Freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is the concept of being able to speak freely without censorship. It is often regarded as an integral concept in modern democracies.

Quotes

edit1600s

edit- Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties.

- John Milton, Areopagitica: A Speech for the Liberty of Unlicens'd Printing, to the Parliament of England (published November 23, 1644).

1700s

edit- Freedom of speech is a principal pillar of a free government; when this support is taken away, the constitution of a free society is dissolved, and tyranny is erected on its ruins. Republics and limited monarchies derive their strength and vigor from a popular examination into the action of the magistrates.

- There is nothing so fretting and vexatious, nothing so justly TERRIBLE to tyrants, and their tools and abettors, as a FREE PRESS.

- Samuel Adams, (Boston Gazette, 1768) — cited in: Emord, Jonathan W. (1991). Freedom, Technology, and the First Amendment. Pacific Research Institute for Public Policy. p. 61.

- For if Men are to be precluded from offering their Sentiments on a matter, which may involve the most serious and alarming consequences, that can invite the consideration of Mankind, reason is of no use to us; the freedom of Speech may be taken away, and, dumb and silent we may be led, like sheep, to the Slaughter.

- George Washington, address to the officers of the army, Newburgh, New York (March 15, 1783); reported in John C. Fitzpatrick, ed, The Writings of George Washington (1938), vol. 26, p. 225.

- Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.

- Thomas Jefferson to Edward Carrington, January 16, 1787, The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1, General Correspondence, 1651-1827 (Library of Congress).

- The free communication of thoughts and of opinions is one of the most precious rights of man: any citizen thus may speak, write, print freely, except to respond to the abuse of this liberty, in the cases determined by the law.

- Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

- First Amendment to the United States Constitution. December 15, 1791.

- I would rather be exposed to the inconveniences attending too much liberty, than those attending too small a degree of it.

- Thomas Jefferson to Archibald Stuart, Philadelphia, December 23, 1791.

- Cited in Thomas Jefferson (2002). "1791". in Jerry Holmes. Thomas Jefferson: A Chronology of His Thoughts. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. p. 128. ISBN 0742521168 .

- Every man has a right to utter what he thinks truth, and every other man has a right to knock him down for it.

- Samuel Johnson, as quoted in James Boswell's The Life of Samuel Johnson, Vol. 1 (1791), p. 335.

- The power of communication of thoughts and opinions is the gift of God, and the freedom of it is the source of all science, the first fruits and the ultimate happiness of society; and therefore it seems to follow, that human laws ought not to interpose, nay, cannot interpose, to prevent the communication of sentiments and opinions in voluntary assemblies of men.

- Eyre, L.C.J., Hardy's Case (1794), 24 How. St. Tr. 206; reported in James William Norton-Kyshe, The Dictionary of Legal Quotations (1904), p. 99.

- To preserve the freedom of the human mind then and freedom of the press, every spirit should be ready to devote itself to martyrdom; for as long as we may think as we will, and speak as we think, the condition of man will proceed in improvement.

Cato's Letters, John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon (Letter Number 15, Of Freedom of Speech, That the Same is inseparable from Publick Liberty, February 4, 1720)

edit- Without Freedom of Thought, there can be no such Thing as Wisdom; and no such Thing as public Liberty, without Freedom of Speech; which is the Right of every Man, as far as by it, he does not hurt or control the Right of another. And this is the only Check it ought to suffer, and the only bounds it ought to know. This sacred Privilege is to essential to free Governments, that the Security of Property, and the Freedom of Speech always go together; and in those wretched Countries where a Man cannot call his Tongue his own, he can scarce call any Thing else his own. Whoever would overthrow the Liberty of a Nation, must begin by subduing the Freedom of Speech; a Thing terrible to Publick Traytors.

- That Men ought to speak well of their Governours is true, while their Governours, deserve to be well spoken of, but to do publick Mischief, without hearing of it, is only the Prerogative and Felicity of Tyranny: A free People will be shewing that they are so, by their Freedom of Speech.

- The Administration of Government, is nothing else but the Attendence of the Trustees of the People upon the Interest and Affairs of the People: And as it is the Part and Business of the People, for whole Sake alone all publick Matters are, or ought to be transacted, to see whether they be well or ill transacted, so it is the Interest, and ought to be the Ambition, of all honest Magistrates, to have their Deeds openly examined, and Publickly scann'd[.]

- Freedom of Speech is ever the Symptom, as well as the Effect of a good Government. In old Rome, all was left to the Judgment and Pleasure of the People, who examined the publick Proceedings with such Discretion, & censured those who administred them with such Equity and Mildness, that in the space of Three Hundred Years, not five publick Ministers suffered unjustly. Indeed whenever the Commons proceeded to Violence, the great Ones had been the Agressors.

- Guilt only dreads Liberty of Speech, which drags it out of its lurking Holes, and exposes its Deformity and Horrour to Day-light.

- The best Princes have ever encouraged and Promoted Freedom of Speech; they know that upright Measures would defend themselves, and that all upright Men would defend them.

- Misrepressentation of publick Measures is easily overthrown, by representing publick Measures truly; when they are honest, they ought to be publickly known, that they may be publickly commended, but if they are knavish or pernicious, they ought to be publickly exposed, in order to be pubickly detested.

- Freedom of speech is the great bulwark of liberty; they prosper and die together: And it is the terror of traitors and oppressors, and a barrier against them. It produces excellent writers, and encourages men of fine genius.

- All Ministers … who were Oppressors, or intended to be Oppressors, have been loud in their Complaints against Freedom of Speech, and the License of the Press; and always restrained, or endeavored to restrain, both.

1800s

edit- Error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it.

- Thomas Jefferson, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1801.

- The diffusion of information and arraignment of all abuses at the bar of the public reason; freedom of religion; freedom of the press, and freedom of person under the protection of the habeas corpus, and trial by juries impartially selected. These principles form the bright constellation which has gone before us and guided our steps through an age of revolution and reformation. The wisdom of our sages and blood of our heroes have been devoted to their attainment. They should be the creed of our political faith, the text of civic instruction, the touchstone by which to try the services of those we trust; and should we wander from them in moments of error or of alarm, let us hasten to retrace our steps and to regain the road which alone leads to peace, liberty, and safety.

- Thomas Jefferson, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1801.

- When people talk of the freedom of writing, speaking, or thinking, I cannot choose but laugh. No such thing ever existed. No such thing now exists; but I hope it will exist. But it must be hundreds of years after you and I shall write and speak no more.

- John Adams, in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, 15 July, 1817.

- May it be to the world, what I believe it will be, (to some parts sooner, to others later, but finally to all,) the signal of arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self-government. That form which we have substituted, restores the free right to the unbounded exercise of reason and freedom of opinion. All eyes are opened, or opening, to the rights of man.

- Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Roger Weightman, June 24, 1826, in The Life and Selected Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Adrienne Koch and William Peden (New York: Modern Library, 1944), p. 729.

- A popular Government without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy, or perhaps both. Knowledge will forever govern ignorance: And a people who mean to be their own Governors, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.

- I know of no country in which there is so little independence of mind and real freedom of discussion as in America.

- Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Volume I (1835), Chapter XV

- In America the majority raises formidable barriers around the liberty of opinion; within these barriers an author may write what he pleases, but woe to him if he goes beyond them.

- Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Volume I (1835), Chapter XV

- How absurd men are! They never use the liberties they have, they demand those they do not have. They have freedom of thought, they demand freedom of speech.

- Soren Kierkegaard Either/Or Part I (1843), Swenson p. 19.

- People hardly ever make use of the freedom they have, for example, freedom of thought; instead they demand freedom of speech as a compensation.

- Soren Kierkegaard, as quoted in The Fitzhenry & Whiteside Book of Quotations (1981), p. 172.

- And I honor the man who is willing to sink

Half his present repute for the freedom to think,

And, when he has thought, be his cause strong or weak,

Will risk t'other half for the freedom to speak.- James Russell Lowell, A Fable for Critics (1848), Pt. V - Cooper, st. 3.

- No law shall be passed restraining the free expression of opinion, or restricting the right to speak, write or print freely on any subject whatever.

- Oregon Constitution, (1857), Article I, Section 8.

- The class which has the means of material production at its disposal has control over the means of mental production, so that in consequence the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are, in general, subject to it.

- Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The German Ideology ca. April or early May 1846

- Strange it is that men should admit the validity of the arguments for free speech but object to their being "pushed to an extreme", not seeing that unless the reasons are good for an extreme case, they are not good for any case.

- John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859) Ch. 2, Mill (1985). On Liberty. Penguin. pp. p. 108.

- If any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility. … Though the silenced opinion be an error, it may, and very commonly does, contain a portion of truth; and since the general or prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only by the collision of adverse opinions that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied … Even if the received opinion be not only true, but the whole truth; unless it is suffered to be, and actually is, vigorously and earnestly contested, it will, by most of those who receive it, be held in the manner of a prejudice, with little comprehension [of] or feeling [for] its rational grounds.

- John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, (1859).

- He who stifles free discussion, secretly doubts whether what he professes to believe is really true.

- Wendell Phillips, oration delivered at Daniel O'Connell celebration, Boston (6 August 1870), published in Wendell Phillips: The Agitator (1890) by William Carlos Martyn, p. 563

- I do not believe that the tendency is to make men and women brave and glorious when you tell them that there are certain ideas upon certain subjects that they must never express; that they must go through life with a pretence as a shield; that their neighbors will think much more of them if they will only keep still; and that above all is a God who despises one who honestly expresses what he believes. For my part, I believe men will be nearer honest in business, in politics, grander in art — in everything that is good and grand and beautiful, if they are taught from the cradle to the coffin to tell their honest opinion.

- Robert G. Ingersoll, The Great Infidels (1881)

- Standing in the presence of the Unknown, all have the same right to think, and all are equally interested in the great questions of origin and destiny. All I claim, all I plead for, is liberty of thought and expression. That is all. I do not pretend to tell what is absolutely true, but what I think is true. I do not pretend to tell all the truth.

I do not claim that I have floated level with the heights of thought, or that I have descended to the very depths of things. I simply claim that what ideas I have, I have a right to express; and that any man who denies that right to me is an intellectual thief and robber. That is all.- Robert G. Ingersoll, The Liberty of Man, Woman and Child (1877)

- I would not wish to live in a world where I could not express my honest opinions. Men who deny to others the right of speech are not fit to live with honest men.

I deny the right of any man, of any number of men, of any church, of any State, to put a padlock on the lips — to make the tongue a convict. I passionately deny the right of the Herod of authority to kill the children of the brain.

- I am a believer in liberty. That is my religion — to give to every other human being every right that I claim for myself, and I grant to every other human being, not the right — because it is his right — but instead of granting I declare that it is his right, to attack every doctrine that I maintain, to answer every argument that I may urge — in other words, he must have absolute freedom of speech.

- I would defend the freedom of speech. And why? Because no attack can be answered by force, no argument can be refuted by a blow, or by imprisonment, or by fine. You may imprison the man, but the argument is free; you may fell the man to the earth, but the statement stands.

- Without free speech no search for Truth is possible; without free speech no discovery of Truth is useful; without free speech progress is checked, and the nations no longer march forward towards the nobler life which the future holds for man. Better a thousandfold abuse of free speech than denial of free speech. The abuse dies in a day; the denial slays the life of the people and entombs the hope of the race.

- Charles Bradlaugh, Speech at Hall of Science c.1880 quoted in An Autobiography of Annie Besant; reported in Edmund Fuller, Thesaurus of Quotations (1941), p. 398; reported as unverified in Respectfully Quoted: A Dictionary of Quotations (1989).

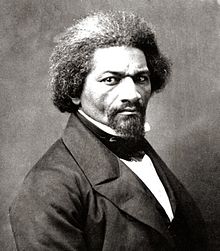

- Liberty is meaningless where the right to utter one's thoughts and opinions has ceased to exist. That, of all rights, is the dread of tyrants. It is the right which they first of all strike down. They know its power. Thrones, dominions, principalities, and powers, founded in injustice and wrong, are sure to tremble, if men are allowed to reason of righteousness, temperance, and of a judgment to come in their presence. Slavery cannot tolerate free speech.

- Frederick Douglass, Plea for Free Speech in Boston (8 June 1880)

- It is by the goodness of God that in our country we have those three unspeakably precious things: freedom of speech, freedom of conscience, and the prudence never to practice either of them.

- Mark Twain, Following the Equator, Vol. 1 (1897), ch. 20.

1900s

edit- I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.

- Evelyn Beatrice Hall, Ch. 7 : Helvetius: The Contradiction (1906), p. 199. Often misattributed to Voltaire.

- Anarchism says, Make no laws whatever concerning speech, and speech will be free; so soon as you make a declaration on paper that speech shall be free, you will have a hundred lawyers proving that "freedom does not mean abuse, nor liberty license"; and they will define and define freedom out of existence. Let the guarantee of free speech be in every man's determination to use it, and we shall have no need of paper declarations.

- Voltairine de Cleyre , "Anarchism & American Traditions" in Mother Earth (December 1908/January 1909)

- Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high

Where knowledge is free

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments

By narrow domestic walls

Where words come out from the depth of truth

Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way

Into the dreary desert sand of dead habit

Where the mind is led forward by thee:Into ever-widening thought and action

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.- A poem by Rabindranath Tagore about freedom of expression. The original Bengali language poem, "Chitto jetha bhayashunyo", was published in 1910 and included in the collection Gitanjali by Tagore.

- Without an unfettered press, without liberty of speech, all the outward forms and structures of free institutions are a sham, a pretense—the sheerest mockery. If the press is not free; if speech is not independent and untrammelled; if the mind is shackled or made impotent through fear, it makes no difference under what form of government you live you are a subject and not a citizen. Republics are not in and of themselves better than other forms of government except in so far as they carry with them and guarantee to the citizen that liberty of thought and action for which they were established.

- William E. Borah, remarks in the Senate (April 19, 1917), Congressional Record, vol. 55, p. 837.

- I realize that, in speaking to you this afternoon, there are certain limitations placed upon the right of free speech. I must be exceedingly careful, prudent, as to what I say, and even more careful and prudent as to how I say it. I may not be able to say all I think; but I am not going to say anything that I do not think. I would rather a thousand times be a free soul in jail than to be a sycophant and coward in the streets.

- Eugene V. Debs, speech to the Socialist party of Ohio state convention, Canton, Ohio (June 16, 1918); republished in Jean Y. Tussey, ed., Eugene V. Debs Speaks (1970), p. 244. This was Debs's most famous speech. It was a socialist antiwar speech while the United States was at war, and it was used against him at his trial. Debs was convicted under the Espionage Law and sentenced to 10 years in prison. President Warren G. Harding commuted the sentence in 1921.

- I have always been among those who believed that the greatest freedom of speech was the greatest safety, because if a man is a fool, the best thing to do is to encourage him to advertise the fact by speaking. It cannot be so easily discovered if you allow him to remain silent and look wise, but if you let him speak, the secret is out and the world knows that he is a fool. So it is by the exposure of folly that it is defeated; not by the seclusion of folly, and in this free air of free speech men get into that sort of communication with one another which constitutes the basis of all common achievement.

- Woodrow Wilson, "That Quick Comradeship of Letters," address at the Institute of France, Paris (May 10, 1919); in Ray Stannard Baker and William E. Dodd, eds., The Public Papers of Woodrow Wilson (1927), vol. 5, p. 484.

- The general rule of law is, that the noblest of human productions — knowledge, truths ascertained, conceptions and ideas — become, after voluntary communication to others, free as the air to common use.

- Freedom of expression is the matrix, the indispensable condition, of nearly every other form of freedom.

- Benjamin N. Cardozo, Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U.S. 319, 327, (1937)

- But arms – instrumentalities, as President Wilson called them – are not sufficient by themselves. We must add to them the power of ideas. People say we ought not to allow ourselves to be drawn into a theoretical antagonism between Nazidom and democracy; but the antagonism is here now. It is this very conflict of spiritual and moral ideas which gives the free countries a great part of their strength. You see these dictators on their pedestals, surrounded by the bayonets of their soldiers and the truncheons of their police. On all sides they are guarded by masses of armed men, cannons, aeroplanes, fortifications, and the like – they boast and vaunt themselves before the world, yet in their hearts there is unspoken fear. They are afraid of words and thoughts; words spoken abroad, thoughts stirring at home – all the more powerful because forbidden – terrify them. A little mouse of thought appears in the room, and even the mightiest potentates are thrown into panic. They make frantic efforts to bar our thoughts and words; they are afraid of the workings of the human mind. Cannons, airplanes, they can manufacture in large quantities; but how are they to quell the natural promptings of human nature, which after all these centuries of trial and progress has inherited a whole armoury of potent and indestructible knowledge?

- Winston Churchill, Broadcast to the United States and to London, 16 October 1938

- So we must beware of a tyranny of opinion which tries to make only one side of a question the one which may be heard. Everyone is in favour of free speech. Hardly a day passes without its being extolled, but some people’s idea of it is that they are free to say what they like, but if anyone says anything back, that is an outrage.

- Winston Churchill, October 13, 1943 Hansard, United Kingdom Parliament, Commons, Coalmining Situation, HC Deb, volume 392, cc920-1012.

- After all, if freedom of speech means anything, it means a willingness to stand and let people say things with which we disagree, and which do weary us considerably.

- Zechariah Chafee; in Chafee (1920). Freedom of Speech. Harcourt, Brace and Howe. pp. p. 366.

- The Constitution is a delusion and a snare if the weakest and humblest man in the land cannot be defended in his right to speak and his right to think as much as the strongest in the land.

- Clarence Darrow Address to the court in People v. Lloyd (1920)

- When men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good is better reached by free trade in ideas — that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out. That at any rate is the theory of our Constitution.

- But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done…. The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic. It does not even protect a man from an injunction against uttering words that may have all the effect of force…. The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree.

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 52 (1919).

- Often paraphrased as: "Freedom of speech does not give a person the right to shout 'Fire!' in a crowded theatre."

- Freiheit ist immer Freiheit der Andersdenkenden.

- Freedom is always the freedom of dissenters.

- Rosa Luxemburg, Sources: Die russische Revolution. Eine kritische Würdigung, Berlin 1920 p. 109 and in Rosa Luxemburg - Gesammelte Werke Vol. 4, p. 359, Footnote 3, Dietz Verlag Berlin (Ost), 1983

- Variant: "Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently."

- So long as you are a slave to the opinions of the many you have not yet approached freedom or tasted its nectar… But I do not mean by this that we ought to be shameless before all men and to do what we ought not; but all that we refrain from and all that we do, let us not do or refrain from merely because it seems to the multitude somehow honorable or base, but because it is forbidden by reason and the god within us.

- Julian, As quoted in The Works of the Emperor Julian (1923) by Wilmer Cave France Wright, p. 47

- Herein lies the value of free speech. It makes concealment difficult, and, in the long run, impossible. One heretic, if he is right, is as good as a host. He is bound to win in the long run. It is thus no wonder that foes of the enlightenment always begin their proceedings by trying to deny free speech to their opponents. It is dangerous to them and they know it. So they have at it by accusing these opponents of all sorts of grave crimes and misdemeanors, most of them clearly absurd – in other words, by calling them names and trying to scare them.

- H. L. Mencken, The Sad Case of Tennessee in the Chicago Tribune (March 14, 1926)

- It is the function of speech to free men from the bondage of irrational fears.

- Louis Brandeis, (Whitney v. California, 1927).

- Those who won our independence believed that the final end of the State was to make men free to develop their faculties; and that in its government the deliberative forces should prevail over the arbitrary. They valued liberty both as an end and as a means. They believed liberty to be the secret of happiness and courage to be the secret of liberty. They believed that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth; that without free speech and assembly discussion would be futile; that with them, discussion affords ordinarily adequate protection against the dissemination of noxious doctrine; that the greatest menace to freedom is an inert people; that public discussion is a political duty; and that this should be a fundamental principle of the American government.

- Louis Brandeis, (Whitney v. California, 1927).

- Those who won our independence by revolution were not cowards. They did not fear political change. They did not exalt order at the cost of liberty. To courageous, self-reliant men, with confidence in the power of free and fearless reasoning applied through the processes of popular government, no danger flowing from speech can be deemed clear and present, unless the incidence of the evil apprehended is so imminent that it may befall before there is opportunity for full discussion. If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.

- Louis Brandeis, (Whitney v. California, 1927).

- If there is any principle of the Constitution that more imperatively calls for attachment than any other, it is the principle of free thought — not free thought for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought we hate.

- It is no longer open to doubt that the liberty of the press, and of speech, is within the liberty safeguarded by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment from invasion by state action. It was found impossible to conclude that this essential personal liberty of the citizen was left unprotected by the general guaranty of fundamental rights of person and property.

- Charles Evans Hughes, (Near v. Minnesota, 1931).

- So, dear friend, put fear out of your heart. This nation will survive, this state will prosper, the orderly business of life will go forward if only men can speak in whatever way given them to utter what their hearts hold—by voice, by posted card, by letter or by press. Reason never has failed men. Only force and repression have made the wrecks in the world.

- William Allen White, "To an Anxious Friend," editorial, The Emporia (Kansas) Gazette (July 27, 1922), Russell H. Fitzgibbon, compiler, White, Forty Years on Main Street (1937), p. 285.

- The liberty of the press is not confined to newspapers and periodicals. It necessarily embraces pamphlets and leaflets. … the press in its historic connotation comprehends every sort of publication which affords a vehicle of information and opinion.

- Charles Evans Hughes, Lovell v. City of Griffin, 303 U.S. 444 (1938).

- The freedom of speech and of the press, which are secured by the First Amendment against abridgment by the United States, are among the fundamental personal rights and liberties which are secured to all persons by the Fourteenth Amendment against abridgment by a state. The safeguarding of these rights to the ends that men may speak as they think on matters vital to them and that falsehoods may be exposed through the processes of education and discussion is essential to free government. Those who won our independence had confidence in the power of free and fearless reasoning and communication of ideas to discover and spread political and economic truth.

- Frank Murphy (1940). Thornhill v. Alabama. Supreme Court of the United States. pp. 310 U.S. 88, 95.

- Without general elections, without freedom of the press, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, without the free battle of opinions, life in every public institution withers away, becomes a caricature of itself, and bureaucracy rises as the only deciding factor.

- Rosa Luxemburg, Reported in Paul Froelich, Die Russiche Revolution (1940).

- We look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms. The first is freedom of speech and expression—everywhere in the world. The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way—everywhere in the world. The third is freedom from want... The fourth is freedom from fear.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, message to Congress, 6 January 1941.

- Back of the guarantee of free speech lay faith in the power of an appeal to reason by all the peaceful means for gaining access to the mind. It was in order to avert force and explosions due to restrictions upon rational modes of communication that the guarantee of free speech was given a generous scope. But utterance in a context of violence can lose its significance as an appeal to reason and become part of an instrument of force. Such utterance was not meant to be sheltered by the Constitution.

- Felix Frankfurter, Milk Wagon Drivers Union of Chicago, Local 753. v. Meadowmoor Dairies, Inc., 312 U.S. 287, 293 (1941).

- Compulsory unification of opinion achieves only the unanimity of the graveyard.

- Robert H. Jackson (1943). West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette. Supreme Court of the United States. pp. 319 U.S. 624, 638.

- The very purpose of a Bill of Rights was to withdraw certain subjects from the vicissitudes of political controversy, to place them beyond the reach of majorities, and to establish them as legal principles to be applied by the courts. / One's right to life, liberty, and property, to free speech, a free press, freedom of worship and assembly, and other fundamental rights may not be submitted to vote; they depend on the outcome of no elections.

- Robert H. Jackson (1943). West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette. Supreme Court of the United States. pp. 319 U.S. 624, 638.

- Take away freedom of speech, and the creative faculties dry up.

- The relative freedom which we enjoy depends of public opinion. The law is no protection. Governments make laws, but whether they are carried out, and how the police behave, depends on the general temper in the country. If large numbers of people are interested in freedom of speech, there will be freedom of speech, even if the law forbids it; if public opinion is sluggish, inconvenient minorities will be persecuted, even if laws exist to protect them.

- George Orwell, "Freedom of the Park", Tribune (7 December 1945)

- I want freedom for full expression of my personality.

- Mahatma Gandhi in Jews and Palestine (July 1946), as quoted in The Gandhi Reader: A Sourcebook of His Life and Writings, p. 327

- Threats to freedom of speech, writing and action, though often trivial in isolation, are cumulative in their effect and, unless checked, lead to a general disrespect for the rights of the citizen.

- George Orwell, "The Freedom Defence Committee" in The Socialist Leader (18 September 1948); also in The Collected Essays, Journalism, & Letters, George Orwell; Vol. IV : In front of your nose, 1945-1950 (2000), p. 447

- Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

- United Nations General Assembly (December 10, 1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Palais de Chaillot, Paris: United Nations. pp. Article 19.Text

- The vitality of civil and political institutions in our society depends on free discussion. As Chief Justice Hughes wrote in De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353, 365, 260, it is only through free debate and free exchange of ideas that government remains responsive to the will of the people and peaceful change is effected. The right to speak freely and to promote diversity of ideas and programs is therefore one of the chief distinctions that sets us apart from totalitarian regimes.

Accordingly a function of free speech under our system of government is to invite dispute. It may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger. Speech is often provocative and challenging. It may strike at prejudices and preconceptions and have profound unsettling effects as it presses for acceptance of an idea. That is why freedom of speech, though not absolute, Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, supra, 315 U.S. at pages 571-572, 62 S.Ct. at page 769, is nevertheless protected against censorship or punishment, unless shown likely to produce a clear and present danger of a serious substantive evil that rises far above public inconvenience, annoyance, or unrest. See Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252, 262, 193, 159 A.L.R. 1346; Craig v. Harney, 331 U.S. 367, 373, 1253. There is no room under our Constitution for a more restrictive view. For the alternative would lead to standardization of ideas either by legislatures, courts, or dominant political or community groups.Terminiello, 337 U.S. at 4-5.- William O. Douglas, Majority opinion, Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949) at 4-5.

- Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four. If that is granted, all else follows.

- George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949)

- If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.

- George Orwell, Original preface to Animal Farm; as published in George Orwell : Some Materials for a Bibliography (1953) by Ian R. Willison

- Restriction of free thought and free speech is the most dangerous of all subversions. It is the one un-American act that could most easily defeat us.

- William O. Douglas, "The One Un-American Act," Speech to the Author's Guild Council in New York, on receiving the 1951 Lauterbach Award (December 3, 1952) [1]

- The sound of tireless voices is the price we pay for the right to hear the music of our own opinions.

- Adlai Stevenson, Adlai's Almanac: The Wit and Wisdom of Stevenson of Illinois (1952), p. 43.

- I yield to no man—if I may borrow that majestic parliamentary phrase—I yield to no man in my belief in the principle of free debate, inside or outside the halls of Congress. The sound of tireless voices is the price we pay for the right to hear the music of our own opinions. But there is also, it seems to me, a moment at which democracy must prove its capacity to act. Every man has a right to be heard; but no man has the right to strangle democracy with a single set of vocal cords.

- Adlai Stevenson, speech to the state committee of the Liberal party, New York City (August 28, 1952); in The Papers of Adlai E. Stevenson (1974), vol. 4, p. 63.

- History indicates that individual liberty is intermittently subjected to extraordinary perils. Even countries dedicated to government by the people are not free from such cyclical dangers. ... Test oaths are notorious tools of tyranny. When used to shackle the mind they are, or at least they should be, unspeakably odious to a free people. Test oaths are made still more dangerous when combined with bills of attainder which like this Oklahoma statute impose pains and penalties for past lawful associations and utterances.... Governments need and have ample power to punish treasonable acts. But it does not follow that they must have a further power to punish thought and speech as distinguished from acts. Our own free society should never forget that laws which stigmatize and penalize thought and speech of the unorthodox have a way of reaching, ensnaring and silencing many more people than at first intended. We must have freedom of speech for all or we will in the long run have it for none but the cringing and the craven. And I cannot too often repeat my belief that the right to speak on matters of public concern must be wholly free or eventually be wholly lost.

- Hugo Black (December 15, 1952), Weiman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 at 192-194 (Black, J., concurring).

- Laws alone cannot secure freedom of expression; in order that every man may present his views without penalty, there must be a spirit of tolerance in the entire population.

- Albert Einstein, Ideas and Opinions by Albert Einstein (1954), p. 32.

- For in the absence of debate unrestricted utterance leads to the degradation of opinion. By a kind of Gresham's law the more rational is overcome by the less rational, and the opinions that will prevail will be those which are held most ardently by those with the most passionate will. For that reason the freedom to speak can never be maintained merely by objecting to interference with the liberty of the press, of printing, of broadcasting, of the screen. It can be maintained only by promoting debate.

- Walter Lippmann, Essays in the Public Philosophy (1955), chapter 9, section 3, p. 129–30.

- That there is a social problem presented by obscenity is attested by the expression of the legislatures of the forty-eight States, as well as the Congress. To recognize the existence of a problem, however, does not require that we sustain any and all measures adopted to meet that problem. The history of the application of laws designed to suppress the obscene demonstrates convincingly that the power of government can be invoked under them against great art or literature, scientific treatises, or works exciting social controversy. Mistakes of the past prove that there is a strong countervailing interest to be considered in the freedoms guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

- If the First Amendment guarantee of freedom of speech and press is to mean anything, it must allow protests even against the moral code that the standard of the day sets for the community.

- The standard of what offends 'the common conscience of the community' conflicts … with the command of the First Amendment. … Certainly that standard would not be an acceptable one if religion, economics, politics or philosophy were involved. How does it become a constitutional standard when literature treating with sex is concerned? / Any test that turns on what is offensive to the community's standards is too loose, too capricious, too destructive of freedom of expression to be squared with the First Amendment. Under that test, juries can censor, suppress, and punish what they don't like, provided the matter relates to 'sexual impurity' or has a tendency to 'excite lustful thoughts.' This is community censorship in one of its worst forms...

- William O. Douglas, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (Roth v. United States, 1957)

- We are not afraid to entrust the American people with unpleasant facts, foreign ideas, alien philosophies, and competitive values. For a nation that is afraid to let its people judge the truth and falsehood in an open market is a nation that is afraid of its people.

- John F. Kennedy, “Remarks on the 20th Anniversary of the Voice of America (February 26, 1962)

- We are required in this case to determine for the first time the extent to which the constitutional protections for speech and press limit a State's power to award damages in a libel action brought by a public official against critics of his official conduct.

- William J. Brennan, Jr., Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 1964).

- [There exists a] profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.

- William J. Brennan, Jr., Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 1964).

- Authoritative interpretations of the First Amendment guarantees have consistently refused to recognize an exception for any test of truth — whether administered by judges, juries, or administrative officials — and especially one that puts the burden of proving truth on the speaker.

- William J. Brennan, Jr., Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 1964).

- The censor is always quick to justify his function in terms that are protective of society. But the First Amendment, written in terms that are absolute, deprives the States of any power to pass on the value, the propriety, or the morality of a particular expression.

- William O. Douglas, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (Memoirs v. Massachusetts, 1966).

- The dissemination of the individual's opinions on matters of public interest is for us, in the historic words of the Declaration of Independence, an 'unalienable right' that 'governments are instituted among men to secure.' History shows us that the Founders were not always convinced that unlimited discussion of public issues would be 'for the benefit of all of us' but that they firmly adhered to the proposition that the 'true liberty of the press' permitted 'every man to publish his opinion'.

- John Marshall Harlan II, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (Curtis Publishing Company v. Butts, 1967).

- The free communication of thoughts and opinions is one of the invaluable rights of man, and every citizen may freely speak, write and print on any subject, being responsible for the abuse of that liberty.

- Somewhere I read of the freedom of assembly. Somewhere I read of the freedom of speech. Somewhere I read of the freedom of the press. Somewhere I read that the greatness of America is the right to protest for right. And so just as I say, we aren't going to let any injunction turn us around. We are going on.

- Martin Luther King, Jr. I've Been to the Mountaintop (1968) >Speech delivered at Bishop Charles Mason Temple in Memphis, Tennessee (3 April 1968)

- Whatever may be the justifications for other statutes regulating obscenity, we do not think they reach into the privacy of one's own home. If the First Amendment means anything, it means that a State has no business telling a man, sitting alone in his own house, what books he may read or what films he may watch. Our whole constitutional heritage rebels at the thought of giving government the power to control men's minds.

- Thurgood Marshall, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (Stanley v. Georgia, 1969).

- First Amendment rights, applied in light of the special characteristics of the school environment, are available to teachers and students. It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.

- In order for the State in the person of school officials to justify prohibition of a particular expression of opinion, it must be able to show that its action was caused by something more than a mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint.

- Abe Fortas, (Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, 1969).

- Under our Constitution, free speech is not a right that is given only to be so circumscribed that it exists in principle but not in fact. Freedom of expression would not truly exist if the right could be exercised only in an area that a benevolent government has provided as a safe haven for crackpots. The Constitution says that Congress (and the States) may not abridge the right to free speech. This provision means what it says. We properly read it to permit reasonable regulation of speech-connected activities in carefully restricted circumstances. But we do not confine the permissible exercise of First Amendment rights to a telephone booth or the four corners of a pamphlet, or to supervised and ordained discussion in a school classroom.

- Abe Fortas, (Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, 1969).

- The word "security" is a broad, vague generality whose contours should not be invoked to abrogate the fundamental law embodied in the First Amendment. The guarding of military and diplomatic secrets at the expense of informed representative government provides no real security for our Republic.

- Hugo Black, (New York Times Company v. United States, 1971).

- The security of the Nation is not at the ramparts alone. Security also lies in the value of our free institutions. A cantankerous press, an obstinate press, an ubiquitous press must be suffered by those in authority in order to preserve the even greater values of freedom of expression and the right of the people to know. In this case there has been no attempt by the Government at political suppression. There has been no attempt to stifle criticism. Yet in the last analysis it is not merely the opinion of the editorial writer or of the columnist which is protected by the First Amendment. It is the free flow of information so that the public will be informed about the Government and its actions. These are troubled times. There is no greater safety valve for discontent and cynicism about the affairs of Government than freedom of expression in any form.

- Murray Gurfein June 19, 1971 in United States v. N.Y. Times Co., 328 F. Supp. 324, 331 (S.D.N.Y. 1971).

- ... I would not in this case decide, even by way of dicta, that the Government may lawfully seize literary material intended for the purely private use of the importer. The terms of the statute appear to apply to an American tourist who, after exercising his constitutionally protected liberty to travel abroad, returns home with a single book in his luggage, with no intention of selling it or otherwise using it, except to read it. If the Government can constitutionally take the book away from him as he passes through customs, then I do not understand the meaning of Stanley v. Georgia.

- Effective self-government cannot succeed unless the people are immersed in a steady, robust, unimpeded, and uncensored flow of opinion and reporting which are continuously subjected to critique, rebuttal, and reexamination.

- William O. Douglas, (Branzburg v. Hayes, 1972).

- The people, the ultimate governors, must have absolute freedom of, and therefore privacy of, their individual opinions and beliefs regardless of how suspect or strange they may appear to others. Ancillary to that principle is the conclusion that an individual must also have absolute privacy over whatever information he may generate in the course of testing his opinions and beliefs.

- William O. Douglas, (Branzburg v. Hayes, 1972).

- It is my view that there is no "compelling need" that can be shown which qualifies the reporter's immunity from appearing or testifying before a grand jury, unless the reporter himself is implicated in a crime. His immunity, in my view, is therefore quite complete, for, absent his involvement in a crime, the First Amendment protects him against an appearance before a grand jury, and, if he is involved in a crime, the Fifth Amendment stands as a barrier. … And since, in my view, a newsman has an absolute right not to appear before a grand jury, it follows for me that a journalist who voluntarily appears before that body may invoke his First Amendment privilege to specific questions.

- William O. Douglas, (Branzburg v. Hayes, 1972).

- At any given moment there is an orthodoxy, a body of ideas which it is assumed that all right-thinking people will accept without question. It is not exactly forbidden to say this, that or the other, but it is ‘not done’ to say it, just as in mid-Victorian times it was ‘not done’ to mention trousers in the presence of a lady. Anyone who challenges the prevailing orthodoxy finds himself silenced with surprising effectiveness. A genuinely unfashionable opinion is almost never given a fair hearing.

- Controversy may rage as long as it adheres to the presuppositions that define the consensus of elites, and it should furthermore be encouraged within these bounds, thus helping to establish these doctrines as the very condition of thinkable thought while reinforcing the belief that freedom reigns.

- Noam Chomsky, Necessary Illusions (1989)

- Goebbels was in favor of freedom of speech for views he liked. So was Stalin. If you're in favor of freedom of speech, that means you're in favor of freedom of speech precisely for views you despise.

- Noam Chomsky, Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media, 1992

- The smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion, but allow very lively debate within that spectrum—even encourage the more critical and dissident views. That gives people the sense that there's free thinking going on, while all the time the presuppositions of the system are being reinforced by the limits put on the range of the debate.

- Noam Chomsky, The Common Good, 1998

- Prior restraints on speech and publication are the most serious and least tolerable infringement on First Amendment Rights.

- We conclude that public figures and public officials may not recover for the tort of intentional infliction of emotional distress by reason of publications such as the one here at issue without showing, in addition, that the publication contains a false statement of fact which was made with 'actual malice,' i.e., with knowledge that the statement was false or with reckless disregard as to whether or not it was true. This is not merely a 'blind application' of the New York Times standard, see Time, Inc. v. Hill, 385 U.S. 374, 390 (1967); it reflects our considered judgment that such a standard is necessary to give adequate "breathing space" to the freedoms protected by the First Amendment.

- At the heart of the First Amendment is the recognition of the fundamental importance of the free flow of ideas and opinions on matters of public interest and concern. The freedom to speak one's mind is not only an aspect of individual liberty – and thus a good unto itself – but also is essential to the common quest for truth and the vitality of society as a whole. We have therefore been particularly vigilant to ensure that individual expressions of ideas remain free from governmentally imposed sanctions.

- Chief Justice William Rehnquist, Hustler Magazine v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46 (1988).

- There is no indication - either in the text of the Constitution or in our cases interpreting it - that a separate judicial category exists for the American flag alone. … We decline … therefore to create for the flag an exception to the joust of principles protected by the First Amendment.

- If there is a bedrock principle of the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable.

- Justice William J. Brennan, Jr., Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989).

- What is freedom of expression? Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist.

- Salman Rushdie, In Good Faith (1990), p. 6.

- Inconvenience does not absolve the government of its obligation to tolerate speech.

- Anthony Kennedy, International Society for Krishna Consciousness v. Lee, 505 U.S. 672, 672 (1992) (concurring).

- As a young constitutional lawyer, I was put to the first amendment test when I was called on to defend racists and neo-Nazis. I really had no choice. Surely now we know that none of us do. Free speech is unequivocal, unpolitical, and indivisible.

- Eleanor Holmes Norton, "Support for Free Speech", Congressional Record, Volume 141, Number 71 (Tuesday, May 2, 1995), United States House of Representatives, Page H4448.

- At the core of freedom of expression lies the need to ensure that truth and the common good are attained, whether in scientific and artistic endeavors or in the process of determining the best course to take in our political affairs. Since truth and the ideal form of political and social organization can rarely, if at all, be identified with absolute certainty, it is difficult to prohibit expression without impeding the free exchange of potentially valuable information. Nevertheless, the argument from truth does not provide convincing support for the protection of hate propaganda. Taken to its extreme, this argument would require us to permit the communication of all expression, it being impossible to know with absolute certainty which factual statements are true, or which ideas obtain the greatest good. The problem with this extreme position, however, is that the greater the degree of certainty that a statement is erroneous or mendacious, the less its value in the quest for truth. Indeed, expression can be used to the detriment of our search for truth; the state should not be the sole arbiter of truth, but neither should we overplay the view that rationality will overcome all falsehoods in the unregulated marketplace of ideas. There is very little chance that statements intended to promote hatred against an identifiable group are true, or that their vision of society will lead to a better world. To portray such statements as crucial to truth and the betterment of the political and social milieu is therefore misguided.

- Chief Justice Brian Dickson (for the majority), Supreme Court of Canada, R v Keegstra (1990) 3 SCR 697, (December 13, 1990)

- I’m working on a screenplay of Fahrenheit 451 that will star Mel Gibson. It will be better than the original because they left a lot of things out of the first film. … It works even better because we have political correctness now. Political correctness is the real enemy these days. The black groups want to control our thinking and you can't say certain things. The homosexual groups don't want you to criticize them. It's thought control and freedom of speech control.

- Ray Bradbury, as quoted in "Bradbury Talk Likely to Feature the Unexpected" by Anne Gasior, Dayton Daily News (1 October 1994), City Edition, Lifestyle/Weekendlife Section, p. 1; republished in Conversations with Ray Bradbury (2003) by Steven Louis Aggelis (PDF), p. 104

- I rise today to support the efforts of citizens everywhere to protect free speech on the Internet. Today, the Supreme Court heard arguments to determine the constitutionality of the Communications Decency Act [CDA], which criminalizes certain speech on the Internet. It is because of the hard work and dedication to free speech by netizens everywhere that this issue has gained the attention of the public, and now, our Nation's highest court. I have maintained from the very beginning that the CDA is unconstitutional, and I eagerly await the Supreme Court's decision on this case.

- One question that remains is at what point an individual Net poster has the right to assume prerogatives that have traditionally been only the province of journalists and news-gathering organizations. When the Pentagon Papers landed on the doorstep of the New York Times, the newspaper was able to publish under the First Amendment's guarantees of freedom of speech, and to make a strong argument in court that publication was in the public interest. … the amplification inherent in the combination of the Net's high-speed communications and the size of the available population has greatly changed the balance of power.

- Wendy M. Grossman (1997). Net.wars. New York University Press. p. 90. ISBN 0814731031.

- Freedom of speech is central to most every other right that we hold dear in the United States and serves to strengthen the democracy of our great country. It is unfortunate, then, when actions occur that might be interpreted as contrary to this honored tenet.

- Sam Farr, Congressional Record, "Freedom of Speech, Freedom of the Press", (November 7, 1997).

- Nobody deserves to be hurt, especially not for an idea.

- Kreshia Thomas, a black teenager who put herself in harm's way to protect a white man wearing Nazi tattoos and Confederate flag clothing from being beaten and kicked by an angry mob that thought he supported the racist Ku Klux Klan Wynne, Catherine (2013). The teenager who saved a man with an SS tattoo. British Broadcasting Corporation.

2000s

edit- Money is property; it is not speech. Speech has the power to inspire volunteers to perform a multitude of tasks on a campaign trail, on a battleground, or even on a football field. Money, meanwhile, has the power to pay hired laborers to perform the same tasks. It does not follow, however, that the First Amendment provides the same measure of protection to the use of money to accomplish such goals as it provides to the use of ideas to achieve the same results.

- John Paul Stevens, Concurring, Nixon v. Shrink Missouri Government PAC, 528 U.S. 377 (2000).

- A law imposing criminal penalties on protected speech is a stark example of speech suppression.

- First Amendment freedoms are most in danger when the government seeks to control thought or to justify its laws for that impermissible end. The right to think is the beginning of freedom, and speech must be protected from the government because speech is the beginning of thought.

- Anthony Kennedy, (Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition, 2002).

- The Government may not suppress lawful speech as the means to suppress unlawful speech.

- Anthony Kennedy, (Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition, 2002).

- Dissents speak to a future age. It's not simply to say, 'My colleagues are wrong and I would do it this way.' But the greatest dissents do become court opinions and gradually over time their views become the dominant view. So that's the dissenter's hope: that they are writing not for today but for tomorrow.

- Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, Interview with Nina Totenberg of National Public Radio (May 2, 2002).

- ... while there's no 'fair use' exception when it comes to trade secrets, anyone who discovers a trade secret without violating a confidentiality agreement can disseminate it freely. For example, if you board a commuter train in Atlanta and discover that a Coca-Cola employee has left the secret formula for the company's flagship product on one of the seats, you have no obligation not to reveal it to the world. More important, this means that newspapers often may legally publish material that may have been obtained illegally, as long as they did not induce the illegal taking or know about it beforehand and as long as no one was induced or solicited by the newspaper to steal the material in question.

- Although the freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment may benefit society generally, or communities in particular, we don't condition those freedoms on whether how we use them benefits anyone. There is no legal or constitutional requirement that each individual use these freedoms wisely. That is part of what it means to live in an open society: you get to make your own choice about whether to acquire wisdom. We don't let government choose for us.

- Mike Godwin (2003). Cyber Rights: Defending Free Speech in the Digital Age. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. p. 16. ISBN 0812928342.

- Among the principles in place that have seemed to work for us are individual freedom of expression (especially for those whose expression offends us) and a strong individual guarantee of privacy in our First Amendment-protected communications.

- Mike Godwin (2003). Cyber Rights: Defending Free Speech in the Digital Age. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. p. 16. ISBN 0812928342.

- In short, individual freedom of speech leads to a stronger society. But knowing that principle is not enough. You have to know how to put it to use on the Net.

- Mike Godwin (2003). Cyber Rights: Defending Free Speech in the Digital Age. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. p. 17. ISBN 0812928342.

- Exploring and understanding the Net is an ongoing process. Cyberspace never sits still; it evolves as fast as society itself. Only if we fight to preserve our freedom of speech on the Net will we ensure our ability to keep up with both the Net and society.

- Mike Godwin (2003). Cyber Rights: Defending Free Speech in the Digital Age. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. p. 19. ISBN 0812928342.

- Proponents of using government authority to censor certain undesirable images and comments on the airwaves resort to the claim that the airways belong to all the people, and therefore it's the government's responsibility to protect them. The mistake of never having privatized the radio and TV airwaves does not justify ignoring the first amendment mandate that "Congress shall make no law abridging freedom of speech." When everyone owns something, in reality nobody owns it. Control then occurs merely by the whims of the politicians in power. From the very start, licensing of radio and TV frequencies invited government censorship that is no less threatening than that found in totalitarian societies.

- Ron Paul, Congressional Record, "An Indecent Attack on the First Amendment", (March 10, 2004).

- What is freedom of expression? Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist.

- Imagine a world in which every single person on the planet is given free access to the sum of all human knowledge. That's what we're doing.

- Jimmy Wales, cited in — Slashdot readers' questions (July 28, 2004). "Wikipedia Founder Jimmy Wales Responds". Slashdot. Retrieved on 2008-01-04.

- While, legally and constitutionally, speech may be free, the space in which that freedom can be exercised has been snatched from us and auctioned to the highest bidders.

- Arundhati Roy, An Ordinary Person's Guide to Empire (2005), p. 48

- I am sure that as soon as speech was invented, efforts to suppress and control it began, and that process of suppression continues unabated.

- Gilbert S. Merritt, Jr., (Speech at the University of Oregon, 2004). — cited in: Gilbert S. Merritt, Speech at the University of Oregon, Nashville, TN: 2004. cited in — Merritt, Gilbert S. (2006). "The Lesson of Sullivan Has Been Forgotten". in Edelman, Rob. Freedom of the Press. Greenhaven Press. p. 75..

- Our Founding Fathers were the first to articulate the reasons for their First Amendment, the same reasons given by Learned Hand, and by Justice Brennan in New York Times v. Sullivan. It is a lesson we keep forgetting and must relearn in each succeeding generation.

- Gilbert S. Merritt, Jr., (Speech at the University of Oregon, 2004). — cited in: Gilbert S. Merritt, Speech at the University of Oregon, Nashville, TN: 2004. cited in — Merritt, Gilbert S. (2006). "The Lesson of Sullivan Has Been Forgotten". in Edelman, Rob. Freedom of the Press. Greenhaven Press. p. 75..

- New York Times v. Sullivan was about the suppression of speech in the South [during the 1960s]. Today's version of suppression is just another verse of the same song.

- Gilbert S. Merritt, Jr., (Speech at the University of Oregon, 2004). — cited in: Gilbert S. Merritt, Speech at the University of Oregon, Nashville, TN: 2004. cited in — Merritt, Gilbert S. (2006). "The Lesson of Sullivan Has Been Forgotten". in Edelman, Rob. Freedom of the Press. Greenhaven Press. p. 75..

- This "zeal for secrecy" I am talking about — and I have barely touched the surface — adds up to a victory for the terrorists. When they plunged those hijacked planes into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon three years ago this morning, they were out to hijack our Gross National Psychology. If they could fill our psyche with fear — as if the imagination of each one of us were Afghanistan and they were the Taliban — they could deprive us of the trust and confidence required for a free society to work. They could prevent us from ever again believing in a safe, decent or just world and from working to bring it about. By pillaging and plundering our peace of mind they could panic us into abandoning those unique freedoms — freedom of speech, freedom of the press — that constitute the ability of democracy to self-correct and turn the ship of state before it hits the iceberg.

- Bill Moyers, Speech to the Society of Professional Journalists (11 September 2004)

- Historically, of course, the Supreme Court really hasn't recognized that kind of reality. It hasn't tried to make distinctions among different kinds of press entities. And there may be strong reasons not to do this. First Amendment law is already very complicated. And if you're asking the Court now to superimpose a whole new set of distinctions on what has already become an unbearable number of complex distinctions, you may end up feeling sorry. There are lots and lots of different kinds of press entities and other speakers. And if each one gets its own First Amendment doctrine, that might be a world we don't want to live in.

- Elena Kagan, (Harvard Law Bulletin, 2005). — cited in: London, Robb (Spring 2005). "Faculty Viewpoints: Can Reporters Refuse to Testify?". Harvard Law Bulletin..

- Publishing on the Internet is different than importing and exporting books, magazines, and newspapers. The Internet is a new forum, and there is something unprecedented in the idea of simultaneous, low-cost publication available to readers around the world. Speakers reach listeners in many places where they never could have been heard before. Listeners have access to the speech of individuals who may have a freedom to publish that is unknown in the listener's own country. Speakers and listeners will lose these benefits if Internet speech regulation is left to the determination of the most restrictive states. We also lose these benefits if regulation is so unpredictable as to make Internet speech more risky than warranted by the potential rewards it offers.

- Samuel Peter Nelson (2005). Beyond the First Amendment: The Politics of Free Speech and Pluralism. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 166. OCLC 56924685.

- I am so disgusted with people who think free speech is defined as being able to say what you think without being criticized.

- Jonah Goldberg, "Dissident Chicks" (12 February 2007), The Corner, National Review

- In the national debate about a serious issue, it is the expression of the minority's viewpoint that most demands the protection of the First Amendment. Whatever the better policy may be, a full and frank discussion of the costs and benefits of the attempt to prohibit the use of marijuana is far wiser than suppression of speech because it is unpopular.

- A final argument for broad freedom of expression is its effect on the character of individuals in a society. Citizens in a free society must have courage — the courage to hear not only unwelcome political speech but novel and shocking ideas in science and the arts.

- Anthony Lewis (2007). Freedom for the Thought That We Hate; A Biography of the First Amendment. Basic Books. p. 186. ISBN 0465039170.

- Free speech does not empower us, and it does not equal freedom. Free speech is a privilege that can be — and is — taken away by the government when it serves their interests.

- Active liberty is particularly at risk when law restricts speech directly related to the shaping of public opinion, for example, speech that takes place in areas related to politics and policy-making by elected officials. That special risk justifies especially strong pro-speech judicial presumptions. It also justifies careful review whenever the speech in question seeks to shape public opinion, particularly if that opinion in turn will affect the political process and the kind of society in which we live.

- The Court said that the First Amendment forbids statutory effort to restrict information in order to help the public make wiser decisions.

- Stephen Breyer (2008). Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 51. ISBN 0-307-26313-4. OCLC 59280151..

- Traditional modern liberty — the individual's freedom from government restriction — remains important. Individuals need information freely to make decisions about their own lives. And, irrespective of context, a particular rule affecting speech might, in a particular instance, require individuals to act against conscience, inhibit public debate, threaten artistic expression, censor views in ways unrelated to a program's basic objectives, or create other risks of abuse. These possibilities themselves form the raw material out of which courts will create different presumptions applicable in different speech contexts. And even in the absence of presumptions, courts will examine individual instances with the possibilities of such harms in mind.

- Stephen Breyer (2008). Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 54. ISBN 0-307-26313-4. OCLC 59280151..

- Money is not speech, it is money. But the expenditure of money enables speech, and that expenditure is often necessary to communicate a message, particularly in a political context. A law that forbade the expenditure of money to communicate could effectively suppress the message.

- Stephen Breyer (2008). Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 46. ISBN 0-307-26313-4. OCLC 59280151..

- All speech should be presumed to be protected by the Constitution, and a heavy burden should be placed on those who would censor to demonstrate with relative certainty that the speech at issue, if not censored, would lead to irremediable and immediate serious harm.

- Alan Dershowitz (2008). Finding, Framing, and Hanging Jefferson: A Lost Letter, a Remarkable Discovery, and Freedom of Speech in an Age of Terrorism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 30. ISBN 0470450436.

- I care deeply about freedom of speech, but I am also a realist about terrorism and the threat it poses. I worry that among the first victims of another mass terrorist attack will be civil liberties, including freedom of speech. The right of every citizen to express dissident and controversial views remains a powerful force in my life. I not only believe in it, I practice it.

- Alan Dershowitz (2008). Finding, Framing, and Hanging Jefferson: A Lost Letter, a Remarkable Discovery, and Freedom of Speech in an Age of Terrorism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 37. ISBN 0470450436.

- Censorship laws are blunt instruments, not sharp scalpels. Once enacted, they are easily misapplied to merely unpopular or only marginally dangerous speech.

- Alan Dershowitz (2008). Finding, Framing, and Hanging Jefferson: A Lost Letter, a Remarkable Discovery, and Freedom of Speech in an Age of Terrorism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 191. ISBN 0470450436.

- Under our First Amendment, a censorship law would have to be written in broad general language and could not be directed at specific religious, ethnic, racial, or political groups. Any such law could be misused by politicians to censor their political enemies or other "undesirable" groups.

- Alan Dershowitz (2008). Finding, Framing, and Hanging Jefferson: A Lost Letter, a Remarkable Discovery, and Freedom of Speech in an Age of Terrorism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 191. ISBN 0470450436.

- Regardless of all of the ways that the media have changed in recent years, one thing that will never go out of style in America is the ability of a free press to keep the public accurately and honestly informed about its government.

- Candice Miller, "Detroit Free Press Wins Pulitzer Prize", Congressional Record, Volume 155, Number 59 (Wednesday, April 22, 2009), United States House of Representatives, Page H4588.

- As a conservative who believes in limited government, I believe the only check on government power in real time is a free and independent press. A free press ensures the flow of information to the public, and let me say, during a time when the role of government in our lives and in our enterprises seems to grow every day--both at home and abroad--ensuring the vitality of a free and independent press is more important than ever.

- Mike Pence, Congressional Record, "World Press Freedom Day", (May 4, 2009).

2010s

edit- We believe that a key part of combating extremism is preventing recruitment by disrupting the underlying ideologies that drive people to commit acts of violence. That's why we support a variety of counterspeech efforts.

- Monika Bickert, Facebook's head of global policy management, as reported by CNBC, January 17, 2018

- Countries that censor news and information must recognize that from an economic standpoint, there is no distinction between censoring political speech and commercial speech. If businesses in your nations are denied access to either type of information, it will inevitably impact on growth.

- Hillary Rodham Clinton, United States Department of State ("Secretary of State Clinton on Internet Freedom", Office of the Spokesman, January 21, 2010).

- America is well on its way to making it illegal to say anything nasty about gays, Jews, blacks and women. “Hate speech,” far short of any direct incitement to violence, is on the edge of being criminalized, with the First Amendment gone the way of the dodo.

- Alexander Cockburn, "The Hate Crimes Bill: How Not to Remember Matthew Shepard", Counterpunch.org, June 26–28, 2010.

- Speech is an essential mechanism of democracy, for it is the means to hold officials accountable to the people. [...] The right of citizens to inquire, to hear, to speak, and to use information to reach consensus is a precondition to enlightened self-government and a necessary means to protect it. [...] By taking the right to speak from some and giving it to others, the Government deprives the disadvantaged person or class of the right to use speech to strive to establish worth, standing, and respect for the speaker’s voice. The Government may not by these means deprive the public of the right and privilege to determine for itself what speech and speakers are worthy of consideration. The First Amendment protects speech and speaker, and the ideas that flow from each.

- Anthony Kennedy, Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 310 (2010) (Opinion of the Court).

- When Government seeks to use its full power, including the criminal law, to command where a person may get his or her information or what distrusted source he or she may not hear, it uses censorship to control thought. This is unlawful.

- Anthony Kennedy, Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 310 (2010) (Opinion of the Court).

- Free speech is the bedrock of liberty and a free society. And yes, it includes the right to blaspheme and offend.

- Ayaan Hirsi Ali (2010). Nomad: From Islam to America. Knopf Canada. p. 215. ISBN 0307398501.

- Every important freedom that Western individuals possess rests on free expression. We observe what is wrong, and we say what is wrong, in order that it may be corrected. This is the message of the Enlightenment, the rational process that developed today's Western values: Go. Inquire. Ask. Find out. Dare to know. Don't be afraid of what you'll find. Knowledge is better than superstition, blind belief, and dogma. If you cannot voice — or even consider — criticism, then you will never see what is wrong. You cannot solve a problem unless you identify its source.

- Ayaan Hirsi Ali (2010). Nomad: From Islam to America. Knopf Canada. p. 214. ISBN 0307398501.

- The west has fiscalised its basic power relationships through a web of contracts, loans, shareholdings, bank holdings and so on. In such an environment it is easy for speech to be "free" because a change in political will rarely leads to any change in these basic instruments. Western speech, as something that rarely has any effect on power, is, like badgers and birds, free.

- Julian Assange, cited in — "Julian Assange answers your questions". The Guardian. December 3, 2010. Retrieved on October 23, 2012.

- Free speech is meaningless if the commercial cacophony has risen to the point where no one can hear you.

- Naomi Klein, No Logo, 10th anniversary edition (2009: Vintage Canada, an imprint of Random House of Canada, Ltd.), ISBN 978-0-307-39909-0, p. 284. Previously published under the title No Logo: Taking aim at the brand bullies (2000: Vintage Canada), ISBN 0-676-97282-9, p. 284.