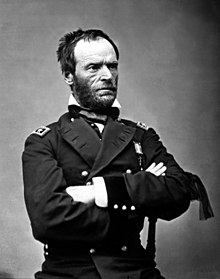

William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman (8 February 1820 – 14 February 1891) was a United States Army general during the American Civil War. He succeeded General Ulysses S. Grant as commander of the Western Theater of that war in the spring of 1864. He later served as Commanding General of the U.S. Army from 1869 to 1883. He is best known for his "March to the Sea" through the U.S. state of Georgia that destroyed a large amount of Confederate infrastructure and appropriated supplies from Confederate civillians while operating without supply lines from the north. He is widely regarded by historians as an early advocate of "Total War".

Quotes edit

1860s edit

- Still on the whole the campaign is the best, cleanest and most satisfactory of the war. I have received the most fulsome praise of all men from the President down, but I fear the world will jump to the wrong conclusion that because I am in Atlanta the work is done. Far from it. We must kill three hundred thousand I have told of so often, and the further they run the harder for us to get them.

1860 edit

0* You people of the South don't know what you are doing. This country will be drenched in blood, and God only knows how it will end. It is all folly, madness, a crime against civilization! You people speak so lightly of war; you don't know what you're talking about. War is a terrible thing! You mistake, too, the people of the North. They are a peaceable people but an earnest people, and they will fight, too. They are not going to let this country be destroyed without a mighty effort to save it … Besides, where are your men and appliances of war to contend against them? The North can make a steam engine, locomotive, or railway car; hardly a yard of cloth or pair of shoes can you make. You are rushing into war with one of the most powerful, ingeniously mechanical, and determined people on Earth — right at your doors. You are bound to fail. Only in your spirit and determination are you prepared for war. In all else you are totally unprepared, with a bad cause to start with. At first you will make headway, but as your limited resources begin to fail, shut out from the markets of Europe as you will be, your cause will begin to wane. If your people will but stop and think, they must see in the end that you will surely fail.

- Comments to Prof. David F. Boyd at the Louisiana State Seminary (24 December 1860), as quoted in The Civil War : A Book of Quotations (2004) by Robert Blaisdell. Also quoted in The Civil War: A Narrative (1986) by Shelby Foote, p. 58.

All the congresses on earth can’t make the negro anything else than what he is; he must be subject to the white man… Two such races cannot live in harmony save as master and slave.[1]

1862 edit

Dispatch to Stephen A. Hurlbut (July 1862) edit

- No rebels shall be allowed to remain at Davis Mill so much as an hour. Allow them to go, but do not let them stay. And let it be known that if a farmer wishes to burn his cotton, his house, his family, and himself, he may do so. But not his corn. We want that.

- Dispatch to Brig. Gen. Stephen Hurlbut (July 1862)[specific citation needed]

1863 edit

Letter (June 1863) edit

- Vox populi, vox humbug.

- Letter to his wife (2 June 1863), as quoted in "The Oxford Dictionary of American Quotations" (2005) edited by Hugh Rawson and Margaret Miner.

1864 edit

- You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our Country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out.

- Retort to a lady of Confederate sympathies, who berated him for the wasting of Mississippi by the Army of the Tennessee during the Meridian Campaign ; cited in The Civil War Generation, Norman K. Risjord, Rowman & Littlefield (2002), p. 143 : ISBN 0742521699 , and in Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War and Reconstruction, Allen C. Guelzo, Oxford University Press (2012), p. 439 : ISBN 0199843295

- I am satisfied, and have been all the time, that the problem of this war consists in the awful fact that the present class of men who rule the South must be killed outright rather than in the conquest of territory.

- Letter to Sheridan (November 1864)

- I regard the death and mangling of a couple thousand men as a small affair, a kind of morning dash — and it may be well that we become so hardened.

- Letter to his wife (July 1864)[specific citation needed]

- I can make this march, and I will make Georgia howl!

- Telegram to General U.S. Grant (1864), as quoted in Conflict and Compromise : The Political Economy of Slavery, Emancipation, and The American Civil War (1989) by Roger L. Ransom.

- I am damned smarter man than Grant. I know more about military history, strategy, and grand tactics than he does. I know more about supply, administration, and everything else than he does. I'll tell you where he beats me though and where he beats the world. He doesn't give a damn about what the enemy does out of his sight, but it scares me like hell. … I am more nervous than he is. I am more likely to change my orders or to countermarch my command than he is. He uses such information as he has according to his best judgment; he issues his orders and does his level best to carry them out without much reference to what is going on about him and, so far, experience seems to have fully justified him.

- Comments to James H. Wilson (22 October 1864), as quoted in Under the Old Flag: Recollections of Military Operations in the War for the Union, the Spanish War, the Boxer Rebellion, etc Vol. 2 (1912) by James Harrison Wilson, p. 17.

Letter to R.M. Sawyer (January 1864) edit

If they want eternal war, well and good; we accept the issue, and will dispossess them and put our friends in their place. I know thousands and millions of good people who at simple notice would come to North Alabama and accept the elegant houses and plantations there. If the people of Huntsville think different, let them persist in war three years longer, and then they will not be consulted. Three years ago by a little reflection and patience they could have had a hundred years of peace and prosperity, but they preferred war; very well. Last year they could have saved their slaves, but now it is too late.

All the powers of earth cannot restore to them their slaves, any more than their dead grandfathers. Next year their lands will be taken, for in war we can take them, and rightfully, too, and in another year they may beg in vain for their lives. A people who will persevere in war beyond a certain limit ought to know the consequences. Many, many peoples with less pertinacity have been wiped out of national existence.

- Letter to Major R.M. Sawyer (31 January 1864), from Vicksburg.

Letter to James Guthrie (August 1864) edit

- I regret exceedingly the arrest of many gentlemen and persons in Kentucky, and still more that they should give causes of arrest. I cannot in person inquire into these matters, but must leave them to the officer who is commissioned and held responsible by Government for the peace and safety of Kentucky. It does appear to me when our national integrity is threatened and the very fundamental principles of all government endangered that minor issues should not be made by Judge Bullitt and others. We cannot all substitute our individual opinions, however honest, as the test of authority. As citizens and individuals we should waive and abate our private notions of right and policy to those of the duly appointed agents of the Government, certain that if they be in error the time will be short when the real principles will manifest themselves and be recognized. In your career how often have you not believed our Congress had adopted a wrong policy and how short the time now seems to you when the error rectified itself or you were willing to admit yourself wrong.

- I notice in Kentucky a disposition to cry against the tyranny and oppression of our Government. Now, were it not for war you know tyranny could not exist in our Government; therefore any acts of late partaking of that aspect are the result of war; and who made this war? Already we find ourselves drifting toward new issues, and are beginning to forget the strong facts of the beginning. You know and I know that long before the North, or the Federal Government, dreamed of war the South had seized the U.S. arsenals, forts, mints, and custom-houses, and had made prisoners of war of the garrisons sent at their urgent demand to protect them 'against Indians, Mexicans, and negroes'.

- I know this of my own knowledge, because when the garrison of Baton Rouge was sent to the Rio Grande to assist in protecting that frontier against the guerrilla Cortina, who had cause of offense against the Texan people, Governor Moore made strong complaints and demanded a new garrison for Baton Rouge, alleging as a reason that it was not prudent to have so much material of war in a parish where there were 20,000 slaves and less than 5,000 whites, and very shortly after this he and Bragg, backed by the militia of New Orleans, made 'prisoners of war' of that very garrison, sent there at their own request.

- You also remember well who first burned the bridges of your railroad, who forced Union men to give up their slaves to work on the rebel forts at Bowling Green, who took wagons and horses and burned houses of persons differing with them honestly in opinion, when I would not let our men burn fence rails for fire or gather fruit or vegetables though hungry, and these were the property of outspoken rebels. We at that time were restrained, tied by a deep seated reverence for law and property. The rebels first introduced terror as a part of their system, and forced contributions to diminish their wagon trains and thereby increase the mobility and efficiency of their columns. When General Buell had to move at a snail's pace with his vast wagon trains, Bragg moved rapidly, living on the country. No military mind could endure this long, and we are forced in self defense to imitate their example. To me this whole matter seems simple. We must, to live and prosper, be governed by law, and as near that which we inherited as possible. Our hitherto political and private differences were settled by debate, or vote, or decree of a court. We are still willing to return to that system, but our adversaries say no, and appeal to war. They dared us to war, and you remember how tauntingly they defied us to the contest. We have accepted the issue and it must be fought out. You might as well reason with a thunder-storm.

- War is the remedy our enemies have chosen. Other simple remedies were within their choice. You know it and they know it, but they wanted war, and I say let us give them all they want; not a word of argument, not a sign of let up, no cave in till we are whipped or they are.

Telegram to Abraham Lincoln (September 1864) edit

- Atlanta is ours, and fairly won.

- Telegram to President Abraham Lincoln (2 September 1864)[specific citation needed]

Letter to Henry W. Halleck (September 1864) edit

- If the people raise a howl against my barbarity and cruelty, I will answer that war is war, and not popularity-seeking. If they want peace, they and their relatives must stop the war.

- Letter to Henry W. Halleck (September 1864).

Letter to the City of Atlanta (September 1864) edit

- You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out. I know I had no hand in making this war, and I know I will make more sacrifices today than any of you to secure peace. But you cannot have peace and a division of our country. If the United States submits to a division now, it will not stop, but will go on until we reap the fate of Mexico, which is eternal war. The United States does and must assert its authority, wherever it once had power; for, if it relaxes one bit to pressure, it is gone, and I believe that such is the national feeling.

- You might as well appeal against the thunder-storm as against these terrible hardships of war. They are inevitable, and the only way the people of Atlanta can hope once more to live in peace and quiet at home, is to stop the war, which can only be done by admitting that it began in error and is perpetuated in pride.

- We do want and will have a just obedience to the laws of the United States. That we will have, and, if it involves the destruction of your improvements, we cannot help it.

- You have heretofore read public sentiment in your newspapers, that live by falsehood and excitement; and the quicker you seek for truth in other quarters, the better. I repeat then that, by the original compact of government, the United States had certain rights in Georgia, which have never been relinquished and never will be; that the South began the war by seizing forts, arsenals, mints, custom-houses, etc., etc., long before Mr. Lincoln was installed, and before the South had one jot or tittle of provocation. I myself have seen in Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi, hundreds and thousands of women and children fleeing from your armies and desperadoes, hungry and with bleeding feet. In Memphis, Vicksburg, and Mississippi, we fed thousands and thousands of the families of rebel soldiers left on our hands, and whom we could not see starve. Now that war comes to you, you feel very different. You deprecate its horrors, but did not feel them when you sent car-loads of soldiers and ammunition, and moulded shells and shot, to carry war into Kentucky and Tennessee, to desolate the homes of hundreds and thousands of good people who only asked to live in peace at their old homes, and under the Government of their inheritance. But these comparisons are idle. I want peace, and believe it can only be reached through union and war, and I will ever conduct war with a view to perfect an early success.

Signal to John M. Corse (October 1864) edit

- Hold the fort! I am coming!

- [The actual messages were "Sherman is coming. Hold out," and "General Sherman says hold fast. We are coming."[citation needed] This was changed to "Hold the fort" in a popular hymn by Philip Paul Bliss.[specific citation needed]]

- Signal to Gen. John M. Corse at Allatoona (5 October 1864)[specific citation needed]

Telegram to Abraham Lincoln (December 1864) edit

- I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty guns and plenty of ammunition, also about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton.

- Telegraph to Abraham Lincoln (December 1864), as quoted in Southern Storm: Sherman's March to the Sea (2008), by Noah Andre Trudeau, New York: HarperCollins, p. 508.

1865 edit

Special Field Order No. 15 (January 1865) edit

- "Special Field Order No. 15" (16 January 1865), Savannah, Georgia.

- At Beaufort, Hilton Head, Savannah, Fernandina, St. Augustine, and Jacksonville, the blacks may remain in their chosen or accustomed vocations; but on the islands, and in the settlements hereafter to be established no white person whatever, unless military officers and soldiers detailed for duty, will be permitted to reside; and the sole and exclusive management of affairs will be left to the freed people themselves, subject only to the United States military authority, and the acts of Congress. By the laws of war, and orders of the President of the United States, the negro is free, and must be dealt with as such. He cannot be subjected to conscription, or forced military service, save by the written orders of the highest military authority of the department, under such regulations as the President or Congress may prescribe. Domestic servants, blacksmiths, carpenters, and other mechanics, will be free to select their own work and residence, but the young and able-bodied negroes must be encouraged to enlist as soldiers in the service of the United States, to contribute their share toward maintaining their own freedom, and securing their rights as citizens of the United States.

Letter to James E. Yeatman (May 1865) edit

- I confess without shame that I am tired & sick of war. Its glory is all moonshine. Even success, the most brilliant is over dead and mangled bodies […] It is only those who have not heard a shot, nor heard the shrills & groans of the wounded & lacerated (friend or foe) that cry aloud for more blood & more vengeance, more desolation & so help me God as a man & soldier I will not strike a foe who stands unarmed & submissive before me but will say ‘Go sin no more.’

- Letter to James E. Yeatman of St. Louis, Vice-President of the Western Sanitary Commission (21 May 1865). As quoted on p. 358, and footnoted on p. 562, in Sherman: A Soldier's Passion For Order (2007), John F. Marszalek, Southern Illinois University Press, Chapter 15 ('Fame Tarnished')

- Variant text: I confess, without shame, that I am sick and tired of fighting — its glory is all moonshine; even success the most brilliant is over dead and mangled bodies, with the anguish and lamentations of distant families, appealing to me for sons, husbands, and fathers […] it is only those who have never heard a shot, never heard the shriek and groans of the wounded and lacerated […] that cry aloud for more blood, more vengeance, more desolation. […] I declare before God, as a man and a soldier, I will not strike a foe who stands unarmed and submissive before me, but would rather say—‘Go, and sin no more.’

- As quoted in Sherman: Merchant of Terror, Advocate of Peace (1992), Charles Edmund Vetter, Pelican Publishing, p. 289

- Variant text: I confess, without shame, that I am sick and tired of fighting — its glory is all moonshine; even success the most brilliant is over dead and mangled bodies, with the anguish and lamentations of distant families, appealing to me for sons, husbands, and fathers. You, too, have seen these things, and I know that you are also tired of the war, and are willing to let the civil tribunals resume their place. As far as I know, all the fighting men of our army want peace; and it is only those who have never heard a shot, never heard the shriek and groans of the wounded and lacerated (friend or foe), that cry aloud for more blood, more vengeance, more desolation. I know the rebels are whipped to death, and I declare before God, as a man and a soldier, I will not strike a foe who stands unarmed and submissive before me, but would rather say — ‘Go, and sin no more.’

- As quoted in Sherman: Soldier - Realist - American (1993) [1929] B. H. Liddell Hart, Da Capo Press, p.402

- See the Discussion Page for more extensive sourcing information.

Letter to his wife Ellen Sherman (April 9 1865) edit

- "As a rule don't borrow. 'Tis more honest to steal,"

1867 edit

We must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux … even to their extermination, men, women, and children.[2][3]

1870s edit

- War is Hell.

- This quote originates from his address to the graduating class of the Michigan Military Academy (19 June 1879); but slightly varying accounts of this speech have been published:

- I’ve been where you are now and I know just how you feel. It’s entirely natural that there should beat in the breast of every one of you a hope and desire that some day you can use the skill you have acquired here.

Suppress it! You don’t know the horrible aspects of war. I’ve been through two wars and I know. I’ve seen cities and homes in ashes. I’ve seen thousands of men lying on the ground, their dead faces looking up at the skies. I tell you, war is Hell!- As quoted from accounts by Dr. Charles O. Brown in the Battle Creek Enquirer and News (18 November 1933).

- Variants:

- There is many a boy here today who looks on war as all glory, but, boys, it is all Hell.

- Some of you young men think that war is all glamour and glory, but let me tell you, boys, it is all Hell!

1871 edit

Interview (June 1871) edit

- I hereby state, and mean all I say, that I never have been and never will be a candidate for President; that if nominated by either party I should peremptorily decline; and even if unanimously elected I should decline to serve.

- Interview in Harper's Weekly (24 June 1871).

1879 edit

Speech (June 1879) edit

Wars do not usually result from just causes but from pretexts. There probably never was a just cause why men should slaughter each other by wholesale, but there are such things as ambition, selfishness, folly, madness, in communities as in individuals, which become blind and bloodthirsty, not to be appeased save by havoc, and generally by the killing of somebody else than themselves.

- Speech to the graduating class of the Michigan Military Academy

1880s edit

1884 edit

Telegram (1884) edit

- I will not accept if nominated, and will not serve if elected.

- Telegram sent to General Henderson in 1884, refusing to run in the United States presidential election of that year. As quoted in Sherman's Memoirs, 4th ed. 1891. This is often paraphrased: If nominated, I will not run; if elected, I will not serve.

1885 edit

- It will be a thousand years before Grant's character is fully appreciated. Grant is the greatest soldier of our time if not all time... he fixes in his mind what is the true objective and abandons all minor ones. He dismisses all possibility of defeat. He believes in himself and in victory. If his plans go wrong he is never disconcerted but promptly devises a new one and is sure to win in the end. Grant more nearly impersonated the American character of 1861-65 than any other living man. Therefore he will stand as the typical hero of the great Civil War in America.

- On Ulysses S. Grant (1885), as quoted in Grant's Final Victory: Ulysses S. Grant's Heroic Last Year (2011), by Charles Bracelen Flood.

1889 edit

Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman (1889) edit

- An army to be useful must be a unit, and out of this has grown the saying, attributed to Napoleon, but doubtless spoken before the days of Alexander, that an army with an inefficient commander was better than one with two able heads.

- As quoted in Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman, 2nd ed., D. Appleton & Co., 1913 (1889). Reprinted by Project Gutenberg, 2014.

- My aim then was to whip the rebels, to humble their pride, to follow them to their inmost recesses, and make them fear and dread us. 'Fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom.' I did not want them to cast in our teeth what General Hood had once done at Atlanta, that we had to call on their slaves to help us to subdue them. But, as regards kindness to the race ..., I assert that no army ever did more for that race than the one I commanded at Savannah.

- As quoted in Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman, 2nd ed., D. Appleton & Co., 1913 (1889). Reprinted by Project Gutenberg, 2014.

1890s edit

1891 edit

- Slavery was the cause... [O]ur success was to be his freedom.

- Memoirs of General W. T. Sherman (1891), New York, pp. 2:180–81

Quotes about Sherman edit

For Freedom and her train

Sixty miles in latitude

Three hundred to the main

Treason fled before us

For resistance was in vain

While we were marching through Georgia ~ Henry Clay Work

Hurrah! Hurrah! the flag that makes you free!

So we sang the chorus from Atlanta to the sea,

While we were marching through Georgia.~ Henry Clay Work

- William Tecumseh Sherman, although not a career military commander before the war, would become one of "the most widely renowned of the Union’s military leaders next to U. S. Grant.”

Sherman, one of eleven children, was born into a distinguished family. His father had served on the Supreme Court of Ohio until his sudden death in 1829, leaving Sherman and his family to stay with several friends and relatives. During this period, Sherman found himself living with Senator Thomas Ewing, who obtained an appointment for Sherman to the United States Military Academy, and he graduated sixth in the class of 1840. His early military career proved to be anything but spectacular. He saw some combat during the Second Seminole War in Florida, but unlike many of his colleagues, did not fight in the Mexican-American War, serving instead in California. As a result, he resigned his commission in 1853. He took work in the fields of banking and law briefly before becoming the superintendent of the Louisiana Military Academy in 1859. At the outbreak of the Civil War, however, Sherman resigned from the academy and headed north, where he was made a colonel of the 13th United States Infantry.- American Battlefield Trust, "William T. Sherman"

- Sherman first saw combat at the Battle of First Manassas, where he commanded a brigade of Tyler’s Division. Although the Union army was defeated during the battle, President Abraham Lincoln was impressed by Sherman’s performance and he was promoted to brigadier general on August 7, 1861, ranking seventh among other officers at that grade. He was sent to Kentucky to begin the Union task of keeping the state from seceding. While in the state, Sherman expressed his views that the war would not end quickly, and he was replaced by Don Carlos Buell. Sherman was moved to St. Louis, where he served under Henry W. Halleck and completed logistical missions during the Union capture of Fort Donelson. During the Battle of Shiloh, Sherman commanded a division, but was overrun during the battle by Confederates under Albert Sydney Johnston. Despite the incident, Sherman was promoted to major general of volunteers on May 1, 1862.

After the battle of Shiloh, Sherman led troops during the battles of Chickasaw Bluffs and Arkansas Post, and commanded XV Corps during the campaign to capture Vicksburg. At the Battle of Chattanooga Sherman faced off against Confederates under Patrick Cleburne in the fierce contest at Missionary Ridge. After Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to commander of all the United States armies, Sherman was made commander of all troops in the Western Theatre, and began to wage warfare that would bring him great notoriety in the annals of history.- American Battlefield Trust, "William T. Sherman"

- By 1864 Sherman had become convinced that preservation of the Union was contingent not only on defeating the Southern armies in the field but, more importantly, on destroying the Confederacy's material and psychological will to wage war. To achieve that end, he launched a campaign in Georgia that was defined as “modern warfare”, and brought “total destruction…upon the civilian population in the path of the advancing columns [of his armies].” Commanding three armies, under George Henry Thomas, James B. McPherson, and John M. Schofield, he used his superior numbers to consistently outflank Confederate troops under Joseph E. Johnston, and captured Atlanta on September 2, 1864. The success of the campaign ultimately helped Lincoln win reelection. After the fall of Atlanta, Sherman left the forces under Thomas and Schofield to continue to harass the Confederate Army of Tennessee under John Bell Hood. Meanwhile, Sherman cut off all communications to his army and commenced his now-famous “March to the Sea," leaving in his wake a forty to sixty mile-wide path of destruction through the heartland of Georgia. On December 21, 1864 Sherman wired Lincoln to offer him an early Christmas present: the city of Savannah.

- American Battlefield Trust, "William T. Sherman"

- Maj.Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, [ United States Military Academy Class of] 1840 (Union): U.S. Grant's top lieutenant. He fought at Shiloh and in the Vicksburg, Chattanooga, Atlanta, and Carolina campaigns. His Savanna Campaign- the "March to the Sea"- brought total war to the people of the South. He served as commanding general of the US Army from 1869 to 1883.

- Alan Axelrod, Armies North, Armies South: The Military Forces of the Civil War Compared and Contrasted (2022), Essex: Lyons Press, paperback, p. 19

- A suspicion that rain had been falling rather steadily came also from a new onslaught on the situation by Fogarty. He led his troops onto the field, all armed with cans of gasoline, which were showered at strategic points in the infield. Having the enemy thus cornered temporarily, Brigadier General Fogarty took a ruthless turn reminiscent of Sherman's march to the sea. In short, Fogarty applied the torch and in a trice, as we say, the infield was a mass of flame and smoke.

- Havey J. Boyle (sports editor, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette), "Mirrors of Sport: It Must Have Rained; Fogarty Applies the Torch" (13 June 1938), The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

- He come through Madison on his march to the sea and we chillun hung out on the front fence from early morning unil late in the evening, watching the soldiers go by. It took most of the day…The next week…Miss Emily called the five women that wuz on the place and tole them to stay 'round the house... She said they were free and could go wherever they wanted to.

- It is difficult to determine whether Georgians hated Sherman and his army as much as the Spartans despised Epaminondas and the Thebans. Both men had wrecked their centuries-old practice of apartheid in a matter of weeks. It is a dangerous and foolhardy thing for a slaveholding society to arouse a democracy of such men.

- Victor Davis Hanson, The Soul of Battle: From Ancient Times to the Present Day, How Three Great Liberators Vanquished Tyranny (1999), New York City: The Free Press, p. 9

- The southern slave's eagerness to be free and willingness not just to leave but to fight, the Union army's embrace of their plight, the physical destruction of the plantation, and the psychological humiliation of the plantation class, all this illustrated that an apartheid state, once cracked, shatters and can never be reconstituted again. From the freeing of the slaves Sherman's men gained the moral imperative... In turn, from Sherman's men the slaves at last could prove they too were human, even more humane than their masters.

- Victor Davis Hanson, The Soul of Battle: From Ancient Times to the Present Day (1999), New York City: The Free Press, p. 210

- Historians identify General Sherman as its main architect, and the army principally responsible for the demise of the buffalo. Even Congress stepped in to try to curb the carnage; despite its attempt to pass legislation in 1874 to limit the buffalo slaughter, Sherman's malicious genius proved triumphant when army veteran and president Ulysses S. Grant vetoed the legislation.

- Dina Gilio-Whitaker As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock (2019)

- These members of the audience could point with pride to the Lincoln Zouaves, a colored military unit from Baltimore, resplendent in their tasseled fezzes, baggy red pants, white leggings, and red-trimmed black jackets. Colored spectators sang along when musicians struck up 'Marching Through Georgia', the Civil War ditty celebrating General William Tecumseh Sherman's drive from Atlanta to the sea.

- Charles Lane, The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction (2008), Henry Holt and Company, LLC, New York City, New York, p. 2

- Some Confederate soldiers switched sides, beginning as early as 1862. When Sherman made his famous march to the sea from Atlanta to Savannah, his army actually grew in number, because thousands of white southerners volunteered along the way. Meanwhile, almost two-thirds of the Confederate army disappeared through desertion. Eighteen thousand slaves joined Sherman, so many that the army had to turn some away. Compare these facts with the portrait common in our textbooks of Sherman's marauders looting their way through a united south. The increasing ideological confusion in the Confederate states, coupled with the increasing strength of the United States, helps explains the Union victory... Many nations and people have continued to fight with far inferior means and weapons... The Confederacy's ideological contradictions were its gravest liabilities, ultimately causing its defeat.

- James Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong (2007), New York: New Press, pp. 224–226

- In his fast-moving campaigns in the Civil War, Union General William T. Sherman habitually sought to threaten two objectives before he attacked. This forced the Confederate generals to split their forces, giving Sherman a decisive edge when he made his lunge.

- James Mattis, Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead (2019), p. 57

- General Sherman, who had lived in the South, liked Southerners and did not at all sympathize with Northern racial views, yet became the most hated and feared destroyer of the South and its whole civilization. And I think he did so because he saw that as necessary to win the war. And I think Lincoln made some of his decisions—issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, for example, or turning Sherman loose — because he saw that as necessary to win the war.

- James M. McPherson, as quoted in "An exchange with a Civil War historian" (19 June 1995), by David Walsh, International Workers Bulletin

- So it was in the civil war. Farragut's father was born in Spain and Sheridan's father in Ireland; Sherman and Thomas were of English and Custer of German descent; and Grant came of a long line of American ancestors whose original home had been Scotland. But the Admiral was not a Spanish-American; and the Generals were not Scotch-Americans or Irish-Americans or English-Americans or German-Americans. They were all Americans and nothing else. This was just as true of Lee and of Stonewall Jackson and of Beauregard.

- Theodore Roosevelt, "Address to the Knights of Columbus" (12 October 1915)

- In Tennessee, Sherman’s views on warfare changed. Originally he believed noncombatant populations and private property should be respected. However, guerrilla activity, civilian resistance, and the Confederate Army’s reliance on civilian supplies made Sherman realize civilian populations were vital to success in war. Wanting to find the fastest solution to end the war, he adopted the belief of total war. Sherman tried to demoralize the South by targeting economic support structures that enabled the war to continue. He wanted to destroy the South’s will to fight but maintained he would support the South when it laid down its arms; a claim validated by his actions after the war.

- Matthew Schaeffer, Tecumseh Sherman (1820-1891), North Carolina History Project

- Sherman remained widely popular after the war. Since his initial terms to Johnston were exceedingly generous, the South respected Sherman and looked to him for support during reconstruction. Sherman was an opponent of the Radical Republican Party and thought it was “Corrupt as Hell.” He helped his friends in the South and was vital in getting former Louisiana governor Thomas O. Moore’s plantation returned after it was confiscated. David French Boyd, founder of Louisiana State University, wrote to Sherman on September 22, 1865 and stated, “You were mainly instrumental in our discomfiture; yet the very liberal terms you proposed to grant us thro’ Joe Johnston and your course since have led the people of the South to expect more from you than any of the high northern officials.”

Following the war, Sherman was given command of the newly created Military Division of Missouri, which included the entire army west of the Mississippi River. Sherman was the commanding officer of the Indian Wars and carried over the strategy of total war. The Indians were faced with the decision of moving to the reservation or extermination. When Grant became General of the Army on July 25, 1866, Sherman was promoted to lieutenant general. After Grant became President of the United States in 1869, Sherman became commanding general of the United States Army. Sherman served as the commanding general until he retired on November 1, 1883. In 1875 he published a Memoirs (2 volumes) recounting his life and military career. When talk began of electing Sherman as president, Sherman, disgusted with politics, responded, “I will not accept if nominated and will not serve if elected.” He spent the last few years of his life in New York City and died on February 14, 1891.- Matthew Schaeffer, Tecumseh Sherman (1820-1891), North Carolina History Project

- For most of my life, I viewed plantations exclusively through the lens of the white planter class. Growing up, I learned the great sin of the Civil War was General William Tecumseh Sherman's infamous March to the Sea and his supposed indiscriminate, illegal, and immoral burning of private property. Actually, Sherman's hard-war policy was purposeful and directed, causing few civilian casualties. After reading about the enslaved experience, I find it hard to feel sorry for the planters.

- Ty Seidule, Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner's Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause (2020), p. 33

- The Appomattox surrender document still had wet ink when Lee gave General Orders No. 9, his farewell address, to the Army of Northern Virginia on April 10, 1865. Lee's address was the first salvo in what would become a written battle to define the meaning of the war. He argued that his army surrendered only because it had been "compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources." Not only did the United States have more of everything, it had Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman. Mitchell writes, "Grant was a butcher who did not care how many men he slaughtered for a victory, but a victory he would have." As for Sherman, Mitchell mentioned him seventy-two times, as though he carried a sulfurous pitchfork, leaving Sherman sentinels, the burned chimneys of plantation houses, in his wake. Only someone who fought without mercy and with unlimited resources of men and materiel could have defeated the virtuous Confederates. In reality, Grant and Sherman exhibited extraordinary generalship in a righteous cause.

- Ty Seidule, Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner's Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause (2020), p. 35

- I think Stone Mountain is amusing, but then again I find most representations of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson outside of Virginia, and, in Jackson's case, West Virginia, to be amusing. Aside from a short period in 1861-62, when Lee was placed in charge of the coastal defense of South Carolina and Georgia, neither general stepped foot in Georgia during the war. Lee cut off furloughs to Georgia's soldiers later in the war because he was convinced that once home they'd never come back. He resisted the dispatch of James Longstreet's two divisions westward to defend northern Georgia, and he had no answer when Sherman operated in the state.

- Brooks D. Simpson, "The Future of Stone Mountain" (22 July 2015), Crossroads, WordPress

- Returning home on leave following my second year at West Point, I called on a great-uncle who had joined the Confederate Army at the age of sixteen and had fought in a number of major Civil War battles, including Gettysburg, and had been with Robert E. Lee at Appamatox. My Uncle White was the younger brother of my grandfather. He hated Yankees and Republicans, not necessarily in that order, and talked derisively about both. When I visited, he was seated in a wheel chair, in grudging acquiescence to the infirmities of age. Tobacco juice decorated his shirt and stains around a spittoon on the floor testified to the inaccuracy of his aim. Flies buzzed through screenless windows. "What are you doing with yourself, son?" Uncle White asked. I answered the old veteran with trepidation. "I'm going to that same school that Grant and Sherman went to, the Military Academy at West Point, New York." Uncle White was silent for what seemed like a long time. "That's all right, son," he said at last. "Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson went there too."

- William Westmoreland, A Soldier Reports (1976), p. 12

- Bring the good old bugle, boys

We’ll sing another song

Sing it with a spirit that will

Start the world along

Sing it as we used to sing it

Fifty thousand strong

While we were marching through Georgia- Henry Clay Work, first verse of "Marching Through Georgia" (1865), which Work wrote to celebrate Sherman's highly-successful March to the Sea in 1864-1865, which destroyed much of the rebelling Confederacy's remaining industry and infrastructure. Sherman himself came to dislike the song, in part because it was played constantly when he made public appearances post-war.

- So we made a thoroughfare

For Freedom and her train

Sixty miles in latitude

Three hundred to the main

Treason fled before us

For resistance was in vain

While we were marching through Georgia- Henry Clay Work, fifth verse of "Marching Through Georgia" (1865)

- Hurrah! Hurrah! we bring the Jubilee!

Hurrah! Hurrah! the flag that makes you free!"

So we sang the chorus from Atlanta to the sea,

While we were marching through Georgia.- Henry Clay Work, chorus of "Marching Through Georgia" (1865)

External links edit

- Profile at The American Experience (PBS)

- U.S. Army Center of Military History

- Works by William Tecumseh Sherman at Project Gutenberg

- General William Tecumseh Sherman in Georgia

- William Tecumseh Sherman in California

- California military history

- Memoirs of General W. T. Sherman online

- Digitized collection of letters between William Sherman and his brother Senator John Sherman

- Sherman Thackara Collection of Letters at the Digital Library @ Villanova University

- William T. Sherman’s First Campaign of Destruction" Article by Buck T. Foster in Military History Quarterly

- Profile at Find a Grave