Bolsheviks

faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party; a major faction in the Russian Civil War

(Redirected from Bolshevist)

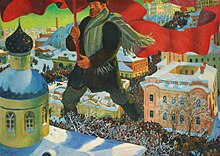

The Bolsheviks, also known in English as the Bolshevists, were a faction founded by Vladimir Lenin and Alexander Bogdanov that split from the Menshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). The faction eventually becoming the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Their beliefs and practices were often referred to as Bolshevism.

Quotes

edit- This position by the Leninists of the necessity for a dictatorship to protect the revolution was not proven in the Civil War which followed the Russian revolution; in fact without support of the Anarchists and other left-wing forces, along with the Russian people, the Bolshevik government would have been defeated. And then true to any dictatorship, it turned around and wiped out the Russian and Ukrainian Anarchist movements, along with their left-wing opponents like the Mensheviks and Social revolutionaries. Even ideological opponents in the Bolshevik party were imprisoned and put to death. Lenin and Trotsky killed millions of Russian citizens right after the Civil War, when they were consolidating State power, which preceded Stalin’s bloody rule. The lesson is that we should not be tricked into surrendering the grassroots people’s power to dictators who pose as our friends or leaders.

- The Provisional Government that took the Tsar's place aimed to establish a republic with a liberal constitution and parliamentary institutions. Its prospects were far from bad. However, the determination of its leaders to keep the war going and to postpone decisions on the burning question of land reform until after a Constituent Assembly had been elected created a window of opportunity for more extreme elements. The Bolsheviks had in fact been taken by surprise by the revolution. 'It's staggering!' exclaimed Lenin when he heard the news in Zurich. 'Such a surprise! Just imagine! We must get home, but how?' The German High Command answered that question, providing him not only with a railway ticket to Petrograd but also, through two shady intermediaries named Parvus and Ganetsky, with funds to subvert the new government. Instead of having him and his associates arrested, as they richly deserved to be, the Provisional Government dithered. On August 27, egged on by conservative critics of the new regime, the Supreme Commander of the Russian Army, General Lavr Kornilov, launched an abortive military coup. The unintended effect was to boost support for the Bolsheviks within the soviets, which had sprung up as a kind of parallel government not only in Petrograd (as in 1905) but in other cities too. Two months later, on October 24, 1917, the Bolsheviks staged a coup d'état of their own. At the time, it did not seem like a world-shaking event. Indeed, more people were hurt in Sergei Eisenstein's subsequent reenactment for his film October. Hardly anyone expected the new regime to last.

- Niall Ferguson, The War of the World: Twentieth-Century Conflict and the Descent of the West (2006), p. 143

- The Bolsheviks promised their supporters 'Peace, Bread and Power to the Soviets'. Peace turned out to mean abject capitulation. At Brest-Litovsk, in the sprawling brick fortress that guards the River Bug, the German High Command demanded sweeping cessions of territory from a motley Bolshevik delegation (to keep up revolutionary appearances, a token peasant named Roman Stashkov had been picked up en route). Trotsky, who was in charge of Bolshevik foreign policy during the negotiations, played for time, defiantly if somewhat opaquely proclaiming 'neither peace nor war'. His hope was that if the negotiations could be spun out for long enough, world revolution might supervene. The Germans simply advanced into the Baltic provinces, Poland and the Ukraine. There was almost no resistance from the demoralized Russian forces. Indeed, for a moment it seemed as if the Germans might even take Petrograd, and the Bolshevik leadership was forced hastily to remove themselves to Moscow, henceforth their capital. When Trotsky finally yielded to Lenin's argument for capitulation - after stormy debates that led the Left Socialist Revolutionaries to quit the revolutionary government - the Bolsheviks had to sign away a third of the pre-war Russian Empire's agricultural land and population, more than half of her industry and nearly 90 per cent of her coalmines. Poland, Finland, Lithuania and the Ukraine became independent, though under German tutelage. The war in the East was the war the Germans won. The money they had used to send Lenin back to Russia had, it seemed, paid a handsome return. Yet the Russian Revolution proved to be not the end of the war, merely its mutation. After Germany's eastern triumph was rendered null and void by her defeat in the West, the war in the East changed into a terrible civil war, in many ways as costly in human life as the conventional war between empires that preceded it.

- Niall Ferguson, The War of the World: Twentieth-Century Conflict and the Descent of the West (2006), pp. 143-144

- The other epidemic was Bolshevism, which for a time seemed almost as contagious and ultimately proved as lethal as the influenza. With the end of the war, Soviet-style governments were proclaimed in Budapest, Munich and Hamburg. The red flag was even raised above Glasgow City Chambers. Lenin dreamed of a 'Union of Soviet Republics of Europe and Asia'. Trotsky declared that 'the road to Paris and London lies via the towns of Afghanistan, the Punjab and Bengal'. Even distant Buenos Aires was rocked by strikes and street fighting.

- Niall Ferguson, The War of the World: Twentieth-Century Conflict and the Descent of the West (2006), pp. 143-144

- The Revolution had been made in the name of peace, bread and Soviet power. It turned out to mean civil war, starvation and the dictatorship of the Bolshevik Party's Central Committee and its increasingly potent subcommittee, the Politburo. Workers who had supported the Bolsheviks in the expectation of a decentralized soviet regime found themselves being gunned down if they had the temerity to strike at newly nationalized factories. With inflation rampant, their wages in real terms were just a fraction of what they had been before the war. 'War Communism' reduced hungry city dwellers to desperate bartering expeditions to the country and to burning everything from their neighbours' doors to their own books for heat. As the conscription system grew more effective, more and more young men found themselves drafted into the Red Army, which grew in number from less than a million in January 1919 to five million by October 1920, though desertion rates remained high, especially around harvest time. When the previously pro-Bolshevik sailors of Kronstadt mutinied in February 1921 , they denounced the regime for crushing freedom of speech, press and assembly and filling prisons and concentration camps with their political rivals.

- Niall Ferguson, The War of the World: Twentieth-Century Conflict and the Descent of the West (2006), pp. 152-153

- First of all, we have to understand what communism is. I mean, to me, real communism, the Soviet communism, is basically a mask for Bolshevism, which is a mask for Judaism.

- Robert Fischer, Press Conference, September 1 1992 [1]

- The depravity of the Tcheka was a matter of common knowledge. People were shot for slight offences, while those who could afford to give bribes were freed even after they had been sentenced to death.

- Bolshevism, which once aspired to supplant tottering capitalism, is now in a state of incurable degeneration both at home in Russia and internationally.

- Lucien Laurat, Marxism and Democracy, 1940, published by the Left Book Club, Victor Gollancz Ltd, London; translated by Edward Fitzgerald. Text online at the Marxists Internet Archive.

- The celebrated phrase, 'so much the worse for the facts', would satisfy only the high priests of Marxism, for Marxism also has its high priests, and these priests, like all others, daily deny the principles they claim to defend. Bolshevism is a living proof of this.

- Lucien Laurat, Marxism and Democracy, 1940, published by the Left Book Club, Victor Gollancz Ltd, London; translated by Edward Fitzgerald. Text online at the Marxists Internet Archive.

- The origin of Bolshevism is inseparably linked with the struggle of what is known as Economism (opportunism which rejected the political struggle of the working class and denied the latter’s leading role) against revolutionary Social-Democracy in 1897–1902.

- Vladimir Lenin, On Bolshevism, 1913, published in Among Books, Vol. II, Second Ed; translated by Stepan Apresyan. Text online at the Marxists Internet Archive.

- It is needless to rehearse the utter and degrading loss of individual liberty which results from the orthodox communistic theory that society is itself an organism in which each person is merely an insignificant cell. It is not in anti-Soviet libels, but in the proud reports of Soviet leaders, that we read of the forcible transfer of whole village populations from their ancestral abodes to new locations in the Arctic, and of the arbitrary ordering of Moscow clerks to tasks of manual labour in the farms and forests of Siberia. All these things are logical outgrowths of what the Bolsheviks call their “collectivistic ideology”, and typical examples of the horrors which might fall upon us if communism were to gain a foothold here.

- H. P. Lovecraft, "Some Repetitions on the Times" (1933). Reprinted in S. T. Joshi, ed., Miscellaneous Writings (Arkham House, 1995)

- It is a curious fact that the Russian Bolsheviks, in carrying by compulsion mass conceptions to their utmost extreme, seem to have lost not only the guidance of great personalities, but even the economic fertility of the process itself. The Communist theme aims at universal standardization. The individual becomes a function: the community is alone of interest: mass thoughts dictated and propagated by the rulers are the only thoughts deemed respectable. No one is to think of himself as an immortal spirit, clothed in the flesh, but sovereign, unique, indestructible. No one is to think of himself even as that harmonious integrity of mind, soul and body, which, take it as you will, may claim to be the Lord of Creation. Subhuman goals and ideals are set before these Asiastic millions. The Beehive? No, for there must be no queen and no honey, or at least no honey for others. In Soviet Russia we have a society which seeks to model itself upon the Ant. There is not one single social or economic principle or concept in the philosophy of the Russian Bolshevik which has not been realized, carried into action, and enshrined in immutable laws a million years ago by the White Ant.

- Winston Churchill, Mass Effects in Modern Life, 1 December 1925

- Throughout the history of the socialist movement there has, therefore, been a strand of feminist critique from within. Many feminists shared in the vision of a just society, but criticised the ways in which communist parties sought to bring it about. Amongst the Bolsheviks, Inessa Armand and Alexandra Kollontai were early critics of their party's policies and practice, and they, along with anarchist feminists such as Emma Goldman, laid some of the early groundwork in identifying socialism's failures.

- Maxine Molyneux Women's Movements in International Perspective: Latin America and Beyond (2000)

- Viewing the Bolsheviks’ power seizure from the perspective of history, one can only marvel at their audacity. None of the leading Bolsheviks had experience in administering anything, and yet they were about to assume responsibility for governing the world’s largest country. Nor, lacking business experience, did they shy from promptly nationalizing and hence assuming responsibility for managing the world’s fifth-largest economy. They saw in the overwhelming majority of Russia’s citizens—the bourgeoisie and the landowners as a matter of principle and most of the peasantry and intelligentsia as a matter of fact—class enemies of the industrial workers, whom they claimed to represent. These workers constituted a small proportion of Russia’s population—at best 1 or 2 percent—and of this minority only a minuscule number followed the Bolsheviks: on the eve of the November coup, only 5.3 percent of industrial workers belonged to the Bolshevik party. This meant that the new regime had no alternative but to turn into a dictatorship—a dictatorship not of the proletariat but over the proletariat and all the other classes. The dictatorship, which in time evolved into a totalitarian regime, was thus necessitated by the very nature of the Bolshevik takeover. As long as they wanted to stay in power, the Communists had to rule despotically and violently; they could never afford to relax their authority. The principle held true of every Communist regime that followed.

- Richard Pipes, Communism: A History (2003)

- For two decades the supporters of Bolshevism have been hammering it into the masses that dictatorship is a vital necessity for the defense of the so-called proletarian interests against the assaults of counter-revolution and for paving the way for Socialism. They have not advanced the cause of Socialism by this propaganda, but have merely smoothed the way for Fascism in Italy, Germany and Austria by causing millions of people to forget that dictatorship, the most extreme form of tyranny, can never lead to social liberation. In Russia, the so-called dictatorship of the proletariat has not led to Socialism, but to the domination of a new bureaucracy over the proletariat and the whole people. … What the Russian autocrats and their supporters fear most is that the success of libertarian Socialism in Spain might prove to their blind followers that the much vaunted "necessity of dictatorship" is nothing but one vast fraud which in Russia has led to the despotism of Stalin and is to serve today in Spain to help the counter-revolution to a victory over the revolution of the workers and the peasants.

- Rudolf Rocker, The Tragedy of Spain (1937), p. 35.

- The hopes which inspire communism are, in the main, as admirable as those instilled by the Sermon on the Mount, but they are held as fanatically and are as likely to do as much harm.

- Bertrand Russell, The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism (1920), Part I, The Present Condition of Russia, Ch. 1: What Is Hoped From Bolshevism.

- The Bolsheviks had first to perform the constructive work of capitalism before they could really begin the transformative work of socialism. As the state created industry, they decided, it would draw members of the Soviet Union’s countless cultures into a larger political loyalty that would transcend any national difference. The mastery of both peasants and nations was a grand ambition indeed, and the Bolsheviks concealed its major implication: that they were the enemies of their own peoples, whether defined by class or by nation. They believed that the society that they governed was historically defunct, a bookmark to be removed before a page was turned. To consolidate their power when the war was over, and to gain loyal cadres for the economic revolution to come, the Bolsheviks had to make some compromises. Nations under their control would not be allowed independent statehood, of course, but nor were they condemned to oblivion. Though Marxists generally thought that the appeal of nationalism would decline with modernization, the Bolsheviks decided to recruit the nations, or at least their elites, to their own campaign to industrialize the Soviet Union. Lenin endorsed the national identity of the non-Russian peoples. The Soviet Union was an apparent federation of Russia with neighboring nations. Policies of preferential education and hiring were to gain the loyalty and trust of non-Russians. Themselves subjects of one and then rulers of another multinational state, the Bolsheviks were capable of subtle reasoning and tact on the national question. The leading revolutionaries themselves were far from being Russians in any simple way. Lenin, regarded and remembered as Russian, was also of Swedish, German, Jewish, and Kalmyk background; Trotsky was Jewish, and Stalin was Georgian.

- Timothy D. Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books, 2010

- The Bolsheviks presented history as a struggle of classes, the poorer making revolutions against the richer to move history forward. Thus, officially, the plan to annihilate the kulaks was not a simple decision of a rising tyrant and his loyal retinue; it was a historical necessity, a gift from the hand of a stern but benevolent Clio. The naked attack of organs of state power upon a category of people who had committed no crime was furthered by vulgar propaganda. One poster—under the title “We will destroy the kulaks as a class!”—portrayed a kulak under the wheels of a tractor, a second kulak as an ape hoarding grain, and a third sucking milk directly from a cow’s teat. These people were inhuman, they were beasts—so went the message. In practice, the state decided who was a kulak and who was not. The police were to deport prosperous farmers, who had the most to lose from collectivization. In January 1930 the politburo authorized the state police to screen the peasant population of the entire Soviet Union. The corresponding OGPU order of 2 February specified the measures needed for “the liquidation of the kulaks as a class.” In each locality, a group of three people, or “troika,” would decide the fate of the peasants. The troika, composed of a member of the state police, a local party leader, and a state procurator, had the authority to issue rapid and severe verdicts (death, exile) without the right to appeal. Local party members would often make recommendations: “At the plenums of the village soviet,” one local party leader said, “we create kulaks as we see fit.” Although the Soviet Union had laws and courts, these were now ignored in favor of the simple decision of three individuals. Some thirty thousand Soviet citizens would be executed after sentencing by troikas.

- Timothy D. Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books, 2010

- The Bolshevik policy of terror was more systematic, better organized, and targeted at whole social classes. Moreover, it had been thought out and put into practice before the outbreak of the civil war. The White Terror was never systematized in such a fashion. It was almost invariably the work of detachments that were out of control, and taking measures not officially authorized by the military command that was attempting, without much success, to act as a government. If one discounts the pogroms, which Denikin himself condemned, the White Terror most often was a series of reprisals by the police acting as a sort of military counterespionage force. The Cheka and the Troops for the Internal Defense of the Republic were a structured and powerful instrument of repression of a completely different order, which had support at the highest level from the Bolshevik regime.

- Nicolas Werth, The Black Book of Communism, p 82

- The real forces behind Bolshevism in Russia are Jewish forces, and Bolshevism is really an instrument in the hands of the Jews for the establishment of their future Messianic kingdom.

- Father Denis Fahey, The Rulers of Russia, p. 25

- The Bolsheviks shared with the elites within the Russian empire a conviction that their country would eventually become the center of a new world civilization that would be both modern and just. Lenin believed that having been the first country that experienced a socialist revolution, Russia could do much to help revolutionaries in other countries – it could function as a base area and rear guard for the revolutions in the more advanced countries of Europe, which, Lenin believed, would follow soon. But in spite of the country’s social and technological backwardness, Lenin believed that the organization of its proletariat through the Communist Party had given Russia the edge – and that it could teach the lessons of the October Revolution to other proletarian parties. ‘‘To wait until the working classes carry out a revolution on an international scale means that everyone will remain suspended in mid-air,’’ Lenin said in May 1918. The very fact that the main imperialist powers had intervened against the new Soviet state in the civil war that followed the October Revolution proved to the Bolsheviks how crucial their section of the front against imperialism was.

- Odd Arne Westad, The Global Cold War: Third World Intervention and the Making of Our Times (2012), p. 51

- The Communist challenge to the capitalist world system also started with the Great War. The war split Social Democratic parties everywhere into prowar and antiwar camps. Some Social Democrats supported the war efforts out of a sense of obligation to the nation. But in Germany, France, Italy, and Russia, minority socialists, including the Russian Bolsheviks, condemned the fighting as a conflict between different groups of capitalists. Karl Liebknecht, the only socialist who voted against the war in the German parliament, bravely argued that “this war, which none of the peoples involved desired, was not started for the benefit of the German or of any other people. It is an imperialist war, a war for capitalist domination of world markets and for the political domination of important colonies in the interest of industrial and financial capital.” Revolutionaries such as Liebknecht and Lenin contended that soldiers, workers, and peasants had more in common with their brothers on the other side than with their superior officers and the capitalists behind the lines. The war was between robbers and thieves, for which ordinary people had to suffer. Capitalism itself produced war and would produce more wars if it was not abolished. The answer, the ultra-Left proclaimed, was a transnational form of revolution, in which soldiers turned their weapons on their own officers and embraced their comrades across the trenches.

- Odd Arne Westad, The Cold War: A World History (2017)