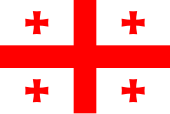

Georgia (country)

country in the Caucasus

Georgia is a country in Europe. It is bounded to the west by the Black Sea, to the north by Russia, to the south by Turkey and Armenia, and to the southeast by Azerbaijan. The capital and largest city is Tbilisi. Georgia covers a territory of 69,700 square kilometers (26,911 sq mi), and its 2017 population is about 3.718 million. The sovereign state of Georgia is a unitary semi-presidential republic, with the government elected through a representative democracy.

Quotes

editB

edit- By mid-1921, the Red Army had overcome opposition in the Caucasus and Central Asia, although its invasion of Poland in 1920 was driven back. These conflicts were linked to rivalry between the great powers. The conflict in the Caucasus was in part an instance of the struggle between Britain and the Soviet Union. The British saw Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia, each of which briefly became independent in the Russian Civil War, as a buffer for their interests in Iraq, Persia (Iran) and India; and as a source of raw materials, notably oil from Azerbaijan and access to oil from Georgia. In late 1918, the British landed troops in the Black Sea port of Batumi, the terminus of the railway to the oil-producing centre of Baku on the Caspian Sea. This was a commitment advocated by Mackinder. Torpedo-armed coastal motor boats were sent overland to the Caspian Sea. However, under pressure from too many commitments, the British withdrew their forces from late 1919. Benefiting from the divisions between the Caucasus republics, the Soviets advanced and took them over in 1920–1.

- Jeremy Black, The Cold War: A Military History (2015)

- While separatist nationalisms developed and were increasingly expressed, there was no protracted attempt to use the extensive military resources of the Soviet state to prevent the collapse of the Soviet Union. Already, in 1986–7, the government had refused to employ force to support party leaders in the Baltic Republics. When the crisis rose to a height, counterreform attempts by the Soviet military, keen to preserve the integrity of the state, led to action against nationalists in Georgia (1989), Azerbaijan (1990), Lithuania (1991), Latvia (1991), and Moldova (1992). However, these steps were small-scale, and there was no significant violent supporting action by the 25 million Russians living within the Soviet Union but outside Russia, those, for example, who played a key role in crises in Crimea and eastern Ukraine in 2014.

- Jeremy Black, The Cold War: A Military History (2015)

- You are building a democratic society where the rights of minorities are respected, where a free press flourishes, a vigorous opposition is welcome, and unity is achieved through peace... In this new Georgia, the rule of law will prevail, and freedom will be the birthright of every citizen... [T]he sovereignty and territorial integrity of Georgia must be respected... As you build freedom in this country, you must know that the seeds of liberty you are planting in Georgian soil are flowering across the globe.

- George W. Bush, as quoted in "President Addresses and Thanks Citizens in Tbilisi, Georgia" (10 May 2005), Office of the Press Secretary

G

edit- The Georgian Republic aspires to its worthy place in the world's community of states; it affirms and equally guarantees, as envisioned by international law, all the fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual, of nations, ethnic, religious, and linguistic groups as demanded by the rules of the United Nations...

- Zviad Gamsakhurdia, as quoted in Georgia: A Political History Since Independence (2013), by Stephen Jones, I.B. Tauris, p. xxi

J

edit- In 2004 the Baltic states, Bulgaria and Romania formally joined NATO, as did Slovakia and Slovenia. Soon afterwards, the American president, George W. Bush (2001–9), openly mooted Ukraine and Georgia also joining, which would advance NATO to Russia’s southern frontier. Both Germany and France challenged the wisdom of such blatant provocation. Putin repeated Yeltsin’s warning that any NATO advance to the frontier ‘would be taken in Russia as a direct threat to the security of our country’. In the summer of 2008 he reacted by invading Georgia’s Russian-speaking northern provinces of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Europe’s only response was for France’s president, Nicolas Sarkozy, to negotiate a ceasefire.

- Simon Jenkins, A Short History of Europe: From Pericles to Putin (2018)

- Georgians have a proverb: "custom is stronger than faith". It reflects Georgians' belief that the past is always trumps.

- Stephen F. Jones, Georgia: A Political History Since Independence (2013), I.B. Tauris, p. 8

- Soviet colonialism sabotaged the foundations of a modern, liberal national state in Georgia.

- Stephen F. Jones, Georgia: A Political History Since Independence (2013), I.B. Tauris, p. 16

N

edit- Around the same time, communism in Central and Eastern Europe finally fell, but its economic rivalry with capitalism had, of course, long since been decided. It’s easy to think that these countries were never close to the market economies, but in 1950 countries such as the Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary had a GDP per capita about a quarter higher than poor Western countries such as Spain, Portugal and Greece. In 1989, the eastern states were nowhere close. The eastern part of Germany was richer than West Germany before World War II. When the Berlin Wall fell on 9 November 1989, East Germany’s GDP per capita was not even half that of West Germany’s. Of these countries, those that liberalized the most have on average developed the fastest and established the strongest democracies. An analysis of twenty-six post-communist countries showed that a 10 per cent increase in economic freedom was associated with a 2.7 per cent faster annual growth. Political and economic institutions have improved the most in the Central and Eastern European countries that are now members of the EU, not least the Baltic countries, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Today, they are some of the freest countries in the world and have more than tripled average incomes since independence. But one can also observe a recent reformer like Georgia. It was seen as an economic basket case, but after the Rose Revolution in 2003 it increased per capita incomes almost threefold and cut extreme poverty rates by almost two-thirds.

- Johan Norberg, The Capitalist Manifesto: Why the Global Free Market Will Save the World (2023)

P

edit- Praise be to the heavenly bestower of Blessings, praise be to paradise on earth, to the radiant Iberia. Praise be to brotherhood and to unity, praise be to liberty, praise be to the everlasting, lively Georgian people!

- Kote Potskhverashvili, "Dideba" (1918)

S

edit- Georgia is the country of unique culture. We are not only old Europeans, we are the very first Europeans, and therefore Georgia holds special place in European civilization. Georgia should serve as a paragon for democracy where all citizens are equal before the law, where every citizen will have an equal opportunity for the pursuit of success and realization of his or her possibilities. Georgia should become and will become a homeland for independent, educated and proud people.

- Mikheil Saakashvili, inaugural address (25 January 2004)

- Also quoted as: "Georgia is not just a European country, but one of the most ancient European countries." in A World of Curiosities: Surprising, Interesting, and Downright Unbelievable (2012), by John Oldale, p. 274

- It is time we Georgians did not depend only on others, it is time we asked what Georgia will do for the world... Our steady course is towards European integration. It is time Europe finally saw and valued Georgia and took steps towards us.

- Mikheil Saakashvili, as quoted in "Georgia swears in new president" (25 January 2004), BBC News

- Standing at David's tomb, we must say Georgia will unite, Georgia will become strong and will restore its integrity... I want all of us to do it together and I promise not to become a source of shame for you.

- Mikheil Saakashvili, as quoted in "Georgia swears in new president" (25 January 2004), BBC News

- Georgia does not need Russia as an enemy.

- Mikheil Saakashvili, as quoted in "EU integration a key aim of Saakashvili" (26 January 2004), Irish Times

- [W]hen the people of Georgia rose up to defend their freedom - they also rose up to reclaim their future. A future that would no longer be defined by the false promises, wholesale decay, and state disintegration of the recent past. A future no longer dominated by the politics of division, state-sanctioned theft and disregard for the poorest parts of society.

- Mikheil Saakashvili, as quoted in "Remarks of the President of Georgia H.E. Mikheil Saakashvili to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe" (26 January 2005), ReliefWeb

- Georgia's character - now and forever - celebrates tolerance, embraces diversity, relishes lively and open debate, and above all, respects liberty and human dignity. Georgia is a democracy, because above all - its national identity is rooted in the traditions of democracy.

- Mikheil Saakashvili, as quoted in "Remarks of the President of Georgia H.E. Mikheil Saakashvili to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe" (26 January 2005), ReliefWeb

- For the first time in 15 years, Georgia this winter has its electric power guaranteed without deficit. This is a historic achievement.

- Mikheil Saakashvili, as quoted in "Ebullience in Georgia replaced by energy crisis" (29 January 2006), by Mike Eckel, Deseret News

- A united Georgia needs our unity now, to work together towards our many common goals.

- Mikheil Saakashvili, inaugural address (21 January 2008)

- Well, killing me makes no sense because Georgia already has a Western-educated political class.

- Mikheil Saakashvili, as quoted in "An American Friend" (19 October 2008), The New York Times

- We must create the Georgia that our ancestors dreamed of, the Georgia that we dream of.

- Mikheil Saakashvili, as quoted in "Selling the Georgian Dream" (23 November 2012), by Luka Oreskovic, The Moscow Times

- There was a hierarchy of material conditions in the communist world. The Yugoslavs, with the closest commercial links with the West, did best in the range and quality of goods available. Next came the East Germans, followed by the Hungarians and the Poles. Citizens of the USSR trailed in after them; and, still more galling to Russian national pride, the Georgians and Estonians in the Soviet Union enjoyed better conditions than those available to the Russians. The stereotypical Georgian, in the Russian popular imagination, was a swarthy ‘Oriental’ who smuggled oranges in large suitcases from his collective farm to the large cities of the RSFSR. That fruit could be an item of internal contraband speaks volumes about communism’s economic inefficiency.

- Robert Service, Comrades: A History of World Communism (2009)

W

edit- Georgia's transformation since 2003 has been remarkable... The lights are on, the streets are safe, and public services are corruption-free.

- World Bank, as quoted in "Georgia: Saakashvili The Corruption Slayer" (2 February 2012), by Adam Cardais, Transitions Online: Regional Intelligence, East of Center

Z

edit- It is not by mere chance that we [Georgians] have adopted two very important ideas as our watch words: freedom and responsibility.

- Zurab Zhvania, as quoted in "President Addresses and Thanks Citizens in Tbilisi, Georgia" (10 May 2005), Office of the Press Secretary

External links

edit- Encyclopedic article on Georgia (country) on Wikipedia