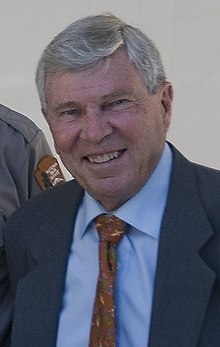

James M. McPherson

American historian (born 1936)

James M. "Jim" McPherson (born 11 October 1936) is an American historian, best known for his writings on the American Civil War.

Quotes

edit- In this study the term "abolitionist" will be applied to those Americans who before the Civil War had agitated for immediate, unconditional, and universal abolition of slavery in the United States. Contemporaries of the antislavery movement and later historians have sometimes mistakenly used the word "abolitionist" to describe adherents of the whole spectrum of antislavery sentiment. Members of the Free Soil and Republican parties have often been called abolitionists, even though these parties were pledged officially before 1861 only to the limitation of slavery, not to its extirpation. It is a moot question whether such radical anti-slavery leaders such as Charles Sumner, John Andrew, George Julian, Thaddeus Stevens, or Owen Lovejoy were genuine "abolitionists". In their hearts they probably desired an immediate end to slavery as fervently as did William Lloyd Garrison. But they were committed publicly by political affiliation and party responsibility to a set of principles that fell short of genuine abolitionism.

- James M. McPherson, The Struggle for Equality (1964) p. 3 [1]

1980s

edit- The Alabama Democratic convention [instructed] its delegates to walk out of the national convention if the party refused to adopt a platform pledging a federal slave code for the territories. Other lower-South Democratic organizations followed suit. In February, Jefferson Davis presented the substance of southern demands to the Senate in resolutions affirming that neither Congress nor a territorial legislature could impair the constitutional right of any citizen of the United States to take his slave property into the common territories.

- James M. McPherson. Battle Cry of Freedom (1988) p. 214

- What were these rights and liberties for which Confederates contended? The right to own slaves; the liberty to take this property into the territories.

- James M. McPherson. Battle Cry of Freedom (1988) p. 241

- To a good many southerners the events of 1861–1865 have been known as 'The War of Northern Aggression'. Never mind that the South took the initiative by seceding in defiance of an election of a president by a constitutional majority. Never mind that the Confederacy started the war by firing on the American flag. These were seen as preemptive acts of defense against northern aggression.

- James M. McPherson. "The War of Southern Aggression" (19 January 1989), The New York Review of Books

1990s

edit- Slavery was at the root of what the Civil War was all about. If there had been no slavery, there would have been no war, and that ultimately what the Confederacy was fighting for was to preserve a nation based on a social system that incorporated slavery. Had that not been the case, there would have been no war. That's an issue that a lot of Southern whites today find hard to accept.

- James M. McPherson "James McPherson: What They Fought For, 1861–1865" (22 May 1994), Booknotes, United States of America: National Cable Satellite Corporation. p.107

- Powerful racial prejudices? That was not true of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, or Norwood P. Hallowell, or George T. Garrison, or many other abolitionists and sons of abolitionists who became officers in black regiments. Indeed, the contrary was true. They had spent much of their lives fighting the race prejudice endemic in American society, sometimes at the risk of their careers and even their lives. That is why they jumped at the chance of help launch an experiment with black soldiers which they hoped would help African Americans.

- James M. McPherson. Drawn with the Sword : Reflections on the American Civil War (1996), Princeton University: Oxford University Press. p. 91

- Rioters were mostly Irish Catholic immigrants and their children. They mainly attacked the members of New York's small black population. For a year, Democratic leaders had been telling their Irish-American constituents that the wicked Black Republicans were waging the war to free the slaves who would come north and take away the jobs of Irish workers. The use of black stevedores as scabs in a recent strike by Irish dockworkers made this charge seem plausible. The prospect of being drafted to fight to free the slaves made the Irish even more receptive to demogogic rhetoric.

- James M. McPherson. Drawn with the Sword : Reflections on the American Civil War] (1996), Princeton University: Oxford University Press. pp. 91–92

An Exchange With a Civil War Historian (June 1995)

editJames M. McPherson. "An exchange with a Civil War historian" (19 June 1995), by David Walsh, International Workers Bulletin, World Socialist Web Site.

- There are all kinds of myths that a people has about itself, some positive, some negative, some healthy and some not healthy. I think that one job of the historian is to try to cut through some of those myths and get closer to some kind of reality. So that people can face their current situation realistically, rather than mythically. I guess that's my sense of what a historian ought to do.

- What has changed is that I've gained a lot more sympathy for Lincoln. At the time I was doing my dissertation I tended to take the Wendell Phillips view of Lincoln. Why didn't he move more quickly? Why was he so conservative on some of these issues? Why didn't he seize this revolutionary moment? The more I've learned about it, the more I realize that Lincoln was under extraordinary pressure from all sides. In his position he could not have acted like Wendell Phillips. He would have lost the whole war.

- The great crisis facing the country was the rebellion and anybody in the North who wanted to preserve the Union now found the principal enemy to be those Southern slave owners who had broken up the country. The institution which sustained them and the institution they went to war to defend was slavery. And more and more northerners became convinced of that. As a consequence, a lot of them went the whole way over, from being conservative, pro-Southern, pro-slavery Democrats to becoming radical Republicans. Benjamin Butler is a good example, and Edwin M. Stanton is another one.

- General Sherman, who had lived in the South, liked Southerners and did not at all sympathize with Northern racial views, yet became the most hated and feared destroyer of the South and its whole civilization. And I think he did so because he saw that as necessary to win the war. And I think Lincoln made some of his decisions—issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, for example, or turning Sherman loose — because he saw that as necessary to win the war.

- The risk of making a decision that's wrong is so enormous that sometimes it just crushes people so that they can't make any decision at all because they're afraid of making the wrong decision. And that's exactly what McClellan's problem was.

- People are going to dislike you if you make a decision, even if it turns out to be the right one.

- Lincoln. His commitment to preserving the United States was so strong and so deep that he was willing to do whatever it took to succeed. Would you like to be in his shoes? Just think about that for a moment. Not just Lincoln. There are hundreds of examples in history.

For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War (1997)

editJames M. McPherson For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War] (1997), New York City, New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.

- These soldiers were using the word slavery in the same way that Americans in 1776 had used it to describe their subordination to Britain. Unlike many slaveholders in the age of Thomas Jefferson, Confederate soldiers from slaveholding families expressed no feelings of embarrassment or inconsistency in fighting for their own liberty while holding other people in slavery. Indeed, white supremacy and the right of property in slaves were at the core of the ideology for which Confederate soldiers fought.

- p. 106

- It would be wrong, however, to assume that Confederate soldiers were constantly preoccupied with this matter. In fact, only 20 percent of the sample of 429 Southern soldiers explicitly voiced proslavery convictions in their letters or diaries. As one might expect, a much higher percentage of soldiers from slaveholding families than from nonslaveholding families expressed such a purpose: 33 percent, compared with 12 percent. Ironically, the proportion of Union soldiers who wrote about the slavery question was greater, as the next chapter will show. There is a ready explanation for this apparent paradox. Emancipation was a salient issue for Union soldiers because it was controversial. Slavery was less salient for most Confederate soldiers because it was not controversial. They took slavery for granted as one of the Southern 'rights' and institutions for which they fought, and did not feel compelled to discuss it. Although only 20 percent of the soldiers avowed explicit proslavery purposes in their letters and diaries, none at all dissented from that view. But even those who owned slaves and fought consciously to defend the institution preferred to discourse upon liberty, rights, and the horrors of subjugation.

- pp. 109–110

2000s

edit- The bottom line in the Civil War, after all is said and done, showed that every Confederate state was a slave state and every free state was a Union state. These facts were not a coincidence, and every Civil War soldier knew it.

- North & South Magazine (January 2008), Vol. 10, No. 4, p. 59

- Interpretations of the past are subject to change in response to new evidence, new questions asked of the evidence, new perspectives gained by the passage of time.

- James M. McPherson. "Revisionist Historians" (September 2003), Perspectives, American Historical Association.

- The unending quest of historians for understanding the past — that is, 'revisionism' — is what makes history vital and meaningful.

- James M. McPherson. "Revisionist Historians" (September 2003), Perspectives, American Historical Association.

- Defeat would blot the Confederate States of America from the face of the earth. Confederate victory would destroy the United States and create a precedent for further balkanization of the territory once governed under the Constitution of 1789.

- James M. McPherson. "No Peace without Victory, 1861–1865" (2003), American Historical Association

- By the time of the Gettysburg Address, in November 1863, the North was fighting for a 'new birth of freedom' to transform the Constitution written by the founding fathers, under which the United States had become the world's largest slaveholding country, into a charter of emancipation for a republic where, as the northern version of 'The Battle Cry of Freedom' put it, 'Not a man shall be a slave'.

- James M. McPherson. The Illustrated Battle Cry of Freedom (2003)

- While one or more of these interpretations remain popular among the Sons of Confederate Veterans and other Southern heritage groups, few professional historians now subscribe to them. Of all these interpretations, the states' rights argument is perhaps the weakest. It fails to ask the question, states' rights for what purpose? States' rights, or sovereignty, was always more a means than an end, an instrument to achieve a certain goal more than a principle.

- James M. McPhersonThis Mighty Scourge: Perspectives on the Civil War (2007), Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–9

- Southern political leaders were threatening to take their states out of the Union if a Republican president was elected on a platform restricting slavery.

- James M. McPhersonThis Mighty Scourge: Perspectives on the Civil War (2007), Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 188

- Lincoln was the only president in American history whose administration was bounded by war.

- James M. McPherson. Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief (2008) p. xiii

- If Lincoln had been a failure, he would have lived a longer life.

- James M. McPherson. Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief (2008) "Epilogue"

- Scorned and ridiculed by many critics during his presidency, Lincoln became a martyr and almost a saint after his death. His words and deeds lived after him, and will be revered as long as there is a United States. Indeed, it seems quite likely that without his determined leadership the United States would have ceased to be.

- James M. McPherson. Abraham Lincoln, (2009) p. 65

- More than any other American, Lincoln's name has gone into history. He gave all Americans, indeed all people everywhere, reason to remember that he had lived.

- James M. McPherson. Abraham Lincoln, (2009) p. 65

Quotes about James M. McPherson

edit- James M. McPherson has helped millions of Americans better understand the meaning and legacy of the American Civil War. By establishing the highest standards for scholarship and public education about the Civil War and by providing leadership in the movement to protect the nation's battlefields, he has made an exceptional contribution to historical awareness in America.

- William R. Ferris, NEH News (2000)

External links

edit- Encyclopedic article on James M. McPherson on Wikipedia