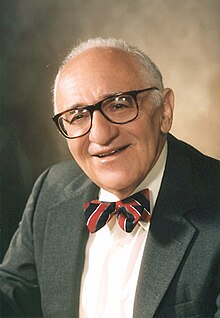

Murray Rothbard

Murray Newton Rothbard (2 March 1926 – 7 January 1995) was an American economist of the Austrian School, an historian of both economic thought and American history, and a political philosopher whose writings and personal influence played a seminal role in the development of modern libertarianism. Rothbard was the founder and leading theoretician of anarcho-capitalism, a staunch advocate of natural law, and a central figure in the twentieth-century American libertarian movement. He was the author of over twenty books on anarchist theory, history, economics, and other subjects.

Quotes

edit- In 1756 Edmund Burke published his first work: Vindication of Natural Society. Curiously enough it has been almost completely ignored in the current Burke revival. This work contrasts sharply with Burke’s other writings, for it is hardly in keeping with the current image of the Father of the New Conservatism. A less conservative work could hardly be imagined; in fact, Burke’s Vindication was perhaps the first modern expression of rationalistic and individualistic anarchism. … "Anarchism" is an extreme term, but no other can adequately describe Burke’s thesis. Again and again, he emphatically denounces any and all government, and not just specific forms of government. … All government, Burke adds, is founded on one "grand error." It was observed that men sometimes commit violence against one another, and that it is therefore necessary to guard against such violence. As a result, men appoint governors among them. But who is to defend the people against the governors? … The anarchism of Burke’s Vindication is negative, rather than positive. It consists of an attack on the State rather than a positive blueprint of the type of society which Burke would regard as ideal. Consequently, both the communist and the individualist wings of anarchism have drawn sustenance from this work.

- "Edmund Burke, Anarchist", first published as "A Note on Burke’s Vindication of Natural Society" in the Journal of the History of Ideas, 19, 1 (January 1958), p. 114.

- Barnes dismissed his own past criticism of the World War II unconditional surrender policy as valid but superficial; for he had learned from General Albert C. Wedemeyer’s book that the murder of Germans and Japanese was the overriding aim of World War II – virtually an Anglo-American scalping party.

- If ‘we are the government,’ then anything a government does to an individual is not only just and untyrannical; it is also ‘voluntary’ on the part of the individual concerned… if the government conscripts a man, or throws him into jail for dissident opinion, then he is ‘doing it to himself’ and therefore nothing untoward has occurred. Under this reasoning, any Jews murdered by the Nazi government were not murdered, instead, they must have ‘committed suicide,’ since they were the government (which was democratically chosen), and therefore anything the government did to them was voluntary on their part… the overwhelming bulk of the people hold this fallacy to a greater or less degree.

- As quoted in “The Anatomy of the State”, Rampart Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2 (summer 1965), reprinted in the Libertarian Alternative, Tibor R. Machan, ed., Chicago: IL, Nelson-Hall (1977) p. 69-70

- It is curious that people tend to regard government as a quasi-divine, selfless, Santa Claus organization. Government was constructed neither for ability nor for the exercise of loving care; government was built for the use of force and for necessarily demagogic appeals for votes. If individuals do not know their own interests in many cases, they are free to turn to private experts for guidance. It is absurd to say that they will be served better by a coercive, demagogic apparatus.

- Power and Market: Government and the Economy, Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006, p. 256. First published in 1970

- All interstate wars intensify aggression – maximize it … some wars are even more unjust than others. In other words, all government wars are unjust, although some governments have less unjust claims…

- As quoted in an interview in Reason magazine (February 1973).

- The natural tendency of the state is inflation.

- I define anarchist society as one where there is no legal possibility for coercive aggression against the person or property of any individual. Anarchists oppose the State because it has its very being in such aggression, namely, the expropriation of private property through taxation, the coercive exclusion of other providers of defense service from its territory, and all of the other depredations and coercions that are built upon these twin foci of invasions of individual rights.

- Briefly, the State is that organization in society which attempts to maintain a monopoly of the use of force and violence in a given territorial area; in particular, it is the only organization in society that obtains its revenue not by voluntary contribution or payment for services rendered but by coercion.

- Murray Rothbard, The Anatomy of the State, Auburn, Alabama, Mises Institute (2009) p.11, first published in 1974 [1]

- The fundamental political question is why do people obey a government. The answer is that they tend to enslave themselves, to let themselves be governed by tyrants. Freedom from servitude comes not from violent action, but from the refusal to serve. Tyrants fall when the people withdraw their support.

- Introduction to Étienne de La Boétie's Politics of Obedience: The Discourse of Voluntary Servitude (1975), p. 39

- It is the state that is robbing all classes, rich and poor, black and white alike; it is the state that is ripping us all off; it is the state that is the common enemy of mankind.

- Murray Rothbard, “The Noblest Cause of All,” Address to the Libertarian Party Convention (1977), Lewrockwell.com [2]

- Rights may be universal, but their enforcement must be local.

- It is no crime to be ignorant of economics, which is, after all, a specialized discipline and one that most people consider to be a 'dismal science.' But it is totally irresponsible to have a loud and vociferous opinion on economic subjects while remaining in this state of ignorance.

- Money is different from all other commodities: other things being equal, more shoes, or more discoveries of oil or copper benefit society, since they help alleviate natural scarcity. But once a commodity is established as a money on the market, no more money at all is needed. Since the only use of money is for exchange and reckoning, more dollars or pounds or marks in circulation cannot confer a social benefit: they will simply dilute the exchange value of every existing dollar or pound or mark. So it is a great boon that gold or silver are scarce and are costly to increase in supply.

But if government manages to establish paper tickets or bank credit as money, as equivalent to gold grams or ounces, then the government, as dominant money-supplier, becomes free to create money costlessly and at will. As a result, this 'inflation' of the money supply destroys the value of the dollar or pound, drives up prices, cripples economic calculation, and hobbles and seriously damages the workings of the market economy.

- Behind the honeyed but patently absurd pleas for equality is a ruthless drive for placing themselves (the elites) at the top of a new hierarchy of power.

- This, by the way, is the welfare state in action: Its a whole bunch of special interest groups screwing consumers and taxpayers, and making them think they're really benefiting.

- from an audio tape of Rothbard's 1986 lecture "Tariffs, Inflation, Anti-Trust and Cartels" [53:47 to 53:55 of 1:47:29], part of the Mises Institute audio lecture series "The American Economy and the End of Laissez-Faire: 1870 to World War II").

- Harold, the young kids out there are not going to be willing to go to the barricades in defense of lowered transaction costs.

- All my life, it seems, I have hated the guts of Max Lerner. Now, make no mistake: there is nothing personal in this rancor. I have never met, nor have I ever had any personal dealings with, Max. No, my absolute loathing for Max Lerner is disinterested, cosmic in its grandeur. It's just that ever since I was a toddler, this ugly homunculus, this pretentious jackass, has been there, towering over the American ideological scene. In the fifty-five years that I have been aware of Max's presence, in all of his many permutations and combinations and seeming twists and turns, he has taken the totally repellent position at every step of the way.

- In short, the early receivers of the new money in this market chain of events gain at the expense of those who receive the money toward the end of the chain, and still worse losers are the people (e.g., those on fixed incomes such as annuities, interest, or pensions) who never receive the new money at all.

- So: if the chronic inflation undergone by Americans, and in almost every other country, is caused by the continuing creation of new money, and if in each country its governmental "Central Bank" (in the United States, the Federal Reserve) is the sole monopoly source and creator of all money, who then is responsible for the blight of inflation? Who except the very institution that is solely empowered to create money, that is, the Fed (and the Bank of England, and the Bank of Italy, and other central banks) itself?

- The Case against the Fed.

- The more consistently Austrian School an economist is, the better a writer he will be.

- As quoted in "An intellectual Autobiography" by Bryan Kaplan, in I Chose Liberty : Autobiographies of Contemporary Libertarians (2010) edited by Walter Block, p. 75.

- The clear and logical thinker will always be an 'extremist', and will therefore always be interesting: his pitafall is to go wildly into error. But on the other hand, while the orthodox 'middle-of-the-road' thinker will never get that far wrong, neither will he ever contribute anything either, aside from being generally deadly dull.

- Review of William Zelermyer's book Invasion of Privacy, published by the Volker Fund (6th October 1960)

- [O]ften, only extremists' make sense, while eclectics and moderates are entangled in contradictions.

- Review of Milton Friedman's book, A program for Monetary Stability, published by the Volker Fund (31th October 1960)

For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto (1973)

edit- If a man has the right to self-ownership, to the control of his life, then in the real world he must also have the right to sustain his life by grappling with and transforming resources; he must be able to own the ground and the resources on which he stands and which he must use. In short, to sustain his "human right."

- The libertarian creed, finally, offers the fulfillment of the best of the American past along with the promise of a far better future. Even more than conservatives... libertarians are squarely in the great classical liberal tradition that built the United States and bestowed on us the American heritage of individual liberty, a peaceful foreign policy, minimal government, and a free-market economy.

What Has Government Done to Our Money? (1980)

edit- The cumulative development of a medium of exchange on the free market — is the only way money can become established. … government is powerless to create money for the economy; it can only be developed by the processes of the free market.

- Money is a commodity … not a useless token only good for exchanging; … It differs from other commodities in being demanded mainly as a medium of exchange.

- It doesn't matter what the supply of money is.

- Inflation may be defined as any increase in the economy's supply of money not consisting of an increase in the stock of the money metal.

- Money … is the nerve center of the economic system. If, therefore, the state is able to gain unquestioned control over the unit of all accounts, the state will then be in a position to dominate the entire economic system, and the whole society.

- Inflation, being a fraudulent invasion of property, could not take place on the free market.

- Freedom can run a monetary system as superbly as it runs the rest of the economy. Contrary to many writers, there is nothing special about money that requires extensive governmental dictation.

The Ethics of Liberty (1982)

edit- The Ethics of Liberty (1982)

- A parent does not have the right to aggress against his children, but also that the parent should not have a legal obligation to feed, clothe, or educate his children, since such obligations would entail positive acts coerced upon the parent and depriving the parent of his rights. The parent therefore may not murder or mutilate his child, and the law properly outlaws a parent from doing so. But the parent should have the legal right not to feed the child, i.e., to allow it to die. The law, therefore, may not properly compel the parent to feed a child or to keep it alive. (Again, whether or not a parent has a moral rather than a legally enforceable obligation to keep his child alive is a completely separate question.) This rule allows us to solve such vexing questions as: should a parent have the right to allow a deformed baby to die (e.g., by not feeding it)? The answer is of course yes, following a fortiori from the larger right to allow any baby, whether deformed or not, to die. (Though, as we shall see below, in a libertarian society the existence of a free baby market will bring such "neglect" down to a minimum.)

- Children and rights, p. 100

An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought (1995)

edit- The problem is that he originated nothing that was true, and that whatever he originated was wrong.

- On Adam Smith.

- John Stuart was the quintessence of soft rather than hardcore, a woolly minded man of mush in striking contrast to his steel-edged father.

- Shameless sponging on friends and relatives … Marx affected a hatred and contempt for the very material resource he was too anxious to cadge and use so recklessly. Marx created an entire philosophy around his own corrupt attitudes toward money.

- Auburn, Alabama. Ludwig von Mises Institute

- One gratifying aspect of our rise to some prominence is that, for the first time in my memory, we, "our side," had captured a crucial word from the enemy. Other words, such as "liberal," had been originally identified with laissez-faire libertarians, but had been captured by left-wing statists, forcing us in the 1940s to call ourselves father feebly "true" or "classical" liberals. "Libertarians"’, in contrast, had long been simply a polite word for left-wing anarchists, that is for anti-private property anarchists, either of the communist or syndicalist variety. But now we had taken it over, and more properly from the view of etymology; since we were proponents of individual liberty and therefore of the individual's right to his property. [3], p. 83

Quotes about Rothbard

edit- According to Rothbard, a child becomes an adult not when he reaches some arbitrary age limit, but rather when he does something to establish his ownership and control over his own person: namely, when he leaves home, and becomes able to support himself. This criteria, and only this criteria, is free of all the objections to arbitrary age limits. Moreover, not only is it consistent with the libertarian homesteading theory, it is but an application of it. For by leaving home and becoming his own means of support, the ex-child becomes an initiator, as the homesteader, and owes his improved state to his own actions.

- Walter Block (1976, 1991, 2008), Defending the Undefendable, Auburn, Alabama: Mises Institute, p. 245

- Let me take the liberty of being uncharitable but truthful.

Rothbard had a problem. He thought he was a great economist, but practically nobody within the profession agreed and most of them had never heard of him.

Rothbard had a solution. He was ignored because he held extreme pro-market views, which were ideologically unpopular in the academy.

Rothbard had a problem. Milton Friedman held extreme pro-market views--not as extreme as Rothbard's, but far enough from academic orthodoxy so that the same effect should have existed. But Milton Friedman not only wasn't ignored, he was viewed within the profession as a leading figure--despite his unpopular political views.

Rothbard had a solution--to persuade himself and his followers that Milton Friedman was really one of them instead of one of us, hence his acceptance by the profession didn't contradict Rothbard's view of the reason for Rothbard's non-acceptance.Maintaining that claim was difficult--at one point I remember being told by a Rothbard supporter, explaining why he was not going to publish a letter of mine in his journal that contained quotes from my father inconsistent with Rothbard's account of my father's views, that if Rothbard and Friedman disagreed about what Friedman's views were, Rothbard was right.

- David Friedman, Comment on "Austrian Fantasy" (July 26, 2011)

- It may come as a surprise to learn that for Rothbard the New Left's most "crucial contribution to both ends and means…is its concept of 'participatory democracy.'" … This may seem less surprising once one realizes that for Rothbard the free market is the fullest realization of participatory democracy. … The political appeal of participatory democracy for Rothbard was its requirement of decentralization, and its rejection of a layer of political "representatives" above the people. But Rothbard also found the idea appealing outside the narrowly political sphere. He wrote: "Participatory democracy is at the same time…a theory of politics and a theory of organization, an approach to political affairs and to the way New Left organizations (or any organizations, for that matter) should function." And he praised "fascinating experiments in which workers are transformed into independent and equal entrepreneurs." Traditional "socialist" goals such as workers' control of industry, then, were apparently not anathema to Rothbard.

Indeed, he would later argue that any nominally private institution that gets more than 50% of its revenue from the government, or is heavily complicit in government crimes, or both, should be considered a government entity; since government ownership is illegitimate, the proper owners of such institutions are "the 'homesteaders', those who have already been using and therefore 'mixing their labor' with the facilities." This entails inter alia "student and/or faculty ownership of the universities." As for the "myriad of corporations which are integral parts of the military-industrial complex," one solution, Rothbard says, is to "turn over ownership to the homesteading workers in the particular plants." He also supported third-world land reforms considered socialistic by many conservatives, on the grounds that existing land tenure represented "continuing aggression by titleholders of land against peasants engaged in transforming the soil."

- Roderick T. Long, "Rothbard's 'Left and Right': Forty Years Later," Rothbard Memorial Lecture, Austrian Scholars Conference (2006).

- For Rothbard, it was precisely capitalism that was the one and only savior of mankind. Whereas Buchanan was a strict constitutionalist and a strong patriot, Rothbard was opposed to government itself—and not just the American government, but all government. According to Rothbard’s anarcho-capitalism, all state functions could be served cheaper, better, and more effectively by the free market. This included the police and even national defense.

- Michael Malice, The New Right: A Journey into the Fringe of American Politics (2019)

- For Rothbard, “no government interference with exchanges can ever increase social utility,” and “[w]e are led inexorably, then, to the conclusion that the processes of the free market always lead to a gain in social utility.” Therefore, “capitalism is the fullest expression of anarchism, and anarchism is the fullest expression of capitalism. Not only are they compatible, but you can’t really have one without the other.” For Rothbardians—as opposed to their archenemies the neocons—the worst of all government activity is war: “It is in war that the State really comes into its own: swelling in power, in number, in pride, in absolute dominion over the economy and the society.” There is no difference between a Lois Lerner and a beat cop. They are both enforcers of the state, albeit in different clothing.

- Michael Malice, The New Right: A Journey into the Fringe of American Politics (2019)

- For the evangelical left, equality and fairness are universally shared goals. Rothbard’s response was a book titled Egalitarianism as a Revolt Against Nature. The idea that freedom and democracy are not only compatible but downright synonymous is taken for granted in contemporary American culture, but here Rothbard disagrees as well. The popular conception of democracy is one in which every voter envisions their ideal society and then votes us in that direction. In the anarchist perspective, this is akin to everyone imagining themselves as a totalitarian dictator and then selecting the politician who will best implement their plan into reality. Rothbard thought of the vote in a different way. By regarding all state action as illegitimate, he viewed the two political parties as literal rival gangs whose power needed to be curtailed as much as possible and hopefully destroyed altogether. He regarded the air of prestige around Congress as akin to a Mafia don’s three-piece suit, a pretense of civility masking the murderous thug within. Accordingly, the New Right still regards vulgarity toward and disrespect for the elites as important mechanisms for revealing their true inner evil. Let them drop their masks and expose themselves as the moral abominations that they really are.

- Michael Malice, The New Right: A Journey into the Fringe of American Politics (2019)

- Finding no room for intellectual discussion in Rand’s sphere (and years later satirizing her in his embarrassingly juvenile and unpublished play Mozart Was a Red), Rothbard searched for other alliances. So while Buchanan was joining with Nixon, Rothbard was singing the praises of Tricky Dick’s archenemies: the New Left. Sometimes it was hard to tell if the anarchist Rothbard was simply looking for people to take him seriously, and at other times it was hard to tell how they could. For Rothbard, the way to freedom was to destroy the only thing that ever stood in its way: government. He praised the Black Power movement at first, seeing it as a useful opponent to the state (though spending little time writing about race per se, being an ultra-individualist). In 1967 Rothbard wrote that Che Guevara was “an heroic figure for our time” and “the living embodiment of the principle of Revolution.” In other words, my enemy’s enemy is my friend—a principle that the New Right struggles with to this day.

- Michael Malice, The New Right: A Journey into the Fringe of American Politics (2019)

- Noam Chomsky describes Murray Rothbard's vision of a libertarian society as "so full of hate that no human being would want to live in it." (I will not attempt to dissect this insane remark here except to note how the "anti-authoritarian" Chomsky purports to speak for all human beings.)

- James Ostrowski (06 Jan 2003), Chomsky's Economics, Mises Daily

- Murray Rothbard said, more than once, that there was nothing wrong about a person not fully understanding economics; but that those ignorant of economic principles ought not to be proposing governmental policies to govern economic activity.

- Butler Shaefer (2012). The Wizards of Ozymandias; Reflections on the Decline and Fall, Auburn, Alabama: Mises Institute, p. 107

- It is my contention that Rothbardian anarcho-capitalism is misnamed because it is actually a variety of socialism, in that it offers an alternative understanding of existing capitalism (or any other variety of statism) as systematic theft from the lower classes and envisions a more just society without that oppression. Rather than depending upon the the labor theory of value to understand this systematic theft, Rothbardian market anarchism utilizes natural law theory and Lockean principles of property and self-ownership taken to their logical extreme as an alternative framework for understanding and combating oppression. ... Murray Rothbard was a visionary socialist ... Because the market anarchist society would be one in which the matter of systematic theft has been addressed and rectified, market anarchism ... is best understood a new variety of socialism—a stigmergic socialism. Stigmergy is a fancy word for systems in which a natural order emerges from the individual choices made by the autonomous components of a collective within the sphere of their own self-sovereignty. To the extent coercion skews markets by distorting the decisions of those autonomous components (individual people), it ought to be seen that a truly free market (a completely stigmergic economic system) necessarily implies anarchy, and that any authentic collectivism is necessarily delineated in its bounds by the the natural rights of the individuals composing the collective.

- Brad Spangler, "Market anarchism as stigmergic socialism," BradSpangler.com (15 September 2006).

See also

editExternal links

edit- Murray Rothbard at Mises Wiki

- Murray N. Rothbard by David Gordon

- Ludwig Von Mises YouTube page including several Rothbard videos

- Murray N. Rothbard Library and Resources

- Murray N. Rothbard Media Archive at Mises.org

- BlackCrayon.com: People: Murray Rothbard

- Chronological Bibliography of Murray Rothbard

- The Complete Archives of The Libertarian Forum

- Sociology of the Ayn Rand Cult

- "It Usually Ends With Ed Crane"

- A 1972 New Banner interview with Murray Rothbard

- A 1990 interview with Murray Rothbard

- Why Hans-Hermann Hoppe considers Rothbard the key Austro-libertarian intellectual

- Remembering Rothbard: Antiwar Archive

- Murray Rothbard Institute

- "Left and Right: The Prospects for Liberty", in "Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought" (Spring 1965)

- "Newt Gingrich is No Libertarian", Washington Post (30 December 1994)p. A17; Rothbard's last newspaper column, before his death

- "The Origins of the Federal Reserve", The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics vol. 2, no. 3 (Fall 1999): 3 – 51