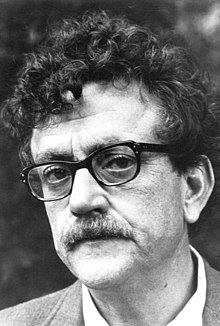

Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. (11 November 1922 – 11 April 2007) was an American novelist known for works blending satire, black comedy, and science fiction.

- See also:

- Harrison Bergeron (1961)

- Cat's Cradle (1963)

- Slaughterhouse-Five (1969)

- Who Am I This Time? (1982)

- Timequake (1997)

- 2081 (2009 film adaptation of "Harrison Bergeron")

Quotes

editVarious interviews

edit- I sometimes wondered what the use of any of the arts was. The best thing I could come up with was what I call the canary in the coal mine theory of the arts. This theory says that artists are useful to society because they are so sensitive. They are super-sensitive. They keel over like canaries in poison coal mines long before more robust types realize that there is any danger whatsoever.

- "Physicist, Purge Thyself" in the Chicago Tribune Magazine (22 June 1969)

- High school is closer to the core of the American experience than anything else I can think of.

- Introduction to Our Time Is Now: Notes From the High School Underground, John Birmingham, ed. (1970)

- I was taught in the sixth grade that we had a standing army of just over a hundred thousand men and that the generals had nothing to say about what was done in Washington. I was taught to be proud of that and to pity Europe for having more than a million men under arms and spending all their money on airplanes and tanks. I simply never unlearned junior civics. I still believe in it. I got a very good grade.

- As quoted by James Lundquist in Kurt Vonnegut (1971)

- All these people talk so eloquently about getting back to good old-fashioned values. Well, as an old poop I can remember back to when we had those old-fashioned values, and I say let's get back to the good old-fashioned First Amendment of the good old-fashioned Constitution of the United States—and to hell with the censors! Give me knowledge or give me death!

- As quoted in "An Interview with Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., Carey Horwitz, Library Journal, Apr. 15, 1973: 1131

- What should young people do with their lives today? Many things, obviously. But the most daring thing is to create stable communities in which the terrible disease of loneliness can be cured.

- My brother got his doctorate in 1938, I think. If he had gone to work in Germany after that, he would have been helping to make Hitler's dreams come true. If he had gone to work in Italy, he would have been helping to make Mussolini's dreams come true. If he had gone to work in Japan, he would have been helping to make Tojo's dreams come true. If he had gone to work in the Soviet Union, he would have been helping to make Stalin's dreams come true. He went to work for a bottle manufacturer in Butler, Pennsylvania, instead. It can make quite a difference not just to you but to humanity: the sort of boss you choose, whose dreams you help come true.

Hitler dreamed of killing Jews, Gypsies, Slavs, homosexuals, Communists, Jehovah's Witnesses, mental defectives, believers in democracy, and so on, in industrial quantities. It would have remained only a dream if it hadn't been for chemists as well educated as my brother, who supplied Hitler's executioners with the cyanide gas known as Zyklon B. It would have remained only a dream if architects and engineers as capable as my father and grandfather hadn't designed extermination camps — the fences, the towers, the barracks, the railroad sidings, and the gas chambers and crematoria — for maximum ease of operation and efficiency.- Speech at MIT (1985), referring to his brother Bernard Vonnegut, and the choices available to scientists and the intelligent, to serve humanity, or to betray it, as published in Fates Worse Than Death (1991), Ch. 12

- Well, I've worried some about, you know, why write books … why are we teaching people to write books when presidents and senators do not read them, and generals do not read them. And it's been the university experience that taught me that there is a very good reason, that you catch people before they become generals and presidents and so forth and you poison their minds with … humanity, and however you want to poison their minds, it's presumably to encourage them to make a better world.

- "A Talk with Kurt Vonnegut. Jr." by Robert Scholes in The Vonnegut Statement (1973) edited by Jerome Klinkowitz and John Somer October 1966), later published in Conversations With Kurt Vonnegut (1988), p. 123

- I was taught that the human brain was the crowning glory of evolution so far, but I think it’s a very poor scheme for survival.

- As quoted in The Observer [London] (27 December 1987)

- 1. Find a subject you care about.

2. Do not ramble, though.

3. Keep it simple.

4. Have the guts to cut.

5. Sound like yourself.

6. Say what you mean to say.

7. Pity the readers.- As quoted in Science Fictionisms (1995), compiled by William Rotsler

- Literature is idiosyncratic arrangements in horizontal lines in only twenty-six symbols, ten arabic numbers, and about eight punctuation marks.

- Public conversation with Lee Stringer, in Like Shaking Hands With God (1999)

- What television does is rent us friends and relatives who are quite satisfactory. The child watching TV loves these people, you know -- they're in color, and they're talking to the child. Why wouldn't a child relate to these people? And you know, if you can't sleep at 3 o'clock in the morning, you can turn on a switch, and there are your friends and relatives, and they obviously like you. And they're charming. Who wouldn't want Peter Jennings for a relative? This is quite something, to rent artificial friends and relatives right inside the house.

- Interviewed by Frank Houston, "The Salon Interview: Kurt Vonnegut", Salon (October 8, 1999)

- You learn about life by the accidents you have, over and over again, and your father is always in your head when that stuff happens. Writing, most of the time, for most people, is an accident and your father is there for that, too. You know, I taught writing for a while and whenever somebody would tell me they were going to write about their dad, I would tell them they might as well go write about killing puppies because neither story was going to work. It just doesn't work. Your father won't let it happen.

- Interviewed by J. Rentilly, "The Best Jokes Are Dangerous", McSweeny's (September 2002)

- The telling of jokes is an art of its own, and it always rises from some emotional threat. The best jokes are dangerous, and dangerous because they are in some way truthful.

- Interviewed by J. Rentilly, "The Best Jokes Are Dangerous", McSweeny's (September 2002)

- One of the great American tragedies is to have participated in a just war. It's been possible for politicians and movie-makers to encourage us we're always good guys. The Second World War absolutely had to be fought. I wouldn't have missed it for the world. But we never talk about the people we kill. This is never spoken of.

- Interviewed by Roger Friedman, "God Bless You, Mr. Vonnegut", FoxNews.com (11 November 2002)

- I urge you to please notice when you are happy, and exclaim or murmur or think at some point, "If this isn't nice, I don't know what is."

- "Knowing What's Nice", an essay from In These Times (2003)

- During the Vietnam War, which lasted longer than any war we've ever been in -- and which we lost -- every respectable artist in this country was against the war. It was like a laser beam. We were all aimed in the same direction. The power of this weapon turns out to be that of a custard pie dropped from a stepladder six feet high.

- "Vonnegut at 80" Interview with David Hoppe Alternet (2003)

- We're terrible animals. I think that the Earth's immune system is trying to get rid of us, as well it should.

- On humans, interviewed by Jon Stewart, The Daily Show (13 September 2005)

- I have wanted to give Iraq a lesson in democracy — because we’re experienced with it, you know. And, in democracy, after a hundred years, you have to let your slaves go. And, after a hundred and fifty years, you have to let your women vote. And, at the beginning of democracy, is that quite a bit of genocide and ethnic cleansing is quite okay. And that’s what’s going on now.

- Interviewed by Jon Stewart on The Daily Show (13 September 2005)

- I do feel that evolution is being controlled by some sort of divine engineer. I can't help thinking that. And this engineer knows exactly what he or she is doing and why, and where evolution is headed. That’s why we’ve got giraffes and hippopotami and the clap.

- On evolution vs. "intelligent design", interviewed by Jon Stewart, The Daily Show (13 September 2005)

- [When Vonnegut tells his wife he's going out to buy an envelope] Oh, she says, well, you're not a poor man. You know, why don't you go online and buy a hundred envelopes and put them in the closet? And so I pretend not to hear her. And go out to get an envelope because I'm going to have a hell of a good time in the process of buying one envelope. I meet a lot of people. And, see some great looking babes. And a fire engine goes by. And I give them the thumbs up. And, and ask a woman what kind of dog that is. And, and I don't know. The moral of the story is, is we're here on Earth to fart around. And, of course, the computers will do us out of that. And, what the computer people don't realize, or they don't care, is we're dancing animals. You know, we love to move around. And, we're not supposed to dance at all anymore.

- Where is home? I've wondered where home is, and I realized, it's not Mars or someplace like that, it's Indianapolis when I was nine years old. I had a brother and a sister, a cat and a dog, and a mother and a father and uncles and aunts. And there's no way I can get there again.

- As quoted in "The World according to Kurt" in Globe and Mail [Toronto] (11 October 2005)

- No matter how corrupt, greedy, and heartless our government, our corporations, our media, and our religious and charitable institutions may become, the music will still be wonderful. If I should ever die, God forbid, let this be my epitaph:

THE ONLY PROOF HE NEEDED

FOR THE EXISTENCE OF GOD

WAS MUSIC.

Now, during our catastrophically idiotic war in Vietnam, the music kept getting better and better and better. We lost that war, by the way. Order couldn’t be restored in Indochina until the people kicked us out. That war only made billionaires out of millionaires. Today’s war is making trillionaires out of billionaires. Now I call that progress.

- Well, I just want to say that George W. Bush is the syphilis president.

- As quoted in "Kurt Vonnegut's 'Stardust Memory'", Harvey Wasserman, The Free Press (4 March 2006)

- The only difference between Bush and Hitler is that Hitler was elected.

- As quoted in "Kurt Vonnegut's 'Stardust Memory'" by Harvey Wasserman in The Free Press (4 March 2006); in actuality, Hitler also wasn't elected by a clear majority vote. Although the Nazi Party was elected to the largest number of seats in the Reichstag, it did not have a majority, and could only form a government through a coalition. Eventually, Hitler was appointed as Chancellor by President Paul von Hindenburg, and used that position as leverage to gain dictatorial powers.

- I don't think there would be many jokes, if there weren't constant frustration and fear and so forth. It's a response to bad troubles like crime.

- Interview Public Radio International (October 2006)

- People hate it when they're tickled because laughter is not pleasant, if it goes on too long. I think it's a desperate sort of convulsion in desperate circumstances, which helps a little.

- Interview Public Radio International (October 2006)

- My theory is that all women have hydrofluoric acid bottled up inside.

- On difficulties with women, as quoted in "Kurt Vonnegut, Writer of Classics of the American Counterculture, Dies at 84" by Dinitia Smith in The New York Times (11 April 2007)

Player Piano (1952)

edit- All page numbers from the mass market paperback edition published by Avon (Bard Books)

- During the war, in hundreds of Iliums over America, managers and engineers learned to get along without their men and women, who went to fight. It was the miracle that won the war — production with almost no manpower. In the patois of the north side of the river, it was the know-how that won the war. Democracy owed its life to know-how.

- Chapter 1 (p. 9)

- Anita had the mechanics of marriage down pat, even to the subtlest conventions. If her approach was disturbingly rational, systematic, she was thorough enough to turn out a credible counterfeit of warmth.

- Chapter 1 (p. 25)

- It was an appalling thought, to be so well-integrated into the machinery of society and history as to be able to move in only one plane, and along one line.

- Chapter 4 (p. 41)

- When Paul thought about his effortless rise in the hierarchy, he sometimes, as now, felt sheepish, like a charlatan. He could handle his assignments all right, but he didn’t have what his father had, what Kroner had, what Shepherd had, what so many had: the sense of spiritual importance in what they were doing; the ability to be moved emotionally, almost like a lover, by the great omnipresent and omniscient spook, the corporate personality. In short, what Paul missed was what made his father aggressive and great: the capacity to really give a damn.

- Chapter 6 (pp. 66-67)

- "You think I'm insane?" said Finnerty. Apparently he wanted more of a reaction than Paul had given him.

"You're still in touch. I guess that's the test."

"Barely — barely."

"A psychiatrist could help. There's a good man in Albany."

Finnerty shook his head. "He'd pull me back into the center, and I want to stay as close to the edge as I can without going over. Out on the edge you see all kinds of things you can't see from the center." He nodded, "Big, undreamed-of things — the people on the edge see them first."- Chapter 9 (p. 86)

- I figured things would be better in Washington, that I'd find a lot of people I admired and belonged with. Washington is worse, Paul—Ilium to the tenth power. Stupid, arrogant, self-congratulatory, unimaginative, humorless men. And the women, Paul—the dull wives feeding on the power and glory of their husbands.

- Chapter 9 (p. 88)

- You know, in a way I wish I hadn’t met you two. It’s much more convenient to think of the opposition as a nice homogeneous, dead-wrong mass. Now I've got to muddy my thinking with exceptions.

- Chapter 9 (p. 91)

- These displaced people need something, and the clergy can’t give it to them—or it’s impossible for them to take what the clergy offers. The clergy says it’s enough, and so does the Bible. The people say it isn’t enough, and I suspect they’re right.

- Chapter 9 (p. 92)

- "Strange business," said Lasher. "This crusading spirit of the managers and engineers, the idea of designing and manufacturing and distributing being sort of a holy war: all that folklore was cooked up by public relations and advertising men hired by managers and engineers to make big business popular in the old days, which it certainly wasn't in the beginning. Now, the engineers and managers believe with all their hearts the glorious things their forebears hired people to say about them. Yesterday's snow job becomes today's sermon."

- Chapter 9 (p. 93)

- Doctor Paul Proteus, son of a successful man, himself rich with prospects of being richer, counted his material blessings. He found that he was in excellent shape to afford integrity.

- Chapter 13 (p. 132)

- In order to get what we've got, Anita, we have, in effect, traded these people out of what was the most important thing on earth to them — the feeling of being needed and useful, the foundation of self-respect.

- Chapter 18 (p. 169)

- The band at the far end of the hall, amplified to the din of an elephant charge, smashed and hewed at the tune as though in a holy war against silence.

- Chapter 19 (p. 188)

- This silly playlet seemed to satisfy them completely as a picture of what they were doing, why they were doing it, and who was against them, and why some people were against them. It was a beautifully simple picture these procession leaders had. It was as though a navigator, in order to free his mind of worries, had erased all the reefs from his maps.

- Chapter 21 (p. 212)

- Everybody's shaking in his boots, so don't be bluffed.

- Chapter 22 (p. 219)

- Almost nobody's competent, Paul. It's enough to make you cry to see how bad most people are at their jobs. If you can do a half-assed job of anything, you're a one-eyed man in the kingdom of the blind.

- Chapter 22 (p. 219)

- And as Paul said these things to himself, a wave of sadness washed over them as though they’d been written in sand. He was understanding now that no man could live without roots—roots in a patch of desert, a red clay field, a mountain slope, a rocky coast, a city street. In black loan, in mud or sand or rock or asphalt or carpet, every man had his roots down deep—in home.

- Chapter 23 (p. 227)

- “This husband of yours, he’d rather have his wife a— Rather, have her—” Halyard cleared his throat— “than go into public relations?”

“I’m proud to say,” said the girl, “that he’s one of the few men on earth with a little self-respect left.”- Chapter 24 (p. 234)

- Paul wondered at what thorough believers in mechanization most Americans were, even when their lives had been badly damaged by mechanization.

- Chapter 26 (p. 241)

- “Why are you quitting?”

“Sick of my job.”

“Because what you were doing was morally bad?” suggested the voice.

“Because it wasn’t getting anybody anywhere. Because it was getting everybody nowhere.”

“Because it was evil?” insisted the voice.

“Because it was pointless.”- Chapter 29 (p. 271)

- Here it was again, the most ancient of roadforks, one that Paul had glimpsed before, in Kroner's study, months ago. The choice of one course or the other had nothing to do with machines, hierarchies, economics, love, age. It was a purely internal matter. Every child older than six knew the fork, and knew what the good guys did here, and what the bad guys did here. The fork was a familiar one in folk tales the world over, and the good guys and the bad guys, whether in chaps, breechclouts, serapes, leopardskins, or banker's gray pinstripes, all separated here.

Bad guys turned informer. Good guys didn't — no matter when, no matter what.- Chapter 31 (p. 293)

- And a step backward, after making a wrong turn, is a step in the right direction.

- Chapter 32 (p. 295)

- "Things don't stay the way they are," said Finnerty. "It's too entertaining to try to change them."

- Chapter 34 (p. 313)

- “If only it weren’t for the people, the goddamned people,” said Finnerty, “always getting tangled up in the machinery. If it weren’t for them, earth would be an engineer’s paradise.”

- Chapter 34

The Sirens of Titan (1959)

edit- All page numbers are from the mass market paperback edition published by Dell, ninth printing (October 1971)

- Nominated for the 1960 Hugo Award

- Every passing hour brings the Solar System forty-three thousand miles closer to Globular Cluster M13 in Hercules—and still there are some misfits who insist that there is no such thing as progress.

- Opening epigram

- Mankind, ignorant of the truths that lie withing every human being, looked outward—pushed ever outward. What mankind hoped to learn in its outward push was who was actually in charge of all creation, and what all creation was all about.

- Chapter 1 “Between Timid and Timbuktu” (p. 7)

- These unhappy agents found what had already been found in abundance on Earth—a nightmare of meaningless without end. The bounties of space, of infinite outwardness, were three: empty heroics, low comedy, and pointless death.

Outwardness lost, at last, its imagined attractions.

Only inwardness remained to be explored.

Only the human soul remained terra incognita.

This was the beginning of goodness and wisdom.- Chapter 1 “Between Timid and Timbuktu” (p. 8)

- He held up his watch to sunlight, letting it drink in the wherewithal that was to solar watches what money was to Earth men.

- Chapter 1 “Between Timid and Timbuktu” (p. 17)

- He ransacked his memory like a thief going through another man’s billfold.

- Chapter 1 “Between Timid and Timbuktu” (p. 22)

- “I tell you, Mr. Constant,” he said genially, “it’s a thankless job, telling people it’s a hard, hard Universe they’re in.”

- Chapter 1 “Between Timid and Timbuktu” (p. 25)

- “I liked him very much,” said Constant.

“The insane, on occasion, are not without their charms,” said Beatrice.- Chapter 1 “Between Timid and Timbuktu” (p. 41)

- The riot, then, was an exercise in science and theology—a seeking after clues by the living as to what life was all about.

- Chapter 1 “Between Timid and Timbuktu” (p. 44)

- Sometimes I think it is a great mistake to have matter that can think and feel. It complains so. By the same token, though, I suppose that boulders and mountains and moons could be accused of being a little too phlegmatic.

- Chapter 2 “Cheers in the Wirehouse” (p. 45; epigram)

- “The hell with the human race!” said Beatrice.

“You’re a member of it, you know,” said Rumfoord.

“Then I’d like to put in for a transfer to the chimpanzees!” said Beatrice. “No chimpanzee husband would stand by while his wife lost all her coconuts.”- Chapter 2 “Cheers in the Wirehouse” (p. 52)

- It is always pitiful when any human being falls into a condition hardly more respectable than that of an animal. How much more pitiful it is when the person who falls has had all the advantages!

- Chapter 2 “Cheers in the Wirehouse” (p. 52)

- Rumfoord had known that Constant would try to debase the picture by using it in commerce. Constant’s father had done a similar thing when he found he could not buy Leonardo’s “Mona Lisa” at any price. The old man had punished Mona Lisa by having her used in an advertising campaign for suppositories. It was the free-enterprise way of handling beauty that threatened to get the upper hand.

- Chapter 2 “Cheers in the Wirehouse” (p. 56)

- “Look,” said Rumfoord, “life for a punctual person is like a roller coaster.” He turned to shiver his hands in her face. “All kinds of things are going to happen to you! Sure,” he said, “I can see the whole roller coaster you’re on. And sure—I could give you a piece of paper that would tell you about every dip and turn, warn you about every bogeyman that was going to pop out at you in the tunnels. But that wouldn’t help you any.”

“I don’t see why not,” said Beatrice.

“Because you’d still have to take the roller-coaster ride,” said Rumfoord. “I didn’t design the roller coaster, I don’t own it, and I don’t say who rides and who doesn’t. I just know what it’s shaped like.- Chapter 2 “Cheers in the Wirehouse” (pp. 57-58)

- Son—they say there isn’t any royalty in this country, but do you want me to tell you how to be king of the United States of America? Just fall through the hole in a privy and come out smelling like a rose.

- Chapter 3 “United Hotcake Preferred” (p. 65; epigram)

- “You go up to a man, and you say, ‘How are things going, Joe?’ And he says, ‘Oh fine, fine—couldn’t be better.’ And you look into his eyes, and you see things really couldn’t be much worse. When you get right down to it, everybody’s having a perfectly lousy time of it, and I mean everybody. And the hell of it is, nothing seems to help much.”

- Chapter 3 “United Hotcake Preferred” (p. 69)

- There is a riddle about a man who is locked in a room with nothing but a bed and a calendar, and the question is: How does he survive?

The answer is: He eats dates from the calendar and drinks water from the springs of the bed.- Chapter 3 “United Hotcake Preferred” (p. 72)

- It was a marvelous engine for doing violence to the spirit of thousands of laws without actually running afoul of so much as a city ordinance.

- Chapter 3 “United Hotcake Preferred” (p. 78)

- All the things you are are going to be sued and sued successfully. And, while the litigants may not be able to get blood from turnips, they can certainly ruin the turnips in the process of trying.

- Chapter 3 “United Hotcake Preferred” (p. 85)

- He was too good a soldier to go around asking questions, trying to round out his knowledge.

A soldier’s knowledge wasn’t supposed to be round.- Chapter 5 “Letter From an Unknown Hero” (p. 120)

- The big trouble with dumb bastards is that they are too dumb to believe there is such a thing as being smart.

- Chapter 5 “Letter From an Unknown Hero” (p. 127)

- The lieutenant-colonel realized for the first time what most people never realize about themselves—that he was not only a victim of outrageous fortune, but one of outrageous fortune’s cruelest agents as well.

- Chapter 6 “A Deserter in Time of War” (p. 162)

- There is no reason why good cannot triumph as often as evil. The triumph of anything is a matter of organization. If there are such things as angels, I hope that they are organized along the lines of the Mafia.

- Chapter 7 “Victory” (p. 165; epigram)

- “Any man who would change the World in a significant way must have showmanship, a genial willingness to shed other people’s blood, and a plausible new religion to introduce during the brief period of repentance and horror that usually follows bloodshed.

“Every failure of Earthling leadership has been traceable to a lack on the part of the leader,” says Rumfoord, “of at least one of these three things.”- Chapter 7 “Victory” (p. 174)

- “The name of the new religion,” said Rumfoord, “is The Church of God the Utterly Indifferent.

“The flag of that church will be blue and gold,” said Rumfoord. “These words will be written on that flag in gold letters on a blue field: Take Care of the People, and God Almighty Will Take Care of Himself.

“The two chief teachings of this religion are these,” said Rumfoord: “Puny man can do nothing at all to help or please God Almighty, and Luck is not the hand of God.”- Chapter 7 “Victory” (p. 180)

- “During my next visit with you, fellow-believers,” he said, “I shall tell you a parable about people who do things that they think God Almighty wants done. In the meanwhile, you would do well, for background on this parable, to read everything that you can lay your hands on about the Spanish Inquisition.”

- Chapter 7 “Victory” (p. 181)

- “O Lord Most High, Creator of the Cosmos, Spinner of Galaxies, Soul of Electromagnetic Waves, Inhaler and Exhaler of Inconceivable Vacuum, Spitter of Fire and Rock, Trifler with Millennia—what could we do for Thee that Thou couldst not do for Thyself one octillion times better? Nothing. What could we do or say that could possibly interest Thee? Nothing. Oh, Mankind, rejoice in the apathy of our Creator, for it makes us free and truthful and dignified at last. No longer can a fool like Malachi Constant point to a ridiculous accident of good luck and say, ‘Somebody up there likes me.’ And no longer can a tyrant say, ‘God wants this or that to happen, and anybody who doesn’t help this or that to happen is against God.’ O Lord Most High, what a glorious weapon is Thy Apathy, for we have unsheathed it, have thrust and slashed mightily with it, and the claptrap that has so often enslaved us or driven us into the madhouse lies slain!”

- Chapter 10 “An Age of Miracles” (p. 215; epigram)

- There was not a country in the world that had not fought a battle in the war of all Earth against the invaders from Mars.

All was forgiven.

All living things were brothers, and all dead things were even more so.- Chapter 10 “An Age of Miracles” (p. 216)

- “Thank God!” said Unk.

Redwine raised his eyebrows quizzically. “Why?” he said.

“Pardon me?” said Unk.

“Why thank God?” said Redwine. “He doesn’t care what happens to you. He didn’t go to any trouble to get you here safe and sound, any more than He would go to the trouble to kill you.”- Chapter 10 “An Age of Miracles” (p. 226)

- I can think of no more stirring symbol of man’s humanity to man than a fire engine.

- Chapter 10 “An Age of Miracles” (p. 242)

- I was a victim of a series of accidents, as are we all.

- Chapter 11 “We Hate Malachi Constant Because...” (p. 253)

- His poor soul was flooded with pleasure as he realized that one friend was all that a man needed in order to be well-supplied with friendship.

- Chapter 11 “We Hate Malachi Constant Because...” (p. 259)

- It may surprise you to learn that I take a certain pride, no matter how foolishly mistaken that pride may be, in making my own decisions for my own reasons.

- Chapter 12 “The Gentleman from Tralfamadore” (p. 285)

- “As far as I’m concerned,” said Constant, “the Universe is a junk yard, with everything in it overpriced. I am through poking around in the junk heaps, looking for bargains. Every so-called bargain,” said Constant, “has been connected by fine wires to a dynamite bouquet.”

- Chapter 12 “The Gentleman from Tralfamadore” (p. 290)

- It was in the nature of truly effective good-luck pieces that human beings never really owned them.

- Chapter 12 “The Gentleman from Tralfamadore” (p. 301)

- The controls were anything but a hunch-player’s delight in a Universe composed of one-trillionth part matter to one decillion parts black velvet futility.

- Epilogue “Reunion with Stony” (p. 303)

- “The worst thing that could possibly happen to anybody,” she said, “would be to not be used for anything by anybody.” ... “Thank you for using me,” she said to Constant, “even though I didn’t want to be used by anybody.”

- Epilogue “Reunion with Stony” (pp. 310-311)

- “I would say, ‘Is there anything I can do?’—but Skip once told me that that was the most hateful and stupid expression in the English language.”

- Epilogue “Reunion with Stony” (p. 313)

- “You finally fell in love, I see,” said Salo.

“Only an Earthling year ago,” said Constant. “It took us that long to realize that a purpose of human life, no matter who is controlling it, is to love whoever is around to be loved.- Epilogue “Reunion with Stony” (p. 313)

Mother Night (1961)

edit- We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.

- Introduction (1966)

- Sometimes misquoted as: Be careful what you pretend to be because you are what you pretend to be.

- And the city was lovely, highly ornamented, like Paris, and untouched by war. It was supposedly an “open” city, not to be attacked since there were no troop concentrations or war industries there. But high explosives were dropped on Dresden by American and British planes on the night of February 13, 1945, just about twenty-one years ago, as I now write. There were no particular targets for the bombs. The hope was that they would create a lot of kindling and drive firemen underground. And then tens of thousands of tiny incendiaries were scattered over the kindling, like seeds on freshly turned loam. More bombs were dropped to keep firemen in their holes, and all the little fires grew, joined one another, became one apocalyptic flame. Hey presto: fire storm. It was the largest massacre in European history, by the way. … Everything was gone but the cellars where 135,000 Hansels and Gretels had been baked like gingerbread men.

- Introduction (1966)

- If I'd been born in Germany, I suppose I would have been a Nazi, bopping Jews and gypsies and Poles around, leaving boots sticking out of snowbanks, warming myself with my secretly virtuous insides. So it goes.

- Introduction (1966)

- When you're dead you're dead.

- Introduction (1966)

- Here lies Howard Campbell’s essence,

Freed from his body’s noisome nuisance.

His body, empty, prowls the earth,

Earning what a body’s worth.

If his body and his essence remain apart,

Burn his body, but spare this, his heart.

- "All people are insane," he said. "They will do anything at any time, and God help anybody who looks for reasons."

- There are plenty of good reasons for fighting," I said, "but no good reason ever to hate without reservation, to imagine that God Almighty Himself hates with you, too. Where's evil? It's that large part of every man that wants to hate without limit, that wants to hate with God on its side. It’s that part of every man that finds all kinds of ugliness so attractive.

- Say what you will about the sweet miracle of unquestioning faith, I consider a capacity for it terrifying and absolutely vile.

- "I had hoped, as a broadcaster, to be merely ludicrous, but this is a hard world to be ludicrous in, with so many human beings so reluctant to laugh, so incapable of thought , so eager to believe and snarl and hate. So many people wanted to believe me!"

- "You hate America, don't you?" she said.

"That would be as silly as loving it," I said. "It's impossible for me to get emotional about it, because real estate doesn't interest me. It's no doubt a great flaw in my personality, but I can't think in terms of boundaries. Those imaginary lines are as unreal to me as elves and pixies. I can't believe that they mark the end or the beginning of anything of real concern to the human soul. Virtues and vices, pleasures and pains cross boundaries at will."

- Drawn crudely in the dust of three window-panes were a swastika, a hammer and sickle, and the Stars and Stripes. I had drawn the three symbols weeks before, at the conclusion of an argument about patriotism with Kraft. I had given a hearty cheer for each symbol, demonstrating to Kraft the meaning of patriotism to, respectively, a Nazi, a Communist, and an American. "Hooray, hooray, hooray," I'd said.

- What froze me was the fact that I had absolutely no reason to move in any direction. What had made me move through so many dead and pointless years was curiosity. Now even that flickered out.

- Generally speaking, espionage offers each spy an opportunity to go crazy in a way he finds irresistible.

Cat's Cradle (1963)

edit- Full title: Cat's Cradle These are just a sample for more from this work see: Cat's Cradle

- We Bokonists believe that humanity is organized into teams, teams that do God's Will without ever discovering what they are doing. Such a team is called a karass by Bokonon "If you find your life tangled up with somebody else's life for no very logical reasons," writes Bokonon, "that person may be a member of your karass." At another point in The Books of Bokonon he tells us, "Man created the checkerboard; God created the karass." By that he means that a karass ignores national, institutional, occupational, familial, and class boundaries. It is as free form as an amoeba.

- Busy, busy, busy.

- Someday, someday, this crazy world will have to end,

And our God will take things back that He to us did lend.

And if, on that sad day, you want to scold our God,

Why go right ahead and scold Him. He'll just smile and nod.

- Tiger got to hunt, bird got to fly;

Man got to sit and wonder 'why, why, why?'

Tiger got to sleep, bird got to land;

Man got to tell himself he understand.

- Beware of the man who works hard to learn something, learns it, and finds himself no wiser than before.

- Chapter 124: Frank's Ant Farm

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965)

edit- Full title: God Bless You, Mr Rosewater, or Pearls Before Swine

- Thus did a handful of rapacious citizens come to control all that was worth controlling in America. Thus was the savage and stupid and entirely inappropriate and unnecessary and humorless American class system created. Honest, industrious, peaceful citizens were classed as bloodsuckers, if they asked to be paid a living wage. And they saw that praise was reserved henceforth for those who devised means of getting paid enormously for committing crimes against which no laws had been passed. Thus the American dream turned belly up, turned green, bobbed to the scummy surface of cupidity unlimited, filled with gas, went bang in the noonday sun.

- I love you sons of bitches. You’re all I read any more. You're the only ones who’ll talk all about the really terrific changes going on, the only ones crazy enough to know that life is a space voyage, and not a short one, either, but one that’ll last for billions of years. You’re the only ones with guts enough to really care about the future, who really notice what machines do to us, what wars do to us, what cities do to us, what big, simple ideas do to us, what tremendous misunderstanding, mistakes, accidents, catastrophes do to us. You're the only ones zany enough to agonize over time and distance without limit, over mysteries that will never die, over the fact that we are right now determining whether the space voyage for the next billion years or so is going to be Heaven or Hell.

- "Eliot Rosewater" to a group of science fiction writers

- We few, we happy few, we band of brothers — joined in the serious business of keeping our food, shelter, clothing and loved ones from combining with oxygen.

- "Eliot Rosewater" to a group of volunteer firemen.

- "You must all take instructions from me!" the conscience shrieks, in effect, to all the other mental processes. The other processes try it for a while, note that the conscience is unappeased, that it continues to shriek, and they note, too, that the outside world has not been even microscopically improved by the unselfish acts the conscience has demanded. They rebel at last. They pitch the tyrannous conscience down an oubliette, weld shut the manhole cover of that dark dungeon. They can hear the conscience no more. In the sweet silence, the mental processes look about for a new leader, and the leader most prompt to appear whenever the conscience is stilled, Enlightened Self-interest, does appear. Enlightened Self-interest gives them a flag, which they adore on sight. It is essentially the black and white Jolly Roger, with these words written beneath the skull and crossbones, 'The hell with you, Jack, I've got mine!"

- Like all real heroes, Charley had a fatal flaw. He refused to believe that he had gonorrhea, whereas the truth was that he did.

- On Charley Warmergran, the Fire Chief of Rosewater.

- He alienated his friends in the sciences by thanking them extravagantly for scientific advances he had read about in the recent newspapers and magazines, by assuring them, with a perfectly straight face, that life was getting better and better, thanks to scientific thinking.

- Concerning Eliot Rosewater.

- A sum of money is a leading character in this tale about people, just as a sum of honey might properly be a leading character in a tale about bees.

- Opening line of novel.

- Hello, babies. Welcome to Earth. It's hot in the summer and cold in the winter. It's round and wet and crowded. At the outside, babies, you've got about a hundred years here. There's only one rule that I know of, babies — "God damn it, you've got to be kind."

- We don't piss in your ashtrays,

So please don't throw cigarettes in our urinals.- Eliot Rosewater's favorite poem, from the wall of the men's room at the Log Cabin Inn.

Welcome to the Monkey House (1968)

edit- A collection of previously published short stories

- Page numbers from the mass market paperback edition, published by Dell, catalogue# 9478, 26th printing (December 1975)

- See Kurt Vonnegut's Internet Science Fiction Database page for original publication details

- The public health authorities never mention the main reason many Americans have for smoking heavily, which is that smoking is a fairly sure, fairly honorable form of suicide.

- Preface (p. xi)

- The village would never accept it. It has a policy of never accepting anything. As a happy consequence, it changes about as fast as the rules of chess.

- Where I Live (p. 3)

- The year was 2081, and everybody was finally equal. They weren’t only equal before God and the law. They were equal every which way. Nobody was smarter than anybody else. Nobody was better looking than anybody else. Nobody was stronger or quicker than anybody else. All this equality was due to the 211th, 212th, and 213th Amendments to the Constitution, and to the unceasing vigilance of agents of the United States Handicapper General.

- Harrison Bergeron (p. 7)

- It was then that Diana Moon Glampers, the Handicapper General, came into the studio with a double-barreled ten-gauge shotgun. She fired twice, and the Emperor and the Empress were dead before they hit the floor.

- Harrison Bergeron (p. 13)

- “The world can't afford sex anymore.”

“Of course it can afford sex,” said Billy. “All it can't afford anymore is reproduction.”

“Then why the laws?”

“They’re bad laws,” said Billy. “If you go back through history, you'll find that the people who have been most eager to rule, to make the laws, to enforce the laws and to tell everybody exactly how God Almighty wants things here on earth—those people have forgiven themselves and their friends for anything and everything. But they have been absolutely disgusted and terrified by the natural sexuality of common men and women.”- Welcome to the Monkey House (pp. 45-46)

- He faced the problem that complicates the lives of cannibals—namely: that a single victim cannot be used over and over.

- Tom Edison’s Shaggy Dog (p. 104)

- He had only two moods: one suspicious and self-pitying, the other arrogant and boastful. The first mood applied when he was losing money. The second mood applied when he was making it.

- The Kid Nobody Could Handle (p. 253)

Slaughterhouse-Five (1969)

edit- Full title: Slaughterhouse-Five, Or The Children's Crusade : A Duty-dance with Death These are just a few samples, for more from this work see Slaughterhouse-Five

- So it goes.

- I have this disease late at night sometimes, involving alcohol and the telephone. I get drunk, and I drive my wife away with a breath like mustard gas and roses. And then, speaking gravely and elegantly into the telephone, I ask the telephone operators to connect me with this friend or that one, from whom I have not heard in years.

- The most important thing I learned on Tralfamadore was that when a person dies he only appears to die. He is still very much alive in the past, so it is very silly for people to cry at his funeral. All moments, past, present and future, always have existed, always will exist. The Tralfamadorians can look at all the different moments just that way we can look at a stretch of the Rocky Mountains, for instance. They can see how permanent all the moments are, and they can look at any moment that interests them. It is just an illusion we have here on Earth that one moment follows another one, like beads on a string, and that once a moment is gone it is gone forever.

When a Tralfamadorian sees a corpse, all he thinks is that the dead person is in bad condition in the particular moment, but that the same person is just fine in plenty of other moments. Now, when I myself hear that somebody is dead, I simply shrug and say what the Tralfamadorians say about dead people, which is "So it goes."- Billy writing a letter to a newspaper describing the Tralfamadorians

- Billy coughed when the door was opened, and when he coughed he shit thin gruel. This was in accordance with the Third Law of Motion according to Sir Isaac Newton. This law tells us that for each reaction there is a reaction which is equal and opposite in direction. This can be useful in rocketry.

- Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt.

- How nice -- to feel nothing, and still get full credit for being alive.

- Derby described the incredible artificial weather that Earthlings sometimes create for other Earthlings when they don't want those other Earthlings to inhabit Earth any more.

- Robert Kennedy, whose summer home is eight miles away from the home I live in all year round, was shot two nights ago. He died last night. So it goes.

Martin Luther King was shot a month ago. He died, too. So it goes.

And everyday my government gives me a count of corpses created by the military service in Vietnam. So it goes.

My father died many years ago now — of natural causes. So it goes. He was a sweet man. He was a gun nut, too. He left me his guns. They rust.

- "Poo-Tee-Weet?"

- Final line

Happy Birthday, Wanda June (1970)

edit- A play, performed in New York City from October 7, 1970 - March 14, 1971

- Things die. All things die.

- Introduction, "About This Play"

- All through the day I'm so confident. That's why I'm such a good salesman, you know? I have confidence, and I look like I have confidence, and that gives other people confidence.

- "Herb Shuttle"

- Maybe God has let everybody who ever lived be reborn — so he or she can see how it ends. Even Pitecanthropus erectus and Australopithecus and Sinanthropus pekensis and the Neanderthalers are back on Earth — to see how it ends. They're all on Times Square — making change for peepshows. Or recruiting Marines.

- "Dr. Norbert Woodley"

- You know what gets me? … How everybody says "fuck" and "shit" all the time. I used to be scared shitless if I'd say "fuck" or "shit" in public, by accident. Now everybody says "fuck" and "shit", "fuck" and "shit" all the time. Something very big must have happened while we were out of the country.

- "Col. Looseleaf Harper"

- The new heroism — put a village idiot into a pressure cooker, seal it up tight, and shoot him at the moon.

- "Harold Ryan"

- Hello, I am Wanda June. Today was going to be my birthday, but I was hit by an ice-cream truck before I could have my party. I am dead now. I am in Heaven. That is why my parents did not pick up my cake at the bakery. I am not mad at the ice-cream truck driver, even though he was drunk when he hit me. It didn't hurt much. It wasn't even as bad as the sting of a bumblebee. I am really happy here! It's so much fun. I'm glad the driver was drunk. If he hadn't been, I might not have gone to Heaven for years and years and years. I would have had to go to high school first, and then beauty college. I would have had to get married and have babies and everything. Now I can just play and play and play. Any time I want any pink cotton candy I can have some. Everybody up here is happy — the animals and the dead soldiers and people who went to the electric chair and everything. They're all glad for whatever sent them here. Nobody is mad. We're all too busy playing shuffleboard. So if you think of killing somebody, don't worry about it. Just go ahead and do it. Whoever you do it to should kiss you for doing it. The soldiers up here just love the shrapnel and the tanks and the bayonets and the dum dums that let them play shuffleboard all the time — and drink beer.

- "Wanda June"

- Don't lecture me on race relations. I don't have a molecule of prejudice. I've been in battle with every kind of man there is. I've been in bed with every kind of woman there is — from a Laplander to a Tierra del Fuegian. If I'd ever been to the South Pole, there'd be a hell of a lot of penguins who looked like me.

- "Harold Ryan"

- No grown woman is a fan of premature ejaculation.

- "Mildred"

- I have this theory about why men kill each other and break things. … Never mind. It's a dumb theory. I was going to say it was all sexual … but everything is sexual … but alcohol.

- "Mildred"

- When I was a naive young recruit in Spain, I used to wonder why soldiers bayoneted oil paintings, shot the noses off statues and defecated into grand pianos. I now understand: it was to teach civilians the deepest sort of respect for men in uniform — uncontrollable fear.

- "Harold Ryan"

- Wars would be a lot better, I think, if guys would say to themselves sometimes "Jesus — I'm not going to do that to the enemy. That's too much."

- "Col. Looseleaf Harper"

Between Time and Timbuktu (1972)

edit- Full title: Between Time and Timbuktu, or Prometheus-5 (the script for a public-television NET Playhouse special based on previously published material)

- This script, it seems to me, is the work of professionals who yearned to be as charming as inspired amateurs can sometimes be.

- "Preface"

- I don't like film. Film is too clankingly real, too permanent, too industrial for me. … The worst thing about film, from my point of view, is that it cripples illusions which I have encouraged people to create in their heads. Film doesn't create illusions. It makes them impossible. It's a bullying form of reality, like the model rooms in the furniture department of Bloomingdale's.

- "Preface"

- I have become an enthusiast for the printed word again. I have to be that, I now understand, because I want to be a character in all of my works. I can do that in print. In a movie, somehow, the author always vanishes. Everything of mine which has been filmed so far has been one character short, and that character is me.

- "Preface"

Breakfast of Champions (1973)

edit- Full title: Breakfast of Champions, Or Goodbye Blue Monday!

- And so on.

- recurring phrase

- Charm was a scheme for making strangers like and trust a person immediately, no matter what the charmer had in mind.

- page 19

- I can have oodles of charm when I want to.

- page 20

- What do I myself think of this particular book? I feel lousy about it, but I always feel lousy about my books.

- This book is my fiftieth-birthday present to myself. I feel as though I am crossing the spine of a roof — having ascended one slope.

I am programmed at fifty to perform childishly — to insult “The Star-Spangled Banner,” to scrawl pictures of a Nazi flag and an asshole and a lot of other things with a felt-tipped pen. To give an idea of the maturity of my illustrations for this book, here is my picture of an asshole:

- I think I am trying to clear my head of all the junk in there — the assholes, the flags, the underpants. Yes — there is a picture in this book of underpants. I’m throwing out characters from my other books, too. I’m not going to put on any more puppet shows.

I think I am trying to make my head as empty as it was when I was born onto this damaged planet fifty years ago.

I suspect that this is something most white Americans, and nonwhite Americans who imitate white Americans, should do. The things other people have put into my head, at any rate, do not fit together nicely, are often useless and ugly, are out of proportion with one another, are out of proportion with life as it really is outside my head.

I have no culture, no humane harmony in my brains. I can’t live without a culture anymore.

So this book is a sidewalk strewn with junk, trash which I throw over my shoulders as I travel in time back to November eleventh, nineteen hundred and twenty-two.

I will come to a time in my backwards trip when November eleventh, accidentally my birthday, was a sacred day called Armistice Day. When I was a boy, and when Dwayne Hoover was a boy, all the people of all the nations which had fought in the First World War were silent during the eleventh minute of the eleventh hour of Armistice Day, which was the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

It was during that minute in nineteen hundred and eighteen, that millions upon millions of human beings stopped butchering one another. I have talked to old men who were on battlefields during that minute. They have told me in one way or another that the sudden silence was the Voice of God. So we still have among us some men who can remember when God spoke clearly to mankind.

Armistice Day has become Veterans' Day. Armistice Day was sacred. Veterans' Day is not.

So I will throw Veterans' Day over my shoulder. Armistice Day I will keep. I don't want to throw away any sacred things.

What else is sacred? Oh, Romeo and Juliet, for instance.

And all music is.

- This is a tale of a meeting of two lonesome, skinny, fairly old white men on a planet which was dying fast.

- Let us devote to unselfishness the frenzy we once gave gold and underpants.

And ready for plucking

You're sixteen

And ready for high school.

- Teachers of children in the United States of America wrote this date on blackboards again and again, and asked the children to memorize it with pride and joy: 1492. The teachers told the children that this was when their continent was discovered by human beings. Actually, millions of human beings were already living full and imaginative lives on the continent in 1492. That was simply the year in which sea pirates began to cheat and rob and kill them.

- Here is how the pirates were able to take whatever they wanted from anybody else: they had the best boats in the world, and they were meaner than anybody else, and they had gunpowder, which was a mixture of potassium nitrate, charcoal, and sulphur. They touched this seemingly listless powder with fire, and it turned violently into gas. This gas blew projectiles out of metal tubes at terrific velocities. The projectiles cut through meat and bone very easily; so the pirates could wreck the wiring or the bellows or the plumbing of a stubborn human being, even when he was far, far away.

The chief weapon of the sea pirates, however, was their capacity to astonish. Nobody else could believe, until it was much too late, how heartless and greedy they were.

- A lot of the people on the wrecked planet were Communists. They had a theory that what was left of the planet should be shared more or less equally among all the people, who hadn’t asked to come to a wrecked planet in the first place. Meanwhile, more babies were arriving all the time—kicking and screaming, yelling for milk.

In some places people would actually try to eat mud or such on gravel while babies were being born just a few feet away.

And so on.

Dwayne Hoover’s and Kilgore Trout’s country, where there was still plenty of everything, was opposed to Communism. It didn’t think that Earthlings who had a lot should share it with others unless they really wanted to, and most of them didn’t want to.

So they didn’t have to.

- Like most science-fiction writers, Trout knew almost nothing about science.

- Roses are red

And ready for plucking

You're sixteen

And ready for high school.

- To be

the eyes

and ears

and conscience

of the Creator of the Universe,

you fool.

- Trout trudged onward, a stranger in a strange land. His pilgrimage was rewarded with new wisdom, which would never have been his had he remained in his basement in Cohoes. He learned the answer to a question many human beings were asking themselves so frantically: "What's blocking the traffic on the westbound barrel of the Midland City stretch of the Interstate?"

- I was on par with the Creator of the Universe there in the dark in the cocktail lounge. I shrunk the Universe to a ball exactly one light-year in diameter. I had it explode. I had it disperse itself again.

Ask me a question, any question. How old is the Universe? It is one half-second old, but the half-second has lasted one quintillion years so far. Who created it? Nobody created it. It has always been here.

What is time? It is a serpent which eats its tail, like this:

This is the snake which uncoiled itself long enough to offer Eve the apple, which looked like this:

What was the apple which Eve and Adam ate? It was the Creator of the Universe.

And so on.

Symbols can be so beautiful, sometimes.

- He was a graduate of West Point, a military academy which turned young men into homicidal maniacs for use in war.

- It was Trout’s fantasy that somebody would be outraged by the footprints. This would give him the opportunity to reply grandly, "What is it that offends you so? I am simply using man’s first printing press. You are reading a bold and universal headline which says ,'I am here, I am here, I am here.'"

- Listen:

The waitress brought me another drink. She wanted to light my hurricane lamp again. I wouldn't let her. "Can you see anything in the dark, with your sunglasses on?" she asked me.

"The big show is inside my head," I said

- We are healthy only to the extent that our ideas are humane.

- Kilgore Trout's epitaph

- Unsourced paraphrase or variant: We are human only to the extent that our ideas remain humane.

- Our awareness is all that is alive and maybe sacred in any of us. Everything else about us is dead machinery.

- I thought Beatrice Keedsler had joined hands with other old-fashioned storytellers to make people believe that life had leading characters, minor characters, significant details, insignificant details, that it had lessons to be learned, tests to be passed, and a beginning, a middle, and an end.

As I approached my fiftieth birthday, I had become more and more enraged and mystified by the idiot decisions made by my countrymen. And then I had come suddenly to pity them, for I understood how innocent and natural it was for them to behave so abominably, and with such abominable results: They were doing their best to live like people invented in story books. This was the reason Americans shot each other so often: It was a convenient literary device for ending short stories and books.

Why were so many Americans treated by their government as though their lives were as disposable as paper facial tissues? Because that was the way authors customarily treated bit-part players in their madeup tales.

And so on.

Once I understood what was making America such a dangerous, unhappy nation of people who had nothing to do with real life, I resolved to shun storytelling. I would write about life. Every person would be exactly as important as any other. All facts would also be given equal weightiness. Nothing would be left out. Let others bring order to chaos. I would bring chaos to order, instead, which I think I have done.

If all writers would do that, then perhaps citizens not in the literary trades will understand that there is no order in the world around us, that we must adapt ourselves to the requirements of chaos instead.

It is hard to adapt to chaos, but it can be done. I am living proof of that: It can be done.

- You are pooped and demoralized. Why wouldn't you be? Of course it is exhausting, having to reason all the time in a universe which wasn't meant to be reasonable.

- Here was what Kilgore Trout cried out to me in my father's voice: "Make me young, make me young, make me young!"

- Last line

- Dear Reader: The title of this book is composed of three words from my novel Cat's Cradle. A wampeter is an object around which the lives of many otherwise unrelated people may revolve. The Holy Grail would be a case in point. Foma are harmless untruths, intended to comfort simple souls. An example: "Prosperity is just around the corner." A granfalloon is a proud and meaningless association of human beings. Taken together, the words form as good an umbrella as any for this collection of some of the reviews and essays I've written, a few of the speeches I made.

- "Preface"

- I have been a soreheaded occupant of a file drawer labeled “Science Fiction” … and I would like out, particularly since so many serious critics regularly mistake the drawer for a urinal.

- "Science Fiction"; originally published in The New York Times Book Review, 5 September 1965

- The two real political parties in America are the Winners and the Losers. The people don’t acknowledge this. They claim membership in two imaginary parties, the Republicans and the Democrats, instead.

- "In a Manner that Must Shame God Himself"

- 'One sacred memory from childhood is perhaps the best education,' said Fyodor Dostoevsky. I believe that, and I hope that many Earthling children will respond to the first human footprint on the moon as a sacred thing. We need sacred things. The footprint could mean, if we let it, that Earthlings have done an unbelievably difficult and beautiful thing which the Creator, for Its own reasons, wanted Earthlings to do.

Footprint.- "Excelsior! We're Going To the Moon! Excelsior!"

- Torture from the air was the only military scheme open to us, I suppose, since the extermination or capture of the North Vietnamese people would have started World War III. In which case, we would have been tortured from the air.

I am sorry we tried torture, I am sorry we tried anything. I hope we will never try torture again. It doesn't work. Human beings are stubborn and brave animals everywhere. They can endure amazing amounts of pain, if they have to. The North Vietnamese and the Vietcong have had to.

Good show.- "Torture and Blubber"

- This theory argues that artists are useful to society because they are so sensitive. They are supersensitive. They keel over like canaries in coal mines filled with poison gas, long before more robust types realize that any danger is there.

- The most useful thing I could do before this meeting is to keel over. On the other hand, artists are keeling over by the thousands every day and nobody seems to pay the least attention.

Playboy interview (1973)

edit- You understand, of course, that everything I say is horseshit.

- I couldn't survive my own pessimism if I didn't have some kind of sunny little dream. … Human beings will be happier — not when they cure cancer or get to Mars or eliminate racial prejudice or flush Lake Erie — but when they find ways to inhabit primitive communities again. That’s my utopia. That's what I want for me.

- It goes against the American storytelling grain to have someone in a situation he can't get out of, but I think this is very usual in life. There are people, particularly dumb people, who are in terrible trouble and never get out of it, because they're not intelligent enough. It strikes me as gruesome and comical that in our culture we have an expectation that man can always solve his problems. This is so untrue that it makes me want to cry — or laugh.

- I've often thought there ought to be a manual to hand to little kids, telling them what kind of planet they're on, why they don't fall off it, how much time they've probably got here, how to avoid poison ivy, and so on. I tried to write one once. It was called Welcome to Earth. But I got stuck on explaining why we don't fall off the planet. Gravity is just a word. It doesn't explain anything. If I could get past gravity, I'd tell them how we reproduce, how long we've been here, apparently, and a little bit about evolution. I didn't learn until I was in college about all the other cultures, and I should have learned that in the first grade. A first grader should understand that his or her culture isn't a rational invention; that there are thousands of other cultures and they all work pretty well; that all cultures function on faith rather than truth; that there are lots of alternatives to our own society. Cultural relativity is defensible and attractive. It's also a source of hope. It means we don't have to continue this way if we don't like it.

Bennington College address (1970)

edit- Address to the graduating class at Bennington College; several of these quotes are cited in the Columbia Dictionary of Quotations as coming from an essay titled "When I Was Twenty-One", but, in fact, there is no essay of that title in Wampeters, Foma & Granfalloons.

- I thought scientists were going to find out exactly how everything worked, and then make it work better. I fully expected that by the time I was twenty-one, some scientist, maybe my brother, would have taken a color photograph of God Almighty — and sold it to Popular Mechanics magazine.

Scientific truth was going to make us so happy and comfortable. What actually happened when I was twenty-one was that we dropped scientific truth on Hiroshima.

- We would be a lot safer if the Government would take its money out of science and put it into astrology and the reading of palms. I used to think that science would save us, and science certainly tried. But we can't stand any more tremendous explosions, either for or against democracy.

- I know that millions of dollars have been spent to produce this splendid graduating class, and that the main hope of your teachers was, once they got through with you, that you would no longer be superstitious. I'm sorry — I have to undo that now. I beg you to believe in the most ridiculous superstition of all: that humanity is at the center of the universe, the fulfiller or the frustrator of the grandest dreams of God Almighty.

If you can believe that, and make others believe it, then there might be hope for us. Human beings might stop treating each other like garbage, might begin to treasure and protect each other instead. Then it might be all right to have babies again.

- About astrology and palmistry: They are good because they make people feel vivid and full of possibilities. They are communism at its best. Everybody has a birthday and almost everybody has a palm.

- Which brings us to the arts, whose purpose, in common with astrology, is to use frauds in order to make human beings seem more wonderful than they really are. Dancers show us human beings who move much more gracefully than human beings really move. Films and books and plays show us people talking much more entertainingly than people really talk, make paltry human enterprises seem important. Singers and musicians show us human beings making sounds far more lovely than human beings really make. Architects give us temples in which something marvelous is obviously going on. Actually, practically nothing is going on inside. And on and on.

- The arts put man at the center of the universe, whether he belongs there or not. Military science, on the other hand, treats man as garbage — and his children, and his cities, too. Military science is probably right about the contemptibility of man in the vastness of the universe. Still — I deny that contemptibility, and I beg you to deny it, through the creation of appreciation of art.

- A great swindle of our time is the assumption that science has made religion obsolete. All science has damaged is the story of Adam and Eve and the story of Jonah and the Whale. Everything else holds up pretty well, particularly lessons about fairness and gentleness. People who find those lessons irrelevant in the twentieth century are simply using science as an excuse for greed and harshness. Science has nothing to do with it, friends.

- Full title: Slapstick, or Lonesome No More

- Hi Ho

- Prologue, and a recurring phrase throughout the book.

- Love is where you find it. I think it is foolish to go looking for it, and I think it can often be poisonous.

- Prologue

- I wish that people who are conventionally supposed to love each other would say to each other, when they fight, "Please — a little less love, and a little more common decency."

- Prologue

- Eliza and I composed a precocious critique of the Constitution of the United States of America … We argued that is was as good a scheme for misery as any, since its success in keeping the common people reasonably happy and proud depended on the strength of the people themselves — and yet it prescribed no practical machinery which would tend to make the people, as opposed to their elected representatives, strong.

We said it was possible that the framers of the Constitution were blind to the beauty of persons who were without great wealth or powerful friends or public office, but who were nonetheless genuinely strong.

We thought it was more likely, though, that their framers had not noticed that it was natural, and therefore almost inevitable, that human beings in extraordinary and enduring situations should think of themselves of composing new families. Eliza and I pointed out that this happened no less in democracies than in tyrannies, since human beings were the same the wide world over, and civilized only yesterday.

Elected representatives, hence, could be expected to become members of the famous and powerful family of elected representatives — which would, perfectly naturally, make them wary and squeamish and stingy with respect to all the other sorts of families which, again, perfectly naturally, subdivided mankind.

Eliza and I … proposed that the Constitution be amended so as to guarantee that every citizen, no matter how humble, or crazy or incompetent or deformed, somehow be given membership in some family as covertly xenophobic and crafty as the one their public servants formed.- Ch. 6

- Why don't you take a flying fuck at a rolling doughnut. Why don't you take a flying fuck at the mooooooooooooon!

- Ch. 33, and passim

- History is merely a list of surprises. … It can only prepare us to be surprised yet again. Please write that down.

- Ch. 48

- If you can do no good, at least do no harm.

- Sally In The Garden:

Sally in the garden,

Siftin' cinders,

Lifted up her leg,

And farted like a man,

The bursting of her bloomers broke sixteen winders,

The cheeks of her ass went (blam, blam, blam)

- Labor history was pornography of a sort in those days, and even more so in these days. In public schools and in the homes of nice people it was and remains pretty much taboo to tell tales of labor's sufferings and derring-do.

- p. 12 (prologue)

- What is flirtatiousness but an argument that life must go on and on and on?

- p. 24

- Congressman Nixon had asked me why, as the son of immigrants who had been treated so well by Americans, as a man who had been treated like a son and been sent to Harvard by an American capitalist, I had been so ungrateful to the American economic system.

The answer I gave him was not original. Nothing about me has ever been original. I repeated what my one-time hero, Kenneth Whistler, had said in reply to the same general sort of question long, long ago. Whistler had been a witness at a trial of strikers accused of violence. The judge had become curious about him, had asked him why such a well-educated man from such a good family would so immerse himself in the working class.

My stolen answer to Nixon was this: "Why? The Sermon on the Mount, sir."

- You couldn't help that you were born without a heart. At least you tried to believe what the people with hearts believed — so you were a good man just the same.

- "That was the strength of the Nazis," she said. "They understood God better than anyone. They knew how to make him stay away."

Palm Sunday (1981)

edit- An Autobiographical Collage

- What we will be seeking … for the rest of our lives will be large, stable communities of like-minded people, which is to say relatives. They no longer exist. The lack of them is not only the main cause, but probably the only cause of our shapeless discontent in the midst of such prosperity.

- "Thoughts of a Free Thinker", commencement address, Hobart and William Smith Colleges (26 May 1974)

- What should young people do with their lives today? Many things, obviously. But the most daring thing is to create stable communities in which the terrible disease of loneliness can be cured.

- "Thoughts of a Free Thinker", commencement address, Hobart and William Smith Colleges (26 May 1974)

- I think it can be tremendously refreshing if a creator of literature has something on his mind other than the history of literature so far. Literature should not disappear up its own asshole, so to speak.

- "Self-Interview", originally appeared in The Paris Review no. 69 (1977)

- [Gay Talese's Thy Neighbor's Wife] is for me a secretly deep history of a generation of middle-class American males, my own, which was taught by parents and athletic coaches and scoutmasters and military chaplains and quack doctors and so on to be deeply ashamed of masturbation and wet dreams.

And the hidden plea in the book is one which first appeared in my eyes when I was fourteen, say, and which has not vanished entirely to this day. It is part of the mystery of me. The plea is addressed by old-fashioned males forever full of jism to any pretty human female, on the street, in a magazine, in a movie — anywhere. The plea is this: "Please, pretty lady, don't make me play with my private parts again."- "The Sexual Revolution" (ndg)

- Jokes can be noble. Laughs are exactly as honorable as tears. Laughter and tears are both responses to frustration and exhaustion, to the futility of thinking and striving anymore. I myself prefer to laugh, since there is less cleaning up to do afterward — and since I can start thinking and striving again that much sooner.

- "Palm Sunday", a sermon delivered at St. Clement's Church, New York City (ndg), originally published in The Nation as "Hypocrites You Always Have With You" (ndg)

- As for literary criticism in general: I have long felt that any reviewer who expresses rage and loathing for a novel or a play or a poem is preposterous. He or she is like a person who has put on full armor and attacked a hot fudge sundae or a banana split.

- The People One Knows

- And I believe that reading and writing are the most nourishing forms of meditation anyone has so far found. By reading the writings of the most interesting minds in history, we meditate with our own minds and theirs as well. This to me is a miracle.

- "The Noodle Factory", speech given at the dedication of the Shain Library at Connecticut College, New London

Deadeye Dick (1982)

edit- To the as-yet-unborn, to all innocent wisps of undifferentiated nothingness: Watch out for life.

I have caught life. I have come down with life. I was a wisp of undifferentiated nothingness, and then a little peephole opened quite suddenly. Light and sound poured in. Voices began to describe me and my surroundings. Nothing they said could be appealed.

- This is my principal objection to life, I think: It is too easy, when alive, to make perfectly horrible mistakes.

- p. 6

- Many people found our house spooky, and the attic in fact as full of evil when I was born. It housed a collection of more than three hundred antique and modern firearms. Father had bought them during his and Mother's six-month honeymoon in Europe in 1922. Father thought them beautiful, but they might as well have been copperheads and rattlesnakes. They were murder.

- I hadn't aimed at anything. If I had thought of the bullet's hitting anything, I don't remember now. I was the great marksman, anyway. If I aimed at nothing, then nothing is what I would hit. The bullet was a symbol, and nobody was ever hurt by a symbol. It was a farewell to my childhood and a confirmation of my manhood. Why didn't I use a blank cartridge? What kind of a symbol would that have been?

- Describing an accident in which the narrator, as a child, accidentally shot a woman

- My wife has been killed by a machine which should never have come into the hands of any human being. It is called a firearm. It makes the blackest of all human wishes come true at once, at a distance: that something die. There is evil for you. We cannot get rid of mankind's fleetingly evil wishes. We can get rid of the machines that make them come true. I give you a holy word: DISARM.

- Statement of the husband of the woman killed in the accident

- You want to know something? We are still in the Dark Ages. The Dark Ages — they haven't ended yet.

- Closing lines

- Mere opinions, in fact, were as likely to govern people's actions as hard evidence, and were subject to sudden reversals as hard evidence could never be. So the Galapagos Islands could be hell in one moment and heaven in the next, and Julius Caesar could be a statesman in one moment and a butcher in the next, and Ecuadorian paper money could be traded for food, shelter, and clothing in one moment and line the bottom of a birdcage in the next, and the universe could be created by God Almighty in one moment and by a big explosion in the next — and on and on.

- That, in my opinion, was the most diabolical aspect of those old-time brains: They would tell their owners, in effect, "Here's a crazy thing we could actually do, probably, but would never do it, of course. It's just fun to think about."

And then, as though in trances, the people would really do it — have slaves fight each other to death in the Colosseum, or burn people alive in the public square for holding opinions which were locally unpopular, or build factories whose only purpose was to kill people in industrial quantities, or to blow up whole cities, and on and on.

- Why so many of us a million years ago purposely knocked out major chunks of our brains with alcohol from time to time remains an interesting mystery. It may be we were trying to give evolution a shove in the right direction — in the direction of smaller brains.

- Fish! Fish! Fish!

- Time is liquid. One moment is no more important than any other and all moments quickly run away.

- p. 82

- I've got news for Mr. Santayana: we're doomed to repeat the past no matter what. That's what it is to be alive.

- p. 91, referring to George Santayana: "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it"

- Who is more to be pitied, a writer bound and gagged by policemen or one living in perfect freedom who has nothing more to say?

- p. 168

- What is literature but an insider's newsletter about affairs relating to molecules, of no importance to anything in the Universe but a few molecules who have the disease called "thought".

- p. 188

- "We're having a celebration, so all sorts of things have been said which are not true," I said. "That's how to act at a party."

- "I can't help it," I said. "My soul knows my meat is doing bad things, and is embarrassed. But my meat just keeps right on doing bad, dumb things."

"You and your what?" he said.

"My soul and my meat," I said.

"They're separate?" he said.