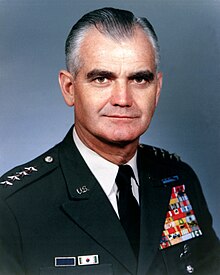

William Westmoreland

United States Army general (1914-2005)

William Childs Westmoreland (March 26, 1914 – July 18, 2005) was a United States Army general, who most notably commanded U.S. forces during the Vietnam War from 1964 to 1968. He served as Chief of Staff of the United States Army from 1968 to 1972.

Quotes

edit- Patton looked like his father and had similar mannerisms. Their speech was somewhat alike as well. It was pretty evident that young Patton was the son of the old man. However, the impressive thing about George is that he didn't concern himself with his last name. He went out and made a career, earning everything on his own... He did a very good job in command of the 11th ACR and handled himself professionally. It's quite a burden the son of a senior officer has to carry and I must say, to his credit, he did it well. Because down through history, when you look at the sons of famous people, they were not all winners.

- On George S. Patton, IV, son of the famous World War II American general. As quoted in The Fighting Pattons (1997) by Brian M. Sobel, p. 129-130

- The Green Beret... proudly worn by the United States Army Special Forces... and acclaimed by our late President, John F. Kennedy, as "a symbol of excellence, a badge of courage, a mark of distinction in the fight for freedom..." In Vietnam the men of Special Forces were the first to go. They frequently fought, not in great battles with front-page attention, but in places with foreign sounding, unknown names; and often times no names at all. One such place was Nam Dong. In July of 1964 this Special Forces Camp, in the jungle-clad mountains near the Laotian border, came under a fierce attack. It was the first time that regular North Vietnamese Army forces joined the Viet Cong in an attempt to overrun an American outpost. The North Vietnamese reinforced battalion of eight hundred men was determined to eliminate this camp- an impediment to their further infiltration down the Ho Chi Minh trail from Laos to the south of Vietnam. Roger H.C. Donlon, then a captain and, commander of Special Forces Detachment A-276 at Camp Nam Dong along with his brave twelve-man team, 60 Nungs and 100 loyal Vietnamese successfully defended the camp. For their valor two of his sergeants were posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Four other team members were awarded Silver Stars, and five more Bronze Stars with V for valor. Roger Donlon was the first soldier I recommended to receive the Medal of Honor for heroism which was later presented to him by President Lyndon Johnson. He was the first soldier of the Vietnam War to receive this award. "Beyond Nam Dong" is his personal story... from his scouting days as a boy in upstate New York, through the Vietnam conflict, to his present efforts at reconciliation. It is the inspiring story of a courageous soldier and patriot.

- Westmoreland's foreword to Beyond Nam Dong (1998) by Roger H.C. Donlon

A Soldier Reports (1976)

edit- To Kitsy, Stevie, Rip, and Margaret, and to the valiant men and women of the United States and other nations who served the cause of freedom in South Vietnam.

- Dedication

- Serving one's country as a military man is rewarding experience. It is nevertheless a life of constraint. A military man serves within carefully prescribed limits, be it as enlisted man, junior officer, battalion commander, division commander, even senior field commander in time of war. The freedom to speak out in the manner of the private citizen, journalist, politician, legislator has no part in the assignment. Perhaps this is one reason why generals who have hung up their uniforms traditionally turn to the pen, seek an opportunity for free expression that they have long denied themselves, to report to the people they have served. In these pages I have tried to exercise that prerogative that in the end is mine, while at the same time seeking to make an objective and constructive contribution to the history of a dramatic era. In the idiom of the time, I have tried to tell it like it was. This is my personal story, yet inevitably it represents more than that; for my story is inextricably involved with the stories of those who served with me during thirty-six years in the United States Army- from wooden-wheeled artillery to antiballistic missile, from horse to spaceship, from volunteer army to draftee army in three wars and back to volunteer army. My story is particularly involved with the stories of those who served with such valor and sacrifice in the Republic of Vietnam. My hope is that in telling my story I have in some manner done justice to theirs, that I have to some degree contributed to an appreciation by the American people of arduous, imaginative, valiant service in spite of alien environment, hardship, restriction, frustration, misunderstanding, and vocal and demonstrative opposition.

- From the Preface

- An officer corps, my West Point education emphasized, must have a code of ethics that tolerates no lying, no cheating, no stealing, no immorality, no killing other than that recognized under international rules of war and essential for military victory. Yet I also learned to my chagrin that there are those who fail the standards and that the code must be constantly policed. I saw failures at West Point, and for all my preventive efforts, I also saw failures among those who subsequently served under my command. Yet if an officer corps is to serve the nation as it should, firm dedication to a high moral code must always be the goal. One of the most exciting events of my plebe year was the commencement address by the Army Chief of Staff, General MacArthur, who was much as any man extolled such a code. Already a distinguished soldier even before World War II and the Korean War, General MacArthur spoke at a time when pacifism and economy imperiled the military services and the nation's security. While warning against misguided pacifism and politically inspired economy, he spoke of West Point as "the soul of the Army". "The military code that you perpetuate," he said, "has come down to us from even before the age of knighthood and chivalry. It will stand the test of any code of ethics or philosophy."

- p. 11.

- Returning home on leave following my second year at West Point, I called on a great-uncle who had joined the Confederate Army at the age of sixteen and had fought in a number of major Civil War battles, including Gettysburg, and had been with Robert E. Lee at Appamatox. My Uncle White was the younger brother of my grandfather. He hated Yankees and Republicans, not necessarily in that order, and talked derisively about both. When I visited, he was seated in a wheel chair, in grudging acquiescence to the infirmities of age. Tobacco juice decorated his shirt and stains around a spittoon on the floor testified to the inaccuracy of his aim. Flies buzzed through screenless windows. "What are you doing with yourself, son?" Uncle White asked. I answered the old veteran with trepidation. "I'm going to that same school that Grant and Sherman went to, the Military Academy at West Point, New York." Uncle White was silent for what seemed like a long time. "That's all right, son," he said at last. "Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson went there too."

- p. 12.

- As graduation neared, neither my classmates nor I could know, of course, that World War II was in the offing. It was destined to expose us to trying and often tragic events. My roommate, Billy Hulse, a flier, disappeared on a training mission over the Great Lakes, his body never recovered. A close friend, Frank Oliver, died in the fighting in Normandy soon after the invasion. Buist Dowling killed in Normandy while leading a patrol. One of the better football players, Jock Clifford, killed as a regimental commander on Okinawa. Bill Priestly, aide to the high commissioner of the Philippines, electing to stay when the fighting started on the islands, also killed. Those and more.

- p. 13.

- Despite a number of near misses, I came through the war unscathed. In Tunisia a shell hit my vehicle but without harm to me, and in Sicily an exploding mine blew up my vehicle, but I was thrown clear. On the Roer River in Germany, just as I got out of my Jeep and entered a company command post, a mortar shell struck my vehicle. In the Remagen bridgehead on the Rhine a shell demolished a latrine moments after I had departed. Somehow none of the enemy shells had my number.

- p. 18.

- Russians and vodka, I soon learned, were virtually synonymous. Twice I accompanied my division commander, General Craig, with his Russian opposite beyond the Elbe. Since General Craig was an abstainer, his aides had to exercise considerable ingenuity to dispose of the vodka from his glass in nearby flower pots. The Russian general several times did the same. I noted an unwavering peculiarity about the Russians: we always had to go to them; never would they come to visit us or even meet us halfway.

- p. 19.

- Being in Germany in the 1940s brought back recollections of my first visit long before as a Boy Scout, when I had had my first encounter with German appreciation of dueling. As as child I had been cut severely on the left cheek when thrown through the windshield of my father's car in a head-on collision, and a prominent scar remained. Traveling in Germany as a youth, I was perplexed when college students would tip their beanie hats as they passed until at last I discerned that they mistook the scar on my cheek for a dueling scar.

- p. 20.

- During the war years, it was my privilege to associate on a number of occasions with prominent personalities, such as Senator Harry S Truman, for whom my battalion staged an artillery demonstration when he visited Fort Bragg in 1941. When I invited him to fire, he did so with confidence. Shaking my hand as he departed, he said that as an old artilleryman he recognized that the fire mission was uncomplicated and that, even so, he suspected the crews had helped him hit the target. "I enjoyed it anyway," he said. When I was in Vietnam, a then former President Truman wrote me a letter of encouragement.

- p. 20.

- Among a stream of visitors to the 9th Division in England, while it was preparing for D-Day in the early months of 1944, was Prime Minister Winston Churchill. When he arrived to address the assembled troops, he went at first not to the speaker's stand but behind a small outbuilding. He reappeared minutes later buttoning his fly, making sure no one missed the reason for the delay. The troops loved it.

- p. 20.

- While in Sicily, I re-established an earlier acquaintance with a dynamic young colonel commanding one of the 82d Airborne's parachute infantry regiments, James M. Gavin, who later commanded the division. When the war was over, General Gavin asked my transfer to the division to command the 504th Parachute Infantry. Since I had yearned to be a paratrooper ever since serving at Fort Bragg in proximity to the first American airborne units, I was delighted at the assignment. I learned much from General Gavin in his capacity as a division commander, particularly on leadership qualities and maintaining the morale of the troops. More than any other commander under whom I served, he impressed me with the necessity for a commander to be constantly visible to those he leads.

- p. 21.

- Soon after the war- Jim Gavin told me to our amusement- the commandant of the Air War College, Major General Orvil A. Anderson, introduced him as a guest speaker. Anderson was a pioneer flier and balloonist, later fired from the Air Force by President Truman for preaching preventative war. "We were never more privileged," General Anderson intoned, "than we are today to have this distinguished speaker, one of America's great soldiers, one of the greatest since Lee, Grant, Pershing, a man who is going down in history as a tactician and strategist, one of the great soldiers of all time." Then General Anderson began to slow down. "One of the great soldiers of all time," he repeated. By that time it was apparent he was stalling. "One of the great soldiers of all time," he said again. Turning to Gavin, he asked in exasperation: "What the hell is your name anyway?"

- p. 21.

- I first met George S. Patton, Jr., before World War II when he was a lieutenant colonel at Fort Sill, and in North Africa, when he was a general, I saw him often. Almost every day he would head for the front, standing erect in his jeep, helmet and brass shining, a pistol on each hip, a siren blaring. For the return trip, either a light plane would pick him up or he would sit huddled, unrecognizable, in the jeep in his raincoat. His image with the troops was foremost with General Patton, and that meant always going forward, never backward. General Patton had two fetishes that to my mind did little for his image with the troops. First, he apparently loathed the olive drab wool cap that the soldier wore under his helmet for warmth and insisted that it be covered; woe be the soldier whom the general caught wearing the cap without the helmet. Second, he insisted that every soldier under his command always wear a necktie with shirt collar buttoned, even in combat action.

- p. 21.

I first met George S. Patton, Jr., before World War II when he was a lieutenant colonel at Fort Sill, and in North Africa, when he was a general, I saw him often. Almost every day he would head for the front, standing erect in his jeep, helmet and brass shining, a pistol on each hip, a siren blaring. For the return trip, either a light plane would pick him up or he would sit huddled, unrecognizable, in the jeep in his raincoat. His image with the troops was foremost with General Patton, and that meant always going forward, never backward.

- At the 9th Division headquarters at El Guettar, Tunisia, enemy planes bombed and strafed incessantly, so that the security normally associated with a headquarters in the rear was missing. Although officers and men alike dug deep, even in foxholes they could get little sleep. One day a small convoy of vehicles arrived, sirens alive, Patton standing in the lead vehicle. While the division commander, Major General Manton Eddy, rushed to greet him, the staff pondered what fault Patton would find this time. "Manton, Goddamn it," Patton shouted in his high-pitched voice, "I want you to get these staff officers out front and get them shot at!" Having been bombarded day and night by enemy planes, having had no sleep for days, a young personnel officer went berserk and had to be evacuated for medical treatment.

- p. 21.

- Several weeks before General Patton died in a command car accident in 1945, he visited my headquarters at Ingolstadt. Over lunch he remarked on a recent visit he had made to the United States where the press had castigated him for referring to the Nazis as a political party "like Republicans or Democrats". "Westy," he told me solemnly, "don't forget when you return to the States, be careful what you say. No matter what, they'll put it in the newspapers." It seemed remote advice at the time for a young, inauspicious colonel, but I was to have ample reason in later years to reflect on his counsel.

- p. 22.

- Raised an Army brat in a constantly changing scene, Kitsy has always been at ease in any company. While she enjoys formal affairs, she has such an air of informality that in her corner of the room ritual is soon dispensed with. Kitsy was much impressed with the wives of Vietnamese officials. If the Vietnamese men, she liked to say, were half as strong as their women, the country would have no problem. She enjoyed their sense of humor, their propensity for earthly jokes. When she had difficulty deciphering the mixture of languages and getting to the point, one or another of the ladies would take her aside and explain. Kitsy shares some of my lack of affinity for foreign languages; her attempts at French drew the same wry smiles as my attempts at Vietnamese. Kitsy's sense of humor has brightened many an occasion. At a ceremony unveiling my official superintendent's portrait at West Point, the master of ceremonies asked her to say a few words. "This is the second time I have seen Westy unveiled," said Kitsy. "The first time was on our wedding night."

- p. 263.

- Not long after I became U.S. Army Chief of Staff, the Secretary of the Army accepted my recommendation that the heads of the Army Nurse Corps and the Women's Army Corps be established as general officers. Soon after I had the honor of pinning stars on the first two female generals in the nation's history, Anna Mae Hays and Elizabeth P. Hosington (and establishing a tradition by giving each a kiss on the cheek), Kitsy found herself at the hairdresser's beside General Hays, a widow. "I wish you would get married again," Kitsy said. "Why?" General Hays asked. "Because," Kitsy responded, "I want some man to learn what it's like to be married to a general."

- p. 264.

"I wish you would get married again," Kitsy said. "Why?" General Hays asked. "Because," Kitsy responded, "I want some man to learn what it's like to be married to a general."

- The enemy had achieved in South Vietnam neither military nor psychological victory. For the South Vietnamese the Tet offensive served as a unifying catalyst, a Pearl Harbor. Had it been the same for the American people, had President Johnson discerned the same support behind him that Thieu did behind him, and had he acted with forcefulness, the enemy could have been induced to engage in serious and meaningful negotiations. Unfortunately, the enemy scored in the United States the psychological victory that eluded him in Vietnam, so influencing President Johnson and his civilian advisors that they ignored the maxim that when the enemy is hurting, you don't diminish the pressure, you increase it.

- p. 334.

- Khe Sanh will stand in history, I am convinced, as a classic example of how to defeat a numerically superior besieging force by co-ordinated application of firepower.

- p. 336.

- The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs has a difficult job living with his civilian bosses, the Secretary of Defense and the President, striving to convince them in terms they can understand matters that he views as military necessity, and, in General Wheeler's case, within the concept of one thing at a time. One thing at a time was all he could hope to accomplish. Since Vietnam was the visible part of the iceberg, the part he knew was perturbing his civilian bosses, Vietnam rather than the strategic reserve was the context in which to present the request for additional troops. If he could gain authority to raise the troops, exactly what was to be done with them could be decided once the troops were actually available.

- p. 357.

- As any television viewer or newspaper reader could discern the end in South Vietnam, in April 1975, came with incredible suddenness, amid scenes of unmitigated misery and shame. Utter defeat, panic, and rout have produced similar demoralizing tableaux through the centuries; yet to those of us who had worked so hard and long to try to keep it from ending that way, who had been so markedly conscious of the deaths and wounds of thousands of Americans and the soldiers of other countries, who had so long stood in awe of the stamina of the South Vietnamese soldier and civilian under the mantle of hardship, it was depressingly sad that so much misery should be a part of it. So immense had been the sacrifices made through so many long years that the South Vietnamese deserved an end- if it had to come to that- with more dignity to it.

- p. 396.

- There is, General Douglas MacArthur said, "no substitute for victory." For all who would face reality, the truth of those words was proven not only in South Vietnam but in all of Indochina.

- p. 402.

- Ignoring the restrictions which the United States imposed upon itself in conducting the war in Indochina, some observers have seen in the outcome some special military genius on the side of North Vietnam. They have in large measure attributed that alleged genius to my apparent counterpart, Vo Nyugen Giap. In reality, Giap was hardly my counterpart, for my position was never so exalted as Giap's. While he was apparently an influential member of his country's government, I was a field commander restricted to decisions and actions within the boundaries of South Vietnam, subject to the dictates of my country's government, and influential in policy matters only to the extent that Washington chose to act on my recommendations. Yet since Giap was for long his own field commander, there was enough direct confrontation between the two of us to enable me to some degree to analyze and judge his military performance.

- p. 404.

- In the renewed war in South Vietnam beginning in the late 1950s, the considerable success that Giap and the Viet Cong enjoyed was cut short by the introduction of American troops. In the face of American airpower, helicopter mobility, and fire support, there was no way Giap could win on the battlefield. Given the restrictions they had imposed on themselves, neither was there much chance that the Americans and South Vietnamese could win a conventional victory; but so long as American troops were involved, Giap could point to few battlefield successes more spectacular or meaningful than the occasional overrunning of a fire-support base. Yet Giap persisted nevertheless in a big-unit war in which his losses were appalling, as evidenced by his admission to the Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci that he had by early 1969 lost half a million men killed. Ruthless disregard for losses is seldom seen as military genius. A Western commander absorbing losses on the scale of Giap's would have hardly lasted in command more than a few weeks.

- p. 405.

- Forced in January 1973 by American pressure to to accept a cease-fire agreement that left well over 100,000 North Vietnamese troops inside South Vietnam and free access for tens of thousands more, South Vietnamese leaders surely had reason to believe that if their enemy seriously violated the agreement, the United States would interfere. Yet that was not to be. In the face of that grave psychological blow for the South Vietnamese, it required no military genius to assure South Vietnam's eventual military defeat.

- p. 405-406.

- Ironically, the North Vietnamese victory could have come much sooner. In view of the increasing commitment of American troops in the mid- and late 1960s, General Giap would have been well advised to abandon the big-unit war, pull in his horns to take away the visible threat to South Vietnam's survival, and thereby delude the Americans that they had already achieved their goal of making the South Vietnamese self-sufficient. President Johnson had given Giap that chance at the Manila conference of 1966 when he had announced that once "the level of violence subsides," American and other foreign troops would withdraw within six months. That would have been eight years before the eventual South Vietnamese defeat, long before the South Vietnamese armed forces would have had any claim to self-sufficiency. Making that offer at the Manila conference may well have been an effort by President Johnson to rid himself of the albatross of South Vietnam, whatever the long-range consequences. For once the United States had pulled out under those circumstances and Giap had come back, what American President would have dared risk the political pitfalls involved in putting American troops back in?

- p. 406.

- Dating from the days of the Geneva Accords of 1954, the refugees always flowed south, not north, and even those Americans who long maintained that the refugees were not fleeing the enemy but American shelling and bombing would have to admit that even after American shelling and bombing stopped, the flow was still always southward. So it was until the final deplorable end. How could anyone genuinely believe that the South Vietnamese people had no desire to forestall the march of totalitarianism, to maintain their freedom- however imperfect- when for years upon years they bore incredible hardships and their soldiers fought with courage and determination to do just that? They carried on the fight under a government that many Americans labeled unrepresentative, repressive, and corrupt. No people could have pursued such a grim defensive fight for so long without a deep underlying yearning for freedom.

- p. 409.

How could anyone genuinely believe that the South Vietnamese people had no desire to forestall the march of totalitarianism, to maintain their freedom- however imperfect- when for years upon years they bore incredible hardships and their soldiers fought with courage and determination to do just that?

- Had President Kennedy not pledged the nation to bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, and oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty?

- p. 409.

- Those of us in the military may have even underestimated the degree of support the American people still afforded the military, for a recent public opinion survey revealed that the military services are among the public institutions that the people trust most. For one looking back on thirty-six years of service in the United States Army, that is a rewarding thought. So, too, I am struck, upon reflection, by the unprecedented changes that occurred during those thirty-six years. From the World War I Stokes mortar and the Model 1897 French 75 artillery piece to sophisticated guided missiles; from the model 1902 rifle to the M-16; from carrier pigeons and Morse code telegraphy to walkie-talkies, computers, and sensors; from a private's pay of $21 a month and a second lieutenant's of $125 to today's private's pay of $344 a month and today's second lieutenant's of $634; through three wars and a number of police actions; from volunteer army back to volunteer army; and from isolationism to multiple international commitments. As one in the middle of the changes at various levels of command responsibility, I have always been impressed by the loyalty, flexibility, durability, and overall effectiveness of the United States Army. The traumatic experience of Vietnam was no exception.

- p. 424.

- Among some of my military colleagues I nevertheless sense a lingering concern that the military served as the scapegoat of the war in Vietnam. I fail to share that concern. The military quite clearly did the job that the nation expected of it, and I am convinced that history will reflect more favorably upon the performance of the military than upon that of the politicians and policy makers. The American people can be proud that their military leaders scrupulously adhered to a basic tenet of our constitution prescribing civilian control of the military. As the soldier prays for peace he must be prepared to cope with the hardships of war and to bear its scars.

- Closing words, p. 424-425.

Quotes about Westmoreland

editA fine soldier and true friend is Westy. Modest, generous, tolerant and possessing a good sense of humor, Westy has made many friends. His executive ability, conscientiousness, high ideals, good judgement and common sense, and his fearless determination-(just glance at that chin!)-have well fitted him for the position he has held as leader of our class, and as First Captain of the Corps. Always busy, he has never been too busy to help a friend, or to actively support a worthy cause. Westy's enthusiastic and successful participation in many extracurricular activities rounds out a well-balanced and outstanding four years at West Point. ~ The Howitzer (1936)

Then she asked, "What do you think of the Supe?" "With all due respect, ma'am, I think he's a prick." Kitsy: "That's my husband." Pause. "Pardon me, ma'am, that's my morphine talking." ~ Lewis Sorley

- An opportunity to take part in a Veterans celebration in Springfield, Illinois, brought me together with Ambassador William E. Colby and General William C. Westmoreland. Upon hearing about my recent trips to Vietnam, they expressed an interest in starting some type of non-political, non-governmental organization to help bridge the gap between our two countries. I have great admiration for General and Mrs. Westmoreland. They continue to serve their country and the Vietnam-era veterans. They are always available to support Vietnam veterans and have attended hundreds of functions across America demonstrating their patriotism. When Ambassador Colby co-founded The Westmoreland Scholar Foundation and asked me to be the first executive director, I accepted without hesitation.

- Roger H.C. Donlon, in his book Beyond Nam Dong (1998), p. 218-219.

- General, I have a lot riding on you. I hope you don't pull a MacArthur on me.

- Lyndon B. Johnson, said to Westmoreland when the two men met in Honolulu in 1966. As quoted in The Truman-MacArthur Tug of War – A Lingering Aftermath (1993) by Stephen A. Danner, p. 14-15

- I have often reflected that General Abrams, who had worked so hard to make the South Vietnamese armed forces capable of defending their country, at least had been spared the agony of seeing the death of the Republic of Vietnam. Westmoreland, on the other hand, was not spared that trauma, but seems over the years since the war to have become a national scapegoat, blamed for everything that went wrong in Vietnam, large or small, regardless of whether he had even a remote connection with the matter. It is a singularly fair and unsupported judgement. Many scores of senior American officials, civilian and military, including the author, contributed to our Vietnam mistakes, most of which have been so judged in hindsight. The real "blame", of course, must be laid squarely on the Hanoi regime and the North Vietnamese people, who demonstrated to the world that they had the will to prevail. Although it is a small comfort to Westmoreland, history is replete with the examples of one native son's being singled out, rightly or wrongly, as the person responsible for a national disaster.

- Bruce Palmer, Jr., in his book The 25-Year War: America's Military Role in Vietnam (1984), p. 133-144

- Both Abrams and Westmoreland would have been judged as authentic military "heroes" at a different time in history. Both men were outstanding leaders in their own right and in their own way. They offered sharply contrasting examples of military leadership, something akin to the distinct differences between Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant of our Civil War period. They entered the United States Military Academy at the same time in 1932- Westmoreland from a distinguished South Carolina family, and Abrams from a simpler family background in Massachusetts- and graduated together with the Class of 1936. Whereas Westmoreland became the First Captain (the senior cadet in the corps) during their senior year, Abrams was a somewhat nondescript cadet whose major claim to fame was as a loud, boisterous guard on the second-string varsity football squad. Both rose to high rank through outstanding performance in combat command jobs in World War II and the Korean War, as well as through equally commendable work in various staff positions. But as leaders they were vastly different. Abrams was the bold, flamboyant charger who wanted to cut to the heart of the matter quickly and decisively, while Westmoreland was the more shrewdly calculating, prudent commander who chose the more conservative course. Faultlessly attired, Westmoreland constantly worried about his public image and assiduously courted the press. Abrams, on the other hand, usually looked rumpled, as though he might have slept in his uniform, and was indifferent about his appearance, acting as though he could care less about the press. The sharply differing results were startling; Abrams rarely receiving a bad press report, Westmoreland struggling to get a favorable one.

- Bruce Palmer, Jr., in his book The 25-Year War: America's Military Role in Vietnam (1984), p. 134

- We underestimated the willingness of these peasants to pay the price. We won every set piece battle. Westy believes that he never lost a battle. We had absolute military superiority, and they had absolute political superiority, which meant that we would kill 200 and they would replenish them the next day. We were fighting the birth rate of a nation.

- David Halberstam, as quoted in Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam (2011) by Lewis Sorley, p. 96.

- A fine soldier and true friend is Westy. Modest, generous, tolerant and possessing a good sense of humor, Westy has made many friends. His executive ability, conscientiousness, high ideals, good judgement and common sense, and his fearless determination-(just glance at that chin!)-have well fitted him for the position he has held as leader of our class, and as First Captain of the Corps. Always busy, he has never been too busy to help a friend, or to actively support a worthy cause. Westy's enthusiastic and successful participation in many extracurricular activities rounds out a well-balanced and outstanding four years at West Point.

- Description of Westmoreland in The Howitzer (1936), yearbook of the United States Military Academy, p. 216.

- In 1967, the problem of "ghost effectives" (unit commanders reporting imaginary soldiers to pocket their salaries) was so serious that, under American instigation, the ARVN Inspector General was instructed to inspect the effective forces of different units selected at random. One day, it was decided that the 15th Regiment of my division was to be inspected at Long Xuyen Province. Lt. Gen. Nguyen Van La, the Inspector General, was accompanied by a U.S. brigadier general acting as a liaison officer with the Vietnamese Joint General Staff. The purpose of the inspection was to determine whether the number of troops corresponded to the regiment's reported effective. The U.S. general, however, displaying supreme arrogance, made comments about the physical presentation of the regiment, which, by the way, had returned from an operation the day before. He pulled the soldiers' hair which, he commented, was too long or the uniforms, which, he said, missed a couple of buttons. He acted like a commander inspecting his troops in a parade, and as though General La and I were his subordinates or we did not exist at all. I took General La aside and suggested that the American general be advised that he had overstepped the boundary of his authority and decency, and that he should stop his uncalled-for behavior at once. A few months after that incident, Nyguyen Cao Ky told me during a meeting at IV Corps Headquarters at Can Tho, that General Westmoreland had informed him that I had become "anti-American."

- Lam Quang Thi, The Twenty-Five Year Century: A South Vietnamese General Remembers the Indochina War to the Fall of Saigon (2001), p. 170-171

- It was disturbing to see that General Westmoreland kept asking for additional troops without any clear objective. During the Korean War, Douglas MacArthur requested permission to cross the Yalu River to invade Manchuria. He was fired. General Westmoreland kept asking for new troops and didn't know what to do with them. He was later promoted to Army Chief of Staff. This was the sign of the times. It was unfortunate that we did not have generals in Viet Nam of MacArthur's caliber who knew what the objectives were and how to achieve them.

- Lam Quang Thi, The Twenty-Five Year Century: A South Vietnamese General Remembers the Indochina War to the Fall of Saigon (2001), p. 156

- General Westmoreland complained in his book A Soldier Reports about government officials in Washington trying to act as field marshals. But the situation became worse when journalists and academicians started to act similarly.

- Lam Quang Thi, The Twenty-Five Year Century: A South Vietnamese General Remembers the Indochina War to the Fall of Saigon (2001), p. 192

- It was ironic that President Nixon, in a memo released by the National Archives, complained that his commanders had played "how not to lose" that they had forgotten "how to win." To render justice to the generals, I agree with General Westmoreland that the U.S. needed to rethink its Viet Nam policies. It had to do away with the "status quo" and resolutely carry he war to the North. Although President Nixon later ordered B-52 runs on North Viet Nam, this move was not so much to win the war, but to induce the enemy to sit at the negotiation table.

- Lam Quang Thi, The Twenty-Five Year Century: A South Vietnamese General Remembers the Indochina War to the Fall of Saigon (2001), p. 246

- What, then, had we learned with our sacrifices in the Ia Drang Valley? We had learned something about fighting the North Vietnamese regulars- and something important about ourselves. We could stand against the finest light infantry troops in the world and hold our ground. General Westmoreland thought he had found the answer to the question of how to win this war: He would trade one American life for ten or twelve North Vietnamese lives, day after day, until Ho Chi Minh cried uncle. Westmoreland would learn, too late, that he was wrong; that the American people didn't see a kill ratio of 10-1 or even 20-1 as any kind of bargain.

- Harold G. "Hal" Moore, co-author of We Were Soldiers Once.. And Young (1992), p. 345

- Kitsy was widely liked and admired by the West Point community, where she involved herself in many aspects of post life. Cadet Mark Sheridan met her while he was hospitalized for repair of torn ligaments. "An incredibly beautiful and sweet woman appeared at my bedside," he recalled. She asked how he was doing and how he felt about West Point. "All my life," he said, "this is where I wanted to go and this is the school I wanted to graduate from." Then she asked, "What do you think of the Supe?" "With all due respect, ma'am, I think he's a prick." Kitsy: "That's my husband." Pause. "Pardon me, ma'am, that's my morphine talking."

- Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam (2012) by Lewis Sorley, p. 61.

- One reason for the failure of Johnson's Vietnam policy was the inherent unworkability of U.S. military strategy. The gradual escalation of the U.S. bombing campaign allowed the North Vietnamese sufficient time to disperse their population and resources and to develop an air defense system that would destroy a large number of U.S. aircraft. Moreover, the U.S. Army never developed a consistent strategy for stopping the infiltrations of regular North Vietnamese units and supplies into the South. General Westmoreland's search-and-destroy strategy was designed primarily to protect the cities of South Vietnam while killing as many Vietcong as possible. Westmoreland grossly miscalculated North Vietnam's willingness to suffer huge losses in manpower as well as its capacity to replace those losses. An estimated 200,000 North Vietnamese males reached draft age each year, far more than U.S. forces could kill. North Vietnam was able to sustain its war effort by drawing on both Soviet and Chinese military and economic assistance. With the Sino-Soviet split deeper than ever, even after Krushchev's demise, both communist powers tried to outdo each other in helping North Vietnam. Their combined assistance between 1965 and 1968 exceeded $2 billion, an amount that more than offset the losses North Vietnam suffered from U.S. bombing. In addition, between 1962 and 1968 approximately 300,000 Chinese soldiers went to North Vietnam, 4,000 of whom were killed. Though not participating in ground combat, they helped operate antiaircraft weapons and communications facilities.

- Ronald Powaski, The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917-1991 (1998), p. 157

- With no prospect of either a military or diplomatic end to the war, the carnage inevitably grew. By late 1967 the number of U.S. military personnel killed in action reached 13,500. Many Americans were wondering if the war was worth the mounting deaths that were so vividly displayed on the nightly news. Slowly, American public opinion turned against the administration. College students in particular became bitter opponents of the war. But the opposition to the conflict also increased in Congress, with Senators William Fulbright (Dem.-Ark.) and Wayne Morse (Rep.-Ore.) leading the attack, bringing to a standstill legislative progress on Johnson's cherished great society program. By 1967 growing demonstrations against the war and vicious personal criticism of the president had made Johnson a virtual prisoner in the White House. The increasing unpopularity of the war, however, did not sway Johnson from his goal of preserving a noncommunist South Vietnam. For the president in 1967, there was no acceptable alternative but a continuation of the war. Accordingly, in August 1967 he approved General Westmoreland's request for an additional 45,000-50,000 troops, but he imposed a new ceiling of 525,000 military personnel, a level that was not surpassed for the remainder of the war. In November 1967 Westmoreland assured Johnson that the United States was "turning the corner" in Vietnam.

- Ronald Powaski, The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917-1991 (1998), p. 160

- Then, much to the surprise of U.S. intelligence, the supposedly nearly beaten North Vietnamese and their Vietcong allies launched a major offensive against the cities of South Vietnam in February 1968. Coinciding with the Vietnamese Tet holiday, the communist forces attacked more than 100 towns and cities, including Saigon, where the grounds of the U.S. Embassy were penetrated, and Huế, the ancient capital of Vietnam, which the communists held for more than a month before they were driven out. While American and South Vietnamese forces were able to repel the communist onslaught, and inflict enormous losses on the enemy in the process, they also suffered heavy casualties. The Tet offensive was a significant military victory for the United States, but it was also a stunning psychological defeat. To most Americans, who had been subjected to repeated administration claims that the war was being won, it seemed incredible that the communists could mount such an impressive offensive.

- Ronald Powaski, The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917-1991 (1998), p. 160-161

- After Tet, with no end to the war in sight, a Gallup poll in March 1968 reported that a clear majority of "Middle America" had turned against the administration. The same poll showed that Johnson's approval rating had reached a new low of 30 percent. General Westmoreland seemed oblivious to the growing hostility of the American people and Congress toward the war. He insisted that the communists had been dealt a crippling blow during Tet and that the war could be won by launching new ground offensives against their bases in Laos, Cambodia, and North Vietnam, and by intensifying and expanding the bombing campaign, especially around Hanoi and Haiphong. To implement this strategy, Westmoreland requested an additional 206,000 troops.

- Ronald Powaski, The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917-1991 (1998), p. 161

- That summer of 1970, the Army War College issued a scathing report- commissioned by General William Westmoreland, who was now chief of staff- that explained a great deal of what we're seeing. Based on a confidential survey of 415 officers, the report blasted the Army for rewarding the wrong people. It described how the system had been subverted to condone selfish behavior and tolerate incompetent commanders who sacrificed their subordinates and distorted facts to get ahead. It criticized the Army's obsession with meaningless statistics and was especially damning on the subject of body counts in Vietnam. A young captain had told the investigators a sickening story: he'd been under so much pressure from headquarters to boost his numbers that he'd nearly gotten into a fistfight with a South Vietnamese officer over whose unit would take credit for various enemy body parts. Many officers admitted they had simply inflated their reports to placate headquarters.

- Norman Schwarzkopf, It Doesn't Take a Hero (1992), p. 178

- The Military Academy during Westmoreland's superintendency was still an all-male institution, as it would remain until 1976. Soon after that Westmoreland revealed his opposition to coeducation in an oral history interview. "I was aware that there would be political pressures," he acknowledged, "but I thought they would be resisted. I think the academies, the Department of the Army, and the Department of Defense got caught napping on this one and, in my opinion, if they had mounted a countercurrent against it, it was a matter that could have been defeated." He discussed it again during a 1980 appearance on a Larry King radio program. "Are you happy about that?" asked King, referring to the presence of women at West Point. "Actually, very frankly, I am not," Westmoreland told him. "I was against this as a matter of principle, but they're there now, and I must say I admire the performance of those who have been able to endure the curriculum and the rigors of the system." These views were consistent with Westmoreland's outlook while Superintendent. West Point's ice hockey coach learned about that one time when his daughter Mary Beth said to Westmoreland, "When I grow up I'm going to come to West Point." Westmoreland's reply was blunt: "Over my dead body!"

- Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam (2011) by Lewis Sorley, p. 63.

- An unfortunate flap marred Westmoreland's last full day as Superintendent. Apparently he had been returning from the tennis courts and two First Classmen who were sunning themselves did not see him, so they did not leap up and salute. Cadet Richard Chilcoat, soon to be appointed First Captain for the coming year, was then "King of Beasts", the senior cadet on the detail training new plebes. That night at 11:00 he got a call from Westmoreland, who said he wanted to address the detail the next morning. Chilcoat had everybody in ranks at 6:00AM, expecting a stirring departure speech. Instead Westmoreland, standing on the stoops of barracks, harangued them for fifteen minutes on their lack of discipline, lack of military courtesy, and so on. Then, remembered Chilcoat, "He stomped back to his quarters and, an hour later, drove away. This had a permanent, and negative, effect on the Class of 1964."

- Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam (2011) by Lewis Sorley, p. 64.

Westmoreland told him, "We're killing these people at a rate of 10 to 1." To that Hollings responded, "Westy, the American people don't care about the ten. They care about the one." ~ Lewis Sorley

- A very influential visitor, Senator "Fritz" Hollings from Westmoreland's home state of South Carolina, had warned him about relying on such ratios. Westmoreland told him, "We're killing these people at a rate of 10 to 1." To that Hollings responded, "Westy, the American people don't care about the ten. They care about the one."

- Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam (2011) by Lewis Sorley, p. 95.

- Only a few days after the Ia Drang, the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, was back at the division base camp at An Khe on a cold and rainy Thanksgiving. Lieutenant Colonel Robert McDade, the battalion commander, met a visiting Westmoreland near the mess hall and told him that everyone was just about ready to eat their Thanksgiving dinners. But Westmoreland told him, "Get them all together and let me talk to them." The troops had been issued a hot meal, real coffee instead of the powdered stuff that came with C-Rations, turkey, and the trimmings. They were walking back to their squad tents to enjoy this special repast when the order was given to assemble. "There stood General Westmoreland himself," said Sergeant John Setelin. "He made a speech there in the rain and while he talked we watched the rain turn that hot dinner into cold Mulligan stew. Who knew what the hell the man said? Who cared?"

- Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam (2011) by Lewis Sorley, p. 96.

- Westmoreland departed this life the evening of 18 July 2005 at the Episcopal retirement home where he and Kitsy then resided. He was ninety-one. The New York Times obituary referred to him as the officer "who failed to lead the United States forces to victory in Vietnam from 1964 to 1968 and then made himself the most prominent advocate for recognition of their sacrifices, spending the rest of his life paying tribute to his soldiers."

- Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam (2011) by Lewis Sorley, p. 300.

- On Saturday, 23 July 2005, Westmoreland was buried at West Point at a gravesite he had chosen when he was Superintendent there. It was an idyllic summer day, with a deep blue sky dotted with puffy white clouds, and hot. The provost marshal had anticipated throngs comparable to those on a football weekend. Thus military policemen spaced at intervals ringed the cemetery grounds, prepared to deal with traffic and crowds that never came.

- Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam (2011) by Lewis Sorley, p. 300.

- In later years Westmoreland, widely regarded as a general who lost his war, also lost his only run for political office, lost his libel suit, and lost his reputation. It was a sad ending for a man who for most of his life and career had led a charmed existence. In his final days, it could never be said that he'd been broken, for his still maintained the mien and demeanor of the glory days, much of the "look of eagles" his splendid countenance had always afforded him, the obvious expectation of being admired and courted by others. But, at least with family and, back in his native South Carolina, certain very old friends and some new admirers, elements of his youthful charm seem to have reemerged. Said his daughter Stevie, describing those last years, "every day we're seeing less and less General and more and more Daddy."

- Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam (2011) by Lewis Sorley, p. 303.