- The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.

- We have always known that heedless self-interest was bad morals; we know now that it is bad economics.

Message to Congress on establishing minimum wages and maximum hours (1937)

edit- Message to Congress on Establishing Minimum Wages and Maximum Hours (24 May 1937) in regard to what became the Fair Labor Standards Act.

- A self-supporting and self-respecting democracy can plead no justification for the existence of child labor, no economic reason for chiseling workers' wages or stretching workers' hours.

- Enlightened business is learning that competition ought not to cause bad social consequences which inevitably react upon the profits of business itself. All but the hopelessly reactionary will agree that to conserve our primary resources of man power, government must have some control over maximum hours, minimum wages, the evil of child labor and the exploitation of unorganized labor.

Quarantine Speech (1937)

edit- Quarantine the Aggressor Speech, Chicago, Illinois (5 October 1937)

- The peace-loving nations must make a concerted effort in opposition to those violations of treaties and those ignorings of humane instincts which today are creating a state of international anarchy and instability from which there is no escape through mere isolation or neutrality.

- Those who cherish their freedom and recognize and respect the equal right of their neighbors to be free and live in peace must work together for the triumph of law and moral principles in order that peace, justice, and confidence may prevail in the world. There must be a return to a belief in the pledged word, in the value of a signed treaty. There must be recognition of the fact that national morality is as vital as private morality.

- There is a solidarity and interdependence about the modern world, both technically and morally, which makes it impossible for any nation completely to isolate itself from economic and political upheavals in the rest of the world, especially when such upheavals appear to be spreading and not declining. There can be no stability or peace either within nations or between nations except under laws and moral standards adhered to by all. International anarchy destroys every foundation for peace. It jeopardizes either the immediate or the future security of every nation, large or small. It is, therefore, a matter of vital interest and concern to the people of the United States that the sanctity of international treaties and the maintenance of international morality be restored.

- It is true that the moral consciousness of the world must recognize the importance of removing injustices and well-founded grievances; but at the same time it must be aroused to the cardinal necessity of honoring sanctity of treaties, of respecting the rights and liberties of others, and of putting an end to acts of international aggression.

- It seems to be unfortunately true that the epidemic of world lawlessness is spreading. When an epidemic of physical disease starts to spread, the community approves and joins in a quarantine of the patients in order to protect the health of the community against the spread of the disease.

- No nation which refuses to exercise forbearance and to respect the freedom and rights of others can long remain strong and retain the confidence and respect of other nations. No nation ever loses its dignity or good standing by conciliating its differences and by exercising great patience with, and consideration for, the rights of other nations.

- War is a contagion, whether it be declared or undeclared. It can engulf states and peoples remote from the original scene of hostilities. We are determined to keep out of war, yet we cannot insure ourselves against the disastrous effects of war and the dangers of involvement. We are adopting such measures as will minimize our risk of involvement, but we cannot have complete protection in a world of disorder in which confidence and security have broken down.

- If civilization is to survive, the principles of the Prince of Peace must be restored. Shattered trust between nations must be revived. Most important of all, the will for peace on the part of peace-loving nations must express itself to the end that nations that may be tempted to violate their agreements and the rights of others will desist from such a cause. There must be positive endeavors to preserve peace. America hates war. America hopes for peace. Therefore, America actively engages in the search for peace.

Fireside Chat on Economic Conditions (1938)

edit- F.D.R. On Economic Conditions: 12th Fireside Address, (April 14, 1938)

- Democracy has disappeared in several other great nations — disappeared not because the people of those nations disliked democracy, but because they had grown tired of unemployment and insecurity, of seeing their children hungry while they sat helpless in the face of government confusion, government weakness — weakness through lack of leadership in government. Finally, in desperation, they chose to sacrifice liberty in the hope of getting something to eat. We in America know that our own democratic institutions can be preserved and made to work. But in order to preserve them we need to act together, to meet the problems of the Nation boldly, and to prove that the practical operation of democratic government is equal to the task of protecting the security of the people.

Fireside Chat in the night before signing the Fair Labor Standards Act (1938)

edit- Fireside Chat (24 June 1938), given the night before signing the Fair Labor Standards Act, which instituted the federal minimum wage.

- After many requests on my part the Congress passed a Fair Labor Standards Act, commonly called the Wages and Hours Bill. That Act — applying to products in interstate commerce-ends child labor, sets a floor below wages and a ceiling over hours of labor. Except perhaps for the Social Security Act, it is the most far-reaching, far-sighted program for the benefit of workers ever adopted here or in any other country. Without question it starts us toward a better standard of living and increases purchasing power to buy the products of farm and factory.

- Do not let any calamity-howling executive with an income of $1,000 a day, who has been turning his employees over to the Government relief rolls in order to preserve his company's undistributed reserves, tell you – using his stockholders' money to pay the postage for his personal opinions — tell you that a wage of $11.00 a week is going to have a disastrous effect on all American industry. Fortunately for business as a whole, and therefore for the Nation, that type of executive is a rarity with whom most business executives heartily disagree.

- The Congress has provided a fact-finding Commission to find a path through the jungle of contradictory theories about wise business practices — to find the necessary facts for any intelligent legislation on monopoly, on price-fixing and on the relationship between big business and medium-sized business and little business. Different from a great part of the world, we in America persist in our belief in individual enterprise and in the profit motive; but we realize we must continually seek improved practices to insure the continuance of reasonable profits, together with scientific progress, individual initiative, opportunities for the little fellow, fair prices, decent wages and continuing employment.

- The Congress has understood that under modern conditions government has a continuing responsibility to meet continuing problems, and that Government cannot take a holiday of a year, a month, or even a day just because a few people are tired or frightened by the inescapable pace of this modern world in which we live.

- I am still convinced that the American people, since 1932, continue to insist on two requisites of private enterprise, and the relationship of Government to it. The first is complete honesty at the top in looking after the use of other people's money, and in apportioning and paying individual and corporate taxes according to ability to pay. The second is sincere respect for the need of all at the bottom to get work — and through work to get a really fair share of the good things of life, and a chance to save and rise.

- An election cannot give a country a firm sense of direction if it has two or more national parties which merely have different names but are as alike in their principles and aims as peas in the same pod.

- I certainly would not indicate a preference in a State primary merely because a candidate, otherwise liberal in outlook, had conscientiously differed with me on any single issue. I should be far more concerned about the general attitude of a candidate toward present day problems and his own inward desire to get practical needs attended to in a practical way. We all know that progress may be blocked by outspoken reactionaries and also by those who say "yes" to a progressive objective, but who always find some reason to oppose any specific proposal to gain that objective. I call that type of candidate a "yes, but" fellow.

- And I am concerned about the attitude of a candidate or his sponsors with respect to the rights of American citizens to assemble peaceably and to express publicly their views and opinions on important social and economic issues. There can be no constitutional democracy in any community which denies to the individual his freedom to speak and worship as he wishes. The American people will not be deceived by anyone who attempts to suppress individual liberty under the pretense of patriotism. This being a free country with freedom of expression — especially with freedom of the press — there will be a lot of mean blows struck between now and Election Day. By "blows" I mean misrepresentation, personal attack and appeals to prejudice. It would be a lot better, of course, if campaigns everywhere could be waged with arguments instead of blows.

- In nine cases out of ten the speaker or writer who, seeking to influence public opinion, descends from calm argument to unfair blows hurts himself more than his opponent.

The Chinese have a story on this — a story based on three or four thousand years of civilization: Two Chinese coolies were arguing heatedly in the midst of a crowd. A stranger expressed surprise that no blows were being struck. His Chinese friend replied: "The man who strikes first admits that his ideas have given out."

Address at the dedication of the memorial on the Gettysburg battlefield (1938)

edit- Address at the Dedication of the Memorial on the Gettysburg Battlefield, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania (3 July 1938)

- It seldom helps to wonder how a statesman of one generation would surmount the crisis of another. A statesman deals with concrete difficulties — with things which must be done from day to day. Not often can he frame conscious patterns for the far off future. But the fullness of the stature of Lincoln's nature and the fundamental conflict which events forced upon his Presidency invite us ever to turn to him for help. For the issue which he restated here at Gettysburg seventy five years ago will be the continuing issue before this Nation so long as we cling to the purposes for which the Nation was founded — to preserve under the changing conditions of each generation a people's government for the people's good.

- The task assumes different shapes at different times. Sometimes the threat to popular government comes from political interests, sometimes from economic interests, sometimes we have to beat off all of them together. But the challenge is always the same — whether each generation facing its own circumstances can summon the practical devotion to attain and retain that greatest good for the greatest number which this government of the people was created to ensure.

- Lincoln spoke in solace for all who fought upon this field; and the years have laid their balm upon their wounds. Men who wore the blue and men who wore the gray are here together, a fragment spared by time. They are brought here by the memories of old divided loyalties, but they meet here in united loyalty to a united cause which the unfolding years have made it easier to see. All of them we honor, not asking under which flag they fought then — thankful that they stand together under one flag now. Lincoln was commander-in-chief in this old battle; he wanted above all things to be commander-in-chief of the new peace. He understood that battle there must be; that when a challenge to constituted government is thrown down, the people must in self-defense take it up; that the fight must be fought through to a decision so clear that it is accepted as being beyond recall.

- But Lincoln also understood that after such a decision, a democracy should seek peace through a new unity. For a democracy can keep alive only if the settlement of old difficulties clears the ground and transfers energies to face new responsibilities. Never can it have as much ability and purpose as it needs in that striving; the end of battle does not end the infinity of those needs. That is why Lincoln — commander of a people as well as of an army — asked that his battle end "with malice toward none, with charity for all."

- To the hurt of those who came after him, Lincoln's plea was long denied. A generation passed before the new unity became accepted fact. In later years new needs arose, and with them new tasks, worldwide in their perplexities, their bitterness and their modes of strife. Here in our land we give thanks that, avoiding war, we seek our ends through the peaceful processes of popular government under the Constitution. It is another conflict, a conflict as fundamental as Lincoln's, fought not with glint of steel, but with appeals to reason and justice on a thousand fronts — seeking to save for our common country opportunity and security for citizens in a free society. We are near to winning this battle. In its winning and through the years may we live by the wisdom and the humanity of the heart of Abraham Lincoln.

Address at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. December 5, 1938

edit- In those days, 1913 and 1914, the leadership of the Nation was in the hands of a great President who was seeking to recover for our social system ground that had been lost under his conservative predecessor, and to restore something of the fighting liberal spirit which the Nation had gained under Theodore Roosevelt. It seemed one of our great national tragedies that just when Woodrow Wilson was beginning to accomplish definite improvements in the living standards of America, the World War not only interrupted his course, but laid the foundation for twelve years of retrogression. I say this advisedly because it is not progress, but the reverse, when a nation goes through the madness of the twenties, piling up paper profits, hatching all manner of speculations and coming inevitably to the day when the bubble bursts.

- It is only the unthinking liberals in this world who see nothing but tragedy in the slowing up or temporary stopping of liberal progress.

- It is only the unthinking conservatives who rejoice down in their hearts when a social or economic reform fails to be 100 per cent successful.

- It is only the possessors of "headline" mentality that exaggerate or distort the true objectives of those in this Nation whether they be the president of the University of North Carolina or the President of the United States, who, with Mr. Justice Cardozo, admit the fact of change and seek to guide change into the right channels to the greater glory of God and the greater good of mankind.

- You undergraduates who see me for the first time have read your newspapers and heard on the air that I am, at the very least, an ogre — a consorter with Communists, a destroyer of the rich, a breaker of our ancient traditions. Some of you think of me perhaps as the inventor of the economic royalist, of the wicked utilities, of the money changers of the Temple. You have heard for six years that I was about to plunge the Nation into war; that you and your little brothers would be sent to the bloody fields of battle in Europe; that I was driving the Nation into bankruptcy; and that I breakfasted every morning on a dish of "grilled millionaire.,, (Laughter)

- Actually I am an exceedingly mild mannered person — a practitioner of peace, both domestic and foreign, a believer in the capitalistic system, and for my breakfast a devotee of scrambled eggs. ( Laughter)

- You have read that as a result of the balloting last November, the liberal forces in the United States are on their way to the cemetery — yet I ask you to remember that liberal forces in the United States have often been killed and buried, with the inevitable result that in short order they have come to life again with more strength than they had before.

Address to the Governing Board of the Pan American Union (1939)

edit- Address to the Governing Board of the Pan American Union, (14 April 1939)

- There is no fatality which forces the Old World towards new catastrophe. Men are not prisoners of fate, but only prisoners of their own minds. They have within themselves the power to become free at any moment.

1940s

edit- The Russian armies are killing more Axis personnel and destroying more Axis materiel than all the other 25 nations put together.

- Quoted in WWII: Why Russia remembers the victory, The Herald.

- If the spirit of God is not in us, and if we will not prepare to give all that we have and all that we are to preserve Christian civilization in our land, we shall go to destruction.

- Speech at the Dedication of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, September 2, 1940

- I don't want to see a single war millionaire created in the United States as a result of this world disaster.

- Presidential press conference (21 May 1940), in Complete presidential press conferences of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Volumes 15-16 (Da Capo Press, 1972)

- We guard against the forces of anti-Christian aggression, which may attack us from without, and the forces of ignorance and fear which may corrupt us from within.

- Speech at Madison Square Garden, October 28, 1940

- It seems to me that the dedication of a library is in itself an act of faith.

- Remarks at the Dedication of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library at Hyde Park, New York, United States of America (June 30, 1941). Archived from the original on January 30, 2021.

- To bring together the records of the past and to house them in buildings where they will be preserved for the use of men and women in the future, a Nation must believe in three things. It must believe in the past. It must believe in the future. It must, above all, believe in the capacity of its own people so to learn from the past that they can gain in judgment in creating their own future.

- Remarks at the Dedication of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library at Hyde Park, New York, United States of America (June 30, 1941). Archived from the original on January 30, 2021.

- Among democracies, I think through all the recorded history of the world, the building of permanent institutions like libraries and museums for the use of all the people flourishes. And that is especially true in our own land, because we believe that people ought to work out for themselves, and through their own study, the determination of their best interest rather than accept such so-called information as may be handed out to them by certain types of self-constituted leaders who decide what is best for them.

- Your Government has in its possession another document, made in Germany by Hitler's Government... It is a plan to abolish all existing religions — Catholic, Protestant, Mohammedan, Hindu, Buddhist, and Jewish alike. The property of all churches will be seized by the Reich and its puppets. The cross and all other symbols of religion are to be forbidden. The clergy are to be forever liquidated, silenced under penalty of the concentration camps, where even now so many fearless men are being tortured because they have placed God above Hitler.

- Speech: “Navy and Total Defense Day Address” (Oct. 27, 1941), Roosevelt, D. Franklin, Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States (1941) vol. 10, p. 440

- We defend and we build a way of life, not for America alone, but for all mankind.

- Fireside chat on national defense (May 26, 1940), reported in The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1940 (1941), p. 240

- On this tenth day of June, 1940, the hand that held the dagger has struck it into the back of its neighbor.

- Noting Italy's declaration of war against France on that day, during the commencement address at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville (June 10, 1940); reported in The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1940 (1941), p. 263

- All free peoples are deeply impressed by the courage and steadfastness of the Greek nation.

- Letter to King George of Greece (5 December 1940)

- We must scrupulously guard the civil rights and civil liberties of all our citizens, whatever their background. We must remember that any oppression, any injustice, any hatred, is a wedge designed to attack our civilization.

- Greeting to the American Committee for Protection of Foreign-born (9 January 1940); later inscribed on the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial.

- We must be the great arsenal of Democracy.

- Fireside Chat on National Security, Washington, D.C. (29 December 1940)

- Today the whole world is divided: divided between human slavery and human freedom- between pagan brutality and the Christian ideal. We choose human freedom, which is the Christian ideal.

- Speech on May 27, 1941

- On this day - this American holiday - we are celebrating the rights of free laboring men and women. The preservation of these rights is vitally important now, not only to us who enjoy them - but to the whole future of Christian civilisation.

- Speech on Labor Day, September 1st 1941

- Nazi forces are not seeking mere modifications in colonial maps or in minor European boundaries. They openly seek the destruction of all elective systems of government on every continent-including our own; they seek to establish systems of government based on the regimentation of all human beings by a handful of individual rulers who have seized power by force. These men and their hypnotized followers call this a new order. It is not new. It is not order.

- Address to the Annual Dinner for White House Correspondents' Association, Washington, D.C. (15 March 1941). A similar (but misleading 'quote') is inscribed on the FDR memorial, in Washington D. C., which says "They (who) seek to establish systems of government based on the regimentation of all human beings by a handful of individual rulers... Call this a New Order. It is not new and it is not order".

- If there is anyone who still wonders why this war is being fought, let him look to Norway. If there is anyone who has any delusions that this war could have been averted, let him look to Norway; and if there is anyone who doubts the democratic will to win, again I say, let him look to Norway.

- Speech at the Washington Navy Yard (16 September 1942)

- I may say that I 'got along fine' with Marshal Stalin. He is a man who combines a tremendous, relentless determination with a stalwart good humor. I believe he is truly representative of the heart and soul of Russia; and I believe that we are going to get along very well with him and the Russian people - very well indeed.

- As quoted in History of American Political Thought (1943)

- We have faith that future generations will know that here, in the middle of the twentieth century, there came a time when men of good will found a way to unite, and produce, and fight to destroy the forces of ignorance, and intolerance, and slavery, and war.

- Address to White House Correspondents' Association, Washington, D.C. (12 February 1943)

- World peace is not a party question. [...] The structure of world peace cannot be the work of one man, or one party, or one Nation. It cannot be just an American peace, or a British peace, or a Russian, a French, or a Chinese peace. It cannot be a peace of large Nations- or of small Nations. It must be a peace which rests on the cooperative effort of the whole world. It cannot be a structure of complete perfection at first. But it can be a peace—and it will be a peace—based on the sound and just principles of the Atlantic Charter— on the concept of the dignity of the human being—and on the guarantees of tolerance and freedom of religious worship. [...] We shall have to take the responsibility for world collaboration, or we shall have to bear the responsibility for another world conflict. [...] Peace can endure only so long as humanity really insists upon it, and is willing to work for it—and sacrifice for it.

- Address to Congress on Yalta (1 March 1945)

- I just have a hunch that Stalin is not that kind of man. Harry [Hopkins] says he's not and that he doesn't want anything except security for his own country, and I think that if I give him everything I possibly can and ask nothing from him in return, noblesse oblige, he won't try to annex anything and will work with me for a world of democracy and peace.

- Response to advice from Ambassador William C. Bullitt to pursue a containment policy against the Soviet Union (1943), quoted in his account in Life (23 August 1948)

State of the Union Address — The Four Freedoms (1941)

edit- Eighth State of the Union Address, known as the Four Freedoms Speech (6 January 1941)

- In the future days which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms.

The first is freedom of speech and expression — everywhere in the world.

The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way — everywhere in the world.

The third is freedom from want, which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants — everywhere in the world.

The fourth is freedom from fear, which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor — anywhere in the world.

That is no vision of a distant millennium. It is a definite basis for a kind of world attainable in our own time and generation.

- This nation has placed its destiny in the hands and heads and hearts of its millions of free men and women; and its faith in freedom under the guidance of God. Freedom means the supremacy of human rights everywhere. Our support goes to those who struggle to gain those rights or keep them. Our strength is our unity of purpose.

To that high concept there can be no end save victory.

- As a nation, we may take pride in the fact that we are soft-hearted; but we cannot afford to be soft-headed.

- We must especially beware of that small group of selfish men who would clip the wings of the American Eagle in order to feather their own nests.

- We are committed to the proposition that principles of morality and considerations for our own security will never permit us to acquiesce in a peace dictated by aggressors and sponsored by appeasers. We know that enduring peace cannot be bought at the cost of other people's freedom.

Third inaugural address (1941)

edit- On each national day of inauguration since 1789, the people have renewed their sense of dedication to the United States.

- In Washington's day the task of the people was to create and weld together a nation. In Lincoln's day the task of the people was to preserve that Nation from disruption from within. In this day the task of the people is to save that Nation and its institutions from disruption from without.

- To us there has come a time, in the midst of swift happenings, to pause for a moment and take stock — to recall what our place in history has been, and to rediscover what we are and what we may be. If we do not, we risk the real peril of inaction.

- Lives of nations are determined not by the count of years, but by the lifetime of the human spirit. The life of a man is three-score years and ten: a little more, a little less. The life of a nation is the fullness of the measure of its will to live.

- There are men who doubt this. There are men who believe that democracy, as a form of Government and a frame of life, is limited or measured by a kind of mystical and artificial fate — that, for some unexplained reason, tyranny and slavery have become the surging wave of the future — and that freedom is an ebbing tide. But we Americans know that this is not true.

- Eight years ago, when the life of this Republic seemed frozen by a fatalistic terror, we proved that this is not true. We were in the midst of shock — but we acted. We acted quickly, boldly, decisively.

- For action has been taken within the three-way framework of the Constitution of the United States. The coordinate branches of the Government continue freely to function. The Bill of Rights remains inviolate. The freedom of elections is wholly maintained. Prophets of the downfall of American democracy have seen their dire predictions come to naught.

- Democracy is not dying. We know it because we have seen it revive — and grow. We know it cannot die — because it is built on the unhampered initiative of individual men and women joined together in a common enterprise — an enterprise undertaken and carried through by the free expression of a free majority.

- We know it because democracy alone, of all forms of government, enlists the full force of men's enlightened will.

- We know it because democracy alone has constructed an unlimited civilization capable of infinite progress in the improvement of human life.

- We know it because, if we look below the surface, we sense it still spreading on every continent — for it is the most humane, the most advanced, and in the end the most unconquerable of all forms of human society.

- The democratic aspiration is no mere recent phase in human history. It is human history. It permeated the ancient life of early peoples. It blazed anew in the Middle Ages. It was written in Magna Charta.

- In the Americas its impact has been irresistible. America has been the New World in all tongues, to all peoples, not because this continent was a new-found land, but because all those who came here believed they could create upon this continent a new life — a life that should be new in freedom.

- The hopes of the Republic cannot forever tolerate either undeserved poverty or self-serving wealth.

- We know that we still have far to go; that we must more greatly build the security and the opportunity and the knowledge of every citizen, in the measure justified by the resources and the capacity of the land.

- But it is not enough to achieve these purposes alone. It is not enough to clothe and feed the body of this Nation, and instruct and inform its mind. For there is also the spirit. And of the three, the greatest is the spirit. Without the body and the mind, as all men know, the Nation could not live. But if the spirit of America were killed, even though the Nation's body and mind, constricted in an alien world, lived on, the America we know would have perished.

- The destiny of America was proclaimed in words of prophecy spoken by our first President in his first inaugural in 1789 — words almost directed, it would seem, to this year of 1941: "The preservation of the sacred fire of liberty and the destiny of the republican model of government are justly considered … deeply,... finally, staked on the experiment intrusted to the hands of the American people."

- If we lose that sacred fire — if we let it be smothered with doubt and fear — then we shall reject the destiny which Washington strove so valiantly and so triumphantly to establish. The preservation of the spirit and faith of the Nation does, and will, furnish the highest justification for every sacrifice that we may make in the cause of national defense.

- In the face of great perils never before encountered, our strong purpose is to protect and to perpetuate the integrity of democracy. For this we muster the spirit of America, and the faith of America. We do not retreat. We are not content to stand still. As Americans, we go forward, in the service of our country, by the will of God.

Response to the attack on Pearl Harbor (1941)

edit- Yesterday, December 7, 1941 — a date which will live in infamy — the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.

The United States was at peace with that nation, and, at the solicitation of Japan, was still in conversation with its government and its Emperor looking toward the maintenance of peace in the Pacific.

- It will be recorded that the distance of Hawaii from Japan makes it obvious that the attack was deliberately planned many days or even weeks ago. During the intervening time the Japanese Government has deliberately sought to deceive the United States by false statements and expressions of hope for continued peace.

- As Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy I have directed that all measures be taken for our defense, that always will our whole nation remember the character of the onslaught against us. No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people, in their righteous might, will win through to absolute victory.

- Hostilities exist. There is no blinking at the fact that our people, our territory and our interests are in grave danger. With confidence in our armed forces, with the unbounding determination of our people, we will gain the inevitable triumph, so help us God.

- I ask that the Congress declare that since the unprovoked and dastardly attack by Japan on Sunday, December 7, 1941, a state of war has existed between the United States and the Japanese Empire

State of the Union Address (1943)

edit- State of the Union Address (7 January 1943); Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: F.D. Roosevelt, 1943, Volume 12 (Library Reprints; 1950 edition (2007)

- I cannot tell you when or where the United Nations are going to strike next in Europe. But we are going to strike — and strike hard. I cannot tell you whether we are going to hit them in Norway, or through the Low Countries, or in France, or through Sardinia or Sicily, or through the Balkans, or through Poland — or at several points simultaneously. But I can tell you that no matter where and when we strike by land, we and the British and the Russians will hit them from the air heavily and relentlessly. Day in and day out we shall heap tons upon tons of high explosives on their war factories and utilities and seaports.

Hitler and Mussolini will understand now the enormity of their miscalculations — that the Nazis would always have the advantage of superior air power as they did when they bombed Warsaw, and Rotterdam, and London and Coventry. That superiority has gone — forever.

Yes, we believe that the Nazis and the Fascists have asked for it — and they are going to get it.

State of the Union Address — Second Bill of Rights (1944)

editIt is our duty now to begin to lay the plans and determine the strategy for the winning of a lasting peace and the establishment of an American standard of living higher than ever before known. We cannot be content, no matter how high that general standard of living may be, if some fraction of our people—whether it be one-third or one-fifth or one-tenth—is ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill-housed, and insecure.

This Republic had its beginning, and grew to its present strength, under the protection of certain inalienable political rights—among them the right of free speech, free press, free worship, trial by jury, freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures. They were our rights to life and liberty.

As our nation has grown in size and stature, however—as our industrial economy expanded—these political rights proved inadequate to assure us equality in the pursuit of happiness.

We have come to a clear realization of the fact that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence. Necessitous men are not free men. People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.