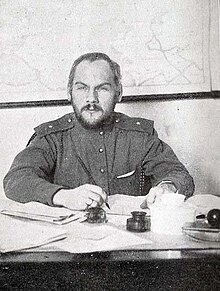

Nikolai Krylenko

Russian revolutionary, politician and chess organiser (1885-1938)

Nikolai Vasilyevich Krylenko (Russian: Никола́й Васи́льевич Крыле́нко, IPA: [krɨˈlʲenkə]; May 2, 1885 – July 29, 1938) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary and Soviet politician. Krylenko served in a variety of posts in the Soviet legal system, rising to become People's Commissar for Justice and Prosecutor General of the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic.

Quotes

edit- We are sometimes up against a flat refusal to apply this law rigidly. One People's Judge told me flatly that he could never bring himself to throw someone in jail for stealing four ears. What we're up against here is a deep prejudice, imbibed with their mother's milk... a mistaken belief that people should be tried in accordance not with the Party's political guidelines but with considerations of "higher justice".

- Krylenko criticizing the leniency of some Soviet officials who objected to the infamous "five ears law". Quoted in Edvard Radzinsky, Stalin: The First In-Depth Biography Based on Explosive New Documents from Russia's Secret Archives, page 258.

- We must finish once and for all with the neutrality of chess. We must condemn once and for all the formula "chess for the sake of chess", like the formula "art for art's sake". We must organize shockbrigades of chess-players, and begin immediate realization of a Five-Year Plan for chess.

- Krylenko on promoting chess in the Soviet Union. Quoted in Robert Conquest, The Great Terror: A Reassessment

- So who are the bulk of our clients in these sorts of cases? Is it the working class? No! It's classless hoodlums. Classless hoodlums, either from the dregs of the society, or from the remains of the exploiters' class. They have no place to go. So they take to -- pederasty. Together with them, next to them, under this excuse, in stinky secretive bordellos another kind of activity takes place as well -- counter-revolutionary work.

- Krylenko on the law re-criminalizing homosexuality in 1936. Quoted in David Tuller, Cracks in the Iron Closet: Travels in Gay and Lesbian Russia, University of Chicago Press, 1996

- After two decades of building socialism in the USSR there is no reason for anybody to be a homosexual.

- Krylenko on the law re-criminalizing homosexuality in 1936. Quoted in David Tuller, Cracks in the Iron Closet: Travels in Gay and Lesbian Russia, University of Chicago Press, 1996

- The basic mistake in eyery case is made by those women who consider 'freedom of abortion' as one of their civil rights. We need new fighters - they built this life, we need people.

- On penalizing abortion in 1936. Quoted in Wendy Z. Goldman, Women, the State and Revolution: Soviet Family Policy and Social Life, 1917-1936. Cambridge Russian, Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies, 1993

- We will secure peace, over the corpses of the counterrevolutionary command staff if necessary.

- Krylenko after being named commander-in-chief on the Russian Army in November 1917. Quoted in Brian Taylor, Politics and the Russian Army: Civil-Military Relations, 1689-2000

- In the absence of a criminal code, a court might give a reprimand for a punch in the nose in Ryazan, while the sentence in Tula might be shooting.

- Krylenko on the importance of having a universal criminal code, quoted in Yuri Feofanov & Donald D. Barry, Politics and Justice in Russia: Major Trials of the Post-Stalin Era

Quotes about Krylenko

edit- An epileptic degenerate . . . and the most repulsive type I came across in all my connections with the Bolsheviks.

- Bruce Lockhart, Memoirs of a British Agent. Book IV. Chapter 5.

- Krylenko is brave and fearless. He is one of the typical Russians of whom the great psychologist Dostoyevsky said: "it is not he that created the idea, but the idea that created him."

- Russkoye Slovo newspaper, ENSIGN KRYLENKO THAMES STAR, VOLUME LII, ISSUE 18643, 8 MARCH 1918

- The Bolsheviks had already orchestrated several 'show trials.' The Cheka had staged the 'Trial of the St. Petersburg Combat Organization'; its successor, the new GPU, the 'Trial of the Socialist Revolutionaries.' In these and other such farces, defendants were inevitably sentenced to death or to long prison terms in the north. The Cieplak show trial is a prime example of Bolshevik revolutionary justice at this time. Normal judicial procedures did not restrict revolutionary tribunals at all; in fact, the prosecutor N.V. Krylenko, stated that the courts could trample upon the rights of classes other than the proletariat. Appeals from the courts went not to a higher court, but to political committees. Western observers found the setting -- the grand ballroom of a former Noblemen's Club, with painted cherubs on the ceiling -- singularly inappropriate for such a solemn event. Neither judges nor prosecutors were required to have a legal background, only a proper 'revolutionary' one. That the prominent 'No Smoking' signs were ignored by the judges themselves did not bode well for legalities.

- Father Christopher Lawrence Zugger, "The Forgotten: Catholics in the Soviet Empire from Lenin through Stalin," University of Syracuse Press, 2001. Page 182.

- Krylenko, who began to speak at 6:10 PM, was moderate enough at first, but quickly launched into an attack on religion in general and the Catholic Church in particular. "The Catholic Church", he declared, "has always exploited the working classes." When he demanded the Archbishop's death, he said, "All the Jesuitical duplicity with which you have defended yourself will not save you from the death penalty. No Pope in the Vatican can save you now." As the long oration proceeded, the Red Procurator worked himself into a fury of anti-religious hatred. "Your religion", he yelled, "I spit on it, as I do on all religions, -- on Orthodox, Jewish, Mohammedan, and the rest." "There is no law here but Soviet Law," he yelled at another stage, "and by that law you must die.

- New York Herald correspondent Francis MacCullagh: The Bolshevik Persecution of Christianity, E.P. Dutton and Company, 1924. Page 221.

- Under the communist dictatorship of Lenin and then Stalin, Krylenko (1885-1938) rose through the Soviet Union’s legal system to become People’s Commissar for Justice and a Prosecutor General. He was a leading practitioner of the theory of “socialist legality,” which held that an accused person’s innocence or guilt depended on that person’s politics (real or imagined). It sounds nuts and indeed, it was. It was the stuff of Orwell’s nightmare, and one of the reasons the Soviet Union thankfully perished of its own poison.

- Lawrence Reed, Judge Amy Coney Barrett and the Krylenko Test, Foundation For Economic Education, 14 October 2020

- In The Gulag Archipelago, the famous Soviet dissident and Nobel laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn recounted an episode involving Krylenko. Shortly after Lenin’s Bolsheviks assumed power in 1917, an admiral named Shchastny was sentenced by one of the regime’s judges “to be shot within 24 hours.” When some in the courtroom expressed shock, it was Krylenko who responded thusly: “What are you worrying about? Executions have been abolished. But Shchastny is not being executed; he is being shot.”

- Lawrence Reed, Judge Amy Coney Barrett and the Krylenko Test, Foundation For Economic Education, 14 October 2020

- The Vatican, Germany, Poland, Great Britain, and the United States undertook frantic efforts to save the Archbishop and his chancellor. In Moscow, the ministers from the Polish, British, Czechoslovak, and Italian missions appealed 'on the grounds of humanity,' and Poland offered to exchange any prisoner to save the archbishop and the monsignor. Finally, on March 29, the Archbishop's sentence was commuted to ten years in prison, ... but the Monsignor was not to be spared. Again, there were appeals from foreign powers, from Western Socialists and Church leaders alike. These appeals were for naught: Pravda editorialized on March 30 that the tribunal was defending the rights of the workers, who had been oppressed by the bourgeois system for centuries with the aid of priests. Pro-Communist foreigners who intervened for the two men were also condemned as 'compromisers with the priestly servants of the bourgeoisie.' ...Father Rutkowski recorded later that Budkiewicz surrendered himself over to the will of God without reservation. On Easter Sunday, the world was told that the Monsignor was still alive, and Pope Pius XI publicly prayed at St. Peter's that the Soviets would spare his life. Moscow officials told foreign ministers and reporters that the Monsignor's sentence was just, and that the Soviet Union was a sovereign nation that would accept no interference. In reply to an appeal from the rabbis of New York City to spare Budkiewicz's life, Pravda wrote a blistering editorial against 'Jewish bankers who rule the world' and bluntly warned that the Soviets would kill Jewish opponents of the Revolution as well. Only on April 4 did the truth finally emerge: the Monsignor had already been in the grave for three days. When the news came to Rome, Pope Pius fell to his knees and wept as he prayed for the priest's soul. To make matters worse, Cardinal Gasparri had just finished reading a note from the Soviets saying that 'everything was proceeding satisfactorily' when he was handed the telegram announcing the execution. On March 31, 1923, Holy Saturday, at 11:30 PM, after a week of fervent prayers and a firm declaration that he was ready to be sacrificed for his sins, Monsignor Constantine Budkiewicz had been taken from his cell and, sometime before the dawn of Easter Sunday, shot in the back of the head on the steps of the Lubyanka prison.

- Father Christopher Lawrence Zugger, "The Forgotten: Catholics in the Soviet Empire from Lenin through Stalin," University of Syracuse Press, 2001. Page 182.

- Offering me a seat, Krylenko said: "I have no doubt that you personally are not guilty of anything. We are both performing our duty to the Party—I have considered and consider you a Communist. I will be the prosecutor at the trial; you will confirm the testimony given during the investigation. This is our duty to the Party, yours and mine. Unforeseen complications may arise at the trial. I will count on you. If the need should arise, I will ask the presiding judge to call on you. And you will find the right words.

- Mikhail Yakubovich, a defendant in one of the show trials, describing a meeting with Krylenko after weeks of torture by the OGPU to discuss his upcoming trial. Quoted in Medvedev, Roy; George Shriver (1990). Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism

- Comrade Krylenko concerns himself only incidentally with the affairs of his commissariat. But to direct the Commissariat of Justice, great initiative and a serious attitude toward oneself is required. Whereas Comrade Krylenko used to spend a great deal of time on mountain-climbing and traveling, now he devotes a great deal of time to playing chess... We need to know what we are dealing with in the case of Comrade Krylenko—the commissar of justice? or a mountain climber? I don't know which Comrade Krylenko thinks of himself as, but he is without doubt a poor people's commissar.

- Mir Jafar Baghirov's speech at the Supreme Soviet in January 1938, that pricipitated Krylenko's downfall. Quoted from the official protocols published in 1938 by Roy A. Medvedev in "New Pages from the Political Biography of Stalin"