The Story of Civilization

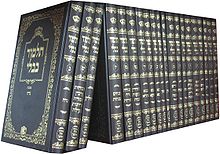

11-volume set of books covering Western history

(Redirected from Our oriental heritage)

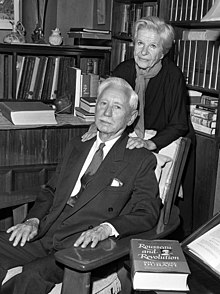

The Story of Civilization, by husband and wife Will and Ariel Durant, is an 11-volume set of books covering Western history for the general reader.

Quotes

editI - Our Oriental Heritage (1935)

edit- I wish to tell as much as I can, in as little space as I can, of the contributions that genius and labor have made to the cultural heritage of mankind — to chronicle and contemplate, in their causes, character and effects, the advances of invention, the varieties of economic organization, the experiments in government, the aspirations of religion, the mutations of morals and manners, the masterpieces of literature, the development of science, the wisdom of philosophy, and the achievements of art. I do not need to be told how absurd this enterprise is, nor how immodest is its very conception … Nevertheless I have dreamed that despite the many errors inevitable in this undertaking, it may be of some use to those upon whom the passion for philosophy has laid the compulsion to try to see things whole, to pursue perspective, unity and understanding through history in time, as well as to seek them through science in space. … Like philosophy, such a venture [as the creation of these 11 volumes] has no rational excuse, and is at best but a brave stupidity; but let us hope that, like philosophy, it will always lure some rash spirits into its fatal depths.

- Preface

The Establishment of Civilization

edit- Man is not willingly a political animal. The human male associates with his fellows less by desire than by habit, imitation, and the compulsion of circumstance; he does not love society so much as he fears solitude. He combines with other men because isolation endangers him, and because there are many things that can be done better together than alone; in his heart he is a solitary individual, pitted heroically against the world.

- Will Durant, The Story of Civilization: Part 1 – Our Oriental Heritage (1935), Chapter 3, Section 1

- If the average man had had his way there would probably never have been any state. Even today he resents it, classes death with taxes, and yearns for that government which governs least. If he asks for many laws it is only because he is sure that his neighbor needs them; privately he is an unphilosophical anarchist, and thinks laws in his own case superfluous. In the simplest societies there is hardly any government. Primitive hunters tend to accept regulation only when they join the hunting pack and prepare for action. The Bushmen usually live in solitary families; the Pygmies of Africa and the simplest natives of Australia admit only temporarily of political organization, and then scatter away to their family groups; the Tasmanians had no chiefs, no laws, no regular government; the Veddahs of Ceylon formed small circles according to family relationship, but had no government; the Kubus of Sumatra "live without men in authority" every family governing itself; the Fuegians are seldom more than twelve together; the Tungus associate sparingly in groups of ten tents or so; the Australian "horde" is seldom larger than sixty souls. In such cases association and cooperation are for special purposes, like hunting; they do not rise to any permanent political order.

- Ch. III : The Political Elements of Civilization, p. 21

The Near East

edit- "For barbarism is always around civilization, amid it and beneath it, ready to engulf it by arms, or mass migration, or unchecked fertility. Barbarism is like the jungle; it never admits its defeat; it waits patiently for centuries to recover the territory it has lost." (page 265)

- The civilization of Babylonia was not as fruitful for humanity as Egypt’s, not as varied and profound as India’s, not as subtle and mature as China’s. And yet it was from Babylonia that those fascinating legends came which, through the literary artistry of the Jews, became an inseparable portion of Europe’s religious lore; it was from Babylonia, rather than from Egypt, that the roving Greeks brought to their city-states and thence to Rome and ourselves, the foundations of mathematics, astronomy, medicine, grammar, lexicography, archeology, history, and philosophy. The Greek names for the metals and the constellations, for weights and measures, for musical instruments and many drugs, are translations, sometimes mere transliterations, of Babylonian names.

India and Her Neighbors

editXIV : The Foundations of India

edit- In the days when historians supposed that history had begun with Greece, Europe gladly believed that India had been a hotbed of barbarism until the “Aryan” cousins of the European peoples had migrated from the shores of the Caspian to bring the arts and sciences to a savage and benighted peninsula. Recent researches have marred this comforting picture—as future researches will change the perspective of these pages. In India, as elsewhere, the beginnings of civilization are buried in the earth, and not all the spades of archaeology will ever quite exhume them.

- Nothing should more deeply shame the modern student than the recency and inadequacy of his acquaintance with India. Here is a vast peninsula of nearly two million square miles; two-thirds as large as the United States, and twenty times the size of its master, Great Britain; 320,000,000 souls, more than in all North and South America combined, or one-fifth of the population of the earth; an impressive continuity of development and civilization from Mohenjo-daro, 2900 B.C. or earlier, to Gandhi, Raman and Tagore; faiths compassing every stage from barbarous idolatry to the most subtle and spiritual pantheism; philosophers playing a thousand variations on one monistic theme from the Upanishads eight centuries before Christ to Shankara eight centuries after him; scientists developing astronomy three thousand years ago, and winning Nobel prizes in our own time; a democratic constitution of untraceable antiquity in the villages, and wise and beneficent rulers like Ashoka and Akbar in the capitals; minstrels singing great epics almost as old as Homer, and poets holding world audiences today; artists raising gigantic temples for Hindu gods from Tibet to Ceylon and from Cambodia to Java, or carving perfect palaces by the score for Mogul kings and queens — this is the India that patient scholarship is now opening up, like a new intellectual continent, to that Western mind which only yesterday thought civilization an exclusively European thing.

- Ch. XIV : The Foundations of India § I : Scene of the Drama

XVI : From Alexander to Aurangzeb

edit- The Mohammedan Conquest of India is probably the bloodiest story in history. It is a discouraging tale, for its evident moral is that civilization is a precarious thing, whose delicate complex of order and liberty, culture and peace may at any time be overthrown by barbarians invading from without or multiplying within.

- Ch. XVI : From Alexander to Aurangzeb, § VI : The Moslem Conquest; this has become misquoted in paraphrased form as : "The Islamic conquest of India is probably the bloodiest story in history. It is a discouraging tale, for its evident moral is that civilization is a precious good, whose delicate complex of order and freedom, culture and peace, can at any moment be overthrown by barbarians invading from without or multiplying within.

- It is in the nature of governments to degenerate; for power, as Shelley said, poisons every hand that touches it. The excesses of the Delhi Sultans lost them the support not only of the Hindu population, but of their Moslem followers. When fresh invasions came from the north these Sultans were defeated with the same ease with which they themselves had won India.

- Ch. XVI : From Alexander to Aurangzeb, § VII : Akbar the Great

- While Catholics were murdering Protestants in France, and Protestants, under Elizabeth, were murdering Catholics in England, and the Inquisition was killing and robbing Jews in Spain, and Bruno was being burned at the stake in Italy, Akbar invited the representatives of all the religions in his empire to a conference, pledged them to peace, issued edicts of toleration for every cult and creed, and, as evidence of his own neutrality, married wives from the Brahman, Buddhist, and Mohammedan faiths.

His greatest pleasure, after the fires of youth had cooled, was in the free discussion of religious beliefs. … The King took no stock in revelations, and would accept nothing that could not justify itself with science and philosophy. It was not unusual for him to gather friends and prelates of various sects together, and discuss religion with them from Thursday evening to Friday noon. When the Moslem mullahs and the Christian priests quarreled he reproved them both, saying that God should be worshiped through the intellect, and not by a blind adherence to supposed revelations. "Each person," he said, in the spirit — and perhaps through the influence — of the Upanishads and Kabir, "according to his condition gives the Supreme Being a name; but in reality to name the Unknowable is vain."- Ch. XVI : From Alexander to Aurangzeb, § VII : Akbar the Great

XVII : The Life of the People

edit- The people enjoyed a considerable measure of liberty under the native dynasties, partly through the autonomous communities in the villages and the trade guilds in the towns, and partly through the limitations that the Brahman aristocracy placed upon the authority of the king. ... The Mohammedan rulers paid less attention than their Hindu predecessors to these ideals and checks; they were a conquering minority, and rested their rule frankly on the superiority of their guns. “The army,” says a Moslem historian, with charming clarity, “is the source and means of government.” Akbar was an exception, for he relied chiefly upon the good will of a people prospering under his mild and benevolent despotism. Perhaps in the circumstances his was the best government possible. Its vital defect, as we have seen, lay in its dependence upon the character of the king; the supreme centralized authority that proved beneficent under Akbar proved ruinous under Aurangzeb. Having been raised up by violence, the Afghan and Mogul rulers were always subject to recall by assassination; and wars of succession were almost as expensive—though not as disturbing to economic life—as a modern election.

- Even their enemies admit their courtesy, and a generous Britisher sums up his long experience by ascribing to the higher classes in Calcutta “polished manners, clearness and comprehensiveness of understanding, liberality of feeling, and independence of principle, that would have stamped them gentlemen in any country in the world.”

- Cleanliness was literally next to godliness in India; hygiene was not, as Anatole France thought it, la seule morale, but it was made an essential part of piety. Manu laid down, many centuries ago, an exacting code of physical refinement. “Early in the morning,” one instruction reads, “let him” (the Brahman) “bathe, decorate his body, clean his teeth, apply collyrium to his eyes, and worship the gods.” The native schools made good manners and personal cleanliness the first courses in the curriculum. Every day the caste Hindu would bathe his body, and wash the simple robe he was to wear; it seemed to him abominable to use the same garment, unwashed, for more than a day. “The Hindus,” said Sir William Huber, “stand out as examples of bodily cleanliness among Asiatic races, and, we may add, among the races of the world. The ablutions of the Hindu have passed into a proverb.”

- The Brahman usually washed his hands, feet and teeth before and after each meal; he ate with his fingers from food on a leaf, and thought it unclean to use twice a plate, a knife or a fork; and when finished he rinsed his mouth seven times. The toothbrush was always new—a twig freshly plucked from a tree; to the Hindu it seemed disreputable to brush the teeth with the hair of an animal, or to use the same brush twice: so many are the ways in which men may scorn one another.

- The women wore a flowing robe—colorful silk sari, or homespun khaddar—which passed over both shoulders, clasped the waist tightly, and then fell to the feet; often a few inches of bronze flesh were left bare below the breast. Hair was oiled to guard it against the desiccating sun; men divided theirs in the center and drew it together into a tuft behind the left ear; women coiled a part of theirs upon their heads, but let the rest hang free, often decorating it with flowers, or covering it with a scarf. The men were handsome, the young women were beautiful and all presented a magnificent carriage; an ordinary Hindu in a loin cloth often had more dignity than a European diplomat completely equipped. Pierre Loti thought it “incontestable that the beauty of the Aryan race reaches its highest development of perfection and refinement among the upper class” in India. Both sexes were adept in cosmetics, and the women felt naked without jewelry. A ring in the left nostril denoted marriage. On the forehead, in most cases, was a painted symbol of religious faith.

- This system had grown more rigid and complex since the Vedic period; not only because it is in the nature of institutions to become stiff with age, but because the instability of the political order, and the overrunning of India by alien peoples and creeds, had intensified caste as a barrier to the mixture of Moslem and Hindu blood. ...It (the caste system) offered an escape from the plutocracy or the military dictatorship which are apparently the only alternatives to aristocracy; it gave to a country shorn of political stability by a hundred invasions and revolutions a social, moral and cultural order and continuity rivaled only by the Chinese. Amid a hundred anarchic changes in the state, the Brahmans maintained, through the system of caste, a stable society, and preserved, augmented and transmitted civilization. The nation bore with them patiently, even proudly, because every one knew that in the end they were the one indispensable government of India.

- Nevertheless, despite all this equipment, woman fared poorly in India. Her high status in Vedic days was lost under priestly influence and Mohammedan example. The Code of Manu set the tone against her in phrases reminiscent of an early stage in Christian theology... Doubtless the influx of Islamic ideas had something to do with the decline in the status of woman in India after Vedic days. The custom of purdah (curtain)—the seclusion of married women—came into India with the Persians and the Mohammedans, and has therefore been stronger in the north than in the south. Partly to protect their wives from the Moslems, Hindu husbands developed a system of purdah so rigid that a respectable woman could show herself only to her husband and her sons, and could move in public only under a heavy veil; even the doctor who treated her and took her pulse had to do so through a curtain.

- It will seem incredible to the provincial mind that the same people that tolerated such institutions as child marriage, temple prostitution and suttee was also pre-eminent in gentleness, decency and courtesy. Aside from a few devadasis, prostitutes were rare in India, and sexual propriety was exceptionally high. “It must be admitted,” says the unsympathetic Dubois, “that the laws of etiquette and social politeness are much more clearly laid down, and much better observed by all classes of Hindus, even by the lowest, than they are by people of corresponding social position in Europe.” ... A Hindu woman might go anywhere in public without fear of molestation or insult; indeed the risk, as the Oriental saw the matter, was all on the other side. Manu warns men: “Woman is by nature ever inclined to tempt man; hence a man should not sit in a secluded place even with his nearest female relative”; and he must never look higher than the ankles of a passing girl.

- The Hindus chose child marriage as the lesser evil, and tried to mitigate its dangers by establishing, between the marriage and its consummation, a period in which the bride should remain with her parents until the coming of puberty. The institution was old, and therefore holy; it had been rooted in the desire to prevent intercaste marriage through casual sexual attraction; it was later encouraged by the fact that the conquering and otherwise ruthless Moslems were restrained by their religion from carrying away married women as slaves; and finally it took rigid form in the parental resolve to protect the girl from the erotic sensibilities of the male.

XVIII : The Paradise of the Gods

edit- As in Mediterranean Christianity, these saints became so popular that they almost crowded out the head of the pantheon in worship and art. The veneration of relics, the use of holy water, candles, incense, the rosary, clerical vestments, a liturgical dead language, monks and nuns, monastic tonsure and celibacy, confession, fast days, the canonization of saints, purgatory and masses for the dead flourished in Buddhism as in medieval Christianity, and seem to have appeared in Buddhism first.II Mahayana became to Hinayana or primitive Buddhism what Catholicism was to Stoicism and primitive Christianity. Buddha, like Luther, had made the mistake of supposing that the drama of religious ritual could be replaced with sermons and morality; and the victory of a Buddhism rich in myths, miracles, ceremonies and intermediating saints corresponds to the ancient and current triumph of a colorful and dramatic Catholicism over the austere simplicity of early Christianity and modern Protestantism.

- That same popular preference for polytheism, miracles and myths which destroyed Buddha’s Buddhism finally destroyed, in India, the Buddhism of the Greater Vehicle itself. For—to speak with the hindsight wisdom of the historian—if Buddhism was to take over so much of Hinduism, so many of its legends, its rites and its gods, soon very little would remain to distinguish the two religions; and the one with the deeper roots, the more popular appeal, and the richer economic resources and political support would gradually absorb the other....

The final blow came from without, and was in a sense invited by Buddhism itself. The prestige of the Sangha, or Buddhist Order, had, after Ashoka, drawn the best blood of Magadha into a celibate and pacific clergy; even in Buddha’s time some patriots had complained that “the monk Gautama causes fathers to beget no sons, and families to become extinct.” The growth of Buddhism and monasticism in the first year of our era sapped the manhood of India, and conspired with political division to leave India open to easy conquest. When the Arabs came, pledged to spread a simple and stoic monotheism, they looked with scorn upon the lazy, venal, miracle-mongering Buddhist monks; they smashed the monasteries, killed thousands of monks, and made monasticism unpopular with the cautious. The survivors were re-absorbed into the Hinduism that had begotten them; the ancient orthodoxy received the penitent heresy, and “Brahmanism killed Buddhism by a fraternal embrace.” Brahmanism had always been tolerant; in all the history of the rise and fall of Buddhism and a hundred other sects we find much disputation, but no instance of persecution. On the contrary Brahmanism eased the return of the prodigal by proclaiming Buddha a god (as an avatar of Vishnu), ending animal sacrifice, and accepting into orthodox practice the Buddhist doctrine of the sanctity of all animal life. Quietly and peacefully, after half a thousand years of gradual decay, Buddhism disappeared from India. - Meanwhile it was winning nearly all the remainder of the Asiatic world. Its ideas, its literature and its art spread to Ceylon and the Malay Peninsula in the south, to Tibet and Turkestan in the north, to Burma, Siam, Cambodia, China, Korea and Japan in the east; in this way all of these regions except the Far East received as much civilization as they could digest, precisely as western Europe and Russia received civilization from Roman and Byzantine monks in the Middle Ages. The cultural zenith of most of these nations came from the stimulus of Buddhism.

- In Cambodia, or Indo-China, Buddhism conspired with Hinduism to provide the religious framework for one of the richest ages in the history of Oriental art.

- Buddhism, like Christianity, won its greatest triumphs outside the land of its birth; and it won them without shedding a drop of blood.

- The Buddhism of Burma is probably the purest now extant, and its monks often approach the ideal of Buddha; under their ministrations the 13,000,000 inhabitants of Burma have reached a standard of living considerably higher than that of India.

- In the seventh century of our era the enlightened warrior, Srong-tsan Gampo, established an able government in Tibet, annexed Nepal, built Lhasa as his capital, and made it rich as a halfway house in Chinese-Indian trade. Having invited Buddhist monks to come from India and spread Buddhism and education among his people, he retired from rule for four years in order to learn how to read and write, and inaugurated the Golden Age of Tibet. Thousands of monasteries were built in the mountains and on the great plateau; and a voluminous Tibetan canon of Buddhist books was published, in three hundred and thirty-three volumes, which preserved for modern scholarship many works whose Hindu originals have long been lost. Here, eremitically sealed from the rest of the world, Buddhism developed into a maze of superstitions, monasticism and ecclesiasticism rivaled only by early medieval Europe; and the Dalai Lama (or “All-Embracing Priest”), hidden away in the great Potala monastery that overlooks the city of Lhasa, is still believed by the good people of Tibet to be the living incarnation of the Bodhisattwa Avalokiteshvafa.

- The worship of Shiva is one of the oldest, most profound and most terrible elements in Hinduism. Sir John Marshall reports “unmistakable evidence” of the cult of Shiva at Mohenjo-daro, partly in the form of a three-headed Shiva, partly in the form of little stone columns which he presumes to be as phallic as their modern counterparts. “Shivaism,” he concludes, “is therefore the most ancient living faith in the world.”... Never has another people dared to face the impermanence of forms, and the impartiality of nature, so frankly, or to recognize so clearly that evil balances good, that destruction goes step by step with creation, and that all birth is a capital crime, punishable with death.

- This is the Law of Karma—the Law of the Deed—the law of causality in the spiritual world; and it is the highest and most terrible law of all... Good Hindus do not kill insects if they can possibly avoid it; “even those whose aspirations to virtue are modest treat animals as humble brethren rather than as lower creatures over whom they have dominion by divine command.”

- When heresies or strange gods became dangerously popular they tolerated them, and then absorbed them into the capacious caverns of Hindu belief; one god more or less could not make much difference in India. Hence there has been comparatively little sectarian animosity within the Hindu community, though much between Hindus and Moslems; and no blood has been shed for religion in India except by its invaders. Intolerance came with Islam and Christianity; the Moslems proposed to buy Paradise with the blood of “infidels,” and the Portuguese, when they captured Goa, introduced the Inquisition into India.

- “The Buddhists,” says Fergusson, “kept five centuries in advance of the Roman Church in the invention and use of all the ceremonies and forms common to both religions.” Edmunds has shown in detail the astonishing parallelism between the Buddhist and the Christian gospels. However, our knowledge of the beginnings of these customs and beliefs is too vague to warrant positive conclusions as to priority.

XIX : The Life of the Mind

edit- INDIA’S work in science is both very old and very young: young as an independent and secular pursuit, old as a subsidiary interest of her priests.

- The greatest of Hindu astronomers and mathematicians, Aryabhata, discussed in verse such poetic subjects as quadratic equations, sines, and the value of π; he explained eclipses, solstices and equinoxes, announced the sphericity of the earth and its diurnal revolution on its axis, and wrote, in daring anticipation of Renaissance science: “The sphere of the stars is stationary, and the earth, by its revolution, produces the daily rising and setting of planets and stars.” His most famous successor, Brahmagupta, systematized the astronomic knowledge of India, but obstructed its development by rejecting Aryabhata’s theory of the revolution of the earth. These men and their followers adapted to Hindu usage the Babylonian division of the skies into zodiacal constellations; they made a calendar of twelve months, each of thirty days, each of thirty hours, inserting an intercalary month every five years; they calculated with remarkable accuracy the diameter of the moon, the eclipses of the moon and the sun, the position of the poles, and the position and motion of the major stars. They expounded the theory, though not the law, of gravity when they wrote in the Siddhantas: “The earth, owing to its force of gravity, draws all things to itself.”

- To make these complex calculations the Hindus developed a system of mathematics superior, in everything except geometry, to that of the Greeks. Among the most vital parts of our Oriental heritage are the “Arabic” numerals and the decimal system, both of which came to us, through the Arabs, from India. The miscalled “Arabic” numerals are found on the Rock Edicts of Ashoka (256 B.C.), a thousand years before their occurrence in Arabic literature.

- The decimal system was known to Aryabhata and Brahmagupta long before its appearance in the writings of the Arabs and the Syrians; it was adopted by China from Buddhist missionaries; and Muhammad Ibn Musa al-Khwarazmi, the greatest mathematician of his age (d. ca. 850 A.D.), seems to have introduced it into Baghdad. The oldest known use of the zero in Asia or EuropeI is in an Arabic document dated 873 A.D., three years sooner than its first known appearance in India; but by general consent the Arabs borrowed this too from India, and the most modest and most valuable of all numerals is one of the subtle gifts of India to mankind.

- Algebra was developed in apparent independence by both the Hindus and the Greeks; but our adoption of its Arabic name (al-jabr, adjustment) indicates that it came to western Europe from the Arabs—i.e., from India—rather than from Greece. The great Hindu leaders in this field, as in astronomy, were Aryabhata, Brahmagupta and Bhaskara. The last (b. 1114 A.D.), appears to have invented the radical sign, and many algebraic symbols. These men created the conception of a negative quantity, without which algebra would have been impossible; they formulated rules for finding permutations and combinations; they found the square root of 2, and solved, in the eighth century A.D., indeterminate equations of the second degree that were unknown to Europe until the days of Euler a thousand years later.14 They expressed their science in poetic form, and gave to mathematical problems a grace characteristic of India’s Golden Age.

- The priority of India is clearer in philosophy than in medicine, though here too origins are veiled, and every conclusion is an hypothesis. Some Upanishads are older than any extant form of Greek philosophy, and Pythagoras, Parmenides and Plato seem to have been influenced by Indian metaphysics; but the speculations of Thales, Anaximander, Anaximenes, Heraclitus, Anaxagoras and Empedocles not only antedate the secular philosophy of the Hindus, but bear a sceptical and physical stamp suggesting any other origin than India. Victor Cousin believed that “we are constrained to see in this cradle of the human race the native land of the highest philosophy.” It is more probable that no one of the civilizations known to us was the originator of any of the elements of civilization.

- But nowhere else has the lust for philosophy been so strong as in India. It is, with the Hindus, not an ornament or a recreation, but a major interest and practice of life itself; and sages receive in India the honor bestowed in the West upon men of wealth or action. What other nation has ever thought of celebrating festivals with gladiatorial debates between the leaders of rival philosophical schools?

- In a Rajput painting of the eighteenth century we see a typical Indian “School of Philosophy”—the teacher sits on a mat under a tree, and his pupils squat on the grass before him. Such scenes were to be witnessed everywhere, for teachers of philosophy were as numerous in India as merchants in Babylonia. No other country has ever had so many schools of thought. In one of Buddha’s dialogues we learn that there were sixty-two distinct theories of the soul among the philosophers of his time. “This philosophical nation par excellence” says Count Keyserling, “has more Sanskrit words for philosophical and religious thought than are found in Greek, Latin and German combined.”

- In effect, therefore, the philosophers of India enjoyed far more liberty than their Scholastic analogues in Europe, though less, perhaps, than the thinkers of Christendom under the enlightened Popes of the Renaissance.

- In his short life of thirty-two years Shankara achieved that union of sage and saint, of wisdom and kindliness, which characterizes the loftiest type of man produced in India... There is much metaphysical wind in these discourses, and arid deserts of textual exposition; but they may be forgiven in a man who at the age of thirty could be at once the Aquinas and the Kant of India... Shankara establishes the source of his philosophy at a remote and subtle point never quite clearly visioned again until, a thousand years later, Immanuel Kant wrote his Critique of Pure Reason.

- The first algebraist known to us, the Greek Diophantus (360 A.D.), antedates Aryabhata by a century; but Cajori believes that he took his lead from India.

- The Mohammedan invasions put an end to the great age of Hindu philosophy. The assaults of the Moslems, and later of the Christians, upon the native faith drove it, for self-defense, into a timid unity that made treason of all debate, and stifled creative heresy in a stagnant uniformity of thought. By the twelfth century the system of the Vedanta, which in Shankara had tried to be a religion for philosophers, was reinterpreted by such saints as Ramanuja (ca. 1050) into an orthodox worship of Vishnu, Rama and Krishna. Forbidden to think new thoughts, philosophy became not only scholastic but barren; it accepted its dogmas from the priesthood, and proved them laboriously by distinctions without difference, and logic without reason.

XX : The Literature of India

edit- At a very early date India began to trace the roots, history, relations and combinations of words. By the fourth century B.C. she had created for herself the science of grammar, and produced probably the greatest of all known grammarians, Panini. The studies of Panini, Patanjali (ca. 150 A.D.) and Bhartrihari (ca. 650) laid the foundations of philology; and that fascinating science of verbal genetics owed almost its life in modern times to the rediscovery of Sanskrit.

- Every Hindu village had its schoolmaster, supported out of the public funds; in Bengal alone, before the coming of the British, there were some eighty thousand native schools—one to every four hundred population. The percentage of literacy under Ashoka was apparently higher than in India today.

- From his Guru the student might pass, about the age of sixteen, to one of the great universities that were the glory of ancient and medieval India: Benares, Taxila, Vidarbha, Ajanta, Ujjain, or Nalanda. Benares was the stronghold of orthodox Brahman learning in Buddha’s days as in ours; Taxila, at the time of Alexander’s invasion, was known to all Asia as the leading seat of Hindu scholarship, renowned above all for its medical school; Ujjain was held in high repute for astronomy, Ajanta for the teaching of art. The façade of one of the ruined buildings at Ajanta suggests the magnificence of these old universities. Nalanda, most famous of Buddhist institutions for higher learning, had been founded shortly after the Master’s death, and the state had assigned for its support the revenues of a hundred villages. It had ten thousand students, one hundred lecture-rooms, great libraries, and six immense blocks of dormitories four stories high; its observatories, said Yuan Chwang, “were lost in the vapors of the morning, and the upper rooms towered above the clouds.” The old Chinese pilgrim loved the learned monks and shady groves of Nalanda so well that he stayed there for five years. “Of those from abroad who wished to enter the schools of discussion” at Nalanda, he tells us, “the majority, beaten by the difficulties of the problem, withdrew; and those who were deeply versed in old and modern learning were admitted, only two or three out of ten succeeding.”

- The Mohammedans destroyed nearly all the monasteries, Buddhist or Brahman, in northern India. Nalanda was burned to the ground in 1197, and all its monks were slaughtered; we can never estimate the abundant life of ancient India from what these fanatics spared.

XXI : Indian Art

edit- BEFORE Indian art, as before every phase of Indian civilization, we stand in humble wonder at its age and its continuity.

- From that time to this, through the vicissitudes of five thousand years, India has been creating its peculiar type of beauty in a hundred arts. The record is broken and incomplete, not because India ever rested, but because war and the idol-smashing ecstasies of Moslems destroyed uncounted masterpieces of building and statuary, and poverty neglected the preservation of others. We shall find it difficult to enjoy this art at first sight; its music will seem weird, its painting obscure, its architecture confused, its sculpture grotesque. We shall have to remind ourselves at every step that our tastes are the fallible product of our local and limited traditions and environments; and that we do ourselves and foreign nations injustice when we judge them, or their arts, by standards and purposes natural to our life and alien to their own.

- In India the artist had not yet been separated from the artisan, making art artificial and work a drudgery; as in our Middle Ages, so, in the India that died at Plassey, every mature workman was a craftsman, giving form and personality to the product of his skill and taste. Even today, when factories replace handicrafts, and craftsmen degenerate into “hands,” the stalls and shops of every Hindu town show squatting artisans beating metal, moulding jewelry, drawing designs, weaving delicate shawls and embroideries, or carving ivory and wood. Probably no other nation known to us has ever had so exuberant a variety of arts.

- Textiles were woven with an artistry never since excelled; from the days of Cæsar to our own the fabrics of India have been prized by all the world, Sometimes, by the subtlest and most painstaking of precalculated measurements, every thread of warp and woof was dyed before being placed upon the loom; the design appeared as the weaving progressed, and was identical on either side. From homespun khaddar to complex brocades flaming with gold, from picturesque pyjamas to the invisibly-seamed shawls of Kashmir, every garment woven in India has a beauty that comes only of a very ancient, and now almost instinctive, art.

- For listening to music, in India, is itself an art, and requires long training of ear and soul.

- It is clear, from the drawings, in red pigment, of animals and a rhinoceros hunt in the prehistoric caves of Singanpur and Mirzapur, that Indian painting has had a history of many thousands of years. Palettes with ground colors ready for use abound among the remains of neolithic India. Great gaps occur in the history of the art, because most of the early work was ruined by the climate, and much of the remainder was destroyed by Moslem “idol-breakers” from Mahmud to Aurangzeb. The Vinaya Pitaka (ca. 300 B.C.) refers to King Pasenada’s palace as containing picture galleries, and Fa-Hien and Yuan Chwang describe many buildings as famous for the excellence of their murals; but no trace of these structures remains. One of the oldest frescoes in Tibet shows an artist painting a portrait of Buddha; the later artist took it for granted that painting was an established art in Buddha’s days.

- When their temples were closed or destroyed by Huns and Moslems the Hindus turned their pictorial skill to lesser forms.

- With the conversion of Ashoka to Buddhism, Indian architecture began to throw off this alien influence, and to take its inspiration and it symbols from the new religion. The transition is evident in the great capital which is all that now remains of another Ashokan pillar, at Sarnath;68 here, in a composition of astonishing perfection, ranked by Sir John Marshall as equal to “anything of its kind in the ancient world,” we have four powerful lions, standing back to back on guard, and thoroughly Persian in form and countenance; but beneath them is a frieze of well-carved figures including so Indian a favorite as the elephant, and so Indian a symbol as the Buddhist Wheel of the Law; and under the frieze is a great stone lotus, formerly mistaken for a Persian bell-capital, but now accepted as the most ancient, universal and characteristic of all the symbols in Indian art. Represented upright, with the petals turned down and the pistil or seed-vessel showing, it stood for the womb of the world; or, as one of the fairest of nature’s manifestations, it served as the throne of a god. The lotus or water-lily symbol migrated with Buddhism, and permeated the art of China and Japan. A like form, used as a design for windows and doors, became the “horseshoe arch” of Ashokan vaults and domes, originally derived from the “covered wagon” curvature of Bengali thatched roofs supported by rods of bent bamboo.

- We shall never be able to do justice to Indian art, for ignorance and fanaticism have destroyed its greatest achievements, and have half ruined the rest. At Elephanta the Portuguese certified their piety by smashing statuary and bas-reliefs in unrestrained barbarity; and almost everywhere in the north the Moslems brought to the ground those triumphs of Indian architecture, of the fifth and sixth centuries, which tradition ranks as far superior to the later works that arouse our wonder and admiration today. The Moslems decapitated statues, and tore them limb from limb; they appropriated for their mosques, and in great measure imitated, the graceful pillars of the Jain temples. Time and fanaticism joined in the destruction, for the orthodox Hindus abandoned and neglected temples that had been profaned by the touch of alien hands. We may guess at the lost grandeur of north Indian architecture by the powerful edifices that still survive in the south, where Moslem rule entered only in minor degree, and after some habituation to India had softened Mohammedan hatred of Hindu ways.

- Meanwhile Indian art had accompanied Indian religion across straits and frontiers into Ceylon, Java, Cambodia, Siam, Burma, Tibet, Khotan, Turkestan, Mongolia, China, Korea and Japan; “in Asia all roads lead from India.”

- Singhalese art began with dagobas—domed relic shrines like the stupas of the Buddhist north; it passed to great temples like that whose ruins mark the ancient capital, Anuradhapura; it produced some of the finest of the Buddha statues,108 and a great variety of objets d’art; and it came to an end, for the time being, when the last great king of Ceylon, Kirti Shri Raja Singha, built the “Temple of the Tooth” at Kandy. The loss of independence has brought decadence to the upper classes, and the patronage and taste that provide a necessary stimulus and restraint for the artist have disappeared from Ceylon.

- The final triumph of Indian architecture came under the Moguls. The followers of Mohammed had proved themselves master builders wherever they had carried their arms—at Granada, at Cairo, at Jerusalem, at Baghdad; it was to be expected that this vigorous stock, after establishing itself securely in India, would raise upon the conquered soil mosques as resplendent as Omar’s at Jerusalem, as massive as Hassan’s at Cairo, and as delicate as the Alhambra. It is true that the “Afghan” dynasty used Hindu artisans, copied Hindu themes, and even appropriated the pillars of Hindu temples, for their architectural purposes, and that many mosques were merely Hindu temples rebuilt for Moslem prayer;119 but this natural imitation passed quickly into a style so typically Moorish that one is surprised to find the Taj Mahal in India rather than in Persia, North Africa or Spain.

- The beautiful Kutb-Minar exemplifies the transition. It was part of a mosque begun at Old Delhi by Kutbu-d Din Aibak; it commemorated the victories of that bloody Sultan over the Hindus, and twenty-seven Hindu temples were dismembered to provide material for the mosque and the tower. After withstanding the elements for seven centuries the great minaret—250 feet high, built of fine red sandstone, perfectly proportioned, and crowned on its topmost stages with white marble—is still one of the masterpieces of Indian technology and art. In general the Sultans of Delhi were too busy with killing to have much time for architecture, and such buildings as they have left us are mostly the tombs that they raised during their own lifetime as reminders that even they would die. The best example of these is the mausoleum of Sher Shah at Sasseram, in Bihar; gigantic, solid, masculine, it was the last stage of the more virile Moorish manner before it softened into the architectural jewelry of the Mogul kings.

- Aurangzeb was a misfortune for Mogul and Indian art. Dedicated fanatically to an exclusive religion, he saw in art nothing but idolatry and vanity. Already Shah Jehan had prohibited the erection of Hindu temples;127 Aurangzeb not only continued the ban, but gave so economical a support to Moslem building that it, too, languished under his reign. Indian art followed him to the grave.

XXII : A Christian Epilogue

edit- IN many ways that civilization was already dead when Clive and Hastings discovered the riches of India. The long and disruptive reign of Aurangzeb, and the chaos and internal wars that followed it, left India ripe for reconquest; and the only question open to “manifest destiny” was as to which of the modernized powers of Europe should become its instrument. The French tried, and failed; they lost India, as well as Canada, at Rossbach and Waterloo. The English tried, and succeeded.

- By 1857 the crimes of the Company had so impoverished northeastern India that the natives broke out in desperate revolt. The British Government stepped in, suppressed the “mutiny,” took over the captured territories as a colony of the Crown, paid the Company handsomely, and added the purchase price to the public debt of India. It was plain, blunt conquest, not to be judged, perhaps, by Commandments recited west of Suez, but to be understood in terms of Darwin and Nietzsche: a people that has lost the ability to govern itself, or to develop its natural resources, inevitably falls a prey to nations suffering from strength and greed.

- The price of these benefactions was a financial despotism by which a race of transient rulers drained India’s wealth year by year as they returned to the reinvigorating north; an economic despotism that ruined India’s industries, and threw her millions of artisans back upon an inadequate soil; and a political despotism that, coming so soon after the narrow tyranny of Aurangzeb, broke for a century the spirit of the Indian people.

- One cannot conclude the history of India as one can conclude the history of Egypt, or Babylonia, or Assyria; for that history is still being made, that civilization is still creating. Culturally India has been reinvigorated by mental contact with the West, and her literature today is as fertile and noble as any. Spiritually she is still struggling with superstition and excess theological baggage, but there is no telling how quickly the acids of modern science will dissolve these supernumerary gods. Politically the last one hundred years have brought to India such unity as she has seldom had before: partly the unity of one alien government, partly the unity of one alien speech, but above all the unity of one welding aspiration to liberty. Economically India is passing, for better and for worse, out of medievalism into modern industry; her wealth and her trade will grow, and before the end of the century she will doubtless be among the powers of the earth.

- We cannot claim for this civilization such direct gifts to our own as we have traced to Egypt and the Near East; for these last were the immediate ancestors of our own culture, while the history of India, China and Japan flowed in another stream, and is only now beginning to touch and influence the current of Occidental life. It is true that even across the Himalayan barrier India has sent to us such questionable gifts as grammar and logic, philosophy and fables, hypnotism and chess, and above all, our numerals and our decimal system. But these are not the essence of her spirit; they are trifles compared to what we may learn from her in the future. As invention, industry and trade bind the continents together, or as they fling us into conflict with Asia, we shall study its civilizations more closely, and shall absorb, even in enmity, some of its ways and thoughts. Perhaps, in return for conquest, arrogance and spoliation, India will teach us the tolerance and gentleness of the mature mind, the quiet content of the unacquisitive soul, the calm of the understanding spirit, and a unifying, pacifying love for all living things.

The Far East

edit- The average Chinese is at once an animist, a Taoist, a Buddhist and a Confucianist.

- (IV. RELIGION WITHOUT A CHURCH)

- As India is par excellence the land of metaphysics and religion, China is by like preeminence the home of humanistic, or non-theological, philosophy.

- 5. The Pre-Confucian Philosophers

- The greatest painter of the T’ang epoch, and, by common consent, of all the Far East, rose above distinctions of school, and belonged rather to the Buddhist tradition of Chinese art. Wu Tao-tze deserved his name—Wu, Master of the Tao or Way, for all those impressions and formless thoughts which Lao-tze and Chuang-tze had found too subtle for words seemed to flow naturally into line and color under his brush.

- Will Durant and Ariel Durant, The Story of Civilization, Book I, Our Oriental Heritage (1935) (IV. PAINTING 1. Masters of Chinese Painting)

- He excelled in every subject: men, gods, devils, Buddhas, birds, beasts, buildings, landscapes—all seemed to come naturally to his exuberant art. He painted with equal skill on silk, paper, and freshly-plastered walls; he made three hundred frescoes for Buddhist edifices, and one of these, containing more than a thousand figures, became as famous in China as “The Last Judgment” or “The Last Supper” in Europe. Ninety-three of his paintings were in the Imperial Gallery in the twelfth century, four hundred years after his death; but none remains anywhere today. His Buddhas, we are told, “fathomed the mysteries of life and death”; his picture of purgatory frightened some of the butchers and fishmongers of China into abandoning their scandalously un-Buddhistic trades; his representation of Ming Huang’s dream convinced the Emperor that Wu had had an identical vision.

- Will Durant and Ariel Durant, The Story of Civilization, Book I, Our Oriental Heritage (1935) (IV. PAINTING 1. Masters of Chinese Painting)

- So great was his reputation that when he was finishing some Buddhist figures at the Hsing-shan Temple, “the whole of Chang-an” came to see him add the finishing touches. Surrounded by this assemblage, says a Chinese historian of the ninth century, “he executed the haloes with so violent a rush and swirl that it seemed as though a whirlwind possessed his hand, and all who saw it cried that some god was helping him”: the lazy will always attribute genius to some “inspiration” that comes for mere waiting. When Wu had lived long enough, says a pretty tale, he painted a vast landscape, stepped into the mouth of a cave pictured in it, and was never seen again. Never had art known such mastery and delicacy of line.

- Will Durant and Ariel Durant, The Story of Civilization, Book I, Our Oriental Heritage (1935) (IV. PAINTING 1. Masters of Chinese Painting)

- Sculpture was not one of the major arts, not even a fine art, to the Chinese. By an act of rare modesty the Far East refused to class the human body under the rubric of beauty; its sculptors played a little with drapery, and used the figures of men—seldom of women—to study or represent certain types of consciousness; but they did not glorify the body. For the most part they confined their portraits of humanity to Buddhist saints and Taoist sages, ignoring the-athletes and courtesans who gave such inspiration to the artists of Greece. In the sculpture of China animals were preferred even to philosophers and saints.

- Will Durant and Ariel Durant, The Story of Civilization, Book I, Our Oriental Heritage (1935) (II. BRONZE, LACQUER AND JADE)

- Meanwhile another influence was entering China, in the form of Buddhist theology and art. It made a home for itself first in Turkestan, and built there a civilization from which Stein and Pelliot have unearthed many tons of ruined statuary; some of it seems equal to Hindu Buddhist art at its best. The Chinese took over those Buddhist forms without much alteration, and produced Buddhas as fair as any in Gandhara or India.

- Will Durant and Ariel Durant, The Story of Civilization, Book I, Our Oriental Heritage (1935) (II. BRONZE, LACQUER AND JADE)

- One of the best of the Chinese Buddhist shrines is the Temple of the Sleeping Buddha, near the Summer Palace outside Peking; Fergusson called it “the finest architectural achievement in China.”

- Will Durant and Ariel Durant, The Story of Civilization, Book I, Our Oriental Heritage (1935) (III. PAGODAS AND PALACES)

- As Christianity transformed Mediterranean culture and art in the third and fourth centuries after Christ, so Buddhism, in the same centuries, effected a theological and esthetic revolution in the life of China. While Confucianism retained its political power, Buddhism, mingling with Taoism, became the dominating force in art, and brought to the Chinese a stimulating contact with Hindu motives, symbols, methods and forms. The greatest genius of the Chinese Buddhist school of painting was Ku K’ai-chih, a man of such unique and positive personality that a web of anecdote or legend has meshed him in.

- Will Durant and Ariel Durant, The Story of Civilization, Book I, Our Oriental Heritage (1935) (IV. PAINTING)

- He insisted on being a philosopher, too; under his portrait of the emperor he wrote: “In Nature there is nothing high which is not soon brought low. . . . When the sun has reached its noon, it begins to sink; when the moon is full it begins to wane. To rise to glory is as hard as to build a mountain out of grains of dust; to fall into calamity is as easy as the rebound of a tense spring.” His contemporaries ranked him as the outstanding man of his time in three lines: in painting, in wit, and in foolishness.

- Will Durant and Ariel Durant, The Story of Civilization, Book I, Our Oriental Heritage (1935) (IV. PAINTING)

- The Commercial Revolution of Columbus’ time cleared the routes and prepared the way for the Industrial Revolution. Discoverers refound old lands, opened up new ports, and brought to the ancient cultures the novel products and ideas of the West. Early in the sixteenth century the adventurous Portuguese, having established themselves in India, captured Malacca, sailed around the Malay Peninsula, and arrived with their picturesque ships and terrible guns at Canton (1517). “Truculent and lawless, regarding all Eastern peoples as legitimate prey, they were little if any better than . . . pirates”; and the natives treated them as such. Their representatives were imprisoned, their demands for free trade were refused, and their settlements were periodically cleansed with massacres by the frightened and infuriated Chinese.

- Will Durant and Ariel Durant, The Story of Civilization, Book I, Our Oriental Heritage (1935) (CHAPTER XXVII Revolution and Renewal)

- There were contradictions in this philosophy, but these did not disturb its leading opponent, the gentle and peculiar Wang Yang-ming. For Wang was a saint as well as a philosopher; the meditative spirit and habits of Mahayana Buddhism had sunk deeply into his soul. It seemed to him that the great error in Chu Hsi was not one of morals, but one of method; the investigation of things, he felt, should begin not with the examination of the external universe, but, as the Hindus had said, with the far profounder and more revealing world of the inner self.

- Will Durant and Ariel Durant, The Story of Civilization, Book I, Our Oriental Heritage (1935) (3. The Rebirth of Philosophy)

- When, after the fall of the Han, China found itself torn with political chaos, and life seemed lost in a welter of insecurity and war, the harassed nation turned to Buddhism as the Roman world was at the same time turning to Christianity. Taoism opened its arms to take in the new faith, and in time became inextricably mingled with it in the Chinese soul. Emperors persecuted Buddhism, philosophers complained of its superstitions, statesmen were concerned over the fact that some of the best blood of China was being sterilized in monasteries; but in the end the government found again that religion is stronger than the state; the emperors made treaties of peace with the new gods; the Buddhist priests were allowed to collect alms and raise temples, and the bureaucracy of officials and scholars was perforce content to keep Confucianism as its own aristocratic creed. The new religion took possession of many old shrines, placed its monks and fanes along with those of the Taoists on the holy mountain Tai-shan, aroused the people to many pious pilgrimages, contributed powerfully to painting, sculpture, architecture, literature, and the development of printing, and brought a civilizing measure of gentleness into the Chinese soul. Then, it, too, like Taoism, fell into decay; its clergy became corrupt, its doctrine was permeated more and more by sinister deities and popular superstitions, and its political power, never strong, was practically destroyed by the renaissance of Confucianism under Chu Hsi. Today its temples are neglected, its resources are exhausted, and its only devotees are its impoverished priests.

Nevertheless it has sunk into the national soul, and is still part of the complex but informal religion of the simpler Chinese. For religions in China are not mutually exclusive as in Europe and America, nor have they ever precipitated the country into religious wars. Normally they tolerate one another not only in the state but in the same breast; and the average Chinese is at once an animist, a Taoist, a Buddhist and a Confucianist. He is a modest philosopher, and knows that nothing is certain; perhaps, after all, the theologian may be right, and there may be a paradise; the best policy would be to humor all these creeds, and pay many diverse priests to say prayers over one’s grave. While fortune smiles, however, the Chinese citizen does not pay much attention to the gods; he honors his ancestors, but lets the Taoist and the Buddhist temples get along with the attentions of the clergy and a few women.- Will Durant and Ariel Durant, The Story of Civilization, Book I, Our Oriental Heritage (1935) (IV. RELIGION WITHOUT A CHURCH)

- Obscurity of thought and insincere inaccuracy of speech seemed to him national calamities. If a prince who was not in actual fact and power a prince should cease to be called a prince, if a father who was not a fatherly father should cease to be called a father, if an unfilial son should cease to be called a son—then men might be stirred to reform abuses too often covered up with words. Hence when Tsze-loo told Confucius, “The prince of Wei has been waiting for you, in order with you to administer the government; what will you consider the first thing to be done?” he answered, to the astonishment of prince and pupil, “What is necessary is to rectify names.”

Japan

edit- When, in 586 A.D., the Emperor Yomei died, the succession was contested in arms by two rival families, both of them politically devoted to the new creed. Prince Shotoku Taishi, who had been born, we are told, with a holy relic clasped in his infant hand, led the Buddhist faction to victory, established the Empress Suiko on the throne, and for twenty-nine years (592-621) ruled the Sacred Islands as Prince Imperial and Regent. He lavished funds upon Buddhist temples, encouraged and supported the Buddhist clergy, promulgated the Buddhist ethic in national decrees, and became in general the Ashoka of Japanese Buddhism. He patronized the arts and sciences, imported artists and artisans from Korea and China, wrote history, painted pictures, and supervised the building of the Horiuji Temple, the oldest extant masterpiece in the art history of Japan.

Despite the work of this versatile civilizer, and all the virtues inculcated or preached by Buddhism, another violent crisis came to Japan within a generation after Shotoku’s death.- (CHAPTER XXVIII The Makers of Japan)

- For the Japanese could choose among many varieties of Buddhism: he might seek self-realization and bliss through the quiet practices of Zen (“meditation”); he might follow the fiery Nichiren into the Lotus Sect, and find salvation through learning the “Lotus Law”; he might join the Spirit Sect, and fast and pray until Buddha appeared to him in the flesh; he might be comforted by the Sect of the Pure Land, and be saved by faith alone; or he might find his way in patient pilgrimage to the monastery of Koyasan, and attain paradise by being buried in ground made holy by the bones of Kobo Daishi, the great scholar, saint and artist who, in the ninth century, had founded Shingon, the Sect of the True Word.

- All in all, Japanese Buddhism was one of the pleasantest of man’s myths. It conquered Japan peacefully, and complaisantly found room, within its theology and its pantheon, for the doctrines and deities of Shinto: Buddha was amalgamated with Amaterasu, and a modest place was set apart, in Buddhist temples, for a Shinto shrine. The Buddhist priests of the earlier centuries were men of devotion, learning and kindliness, who profoundly influenced and advanced Japanese letters and arts; some of them were great painters or sculptors, and some were scholars whose painstaking translation of Buddhist and Chinese literature proved a fertile stimulus to the cultural development of Japan.

- Nakaye was a man of saintly sincerity, but his philosophy pleased neither the people nor the government. The Shogunate trembled at the notion that every man might judge for himself what was right and what was wrong.

- Our knowledge of Japanese literature is consequently fragmentary and deceptive, and our judgments of it can be of little worth. The Jesuits, harassed with these linguistic barriers, reported that the language of the islands had been invented by the Devil to prevent the preaching of the Gospel to the Japanese.

- In the year 594 the Empress Suiko, being convinced of the truth or utility of Buddhism, ordered the building of Buddhist temples throughout her realm. Prince Shotoku, who was entrusted with carrying out this edict, brought in from Korea priests, architects, wood-carvers, bronze founders, clay modelers, masons, gilders, tile-makers, weavers, and other skilled artisans. This vast cultural importation was almost the beginning of art in Japan, for Shinto had frowned upon ornate edifices and had countenanced no figures to misrepresent the gods. From that moment Buddhist shrines and statuary filled the land. The temples were essentially like those of China, but more richly ornamented and more delicately carved. Here, too, majestic torii, or gateways, marked the ascent or approach to the sacred retreat; bright colors adorned the wooden walls, great beams held up a tiled roof gleaming under the sun, and minor structures—a drum-tower, e.g., or a pagoda—mediated between the central sanctuary and the surrounding trees. The greatest achievements of the foreign artists was the group of temples at Horiuji, raised under the guidance of Prince Shotoku near Nara about the year 616. It stands to the credit of the most living of building materials that one of these wooden edifices has survived unnumbered earthquakes and outlasted a hundred thousand temples of stone; and it stands to the glory of the builders that nothing erected in later Japan has surpassed the simple majesty of this oldest shrine. Perhaps as beautiful, and only slightly younger, are the temples of Nara itself, above all the perfectly proportioned Golden Hall of the Todaiji Temple there; Nara, says Ralph Adams Cram, contains “the most precious architecture in all Asia.”

- Hideyoshi too tried to rival Kublai Khan, and built at Momoyama a “Palace of Pleasure” which his whim tore down again a few years after its completion; we may judge its magnificence from the “day long portal” removed from it to adorn the temple of Nishi-Hongwan; all day long, said its admirers, one might gaze at that carved portal without exhausting its excellence. Kano Yeitoku played Ictinus and Pheidias to Hideyoshi, but adorned his buildings with Venetian splendor rather than with Attic restraint; never had Japan, or Asia, seen such abounding decoration before.

- Buddhism stimulated art in Japan, as it had done in China; the Zen practice of meditation lent itself to brooding creativeness in color and form almost as readily as in philosophy and poetry; and visions of Amida Buddha became as frequent in Japanese art as Annunciations and Crucifixions on the walls and canvases of the Renaissance. The priest Yeishin Sozu (d. 1017) was the Fra Angelico and El Greco of this age, whose risings and descendings of Amida made him the greatest religious painter in the history of Japan.

- And though Japanese painting lacks the strength and depth of Chinese, and Japanese prints are mere poster art at their worst, and at their best the transient redemption of hurried trivialities with a national perfection of grace and line, nevertheless it was Japanese rather than Chinese painting, and Japanese prints rather than Japanese water-colors, that revolutionized pictorial art in the nineteenth century, and gave the stimulus to a hundred experiments in fresh creative forms. These prints, sweeping into Europe in the wake of reopened trade after 1860, profoundly affected Monet, Manet, Degas and Whistler; they put an end to the “brown sauce” that had been served with almost every European painting from Leonardo to Millet; they filled the canvases of Europe with sunshine, and encouraged the painter to be a poet rather than a photographer. “The story of the beautiful,” said Whistler, with the swagger that made all but his contemporaries love him, “is already complete—hewn in the marbles of the Parthenon, and broidered, with the birds, upon the fan of Hokusai—at the foot of Fuji-yama.”

- We hope that this is not quite true; but it was unconsciously true for the old Japan. She died four years after Hokusai. In the comfort and peace of her isolation she had forgotten that a nation must keep abreast of the world if it does not wish to be enslaved. While Japan carved her inro and flourished her fans, Europe was establishing a science that was almost entirely unknown to the East; and that science, built up year by year in laboratories apparently far removed from the stream of the world’s affairs, at last gave Europe the mechanized industries that enabled her to make the goods of life more cheaply—however less beautifully—than Asia’s skilful artisans could turn them out by hand. Sooner or later those cheaper goods would win the markets of Asia, ruining the economic and changing the political life of countries pleasantly becalmed in the handicraft stage. Worse than that, science made explosives, battleships and guns that could kill a little more completely than the sword of the most heroic Samurai; of what use was the bravery of a knight against the dastardly anonymity of a shell?

- Printing, like writing, came from China as part of Buddhist lore; the oldest extant examples of printing in the world are some Buddhist charms block-printed at the command of the Empress Shotoku in the year 770 A.D.

- Like most statesmen he thought of religion chiefly as an organ of social discipline, and regretted that the variety of human beliefs canceled half this good by the disorder of hostile creeds. To his completely political mind the traditional faith of the Japanese people—a careless mixture of Shintoism and Buddhism—was an invaluable bond cementing the race into spiritual unity, moral order and patriotic devotion; and though at first he approached Christianity with the lenient eye and broad intelligence of Akbar, and refrained from enforcing against it the angry edicts of Hideyoshi, he was disturbed by its intolerance, its bitter denunciation of the native faith as idolatry, and the discord which its passionate dogmatism aroused not only between the converts and the nation, but among the neophytes themselves. Finally his resentment was stirred by the discovery that missionaries sometimes allowed themselves to be used as vanguards for conquerors, and were, here and there, conspiring against the Japanese state. In 1614 he forbade the practice or preaching of the Christian religion in Japan, and ordered all converts either to depart from the country or to renounce their new beliefs. Many priests evaded the decree, and some of them were arrested. None was executed during the lifetime of Iyeyasu; but after his death the fury of the bureaucrats was turned against the Christians, and a violent and brutal persecution ensued which practically stamped Christianity out of Japan. In 1638 the remaining Christians gathered to the number of 37,000 on the peninsula of Shimabara, fortified it, and made a last stand for the freedom of worship. Iyemitsu, grandson of Iyeyasu, sent a large armed force to subdue them. When, after a three months’ siege, their stronghold was taken, all but one hundred and five of the survivors were massacred in the streets.

- Christianity had come to Japan in 1549 in the person of one of the first and noblest of Jesuits, St. Francis Xavier. The little community which he established grew so rapidly that within a generation after his coming there were seventy Jesuits and 150,000 converts in the empire. They were so numerous in Nagasaki that they made that trading port a Christian city, and persuaded its local ruler, Omura, to use direct action in spreading the new faith. “Within Nagasaki territory,” says Lafcadio Hearn, “Buddhism was totally suppressed—its priests being persecuted and driven away.” Alarmed at this spiritual invasion, and suspecting it of political designs, Hideyoshi sent a messenger to the Vice-Provincial of the Jesuits in Japan, armed with five peremptory questions

II - Life of Greece (1939)

edit

- All the problems that disturb us today—the cutting down of forests and the erosion of the soil; the emancipation of woman and the limitation of the family; the conservatism of the established, and the experimentalism of the unplaced, in morals, music, and government; the corruptions of politics and the perversions of conduct; the conflict of religion and science, and the weakening of the supernatural supports of morality; the war of the classes, the nations, and the continents; the revolutions of the poor against the economically powerful rich, and of the rich against the politically powerful poor; the struggle between democracy and dictatorship, between individualism and communism, between the East and the West—all these agitated, as if for our instruction, the brilliant and turbulent life of ancient Hellas. There is nothing in Greek civilization that does not illuminate our own.

- Preface, P.18

- We do not know which of the many roads to decay Crete chose; perhaps she took them all. Her once famous forests of cypress and cedar vanished; today two thirds of the island are a stony waste, incapable of holding the winter rains. Perhaps there too, as in most declining cultures, population control went too far, and reproduction was left to the failures. Perhaps, as wealth and luxury increased, the pursuit of physical pleasure sapped the vitality of the race, and weakened its will to live or to defend itself; a nation is born stoic and dies epicurean

- Ch. I Crete, Section IV The Fall of Cnossus, P.51

- The Argives ascribed the foundation of their city to Pelasgic Argus, the hero with a hundred eyes; and its first flourishing to an Egyptian, Danaus, who came at the head of a band of “Danaae” and taught the natives to irrigate their fields with wells. Such eponyms are not to be scorned; the Greeks preferred to end with myth that infinite regress which we must end with mystery.

- Ch. IV Sparta, Section II Argos, P. 116

- Apparently the legislators felt that to alter certain customs, or to establish new ones, the safest procedure would be to present their proposals as commands of the god; it was not the first time that a state had laid its foundations in the sky.

- Ch. IV Sparta, Section III Laconia, 4. The Lacedaemonian Constitution P. 123

- When an advanced thinker asked Lycurgus to establish a democracy Lycurgus replied, “Begin, my friend, by setting it up in your own family.”

- Ch. IV Sparta, Section III Laconia, 4. The Lacedaemonian Constitution P. 125

- If such arrangements [by the parents to try to find a mate for their children] left some adults still unmarried, several men might be pushed into a dark room with an equal number of girls, and be left to pick their life mates in the darkness; the Spartans thought that such choosing would not be blinder than love.

- Ch. IV Sparta, Section III Laconia, 5. The Spartan Code P. 129

- The Spartans themselves were forbidden to go abroad without permission of the government, and to dull their curiosity they were trained to a haughty exclusiveness that would not dream that other nations could teach them anything. The system had to be ungracious in order to protect itself; a breath from that excluded world of freedom, luxury, letters, and arts might topple over this strange and artificial society, in which two thirds of the people were serfs, and all the masters were slaves.

- Ch. IV Sparta, Sec III Laconia, 5. The Spartan Code P. 131

- A luxury-loving Sybarite remarked of the Spartans that “it was no commendable thing in them to be so ready to die in the wars, since by that they were freed from much hard labor and miserable living.” Health was one of the cardinal virtues in Sparta, and sickness was a crime; Plato’s heart must have been gladdened to find a land so free from medicine and democracy.

- Ch. IV Sparta, Sec III Laconia, 6. An Estimate of Sparta, P. 132

- Self-control, moderation, equanimity in fortune and adversity— qualities that the Athenians wrote about but seldom showed—were taken for granted in every Spartan citizen.

- Ch. IV Sparta, Sec III Laconia, 6. An Estimate of Sparta, P. 132

- Like Plato and Plutarch, Xenophon was never tired of praising Spartan ways. Here it was, of course, that Plato found the outlines of his Utopia, a little blurred by a strange indifference to Ideas. Weary and fearful of the vulgarity and chaos of democracy, many Greek thinkers took refuge in an idolatry of Spartan order and law. They could afford to praise Sparta, since they did not have to live in it. They did not feel at close range the selfishness, coldness, and cruelty of the Spartan character; they could not see from the select gentlemen whom they met, or the heroes whom they commemorated from afar, that the Spartan code produced good soldiers and nothing more; that it made vigor of body a graceless brutality because it killed nearly all capacity for the things of the mind.

- Ch. IV Sparta, Sec III Laconia, 6. An Estimate of Sparta, P. 132-133

- Greek travelers marveled at a life so simple and unadorned, a franchise so jealously confined, a conservatism so tenacious of every custom and superstition, a courage and discipline so exalted and limited, so noble in character, so base in purpose, and so barren in result; while, hardly a day’s ride away, the Athenians were building, out of a thousand injustices and errors, a civilization broad in scope and yet intense in action, open to every new idea and eager for intercourse with the world, tolerant, varied, complex, luxurious, innovating, skeptical, imaginative, poetical, turbulent, free. It was a contrast that would color and almost delineate Greek history.

- Ch. IV Sparta, Sec III Laconia, 6. An Estimate of Sparta, P. 133

- In the end Sparta’s narrowness of spirit betrayed even her strength of soul. She descended to the sanctioning of any means to gain a Spartan aim; at last she stooped so far to conquer as to sell to Persia the liberties that Athens had won for Greece at Marathon. Militarism absorbed her, and made her, once so honored, the hated terror of her neighbors. When she fell, all the nations marveled, but none mourned. Today, among the scanty ruins of that ancient capital, hardly a torso or a fallen pillar survives to declare that here there once lived Greeks.

- Ch. IV Sparta, Sec III Laconia, 6. An Estimate of Sparta, P. 133

- Perhaps time and chance were ungrateful to the city [Corinth], and her annals fell to be written by men of other loyalties. The past would be startled if it could see itself in the pages of historians.

- Ch. IV Sparta, Sec V Corinth, P.138

- Theognis lived through these revolutions, and described them in bitter poems that might be the voice of our class war today... He warns that the injustices of the aristocracy may provoke a revolution: (Ch. IV Sparta, Sec VI Megara, P.138-140)

Our state is pregnant, shortly to produce / A rude avenger of prolonged abuse. The commons hitherto seem sober-minded / But their superiors are corrupt and blinded. The rule of noble spirits, brave and high / Never endangered peace and harmony. The supercilious, arrogant pretense / Of feeble minds, weakness and insolence; Justice and truth and law wrested aside / By crafty shifts of avarice and pride; These are our ruin, Cyrnus!—never dream /(Tranquil and undisturbed as it may seem) Of future peace or safety to the state / Bloodshed and strife will follow soon or late.

- In the end we find him [Theognis] back in Megara, old and broken, and promising, for safety’s sake, never again to write of politics. He consoles himself with wine and a loyal wife, and does his best to learn at last the lesson that everything natural is forgivable. (Ch. IV Sparta, Sec VI Megara, P.141)

Learn, Cyrnus, learn to bear an easy mind; Accommodate your humor to mankind And human nature; take it as you find. A mixture of ingredients good and bad— Such are we all, the best that can be had. The best are found defective, and the rest, For common use, are equal to the best. Suppose it had been otherwise decreed, How could the business of the world proceed?

- Today such patients [pilgrims looking for healing] go to Tenos in the Cyclades, where the priests of the Greek Church heal them as those of Asclepius healed their forerunners two thousand five hundred years ago. And the gloomy peak where once the people of Epidaurus sacrificed to Zeus and Hera is now the sacred mount of St. Elias. The gods are mortal, but piety is everlasting.

- Ch. IV Sparta, Sec VI Aegina and Epidaurus, P.143

- Homer was a poet, and knew that one touch of beauty redeems a multitude of sins; Hesiod [the poor poet] was a peasant who grudged the cost of a wife, and grumbled at the impudence of women who dared to sit at the same table with their husbands. Hesiod, with rough candor, shows us the ugly basement of early Greek society—the hard poverty of serfs and small farmers upon whose toil rested all the splendor and war sport of the aristocracy and the kings. Homer sang of heroes and princes for lords and ladies; Hesiod knew no princes, but sang his lays of common men, and pitched his tune accordingly. In his verses we hear the rumblings of those peasant revolts that would produce in Attica the reforms of Solon and the dictatorship of Peisistratus.

- Ch. V Athens, Sec I Hesiod's Boeotia, P. 151

- In this region [on the Boeotian Coast] once lived an insignificant tribe, the Graii, who joined the Euboeans in sending a colony to Cumae, near Naples; from them the Romans gave to all the Hellenes whom they encountered the name Graici, Greeks; and from that circumstance all the world came to know Hellas by a term which its own inhabitants never applied to themselves.

- Ch. V Athens, Sec III The Lesser States, P. 156

- By this piecemeal revolution the royal office was shorn of all its powers, and its holder was confined to the functions of a priest. The word king remained in the Athenian constitution to the end of its ancient history, but the reality was never restored. Institutions may with impunity be altered or destroyed from above if their names are left unchanged.

- Ch. V Athens, Sec IV Attica, 2. Athens Under the Oligarchs, P. 159

- Meanwhile, in the towns, the middle classes, unhindered by law, were reducing the free laborers to destitution, and gradually replacing them with slaves. Muscle became so cheap that no one who could afford to buy it deigned any longer to work with his hands; manual labor became a sign of bondage, an occupation unworthy of freemen. The landowners, jealous of the growing wealth of the merchant class, sold abroad the corn [grain] that their tenants needed for food, and at last, under the law of debt, sold the Athenians themselves.

- Ch. V Athens, Sec IV Attica, 2. Athens Under the Oligarchs, P. 160-161