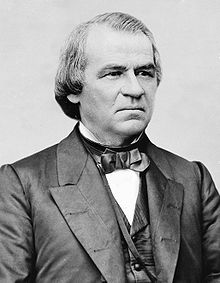

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (29 December 1808 – 31 July 1875) was the seventeenth president of the United States (1865–1869), succeeding to the presidency upon the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Democrat from the Southern states but had supported the Union in the American Civil War and had been nominated as the running mate in Abraham Lincoln's Republican campaign. He presided over the Reconstruction of the United States following the American Civil War and was the first president to be impeached, although he was subsequently acquitted by a single vote in the Senate. As President, he resisted efforts from the Republican Congress to remove white-supremacist supporters of the former Confederacy from state governments and to extend franchise and civil rights to African Americans. For this, historians usually rank him as one of the worst Presidents in U.S. history.

Quotes

- Whenever you hear a man prating about the Constitution, spot him as a traitor.

- Remark made by Johnson as military Governor of Tennessee, as quoted in A Review of the Political Conflict in America (1876) by Alexander Harris, A Review of the Political Conflict in America, p. 430.

- There are no good laws but such as repeal other laws.

- Statement (1835), as quoted in Andrew Johnson, Plebeian and Patriot (1928) by Robert Watson Winston.

- There are some who lack confidence in the integrity and capacity of the people to govern themselves. To all who entertain such fears I will most respectfully say that I entertain none... If a man is not capable, and is not to be trusted with the government of himself, is he to be trusted with the government of others... Who, then, will govern? The answer must be, Man — for we have no angels in the shape of men, as yet, who are willing to take charge of our political affairs.

- Statement (1853) as quoted in Andrew Johnson, Plebeian and Patriot (1928) by Robert Watson Winston.

- No, gentlemen, if I am to be shot at, I want no man to be in the way of the bullet.

- As military governor of Tennessee, asserting that he would walk alone, to friends who offered to escort him to the statehouse, after postings of a placard saying he should be "shot on sight." (c.1862); as quoted in Andrew Johnson, President of the United States: His Life and Speeches (1866) by Lillian Foster.

- Mr. Jefferson meant the white race.

- Regarding the statement in the Declaration of Independence that "all men are created equal."

- "Speech on Harper's Ferry Incident", 12 December 1859; as printed in The papers of Andrew Johnson, Vol. 3: 1858-1860 (1972), ed. LeRoy P. Graf and Ralph W. Haskins, p. 320.

- I have lived among Negroes, all my life, and I am for this Government with slavery under the Constitution as it is. I am for the Government of my fathers with Negroes, I am for it without Negroes. Before I would see this Government destroyed, I would send every negro back to Africa, disintegrated and blotted out of space.

- Speech in Indianapolis, Indiana (26 February 1863).

- Colored men of Tennessee, humble and unworthy as I am, if no better shall be found I will indeed be your Moses and lead you through the Red Sea of war and bondage to a fairer future of liberty and peace. I speak now as one who feels the world his country and all who love equal rights his friends.

- As quoted in "The Good Fight" (1865), by George William Curtis.

- I am a-goin' for to tell you here to-day; yes, I'm a-goin for to tell you all, that I'm a plebian! I glory in it; I am a plebian! The people — yes, the people of the United States have made me what I am; and I am a-goin' for to tell you here to-day — yes, to-day, in this place — that the people are everything.

- First address as Vice-President, widely reported as having been delivered while he was inebriated. (5 March 1865).

- This is your country as well as anybody else's country. This country is founded upon the principle of equality. He that is meritorious and virtuous, intellectual and well informed, must stand highest, without regard to color.

- To Union soldiers (1865), as quoted in Andrew Johnson: A Profile (1969), "Johnson and the Negro", by Lawanda Cox and John H. Cox; edited by Eric L. McKitrick, Hill & Wang, New York pp. 141.

- If you could extend the elective franchise to all persons of color who can read the Constitution of the United States in English and write their names and to all persons of color who own real estate valued at not less than two hundred and fifty dollars and pay taxes thereon, and would completely disarm the adversary. This you can do with perfect safety. And as a consequence, the radicals, who are wild upon negro franchise, will be completely foiled in their attempts to keep the Southern States from renewing their relations to the Union.

- Letter to William L. Sharkey, governor of Mississippi (June 1865).

- Notwithstanding a mendacious press; notwithstanding a subsidized gang of hirelings who have not ceased to traduce me, I have discharged all my official duties and fulfilled my pledges. And I say here tonight that if my predecessor had lived, the vials of wrath would have poured out upon him.

- Speech in Cleveland, Ohio (3 September 1866).

- Those damned sons of bitches thought they had me in a trap! I know that damned Douglass; he's just like any nigger, and he would sooner cut a white man's throat than not.

- As quoted in Andrew Johnson: A Profile (1969), "Johnson and the Negro", by Lawanda Cox and John H. Cox; edited by Eric L. McKitrick, Hill & Wang, New York pp. 152-153.

- I have had a son killed, a son-in-law die during the last battle of Nashville, another son has thrown himself away, a second son-in-law is in no better condition, I think I have had sorrow enough without having my bank account examined by a Committee of Congress.

- Letter to his friend Colonel William G. Moore, complaining of Congressional investigations.... (1 May 1867).

- Legislation can neither be wise nor just which seeks the welfare of a single interest at the expense and to the injury of many and varied interests at least equally important and equally deserving the considerations of Congress.

- Veto message to the House of Representatives (22 February 1869).

- The goal to strive for is a poor government but a rich people.

- As quoted in Andrew Johnson, Plebeian and Patriot (1928) by Robert Watson Winston

- Your President is now the Tribune of the people, and, thank God, I am, and intend to assert the power which the people have placed in me... Tyranny and despotism can be exercised by many, more rigorously, more vigorously, and more severely, than by one.

- As quoted in Presidential Government in the United States: The Unwritten Constitution (1947) by Caleb Perry Patterson.

- If I should happen to die among the damn spirits that infest Greeneville, my last request before death would be for some friend I would bequeath the last dollar to some Negro to pay -- to take my dirty stinking carcass after death out on some mountain peak, and there leave it to be devoured by the vultures and wolves or make a fire sufficiently large to consume the smallest particle that it might pass off and smoke and ride upon the wind in triumph over the God-forsaken and hell-deserving, money-loving, hypocritical, backbiting, Sunday-praying scoundrels of the town of Greeneville.

- U.S. Rep. Andrew Johnson, 1847. As quoted from The Washington Post Presidential Podcast Episode Transcript "Andrew Johnson Stitching up a torn country".[1] Johnson would die of a stroke during 1875 while visiting his daughters at the riverside home of his daughter Mary, some 45 miles away, immediately upstream of Brumit Island and northeast of Elizabethton, Tennessee.[2][3][4][5]

- "This is a country for white men, and, by G—d, as long as I am president it shall be a government for white men." Johnson, quoted in The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation by Brenda Wineapple (p. xviii)

First Presidential address (1865)

- I must be permitted to say that I have been almost overwhelmed by the announcement of the sad event which has so recently occurred. I feel incompetent to perform duties so important and responsible as those which have been so unexpectedly thrown upon me.

- The only assurance that I can now give of the future is reference to the past. The course which I have taken in the past in connection with this rebellion must be regarded as a guaranty of the future. My past public life, which has been long and laborious, has been founded, as I in good conscience believe, upon a great principle of right, which lies at the basis of all things. The best energies of my life have been spent in endeavoring to establish and perpetuate the principles of free government, and I believe that the Government in passing through its present perils will settle down upon principles consonant with popular rights more permanent and enduring than heretofore. I must be permitted to say, if I understand the feelings of my own heart, that I have long labored to ameliorate and elevate the condition of the great mass of the American people. Toil and an honest advocacy of the great principles of free government have been my lot. Duties have been mine; consequences are God's. This has been the foundation of my political creed, and I feel that in the end the Government will triumph and that these great principles will be permanently established.

First State of the Union Address (1865)

- "The sovereignty of the States" is the language of the Confederacy, and not the language of the Constitution. The latter contains the emphatic words — This Constitution and the laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof, and all treaties made or which shall be made under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land, and the judges in every State shall be bound thereby, anything in the constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding.

- Certainly the Government of the United States is a limited government, and so is every State government a limited government. With us this idea of limitation spreads through every form of administration — general, State, and municipal — and rests on the great distinguishing principle of the recognition of the rights of man. The ancient republics absorbed the individual in the state — prescribed his religion and controlled his activity. The American system rests on the assertion of the equal right of every man to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, to freedom of conscience, to the culture and exercise of all his faculties. As a consequence the State government is limited — as to the General Government in the interest of union, as to the individual citizen in the interest of freedom.

- Our Government springs from and was made for the people — not the people for the Government. To them it owes allegiance; from them it must derive its courage, strength, and wisdom. But while the Government is thus bound to defer to the people, from whom it derives its existence, it should, from the very consideration of its origin, be strong in its power of resistance to the establishment of inequalities. Monopolies, perpetuities, and class legislation are contrary to the genius of free government, and ought not to be allowed. Here there is no room for favored classes or monopolies; the principle of our Government is that of equal laws and freedom of industry. Wherever monopoly attains a foothold, it is sure to be a source of danger, discord, and trouble. We shall but fulfill our duties as legislators by according "equal and exact justice to all men," special privileges to none.

- The life of a republic lies certainly in the energy, virtue, and intelligence of its citizens; but it is equally true that a good revenue system is the life of an organized government. I meet you at a time when the nation has voluntarily burdened itself with a debt unprecedented in our annals. Vast as is its amount, it fades away into nothing when compared with the countless blessings that will be conferred upon our country and upon man by the preservation of the nation's life. Now, on the first occasion of the meeting of Congress since the return of peace, it is of the utmost importance to inaugurate a just policy, which shall at once be put in motion, and which shall commend itself to those who come after us for its continuance. We must aim at nothing less than the complete effacement of the financial evils that necessarily followed a state of civil war.

- I hold it the duty of the Executive to insist upon frugality in the expenditures, and a sparing economy is itself a great national resource.

Fourth State of the Union Address (1868)

- It may be safely assumed as an axiom in the government of states that the greatest wrongs inflicted upon a people are caused by unjust and arbitrary legislation, or by the unrelenting decrees of despotic rulers, and that the timely revocation of injurious and oppressive measures is the greatest good that can be conferred upon a nation. The legislator or ruler who has the wisdom and magnanimity to retrace his steps when convinced of error will sooner or later be rewarded with the respect and gratitude of an intelligent and patriotic people.

Our own history, although embracing a period less than a century, affords abundant proof that most, if not all, of our domestic troubles are directly traceable to violations of the organic law and excessive legislation.

- The attempt to place the white population under the domination of persons of color in the South has impaired, if not destroyed, the kindly relations that had previously existed between them: and mutual distrust has engendered a feeling of animosity which leading in some instances to collision and bloodshed, has prevented that cooperation between the two races so essential to the success of industrial enterprise in the Southern States.

Misattributed

- It's a damn poor mind that can only think of one way to spell a word.

- More commonly misattributed to Andrew Jackson, the originator of this line is actually unknown.

Quotes about Johnson

- Johnson stood at his desk. Said "No," had a thousand such applications every day; more papers than he could read. I told him he was mistaken. That he never had such an application in his life. You recognize, I said, Mr. Johnson, that Mrs. Stanton and that myself, for two years, have boldly told the Republican party they must give ballots to women as well as negroes, and by means of The Revolution we are bound to drive the party to logical conclusions, or break it into a thousand pieces as was the old Whig party, unless we get our rights. That brought him to his pocket book, and he signed his name Andrew Johnson, with a bold hand, as much to say, anything to get rid of this woman and break the radical party.

- The Revolution article in Failure Is Impossible: Susan B. Anthony in Her Own Words edited by Lynn Sherr (1995)

- Andrew Johnson had been suspected by many people of being concerned in the plans of Booth against the life of Lincoln or at least cognizant of them. A committee of which I was the head, felt it their duty to make a secret investigation of that matter, and we did our duty in that regard most thoroughly. Speaking for myself I think I ought to say that there was no reliable evidence at all to convince a prudent and responsible man that there was any ground for the suspicions entertained against Johnson.

- Benjamin Franklin Butler, Autobiography and Personal Reminiscences of Major-General Benjamin F. Butler (1892).

- The inauguration went off very well except that the Vice President Elect was too drunk to perform his duties and disgraced himself and the Senate by making a drunken foolish speech. I was never so mortified in my life, had I been able to find a hole I would have dropped through it out of sight.

- Senator Zachariah T. Chandler in a letter to his wife, quoted in the US Senate Biography

- I know how subtle, elusive, apparently ineradicable, is the spirit of caste. But I remember that the English lords six centuries ago tore out the teeth of the Jew Isaac of York in the dungeon under the castle; and today he lives proudly in the castle, and the same lords come respectfully to his daughter's marriage, while the most brilliant Tory in the British Parliament proposes her health, and the Lord Chief Justice of England leads the hip-hip-hurrah at the wedding breakfast. Caste is very strong, but I remember that five years ago there were good men among us who said. If white hands can't win this fight let it be lost. I have seen the same men agreeing that black hands had even more at stake in it than we, giving them muskets, bidding them Godspeed in the Good Fight, and welcoming them with honor as they returned. Caste is very strong, but I remember that six years ago there was a Tennessee slave-holder, born in North Carolina, who had always acted with the slave interest, and was then earnestly endeavoring to elect John C. Breckenridge President of the United States. We have all seen that same man four years afterwards, while Tennessee quivered with civil war, standing beneath the autumn stars and saying, 'Colored men of Tennessee, humble and unworthy as I am, if no better shall be found I will indeed be your Moses and lead you through the Red Sea of war and bondage to a fairer future of liberty and peace. I speak now as one who feels the world his country and all who love equal rights his friends'. So said Andrew Johnson, God and his country listening. God and his country watching, Andrew Johnson will keep his word.

- George William Curtis, as quoted in "The Good Fight" (1865).

- On this inauguration day, while waiting for the opening of the ceremonies, I made a discovery in regard to the vice president — Andrew Johnson. There are moments in the lives of most men, when the doors of their souls are open, and unconsciously to themselves, their true characters may be read by the observant eye. It was at such an instant I caught a glimpse of the real nature of this man, which all subsequent developments proved true. I was standing in the crowd by the side of Mrs. Thomas J. Dorsey, when Mr. Lincoln touched Mr. Johnson, and pointed me out to him. The first expression which came to his face, and which I think was the true index of his heart, was one of bitter contempt and aversion. Seeing that I observed him, he tried to assume a more friendly appearance; but it was too late; it was useless to close the door when all within had been seen. His first glance was the frown of the man, the second was the bland and sickly smile of the demagogue. I turned to Mrs. Dorsey and said, 'Whatever Andrew Johnson may be, he certainly is no friend of our race.

- Frederick Douglass, as quoted in Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881), p. 355.

- The day after I was born, Andrew Johnson was impeached. He deserved punishment as a traitor to the poor Southern whites and poorer freedmen. Yet during his life, no one denied him the right to defend himself.

- The Autobiography of W.E.B. Du Bois: A Soliloquy on Viewing My Life from the Last Decade of Its First Century (1968)

- This traditional view of Reconstruction has long since been abandoned by historians, although it retains a remarkable hold on popular understanding of the era. Today historians emphatically reject the racist underpinnings of the old interpretation, viewing the Reconstruction as a noble if flawed experiment, the first attempt to introduce a genuine inter-racial democracy in the United States. The tragedy was not that Reconstruction was attempted, but that it failed, leaving the problem of racial justice to future generations. In the modern view, blacks were active agents in shaping the era’s history, not simply the victims of manipulation by others. Andrew Johnson was a stubborn, racist politician, whose policies alienated not only Radicals, who never controlled Congress, but the vast majority of Republicans.

- Eric Foner, as quoted in "If Lincoln Hadn’t Died" (2009), American Heritage.

- Andrew Johnson lacked Lincoln's qualities of greatness. While Lincoln had been open-minded, willing to listen to criticism, attuned to the currents of northern public opinion, and able to get along with all elements of his party, Johnson was stubborn, deeply racist, and insensitive to the opinions of others. If anyone was responsible for the wreck of his presidency, it was Johnson himself. First, by establishing new governments in the South in which blacks had no voice whatsoever, and then refusing, when these governments sought to reduce freedpeople to a situation akin to slavery through the Black Codes, to heed the rising tide of northern concern. As congressional opposition mounted, Johnson refused to budge. As a result, Congress swept aside Johnson's Reconstruction plan, enacting a series of measures pivotal in the rightful enlargement of American citizenship and freedom: the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which accorded blacks equality before the law; the Fourteenth Amendment, which put the idea of equality unbounded by race into the Constitution; and the Reconstruction Acts of 1867 and 1868, which mandated the establishment of new governments in the South, enabling black men to vote for the first time in U.S. history. Despite the Constitution's injunction that the president enforce the laws, Johnson did everything in his power to obstruct the implementation of these measures. In 1868, fed up with his intransigence and incompetence, the House impeached Johnson; after a trial in the Senate, he came within one vote of conviction.

- Eric Foner, as quoted in "If Lincoln Hadn’t Died" (2009), American Heritage.

- A man unable to rise to the demands of one of the most challenging moments in our nation's history.

- Eric Foner, as quoted in "If Lincoln Hadn’t Died" (2009), American Heritage.

- Congress incorporated birthright citizenship and legal equality into the Constitution via the 14th Amendment. In recent decades, the courts have used this amendment to expand the legal rights of numerous groups, most recently, gay men and women. As the Republican editor George William Curtis wrote, the Fourteenth Amendment changed a Constitution 'for white men' to one 'for mankind'. It also marked a significant change in the federal balance of power, empowering the national government to protect the rights of citizens against violations by the states. In 1867 Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts, again over Johnson’s veto. These set in motion the establishment of new governments in the South, empowered Southern black men to vote and temporarily barred several thousand leading Confederates from the ballot. Soon after, the 15th Amendment extended black male suffrage to the entire nation. The Reconstruction Acts inaugurated the period of Radical Reconstruction, when a politically mobilized black community, with its white allies, brought the Republican Party to power throughout the South. For the first time, African-Americans voted in large numbers and held public office at every level of government. It was a remarkable, unprecedented effort to build an interracial democracy on the ashes of slavery. Most offices remained in the hands of white Republicans. But the advent of African-Americans in positions of political power aroused bitter hostility from Reconstruction’s opponents.

- Eric Foner, as quoted in "Why Reconstruction Matters" (28 March 2015), by E. Foner, The New York Times, New York.

- Andrew Johnson wasn't a drunkard, he was just a bigot.

- Drew Gibson, "Andrew Johnson Wasn’t a Drunkard…He Was Just a Bigot" (12 February 2014), Virally Suppressed – Muckraking For The Modern World.

- From his quick and largely consequence free reinstatement of former Confederate leaders and endorsement of discriminatory Black Codes in many Southern states, to his vetoing of legislation that proposed civil rights increases and an extension for the Freedman’s Bureau, the old Tennessee War Democrat played the part of the white supremacist savior, effectively killing off any hope that the civil rights of blacks in this country would go beyond mere emancipation in the near future. The slaves had been nominally given their freedom, but Johnson was determined that they shouldn’t be given anything else. Under his watch, the rights and opportunities available to white men would not be extended to any other race and the ascendency of a new American hatred would begin. During his Third Address to Congress, Johnson arguably expounded more overt racially-charged ignorance than any President before or since, essentially outlining what would be the go-to talking points of the Post-Civil War and Jim Crow South for the next 100 years.

- Drew Gibson, "Andrew Johnson Wasn’t a Drunkard…He Was Just a Bigot" (12 February 2014), Virally Suppressed – Muckraking For The Modern World.

- In the span of three years, our country went from a President who urged his fellow Americans to have malice towards none and charity towards all to a President who demonizes one section of the population for the benefit of another and un-ironically warns of a future in which blacks treat whites with the same lack of compassion and respect that whites had always treated blacks. In Andrew Johnson’s words you can hear the contempt and revulsion for his fellow man burbling out in a sea of incoherent hatred. You can see his words spurring on the basest nature of the white southern plebians from which he sprang, settling in them a vicious enmity towards their black brothers and sisters that would cause them to ignore the grave injustices being perpetrated against them by their patrician white fellows. Most of all, you can feel that scar tissue that was built up after Gettysburg and Appomatox and Shiloh begin to slowly crack open, exposing those tender wounds of ours to infection and disease and rot. There would be no healing here.

- Drew Gibson, "Andrew Johnson Wasn’t a Drunkard…He Was Just a Bigot" (12 February 2014), Virally Suppressed – Muckraking For The Modern World.

- This Johnson is a queer man.

- Abraham Lincoln, in a remark to his friend Shelby M. Cullom, after Johnson inquired whether his presence was required at the inauguration, as quoted in A Reporter's Lincoln by Walter B. Stevens, edited by Michael Burlingame

- I have known Andy for many years... he made a bad slip the other day, but you need not be scared. Andy ain't a drunkard.

- Abraham Lincoln, on Johnson's infamous speech on the day of his inauguration as Vice-President, as quoted in Hannibal Hamlin: Lincoln's First Vice President (1969) by H. Draper Hunt.

- It has been a severe lesson for Andy, but I do not think he will do it again.

- Abraham Lincoln, as quoted by Senate aide John Wien Forney, with whom Johnson had been drinking the night before his swearing in as Vice-President, in Anecdotes of Public Men (1873) by John W. Forney.

- It was believed by many at the time that some of the [moderate] Republican Senators that voted for acquittal [of Andrew Johnson] did so chiefly on account of their antipathy to the man who would succeed to the presidency in the event of the conviction of the [sitting] president. This man was Senator Benjamin Wade, of Ohio, President pro tempore of the Senate who as the law then stood, would have succeeded to the presidency in the event of a vacancy in the office from any cause. Senator Wade was an able man … He was a strong party man. He had no patience with those who claimed to be [Radical] Republicans and yet refused to abide by the decision of the majority of the party organization [as did Grimes, Johnson, Lincoln, Pratt, and Trumbull] … the sort of active and aggressive man that would be likely to make for himself enemies of men in his own organization who were afraid of his great power and influence, and jealous of him as a political rival. That some of his senatorial Republican associates should feel that the best service they could render their country would be to do all in their power to prevent such a man from being elevated to the Presidency … for while they knew he was an able man, they also knew that, according to his convictions of party duty and party obligations, he firmly believed he who served his party best served his country best…that he would have given the country an able administration is concurrent opinion of those who knew him best.

- John Roy Lynch, as quoted in The Facts of Reconstruction (1913), New York: The Neale Publishing Co., retrieved 2008-07-03.

- In contrast to the contemporary Black Americans, the Black Americans, in that era, were in solid support of the Republican Party. This was the party that fought the Northern and Southern Democrats to pass the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Although President Andrew Johnson tried to bamboozle Frederick Douglass to the Democrat side by making false or empty promises, he did not succeed. Douglass was no fool and was not going to let Johnson use him to gain the support of the Negroes in his effort to be 'elected' president. Frederick Douglass and other prominent Blacks threw their support to Ulysses S. Grant for president.

- Connie A. Miller, Sr., Frederick Douglass: American Hero (2008), p. 276.

- It was pretended at the time and it has since been asserted by historians and publicists that Mr. Johnson's Reconstruction policy was only a continuation of that of Mr. Lincoln. This is true only in a superficial sense, but not in reality. Mr. Lincoln had indeed put forth reconstruction plans which contemplated an early restoration of some of the rebel states. But he had done this while the Civil War was still going on, and for the evident purpose of encouraging loyal movements in those States and of weakening the Confederate State government there. Had he lived, he would have as ardently wished to stop bloodshed and to reunite as he ever did. But is it to be supposed for a moment that, seeing the late master class in the South intent upon subjecting the freedmen again to a system very much akin to slavery, Lincoln would have consented to abandon those freemen to the mercies of that master class?

- Carl Schurz in Reminiscences (1906).

- Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson, viewed the Radical Republican project as an insult to the white men to whom the United States truly belonged.

- Adam Serwer, The Cruelty is the Point (2021)

- Still convinced that most of the country was on his side, Johnson sank into paranoia, grandeur, and self-pity. In his "Swing Around the Circle" tour, Johnson gave angry speeches before raucous crowds, comparing himself to Lincoln, calling for some Radical Republicans to be hanged as traitors, and blaming the New Orleans riot on those who had called for black suffrage in the first place, saying, "Every drop of blood that was shed is upon their skirts and they are responsible." He blocked the measures that Congress took up to protect the rights of the emancipated, describing them as racist against white people. He told black leaders that he was their "Moses," even as he denied their aspirations to full citizenship. Johnson had reason to believe, in a country that had only just abolished slavery, that the Radicals' attempt to create a multiracial democracy would be rejected by the electorate. What he did not expect was that in his incompetence, courseness, and vanity, he would end up discrediting his own racist crusade and would press the North into pursuing a program of racial justice that it had wanted to avoid.

- Adam Serwer, The Cruelty is the Point (2021)

- Just as the white North in the late 1860s turned against Andrew Johnson because his commitment to white supremacy threatened to render the bloody sacrifices of the Civil War meaningless, millions of Americans were able to connect Trump's callousness and bigotry to his inability to govern.

- Adam Serwer, The Cruelty is the Point (2021)

- like Andrew Johnson, Trump bet his political fortunes on his assumption that the majority of white Americans shared his fears and beliefs about black Americans. Like Johnson, Trump did not anticipate how his own behavior, and the behavior he enabled and encouraged, would discredit the cause he backed. He did not anticipate that the activists might succeed in convincing so many white Americans to see the protests as righteous and justified, that so many white Americans would understand police violence as an extension of his own cruelty, that the pandemic would open their eyes to deep-seated racial inequities.

- Adam Serwer, The Cruelty is the Point (2021)

- Never was a great malefactor so gently treated as Andrew Johnson. The people have been unwilling to blot the records of their country by mingling his crimes with their shame—shame for endurance for so long a time of his great crimes and misdemeanors. The committee have omitted entirely his wicked abuse of the patronage of the Government, his corruption of the voters of the nation by seducing them with the offers of office, and intimidating them by threats of expulsion, all for the purpose of making them abandon their honest principles and adopt the bastard policy which he had just conceived, a crime more heinous than that which brought many ancient agitators to the block. To this he was prompted by the same motive which made the angels fall. Soon after the death of Mr. Lincoln and the surrender of the so-called confederate army and possessions, the whole government of the territory, persons and property of the territory claimed and conquered from the so-called confederate States of America devolved upon the Congress of the United States, according to the most familiar and well-adjudicated principles of national and municipal law, leaving nothing for the President to do but execute the laws of Congress and govern them by military authority until Congress should otherwise direct. Yet Andrew Johnson, assuming to establish an empire for his own control and depriving Congress of its just prerogative did erect North Carolina and the other conquered territories into States and nations, giving them governments of his own creation and appointing over them rulers unknown to the laws of the United States, and who could not by any such laws hold any office therein. He fixed the qualifications of electors, directed who should hold office, and especially directed them to send representatives to both branches of Congress, ordering Congress to admit them when they should arrive. When Congress refused and asserted its sovereign prerogative to govern those territories, except during their military occupation, by their own inherent power, he treated their pretensions as idle and refused to obey them. When Congress subsequently passed acts dated, March 2, 1867, and their supplements, to reconstruct those governments under republican forms by the votes of the people, he pronounced them unconstitutional, and after they had become laws he advised the people not to obey them, thus seeking to defeat instead of to execute the laws of Congress. All this was done after Congress had declared these outlying States as possessing no governments which Congress could recognize, and that Congress alone had the power and control over them. This monstrous usurpation, worse than sedition and little short of treason, he adhered to, by declaring in his last annual message and at other times that there was no Congress, and that all their acts were unconstitutional. These, being much more fundamental offenses, and, in my judgment, much more worthy of punishment, because more fatal to the nation, the committee have omitted in their articles of impeachment, because they were determined to deal gently with the President.

- Thaddeus Stevens, Landmark Debates in Congress: From the Declaration of Independence to the War in Iraq. Washington: CQ Press, 2009, pp. 175-84.

- Encouraged by this impunity, the President proceeded to new acts of lawless violence and disregard of the express enactments of Congress. It is those acts, trivial by comparison, but grave in their positive character, for which the committee has chosen to call him to answer, knowing that there is enough among them, if half were omitted, to answer the great object and purpose of impeachment. That proceeding can reach only to the removal from office, and anything beyond what will effect that purpose, being unnecessary, may be looked upon as wanton cruelty. Hence the tender mercies of this committee have rested only on the most trifling crimes and misdemeanors which they could select from the official life of Andrew Johnson.

- Thaddeus Stevens, Landmark Debates in Congress: From the Declaration of Independence to the War in Iraq. Washington: CQ Press, 2009, pp. 175-84.

- This is one of the last great battles with slavery. Driven from the legislative chambers, driven from the field of war, this monstrous power has found a refuge in the executive mansion, where, in utter disregard of the Constitution and laws, it seeks to exercise its ancient, far-reaching sway. All this is very plain. Nobody can question it. Andrew Johnson is the impersonation of the tyrannical slave power. In him it lives again.

- Senator Charles Sumner during Johnson's impeachment trial (May 1868).

- Whatever may have been the opinion of the President at one time as to "good faith requiring the security of the freemen in their liberty and their property," it is now manifest from the character of his objections to this bill that he will approve no measures that will accomplish the object.

- Senator Lyman Trumbull, author of the Thirteenth Amendment responding to Johnson's veto of the Civil Rights Bill (March 1866).

- No man in Tennessee has done more than Andrew Johnson to create, to perpetuate and embitter in the minds of the Southern people, that feeling of jealousy and hostility against the free States, which has at length culminated in rebellion and civil war. Up to 1860, he had been for 20 years among the most bigoted and intolerant of the advocates of slavery and Southernism.

- The Nashville Press (February 1863).

- The history this man leaves is a rare one. His career was remarkable, even in this country; it would have been quite impossible in any other. It presents the spectacle of a man who never went to school a day in his life rising from a humble beginning as a tailor's apprentice through a long succession of posts of civil responsibility to the highest office in the land, and evincing his continued hold upon the popular heart by a subsequent election to the Senate in the teeth of a bitter personal and political opposition.... Whatever else may be said of him, his integrity and courage have been seldom questioned though often proved. He was by nature and temperament squarely disposed toward justice and the right, and was a determined warrior for his convictions. He erred from limitation of grasp and perception, perhaps, or through sore perplexity in trying times, but never weakly or consciously. He was always headstrong and 'sure he was right' even in his errors.

- Obituary in The New York Times (1 August 1875).

- the order [Special Field Order No. 15] was reversed by the next president, the white supremacist, former enslaver and Confederate sympathiser Andrew Johnson. Johnson, who wrote “This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am President, it shall be a government for white men" ordered that the land should be returned to its former owners: the men who had declared war on the United States.

- Working Class History (2020)

- During the Civil War, one of the nation's leading abolitionists was Republican Senator Henry Wilson, of Massachusetts, who would later serve as vice president during President Grant's second term. In December 1861, Mr. Wilson introduced a bill to abolish slavery in the District. The measure met with parliamentary obstacles from the adamantly pro-slavery Democratic Party, whom Republicans in those days referred to as the 'Slave-ocrats'. Most Democrats in Congress having resigned in order to join the Confederate rebellion, Wilson's measure sailed through the Senate. The abolitionist senator responsible for outmaneuvering Democrat opposition was Ben Wade, the Ohio Republican who six years later would have assumed the presidency had the bitterly racist Democratic President, Andrew Johnson, been convicted during his impeachment trial. In the House of Representatives, Democrats delayed passage with a series of stalling tactics. Finally, the majority leader, Thaddeus Stevens, bulldozed over Democrat opposition by calling the House into a committee of the whole. He stopped all other business in the House until Democrats relented and allowed a vote on the bill. Stevens, of Pennsylvania, is best known for his 'forty acres and a mule' proposal. Overall, 99 percent of Republicans in Congress voted to free the slaves in the District of Columbia, and 83 percent of Democrats voted to keep them in chains.

- Michael Zak, as quoted in "Who killed slavery?" (17 April 2006), by M. Zak, The Washington Times.

- This is how the Mexican Empire will perish, a creation based on the assumption of a southern triumph and which today finds itself singularly compromised by the opposite result. Even with a president less democratic than Mr. Johnson, the United States would never have tolerated the establishment at its gates of an absolute monarchy under the rule of a foreign dynasty. The misfortunes of the civil war did not allow them to oppose it when the facts were unfolding. Perhaps in order to avoid a war with France they will not attack the new order of things directly, but certainly they would do nothing to support it, and the disbandment of their armies will provide them with all the desirable means to overthrow it indirectly.

- The Mexican adventure of Maximilian and Charlotte through Belgian eyes. The Mexican Empire in the Newspaper Press (1864-1867). (Wim Bouw), The New Throne, Catholic Opposition The attitude of the United States was seen as crucial in Belgian opinion. And the reports about this became more hostile, no one doubted that the United States supported Juarez. Which would be one of the major reasons for Maximilian's fall. L’ Indépendance Belge, 18 mei 1865.

See also

External links

- White House Biography

- Brief biography at Spartacus

- Works by Andrew Johnson at Project Gutenberg

- US State of the Union Addresses

- Articles of Impeachment

- Vice Presidential biography, from the Senate Historical Office (PDF)

- Mr. Lincoln's White House: Andrew Johnson

- Andrew Johnson on Find-A-Grave

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/business/podcasts/presidential/pdfs/andrew-johnson-transcript.pdf

- ↑ https://www.nps.gov/anjo/learn/historyculture/timeline.htm "Andrew Johnson Timeline".

- ↑ https://www.elizabethton.com/2020/03/18/east-tennessee-history-the-death-of-a-president/ "East Tennessee History: The Death of a President"

- ↑ https://www.roadsideamerica.com/story/31395 "Andrew Johnson Died Here"

- ↑ http://www.cartercountyhistory.com/andrew-johnson.html "Andrew Johnson - Carter County Area History"