Existence of God

The existence of God is a subject of debate in theology, the philosophy of religion, and popular culture.[1] A wide variety of arguments for and against the existence of God can be categorized as logical, empirical, metaphysical, subjective or scientific. In philosophical terms, the question of the existence of God involves the disciplines of epistemology (the nature and scope of knowledge) and ontology (study of the nature of being or existence) and the theory of value (since some definitions of God include "perfection").

Newer rites of grace prevail;

Faith for all defects supplying,

Where the feeble senses fail.

A

edit- Quotations listed alphabetically by author or work.

- The existence of God may be proved in five ways. The first and most manifest way is the argument from motion. ...Whatever is in motion is moved by another, for nothing can be in motion except it have a potentiality for that toward which it is being moved. ...It is ...impossible that from the same point of view and in the same way anything should be both moved and mover, or that it should move itself. Therefore, whatever is in motion must be put in motion by another. If that by which it is put in motion be itself put in motion, then this also must needs be put in motion by another, and that by another again. This cannot go on to infinity, because then there would be no first mover; as the staff only moves because it is put into motion by the hand. Therefore it is necessary to arrive at a First Mover, put in motion by no other; and this everyone understands to be God.

- The second way is from the nature of the efficient cause. In the world of sense we find there is an order of efficient causes. There is no case known (neither is it, indeed, possible) in which a thing is found to be the efficient cause of itself; for so it would be prior to itself, which is impossible. Now in efficient causes it is not possible to go on to infinity, because in all efficient causes following in order, the first is the cause of the intermediate cause, and the intermediate is the cause of the ultimate cause, whether the intermediate cause be several, or only one. Now to take away the cause is to take away the effect. Therefore, if there be no first cause among efficient causes, there will be no ultimate, nor any intermediate cause. But if in efficient causes it is possible to go on to infinity, there will be no first efficient cause, neither will there be an ultimate effect, nor any intermediate efficient causes; all of which is plainly false. Therefore it is necessary to admit a first efficient cause, to which everyone gives the name of God.

- The third way is taken from possibility and necessity, and runs thus. We find in nature things that are possible to be and not to be, since they are found to be generated, and to corrupt, and consequently, they are possible to be and not to be. But it is impossible for these always to exist, for that which is possible not to be at some time is not. Therefore, if everything is possible not to be, then at one time there could have been nothing in existence. Now if this were true, even now there would be nothing in existence, because that which does not exist only begins to exist by something already existing. Therefore, if at one time nothing was in existence, it would have been impossible for anything to have begun to exist; and thus even now nothing would be in existence � which is absurd. Therefore, not all beings are merely possible, but there must exist something the existence of which is necessary. But every necessary thing either has its necessity caused by another, or not. Now it is impossible to go on to infinity in necessary things which have their necessity caused by another, as has been already proved in regard to efficient causes. Therefore we cannot but postulate the existence of some being having of itself its own necessity, and not receiving it from another, but rather causing in others their necessity. This all men speak of as God.

- The fourth way is taken from the gradation to be found in things. Among beings there are some more and some less good, true, noble and the like. But "more" and "less" are predicated of different things, according as they resemble in their different ways something which is the maximum, as a thing is said to be hotter according as it more nearly resembles that which is hottest; so that there is something which is truest, something best, something noblest and, consequently, something which is uttermost being; for those things that are greatest in truth are greatest in being, as it is written in Metaph. ii. Now the maximum in any genus is the cause of all in that genus; as fire, which is the maximum heat, is the cause of all hot things. Therefore there must also be something which is to all beings the cause of their being, goodness, and every other perfection; and this we call God.

- The fifth way is taken from the governance of the world. We see that things which lack intelligence, such as natural bodies, act for an end, and this is evident from their acting always, or nearly always, in the same way, so as to obtain the best result. Hence it is plain that not fortuitously, but designedly, do they achieve their end. Now whatever lacks intelligence cannot move towards an end, unless it be directed by some being endowed with knowledge and intelligence; as the arrow is shot to its mark by the archer. Therefore some intelligent being exists by whom all natural things are directed to their end; and this being we call God.

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica (1265–1274) I, Q.2, Art. 3, Obj. 2 in The "Summa Theologica" of St. Thomas Aquinas (1911) Tr. Fathers of the English Dominican Province, Vol. 1, pp. 24-25.

- Even theologians — even the great theologians of the thirteenth century,— even Saint Thomas Aquinas himself — did not trust to faith alone, or assume the existence of God.

- Henry Adams, Mont Saint Michel and Chartres (1904), Chapter III The Merveille

- Simply believing in the existence of God is not exactly what I would call a commitment. After all, even the devil believes that God exists! Believing has to change the way we live.

- Mother Angelica, Mother Angelica's Answers, Not Promises.

B

edit- Infinite God, age after age, throughout all cycles, wills through His Infinite Mercy to effect His presence amidst mankind by stooping down to human level in the human form, but His physical presence amidst mankind not being apprehended, He is looked upon as an ordinary man of the world. When He asserts, however, His Divinity on earth by proclaiming Himself the Avatar of the Age, He is worshipped by some who accept Him as God; and glorified by a few who know him as God on Earth. But it invariably falls to the lot of the rest of humanity to condemn Him, while He is physically in their midst.

Thus it is that God as man, proclaiming Himself as the Avatar, suffers Himself to be persecuted and tortured, to be humiliated and condemned by humanity for whose sake His Infinite Love has made him stoop so low, in order that humanity, by its very act of condemning God's manifestation in the form of Avatar should, however, indirectly, assert the existence of God in His Infinite Eternal state.- Meher Baba, The Highest of the High (1953)

- Debates about the existence of God are interminable (...) In my view, though, the persistence of this debate is not surprising for one reason only: the depth of the widespread human need to cope with the harsh realities of the human predicament, including but not limited to the fact that our lives are meaningless in important ways. Upton Sinclair famously remarked that it “is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.” It is similarly difficult to get somebody to understand something when the meaning of his life depends on his not understanding it.

- David Benatar, Meaninglessness, p. 39

- Many people today lack hope. They are perplexed by the questions that present themselves ever more urgently in a confusing world, and they are often uncertain which way to turn for answers. They see poverty and injustice and they long to find solutions. They are challenged by the arguments of those who deny the existence of God and they wonder how to respond... Where can we look for answers? The Spirit points us towards the way that leads to life, to love and to truth. The Spirit points us towards Jesus Christ. In him we find the answers we are seeking.

- Pope Benedict XVI, Young Pilgrims (13 July 2008)

- Truly says Cudworth that the greatest ignorance of which our modern wiseacres accuse the ancients is their belief in the soul’s immortality. Like the old skeptic of Greece, our scientists—to use an expression of the same Dr. Cudworth—are afraid that if they admit spirits and apparitions they must admit a God too; and there is nothing too absurd, he adds, for them to suppose, in order to keep out the existence of God. The great body of ancient materialists, skeptical as they now seem to us, thought otherwise, and Epicurus, who rejected the soul's immortality, believed still in a God, and Demokritus fully conceded the reality of apparitions. The preexistence and God-like powers of the human spirit were believed in by most all the sages of ancient days. (251)

- H. P. Blavatsky, Isis Unveiled, The Veil of Isis, Part 1, Science, (1877)

- They had all been things, not people, to each other, which after all is the only sensible and fruitful attitude in a thing-dominated world. (Except, of course, for Father Domenico, whose desire to prevent anybody from accomplishing anything, chiefly by wringing his hands, had to be written off as the typical, incomprehensible attitude of the mystic—a howling anachronism in the modern world, and predictably ineffectual.) And in point of fact none of them—not even Father Domenico—could fairly be said to have failed. Instead, they had all been betrayed. Their plans and operations had all depended implicitly upon the existence of God—even Jack, who had entered Positano as an atheist, had been reluctantly forced to grant that—and in the final pinch, He had turned out to have been not around any more after all. If this shambles was anyone’s fault, it was His.

- James Blish, The Day After Judgment (1971), Introductory section The Wrath-Bearing Tree (p. 23)

- Marx denied the existence of God but turned over all His functions to History, which is inevitably directed to a goal fulfilling of man and which takes the place of Providence. One might as well be a Christian if one is so naive.

- Alian Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind, p. 196.

- My experiences with science led me to God. They challenge science to prove the existence of God. But must we really light a candle to see the sun?

- Wernher von Braun from a letter to the California State board of Education (14 September 1972)

C

edit- Ivan Karamazov ... does not absolutely deny the existence of God. He refutes Him in the name of a moral value. ... God, in His turn, is put on trial. If evil is essential to divine creation, then creation is unacceptable. Ivan will no longer have recourse to this mysterious God, but to a higher principle – namely, justice. He launches the essential undertaking of rebellion, which is that of replacing the reign of grace by the reign of justice.

- Albert Camus on Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Rebel, A. Bower, trans. (1956), pp. 55-56

- [On the existence of God] No. No, there's no God, but there might be some sort of an organizing intelligence, and I think to understand it is way beyond our ability. It's certainly not a judgmental entity. It's certainly not paternalistic and all these qualities that have been attributed to God. It's probably a dispassionate... That's why I say, "Suppose He doesn't give a shit? Suppose there is a God but He just doesn't give a shit?" That's the kind of thing that might be at work.

- George Carlin, The Onion A.V. Club, September 6, 2000 [1]

- Of course I doubt [the existence of God], I would distrust anybody who didn't doubt. But I'm a believer. I have an understanding and belief in the divinity of things. It seems to me that people look at God in the wrong way. They think that God is there to serve them, but it's the other way around. God isn't some kind of cosmic bell-boy to be called upon to sort things out for us. It's important for us to realise that God has given us the potential to sort things out on our own.

- Nick Cave, Observer (May, 1998)

- Only if you admit the existence of god does everything become meaningful. When we bring God into our lives, distinctions lessen and we feel that all people are our own. On the physical plane there is a difference between myself and others, but on the spiritual plane we are the same Satchidananda (Existence-Consciousness-Bliss Absolute). From that standpoint no one can help another—one is only helping oneself. The key to our philanthropy is this: In doing good to others, we try to forget the apparent distinctions between ourselves and other people. The welfare of others is my welfare—that is our attitude. Who does not want his own good? If you believe in God and serve society, you can never feel any resentment....People may get social merit through philanthropic activities, but if their egos are involved in those activities, they will not get any spiritual merit. Even the result of a good action turns into a bondage if it is done with ego. On the other hand, unselfish actions destroys the bondage of action and bring literation to humanity. (p.430)

- Swami Adbhutananda, God Lived with Them, Advaita Ashrama, 1998. In reply to western ladies who said that one should give higher place to philanthropy than to God.

- The dogmas we really hold are far more fantastic, and, perhaps, far more beautiful than we think. In the course of these essays I fear that I have spoken from time to time of rationalists and rationalism, and that in a disparaging sense. Being full of that kindliness which should come at the end of everything, even of a book, I apologize to the rationalists even for calling them rationalists. There are no rationalists. We all believe fairy-tales, and live in them. Some, with a sumptuous literary turn, believe in the existence of the lady clothed with the sun. Some, with a more rustic, elvish instinct, like Mr. McCabe, believe merely in the impossible sun itself. Some hold the undemonstrable dogma of the existence of God; some the equally undemonstrable dogma of the existence of the man next door.

- G. K. Chesterton, in Heretics (1905), Chapter XX : Concluding Remarks on the Importance of Orthodoxy

- He held that philosophy should be kept separate from theology, not intimately blended with it as in scholasticism. He accepted orthodox religion... But while he thought that reason could show the existence of God, he regarded everything else in theology as known only by revelation. Indeed he held that the triumph in faith is greatest when to the unaided reason a dogma appears most absurd. Philosophy, however, should depend only upon reason. He was thus an advocate of the doctrine of "double truth," that of reason and that of revelation.

- G. K. Chesterton, in A History of Western Philosophy, Chapter VII. Francis Bacon, p. 542.

- A characteristic of Locke, which descended from him to the whole Liberal movement, is lack of dogmatism. Some few certainties he takes over from his predecessors: our own existence, the existence of God, and the truth of mathematics. But wherever his doctrines differ from his forerunners, they are to the effect that truth is hard to ascertain, and that a rational man will hold his opinions with some measure of doubt. This temper of mind is obviously connected with religious toleration, with the success of parliamentary democracy, with laissez-faire, and with the whole system of liberal maxims.

- G. K. Chesterton, in A History of Western Philosophy, Chapter XIII. Locke's Theory of Knowledge, p. 606.

- The strongest saints and the strongest sceptics alike took positive evil as the starting-point of their argument. If it be true (as it certainly is) that a man can feel exquisite happiness in skinning a cat, then the religious philosopher can only draw one of two deductions. He must either deny the existence of God, as all atheists do; or he must deny the present union between God and man, as all Christians do. The new theologians seem to think it a highly rationalistic solution to deny the cat.

- G. K. Chesterton, in Orthodoxy (book), Chapter II. "The Maniac"

- Men who begin to fight the Church for the sake of freedom and humanity end by flinging away freedom and humanity if only they may fight the Church. This is no exaggeration; I could fill a book with the instances of it. Mr. Blatchford set out, as an ordinary Bible-smasher, to prove that Adam was guiltless of sin against God; in manoeuvring so as to maintain this he admitted, as a mere side issue, that all the tyrants, from Nero to King Leopold, were guiltless of any sin against humanity. I know a man who has such a passion for proving that he will have no personal existence after death that he falls back on the position that he has no personal existence now. He invokes Buddhism and says that all souls fade into each other; in order to prove that he cannot go to heaven he proves that he cannot go to Hartlepool. I have known people who protested against religious education with arguments against any education, saying that the child's mind must grow freely or that the old must not teach the young. I have known people who showed that there could be no divine judgment by showing that there can be no human judgment, even for practical purposes. They burned their own corn to set fire to the church; they smashed their own tools to smash it; any stick was good enough to beat it with, though it were the last stick of their own dismembered furniture. We do not admire, we hardly excuse, the fanatic who wrecks this world for love of the other. But what are we to say of the fanatic who wrecks this world out of hatred of the other? He sacrifices the very existence of humanity to the non-existence of God. He offers his victims not to the altar, but merely to assert the idleness of the altar and the emptiness of the throne. He is ready to ruin even that primary ethic by which all things live, for his strange and eternal vengeance upon some one who never lived at all.

- G. K. Chesterton, in Orthodoxy (book), Chapter VIII. "The Romances of Orthodoxy"

- I am not here to tell you that defeat is part of life: we all know that. Only the defeated know Love. Because it is in the realm of love that we fight our first battles and generally lose. I am here to tell you that there are people who have never been defeated. They are the ones who never fought... They managed to avoid scars, humiliations, a sense of helplessness, as well as those moments when even warriors doubt the existence of God.

- Paulo COelho, Manuscript Found in Accra, The Defeated Ones

- Reason alone cannot prove the existence of God. Faith is reason plus revelation, and the revelation part requires one to think with the spirit as well as with the mind. You have to hear the music, not just read the notes on the page.

- Let's say that you have an incredible one percent of all the knowledge in the universe. Would it be possible, in the ninety-nine percent of the knowledge that you haven't yet come across, that there might be ample evidence to prove the existence of God? If you are reasonable, you will be forced to admit that it is possible.

- Ray Comfort, God doesn't believe in atheists (2002)

- What can we say about metaphysical naturalism? Again, I want to make two points.

- My arguments for the existence of God show that metaphysical naturalism is not true. There is a personal, transcendent reality beyond the physical universe.

- Secondly, I think that metaphysical naturalism is so contrary to reason and experience as to be absurd.

- In the following arguments, the first premise in every case is taken from Dr. Rosenberg’s own book.

- First is the argument from intentionality:

- According to Dr. Rosenberg, if naturalism is true then I cannot think about anything. That is because there are no intentional states.

- But I am thinking about naturalism. From which it follows,

- Therefore, naturalism is not true.

- So, if you think that you ever think about anything you should conclude that naturalism is false.

- Second is the argument from meaning:

- According to Dr. Rosenberg, if naturalism is true then no sentence has any meaning. And he says that all the sentences in his own book are in fact meaningless.

- But, premise (1) has meaning. We all understood it.

- Therefore, naturalism is not true.

- Third is the argument from truth:

- According to Dr. Rosenberg, if naturalism is true then there are no true sentences. That is because they are all meaningless.

- But, premise (1) is true. That is what the naturalist believes and asserts.

- Therefore, naturalism is not true.

- Fourth is the argument from moral praise and blame:

- According to Dr. Rosenberg, if naturalism is true then I am not morally praiseworthy or blameworthy for any of my actions because, as I said, on his view objective moral values and duties do not exist.

- But, I am morally praiseworthy and blameworthy for at least some of my actions. If you think that you have ever done something truly wrong or truly good then you should conclude:

- Therefore, naturalism is not true.

- Fifth is the argument from freedom:

- According to Dr. Rosenberg, if naturalism is true then I do not do anything freely. Everything is determined.

- But, I can freely agree or disagree with premise (1). From which it follows:

- Therefore, naturalism is not true.

- Sixth is the argument from purpose:

- According to Dr. Rosenberg, if naturalism is true then I do not plan to do anything.

- But, I planned to come to tonight’s debate. That is why I am here. From which it follows:

- Therefore, naturalism is not true.

- Seventh is the argument from enduring:

- According to Dr. Rosenberg, if naturalism is true then I do not endure for two moments of time.

- But, I have been sitting here for more than a minute. If you think that you are the same person who walked into the room tonight then you should agree that:

- Therefore, naturalism is not true.

- Finally, the argument from personal existence - this is perhaps the coup de grace against naturalism:

- According to Dr. Rosenberg, if naturalism is true then I do not exist. He says there are no selves, there are no persons, no first-person perspectives.

- But, I do exist! I know this as certainly as I know anything. From which it follows:

- Therefore, naturalism is not true.

- In a word, metaphysical naturalism is absurd. Notice that my argument is not that it is unappealing. Rather, it is that metaphysical naturalism flies in the face of reason and experience and is therefore untenable.

Craig v Dr. Alex Rosenberg Debate Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, February 2013

D

edit- It is impossible to answer your question briefly; and I am not sure that I could do so, even if I wrote at some length. But I may say that the impossibility of conceiving that this grand and wondrous universe, with our conscious selves, arose through chance, seems to me the chief argument for the existence of God; but whether this is an argument of real value, I have never been able to decide. I am aware that if we admit a first cause, the mind still craves to know whence it came, and how it arose. Nor can I overlook the difficulty from the immense amount of suffering through the world. I am, also, induced to defer to a certain extent to the judgment of the many able men who have fully believed in God; but here again I see how poor an argument this is. The safest conclusion seems to me that the whole subject is beyond the scope of man's intellect; but man can do his duty.

- Francis Darwin, son of Charles Darwin, The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin (1887) Edited by his son Francis Darwin, including an abridged version of the Autobiography.,

volume I, chapter VIII: "Religion", pages 306-307; letter to Dutch student N.D. Doedes (2 April 1873)

- It is often said, mainly by the 'no-contests', that although there is no positive evidence for the existence of God, nor is there evidence against his existence. So it is best to keep an open mind and be agnostic. At first sight that seems an unassailable position, at least in the weak sense of Pascal's wager. But on second thoughts it seems a cop-out, because the same could be said of Father Christmas and tooth fairies. There may be fairies at the bottom of the garden. There is no evidence for it, but you can't prove that there aren't any, so shouldn't we be agnostic with respect to fairies?

- From speech oof Richard Dawkins at the Edinburgh International Science Festival, 1992-04-15. Frequently misattributed to The God Delusion.

- quoted in "EDITORIAL: A scientist's case against God". The Independent (London): p. 17. 20 April 1992. and Paul Gomberg (27 May 2011). What Should I Believe?: Philosophical Essays for Critical Thinking. Broadview Press. p. 146. ISBN 9781554810130.

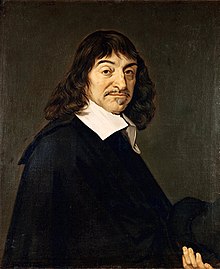

- Because I cannot conceive God unless as existing, it follows that existence is inseparable from him, and therefore that he really exists... the necessity of the existence of God, determines me to think in this way: for it is not in my power to conceive a God without existence, that is a being supremely perfect, and yet devoid of an absolute perfection, as I am free to imagine a horse with or without wings.

- In the course of time one does not feel even the existence of God. After attaining enlightenment one sees that gods and deities are all Maya.

- Sarada Devi, Swami Tapasyananda, Swami Nikhilananda. Sri Sarada Devi, the Holy Mother; Life and Conversations. p. 297.

- For positivism, which has assumed the judicial office of enlightened reason, to speculate about intelligible worlds is no longer merely forbidden but senseless prattle. Positivism—fortunately for it—does not need to be atheistic, since objectified thought cannot even pose the question of the existence of God. The positivist censor turns a blind eye to official worship, as a special, knowledge-free zone of social activity, just as willingly as to art—but never to denial, even when it has a claim to be knowledge. For the scientific temper, any deviation of thought from the business of manipulating the actual, any stepping outside the jurisdiction of existence, is no less senseless and self-destructive than it would be for the magician to step outside the magic circle drawn for his incantation; and in both cases violation of the taboo carries a heavy price for the offender.

- Dialectic of the Enlightenment, E. Jephcott, trans., p. 19

- For positivism, which has assumed the judicial office of enlightened reason, to speculate about intelligible worlds is no longer merely forbidden but senseless prattle. Positivism—fortunately for it—does not need to be atheistic, since objectified thought cannot even pose the question of the existence of God. The positivist censor turns a blind eye to official worship, as a special, knowledge-free zone of social activity, just as willingly as to art—but never to denial, even when it has a claim to be knowledge. For the scientific temper, any deviation of thought from the business of manipulating the actual, any stepping outside the jurisdiction of existence, is no less senseless and self-destructive than it would be for the magician to step outside the magic circle drawn for his incantation; and in both cases violation of the taboo carries a heavy price for the offender.

- According to Descartes, scientists should stay at home and deduce the laws of Nature by pure thought... scientists will need only the rules of logic and knowledge of the existence of God. For four hundred years since Bacon and Descartes... science has raced ahead by following both paths simultaneously. Neither Baconian empiricism nor Cartesian dogmatism has the power to elucidate Nature's secrets by itself, but both together have been amazingly successful. For four hundred years English scientists have tended to be Baconian and French scientists Cartesian. Faraday and Darwin and Rutherford were Baconians; Pascal and Laplace and Poincaré were Cartesians. Newton was at heart a Cartesian, using pure thought... to demolish the Cartesian dogma of vortices. Marie Curie was at heart a Baconian, boiling tons of crude uranium ore to demolish the dogma of the indestructibility of atoms.

- Freeman Dyson, "Birds and Frogs" (Oct. 4, 2008) AMS Einstein Public Lecture in Mathematics, as published in Notices of the AMS, (Feb, 2009). Also published in The Best Writing on Mathematics: 2010 (2011) p. 58.

E

edit- The fantastic 12-digit agreement between the theoretical predictions of QED and the experimental results is a miracle. It would be good for physicists to acknowledge the unsatisfactory mathematical structure of this prediction. It starts from a mathematically undefined Feynman Integral, proceeds by making many very complicated manipulations, and ends up with a formal series that Dyson showed to be divergent! Physicists think of it as an asymptotic expansion, but they have no mathematical proof of this. I often joke that this agreement of theory and experiment is a new proof of the existence of God and that she loves physicists!

- David A. Edwards on the No miracles argument, "Einstein's Dream" (2013)

F

edit- "Ben Stein has a new movie out... called Expelled. It is powerful. It is fabulous." "His interviews with some of the professors who espouse Darwinism are literally shocking. [Despite the] condescension and the arrogance these people have, they will readily admit that Darwinism and evolution do not explain how life began." "These people are so threatened by the existence of God, they will not permit intelligent design to be discussed. Professors have been fired, blackballed, and prevented from working who have deigned to try to combine the whole concept of evolution with intelligent design." "[T]he point of it is that these people on the left are just scared to death of God. It threatens everything. We, on the other hand, recognize that our greatness, who we are, our potential, our ambition, our desire, comes from God"

- Rush Limbaugh, "Ben Stein's Film Blew Rush Away," The Rush Limbaugh Show, March 18, 2008 [2]

- God, I have said, is the fulfiller, or the reality, of the human desires for happiness, perfection, and immortality. From this it may be inferred that to deprive man of God is to tear the heart out of his breast. But I contest the premises from which religion and theology deduce the necessity and existence of God, or of immortality, which is the same thing. I maintain that desires which are fulfilled only in the imagination, or from which the existence of an imaginary being is deduced, are imaginary desires, and not the real desires of the human heart; I maintain that the limitations which the religious imagination annuls in the idea of God or immortality, are necessary determinations of the human essence, which cannot be dissociated from it, and therefore no limitations at all, except precisely in man’s imagination.

- Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach, Lectures on the Essence of Religion (1851), Lecture XXX, Atheism alone a Positive View

G

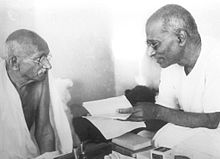

edit- It is beyond my power to induce in you a belief in God. There are certain things which are self proved and certain which are not proved at all. The existence of God is like a geometrical axiom. It may be beyond our heart grasp. I shall not talk of an intellectual grasp. Intellectual attempts are more or less failures, as a rational explanation cannot give you the faith in a living God. For it is a thing beyond the grasp of reason. It transcends reason. There are numerous phenomena from which you can reason out the existence of God, but I shall not insult your intelligence by offering you a rational explanation of that type. I would have you brush aside all rational explanations and begin with a simple childlike faith in God. If I exist, God exists. With me it is a necessity of my being as it is with millions. They may not be able to talk about it, but from their life you can see that it is a part of their life. I am only asking you to restore the belief that has been undermined. In order to do so, you have to unlearn a lot of literature that dazzles your intelligence and throws you off your feet. Start with the faith which is also a token of humility and an admission that we know nothing, that we are less than atoms in this universe. We are less than atoms, I say, because the atom obeys the law of its being, whereas we in the insolence of our ignorance deny the law of nature. But I have no argument to address to those who have no faith.

- Mahatma Ghandi, Young India (24 September 1931); also in Teachings Of Mahatma Gandhi (1945), edited by Jag Parvesh Chander, p. 458 archive.org

- The progenitor of information theory, and perhaps the pivotal figure in the recent history of human thought, was Kurt Gödel, the eccentric Austriac genius and intimate of Einstein who drove determinism from its strongest and most indispensable redoubt; the coherence, consistency, and self-sufficiency of mathematics.

Gödel demonstrated that every logical scheme, including mathematics, is dependent upon axioms that it cannot prove and that cannot be reduced to the scheme itself. In an elegant mathematical proof, introduced to the world by the great mathematician and computer scientist John von Neumann in September 1930, Gödel demonstrated that mathematics was intrinsically incomplete. Gödel was reportedly concerned that he might have inadvertently proved the existence of God, a faux pas in his Viennese and Princeton circle. It was one of the famously paranoid Gödel's more reasonable fears.

- George Gilder, in Knowledge and Power : The Information Theory of Capitalism and How it is Revolutionizing our World (2013), Ch. 10: Romer's Recipes and Their Limits

- Academic scientists of any sort expect to be struck by lightning if they celebrate real creation de novo in the world. One does not expect modern scientists to address creation by God. They have a right to their professional figments such as infinite multiple parallel universes. But it is a strange testimony to our academic life that they also feel it necessary of entrepreneurship to chemistry and cuisine, Romer finally succumbs to the materialist supersition: the idea that human beings and their ideas are ultimately material. Out of the scientistic fog there emerged in the middle of the last century the countervailling ideas if information theory and computer science. The progenitor of information theory, and perhaps the pivotal figure in the recent history of human thought, was Kurt Gödel, the eccentric Austrian genius and intimate of Einstein who drove determinism from its strongest and most indispensable redoubt; the coherence, consistency, and self-sufficiency of mathematics.

Gödel demonstrated that every logical scheme, including mathematics, is dependent upon axioms that it cannot prove and that cannot be reduced to the scheme itself. In an elegant mathematical proof, introduced to the world by the great mathematician and computer scientist John von Neumann in September 1930, Gödel demonstrated that mathematics was intrinsically incomplete. Gödel was reportedly concerned that he might have inadvertently proved the existence of God, a faux pas in his Viennese and Princeton circle. It was one of the famously paranoid Gödel's more reasonable fears. As the economist Steven Landsberg, an academic atheist, put it, "Mathematics is the only faith-based science that can prove it."- George Gilder, Knowledge and Power : The Information Theory of Capitalism and How it is Revolutionizing our World (2013), Ch. 10: Romer's Recipes and Their Limits

The current worldview has it that everything is made of matter, and everything can be reduced to the elementary particles of matter, the basic constituents — building blocks — of matter.' And cause arises from the interactions of these basic building blocks or elementary particles; elementary particles make atoms, atoms make molecules, molecules make cells, and cells make brain. But all the way, the ultimate cause is always the interactions between the elementary particles. This is the belief — all cause moves from the elementary particles. This is what we call "upward causation." So in this view, what human beings — you and I think of as our free will does not really exist. It is only an epiphenomenon or secondary phenomenon, secondary to the causal power of matter. And any causal power that we seem to be able to exert on matter is just an illusion. This is the current paradigm.

Now, the opposite view is that everything starts with consciousness. That is, consciousness is the ground of all being. In this view, consciousness imposes "downward causation." In other words, our free will is real. When we act in the world we really are acting with causal power. This view does not deny that matter also has causal potency — it does not deny that there is causal power from elementary particles upward, so there is upward causation — but in addition it insists that there is also downward causation. It shows up in our creativity and acts of free will, or when we make moral decisions. In those occasions we are actually witnessing downward causation by consciousness.

- He [Spinoza] does not prove the existence of God, existence is God. And if for this reason others would brand him Atheum then I would praise him and call him theissimum and christianissimum. [Original in German: Du erkennst die höchste Realität an, welche der Grund des ganzen Spinozismus ist, worauf alles übrige ruht, woraus alles übrigefliest. Er [Spinoza] beweist nicht das Daseyn Gottes, das Daseyn ist Gott. Und wenn ihn andre deshalb Atheum schelten, so mögte ich ihn theissimum ja christianissimum nennen und preisen.]

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, in one of his letters to Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi, 1785[specific citation needed]

H

edit- In the religion of absolute Spirit the outward form of God is not made by the human spirit. God Himself is, in accordance with the true Idea, self-consciousness which exists in and for itself, Spirit. He produces Himself of His own act, appears as Being for “Other”; He is, by His own act, the Son; in the assumption of a definite form as the Son, the other part of the process is present, namely, that God loves the Son, posits Himself as identical with Him, yet also as distinct from Him. The assumption of form makes its appearance in the aspect of determinate Being as independent totality, but as a totality which is retained within love; here, for the first time, we have Spirit in and for itself. The self-consciousness of the Son regarding Himself is at the same time His knowledge of the Father; in the Father the Son has knowledge of His own self, of Himself. At our present stage, on the contrary, the determinate existence of God as God is not existence posited by Himself, but by what is Other. Here Spirit has stopped short half way.

- Hegel, Lectures on the philosophy of religion, together with a work on the proofs of the existence of God. Vol 3 Translated from the 2d German ed. 1895 Ebenezer Brown Speirs 1854-1900, and J Burdon Sanderson P. 3.

- Here I am with my Spinoza, but almost more in the dark than I was before. It is plain on every page that he is no atheist. For him the idea of God is the first and last, yes, I might even say the only idea of all, for on it he bases knowledge of the world and of nature, consciousness of self and of all things around him, his ethics and his politics. Without the idea of God, his mind has no power, not even to conceive of itself. For him it is well nigh inconceivable, how men can, as it were, turn God into a mere consequence of other truths, or even of sensuous perceptions, since all truth, like all existence, follows only from eternal truth, from the eternal, infinite existence of God. This conception became so present, so immediate and intimate to him, that I certainly would rather have taken him to be an enthusiast concerning the existence of God, than a doubter or denier of it. He places all mankind's perfection, virtue and blessedness in the knowledge and love of God. And that this is not some sort of mask which he has assumed, but rather his deepest feeling, is shown by his letters, yes, I might even say, by every part of his philosophical system, by every line of his writings. Spinoza may have erred in a thousand ways about the idea of God, but how readers of his works could ever say that he denied the idea of God and proved atheism, is incomprehensible to me.

- Johann Gottfried Herder, God, Some Conversations (1787) [original in German]

- For positivism, which has assumed the judicial office of enlightened reason, to speculate about intelligible worlds is no longer merely forbidden but senseless prattle. Positivism—fortunately for it—does not need to be atheistic, since objectified thought cannot even pose the question of the existence of God. The positivist censor turns a blind eye to official worship, as a special, knowledge-free zone of social activity, just as willingly as to art—but never to denial, even when it has a claim to be knowledge. For the scientific temper, any deviation of thought from the business of manipulating the actual, any stepping outside the jurisdiction of existence, is no less senseless and self-destructive than it would be for the magician to step outside the magic circle drawn for his incantation; and in both cases violation of the taboo carries a heavy price for the offender.

- Horkheimer and Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment, E. Jephcott, trans., p. 19.

- This age proclaims the sovereignty of the citizen, and the inviolability of life; it crowns the people, and consecrates man. In art, it possesses all varieties of genius,—writers, orators, poets, historians, publicists, philosophers, painters, sculptors, musicians; majesty, grace, power, force, splendour, colour, form, style; it renews its strength in the real and in the ideal, and bears in its hand the two thunderbolts, the true and the beautiful. In science it accomplishes unheard-of miracles; it makes of cotton salt petre, of steam a horse, of the voltaic battery a workman, of the electric fluid a messenger, of the sun a painter; it waters itself with subterranean streams, pending the time when it shall warm itself with the central fire; it opens upon the two infinites those two windows, the telescope upon the infinitely great, the microscope upon the infinitely little, and it finds stars in the first abyss, and insects in the second, which prove to it the existence of God... It annihilates time, it annihilates space, it annihilates suffering; it writes a letter from Paris to London, and has an answer in ten minutes; it cuts off a man's leg, the man sings and smiles. Conclusion, Part Second, II

- Victor Hugo, Napoleon the Little (1852)

- Then one day, I took my courage in both hands. I first expanded my reading and immersed myself in philosophical and scientific works that called for reflection on the existence of God, such as To End God with the British Richard Dawkins. This book brought me the answers that religion was unable to provide me. Through the work of Darwin, Hawking, and other scientists who have marked humanity, I have discovered that most scholars are atheists. I had come to understand why the work of these scholars was not taught in our schools and universities: simply because those of Dawkins or for example, the theory of evolution of Darwin, go against the primacy of religion on science. ... / ... The Internet has allowed me to discover that the famous miracles of Islam, claimed by the religious and willingly relayed by the press and Islamic satellite television, were just lies. ... / ... Darwin's theory of evolution seemed to me much more convincing than the legend of Adam and Eve.

- Waleed Al-Husseini, The Blasphemer: The Price I Paid for Rejecting Islam, Arcade, 2017. ISBN 978-1628726756

I

edit- Theological arguments are supposed to provide ‘explanations’ for the existence of God. That means these arguments ought to persuade and make anyone who does not know about God to at least understand that God exists. But unfortunately, this is not the case. Anyone who takes a critical look at the theological arguments would really wonder what those who advanced these explanations had in mind.

- Leo Igwe, An Interview with Dr. Leo Igwe — Founder, Nigerian Humanist Movement (2017), An Interview with Dr. Leo Igwe — Founder, Nigerian Humanist Movement (June 23, 2017), Medium.

- It was while most anxious to solve these perplexing problems that we came into contact with certain men, endowed with such mysterious powers and such profound knowledge that we may truly designate them as the sages of the Orient. To Their instructions we lent a ready ear. They showed us that by combining science with religion, the existence of God and immortality of man's spirit may be demonstrated like a problem of Euclid. For the first time we received the assurance that the Oriental philosophy has room for no other faith than an absolute and immovable faith in the omnipotence of man's own immortal self. We were taught that this omnipotence comes from the kinship of man's spirit with the Universal Soul — God!

- Isis Unveiled, Vol. I Preface

J

edit- Divine agnosticism, the sort I'm advocating, affirms the existence of God but then acknowledges our human inability to fully grasp his infinite nature.

- Skye Jethani, The Divine Commodity: Discovering A Faith Beyond Consumer Christianity (2009, Zondervan)

- When we talk about proof of the existence of God, we must underline that it is not proof of a scientific-experimental nature. Scientific evidence, in the modern sense of the word, is valid only for things perceptible to the senses, since only on these can the instruments of investigation and verification, which science uses, be exercised. Wanting scientific proof of God would mean lowering God to the rank of beings in our world, and therefore already being methodologically wrong about what God is. Science must recognize its limits and its impotence to reach the existence of God: it can neither affirm nor deny this existence. However, the conclusion must not be drawn from this that scientists are incapable of finding, in their scientific studies, valid reasons to admit the existence of God. If science, as such, cannot reach God, the scientist, who possesses intelligence whose object is not limited to sensible things, can discover in the world the reasons for affirming a being that surpasses it. Many scientists have made and are making this discovery.

- Pope John Paul II. Source: Libreria editrice vaticana (in Italian)

- Professor Behe remarkably and unmistakably claims that the plausibility of the argument for ID [Intelligent Design] depends upon the extent to which one believes in the existence of God. As no evidence in the record indicates that any other scientific proposition's validity rests on belief in God, nor is the Court aware of any such scientific propositions, Professor Behe's assertion constitutes substantial evidence that in his view, as is commensurate with other prominent ID leaders, ID is a religious and not a scientific proposition.

- Judge John E. Jones III, Opinion in Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, 20 December 2005, p. 28.

K

edit- Historically, Ockham has been cast as the outstanding opponent of Thomas Aquinas (1224–1274): Aquinas perfected the great "medieval synthesis" of faith and reason and was canonized by the Catholic Church; Ockham destroyed the synthesis and was condemned by the Catholic Church. Although it is true that Aquinas and Ockham disagreed on most issues, Aquinas had many other critics, and Ockham did not criticize Aquinas any more than he did others. It is fair enough, however, to say that Ockham was a major force of change at the end of the Middle Ages. He was a courageous man with an uncommonly sharp mind. His philosophy was radical in his day and continues to provide insight into current philosophical debates.

The principle of simplicity is the central theme of Ockham's approach, so much so that this principle has come to be known as "Ockham's Razor." Ockham uses the razor to eliminate unnecessary hypotheses. In metaphysics, Ockham champions nominalism, the view that universal essences, such as humanity or whiteness, are nothing more than concepts in the mind. He develops an Aristotelian ontology, admitting only individual substances and qualities. In epistemology, Ockham defends direct realist empiricism, according to which human beings perceive objects through "intuitive cognition," without the help of any innate ideas. These perceptions give rise to all of our abstract concepts and provide knowledge of the world. In logic, Ockham presents a version of supposition theory to support his commitment to mental language. Supposition theory had various purposes in medieval logic, one of which was to explain how words bear meaning. Theologically, Ockham is a fideist, maintaining that belief in God is a matter of faith rather than knowledge. Against the mainstream, he insists that theology is not a science and rejects all the alleged proofs of the existence of God.

- Sharon Kaye, in "William of Ockham" at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- There is no reason why someone who is in doubt about the existence of God should not pray for help and guidance on this topic as in other matters. Some find something comic in the idea of an agnostic praying to a God whose existence he doubts. It is surely no more unreasonable than the act of a man adrift in the ocean, trapped if a cave, or stranded on a mountainside, who cries for help though he may never be heard or fires a signal which may never be seen.

- Anthony Kenny, The God of the Philosophers (1979), p. 129

- “So the temple of Somnath was made to bow towards the Holy Mecca; and as the temple lowered its head and jumped into the sea, you may say that the building first said its prayers and then had a bath… It seemed as if the tongue of the Imperial sword explained the meaning of the text: ‘So he (Abraham) broke them (the idols) into pieces except the chief of them, that haply they may return to it.’ Such a pagan country, the Mecca of the infidels, now became the Medina of Islam. The followers of Abraham now acted as guides in place of the Brahman leaders. The robust-hearted true believers rigorously broke all idols and temples wherever they found them. Owing to the war, ‘takbir,’ and ‘shahadat’ was heard on every side; even the idols by their breaking affirmed the existence of God. In this ancient land of infidelity the call to prayers rose so high that it was heard in Baghdad and Madain (Ctesiphon) while the ‘Ala’ proclamation (Khutba) resounded in the dome of Abraham and over the water of Zamzam… The sword of Islam purified the land as the Sun purifies the earth.”

- Amir Khusrow, about Sultan ‘Alau’d-Din Khalji (AD 1296-1316) and his generals conquests in Somnath (Gujarat) Mohammed Habib's translation quoted by Jagdish Narayan Sarkar, The Art of War in Medieval India, New Delhi, 1964, pp. 286-87.

- Variant: Then they made the idol temple of Somnath bow in reverence towards the holy Ka‘ba and when they threw the spectre of the shamefaced idol temple into the sea, it was as if the idol temple had first said its prayers and then performed its ritual ablutions.’ in Peter Hardy - Historians of medieval India_ studies in Indo-Muslim historical writing. (1960)

- There was a thinker who became a hero by his death; he said that he could demonstrate the existence of God with a single straw.

- The demonstration of the existence of God is something with which one learnedly and metaphysically occupies oneself only on occasion, but the thought of God forces itself upon a man on every occasion. What is it that such an individuality lacks? Inwardness.

- Søren Kierkegaard, Begrebet Angest (The Concept of Anxiety), Anxiety of Sin or Anxiety as the Consequence of Sin in the Single Individual, p. 140

- After having worked in the theory of light and gravitation, he announced, in 1744, a new minimum principle, the Principle of Least Action, from which he claimed he could deduce the behavior of light and masses in motion. The principle asserts that nature always behaves so as to minimize an integral known technically as action, and amounting to the integral of the product of mass, velocity, and distance traversed by a moving object. From this principle he deduced the Newtonian laws of motion. With sometimes suitable and sometimes questionable interpretation of the quantities involved, Maupertuis managed to show that optical phenomena, too, could be deduced from this principle. Hence, to an extent at least, he succeeded in uniting the optics of the eighteenth century and mechanical phenomena. ...

Maupertuis advocated his principle for theological reasons. ...He ...proclaimed his principle to be not only a universal law of nature but also the first scientific proof of the existence of God, for it was "so wise a principle as to be worthy only of a Supreme Being.- Morris Kline, Mathematics and the Physical World (1959) Ch. 25: From Calculus to Cosmic Planning, p. 438.

- 'So the temple of Somnath was made to bow towards the Holy Mecca; and as the temple lowered its head and jumped into the sea, you may say that the building first said its prayers and then had a bath' It seemed as if the tongue of the Imperial sword explained the meaning of the text: 'So he (Abraham) broke them (the idols) into pieces except the chief of them, that haply they may return to it.' Such a pagan country, the Mecca of the infidels, now became the Medina of Islam. The followers of Abraham now acted as guides in place of the Brahman leaders. The robust-hearted true believers rigorously broke all idols and temples wherever they found them. Owing to the war, 'takbir,' and 'shahadat' was heard on every side; even the idols by their breaking affirmed the existence of God. In this ancient land of infidelity the call to prayers rose so high that it was heard in Baghdad and Madain (Ctesiphon) while the 'Ala' proclamation (Khutba) resounded in the dome of Abraham and over the water of Zamzam' The sword of Islam purified the land as the Sun purifies the earth.'

- Khazainul-Futuh by Amir Khusru, translated by Mohammed Habib, Quoted by Jagdish Narayan Sarkar, The Art of War in Medieval India, New Delhi, 1964, pp. 286-87.

L

edit- Denying the existence of God the Creator is like an artificial intelligent machine doubting the existence of human inventors.

- Newton Lee, Google It: Total Information Awareness, 2016

- There have been men before ... who got so interested in proving the existence of God that they came to care nothing for God himself... as if the good Lord had nothing to do but to exist. There have been some who were so preoccupied with spreading Christianity that they never gave a thought to Christ.

- C. S. Lewis, Perelandra, Ch. 9

- The most surprising and original part of [Lucien Goldmann's] work is, however, the attempt to compare—without assimilating one to another—religious faith and Marxist faith: both have in common the refusal of pure individualism (rationalist or empiricist) and the belief in trans-individual values—God for religion, the human community for socialism. In both cases the faith is based on a wager—the Pascalian wager on the existence of God and the Marxist wager on the liberation of humanity—that presupposes risk, the danger of failure and the hope of success.

- Michael Löwy, The War of Gods: Religion and Politics in Latin America (1996), p. 17

- We must remember that it's possible to affirm the existence of God with your lips and deny his existence with your life. The most dangerous type of atheism is not theoretical atheism, but practical atheism ... that's the most dangerous type. And the world, even the church, is filled up with people who pay lip service to God and not life service. And there is always a danger that we will make it appear externally that we believe in God when internally we don't. We say with our mouths that we believe in him, but we live with our lives like he never existed. That is the ever-present danger confronting religion. That's a dangerous type of atheism.

M

edit- You are no doubt aware that the Almighty, desiring to lead us to perfection and to improve our state of society, has revealed to us laws which are to regulate our actions. These laws, however, presuppose an advanced state of intellectual culture. We must first form a conception of the Existence of the Creator according to our capabilities; that is, we must have a knowledge of Metaphysics. But this discipline can only be approached after the study of Physics: for the science of Physics borders on Metaphysics, and must even precede it in the course of our studies, as is clear to all who are familiar with these questions.

- Maimonides, Guide for the Perplexed (c. 1190), Introduction

- The being which has absolute existence, which has never been and will never be without existence, is not in need of an agent...The question, "What is the purpose thereof?" cannot be asked about anything which is not the product of an agent; therefore we cannot ask what is the purpose of the existence of God...For that which is without a beginning, a final cause need not be sought...This must be our belief when we have a correct knowledge of our own self, and comprehend the true nature of everything; we must be content, and not trouble our mind with seeking a certain final cause for things that have none, or have no other final cause but their own existence, which depends on the Will of God, or, if you prefer, on the Divine Wisdom...If the whole earth is infinitely small in comparison with the sphere of the stars, what is man compared with all these created beings? How, then, could any one of us imagine that these things exist for his sake and benefit, and that they are his tools! This is a result of an examination of the corporeal beings: how much more so will be the result of an examination of the Intelligences!

- Maimonides, Guide for the Perplexed (c. 1190), Ch. 13

- A necessity of my reason constrains me to believe the existence of God, because I can in no other way account for my own existence.… I know that I am. I am either uncaused, or self-caused, or caused by a cause.

- Henry Edward Manning, Religio Viatoris (London: Burns and Oates, 1887), p. 1.

- I departed from parental paths significantly and abruptly one Sunday morning when, sitting in the family pew of the Hyde Park United Church and idly twisting a loose button on the cushion beside me, I said to myself, "I do not believe in God." Some months previously... when our minister fell back on St. Anselm's ontological argument to prove the existence of God, he entirely failed to convince me. Quite the contrary, the argument struck me as an abuse of language. Though I duly submitted to the ritual of confirmation... Horton's unconvincing argument had sown doubt in my mind; and for that reason I can assign, on that morning, listening to his more emotional, hortatory rhetoric... the balance tipped, committing me to a secret, personal rejection of the Christian piety my parents held dear.

- William H. McNeill, The Pursuit of Truth: A Historian's Memoir (2005)

- God, if he exists, is hidden.

If he exists, men have always been forced to grope for him. And their research does not always have an outcome or a result. Whether positive or negative. One should wonder and be wary of those who claim they have no difficulty believing. Perhaps (as has been said) it is because they have not quite understood what it is about.

The despairing human experience is that no divinity peeks out from behind the clouds. Heaven and earth are silent.

But, if a god exists, he is not only hidden behind the silence of nature. He also hides behind the reality of the evil of the innocent which seems to accuse him without the possibility of defence; behind the multiplicity of religions. In these, behind the difficulties of the many "sacred writings", including the Bible.

If it exists, it is also hidden behind the scandals of the churches; behind the errors and inconsistencies of those precisely who should testify to their existence with life itself. (I understood)- Vittorio Messori, Hypotheses about Jesus, Ch, I

N

edit- YHWH commanded us to abstain from work on the Sabbath, and to rest, for two purposes; namely, (1) That we might confirm the true theory, that of the Creation, which at once and clearly leads to the theory of the existence of God. (2) That we might remember how kind God had been in freeing us from the burden of the Egyptians - The Sabbath is therefore a double blessing: it gives us correct notions, and also promotes the well-being of our bodies.

- Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman (Ramban), "ארכיון הדף היומי". vbm-torah.org

- The existence of God is attested by everything that appeals to our imagination. And if our eye cannot reach Him it is because He has not permitted our intelligence to go so far.

- Napoleon : In His Own Words (1916) edited by Jules Bertaut, as translated by Herbert Edward Law and Charles Lincoln Rhodes

- In default of any other proof, the thumb would convince me of the existence of a God.

- Attributed to Isaac Newton as "A défaut d'autres preuves, le pouce me convaincrait de l'existence de Dieu" in a treatise on palmistry: d'Arpentigny, Stanislas (1856). "IV: Le pouce" (in French). La science de la main (2nd ed.). Paris, France: Coulon-Pineau. p. 53. A later translation by Edward Heron-Allen renders the phrase as "In default of any other proofs, the thumb would convince me of the existence of God", and acknowledges that it does not seem to appear in any of Newton's works [d'Arpentigny, Casimir Stanislas (1889). "Sub-Section IV: The Thumb" (in English). The Science of the Hand. London, England: Ward, Lock and Co.. p. 138.]

- Reported as something said by Newton in a section on palmistry in Charles Dickens's All the Year Round (1864), Vol. 10, p. 346; later found in "The Book of the Hand" (1867) by A R. Craig, S. Low and Marston, p. 51:

- "In want of other proofs, the thumb would convince me of the existence of a God; as without the thumb the hand would be a defective and incomplete instrument, so without the moral will, logic, decision, faculties of which the thumb in different degrees offers the different signs, the most fertile and the most brilliant mind would only be a gift without worth. [No closing quotations marks exist to specify the end of the quotation and the beginning of the author's commentary.]

- A slight variant of this is cited as something Newton once "exclaimed" in Human Nature : An Interdisciplinary Biosocial Perspective, Vol. 1, Issues 7-12 (1978), p. 47: "In the absence of any other proof, the thumb alone would convince me of God's existence."

- "In want of other proofs, the thumb would convince me of the existence of a God; as without the thumb the hand would be a defective and incomplete instrument, so without the moral will, logic, decision, faculties of which the thumb in different degrees offers the different signs, the most fertile and the most brilliant mind would only be a gift without worth. [No closing quotations marks exist to specify the end of the quotation and the beginning of the author's commentary.]

P

edit- Giving then to matter all the properties which philosophy knows it has, or all that atheism ascribes to it, and can prove, and even supposing matter to be eternal, it will not account for the system of the universe or of the solar system, because it will not account for motion, and it is motion that preserves it. When, therefore, we discover a circumstance of such immense importance, that without it the universe could not exist, and for which neither matter, nor any, nor all, the properties of matter can account, we are by necessity forced into the rational and comfortable belief of the existence of a cause superior to matter, and that cause man calls, God.

- Thomas Paine, "A Discourse delivered by Thomas Paine, at the Society of the Theophilanthropists at Paris, 1798", reviewed in The Monthly Review, or, Literary Journal, Vol. 30, pp. 113-4, by Ralph Griffiths, G. E. Griffiths (1799); republished in Miscellaneous Letters and Essays, on Various Subjects (1817), pp. 62–72

- The existence of God cannot be used as any scientific hypothesis: it is something different that transcends science. [...] I would be a terrible theologian if I tried to do an experiment to prove the existence of God, and a terrible scientist if I tried to explain my experimental data by hypothesizing the existence of God. [...] I'm always annoyed when people ask me about my religious opinions in interviews. I don't think they ever ask that of footballers, singers, models, categories for which I have the utmost respect. Interviewers implicitly assume that scientists possess privileged knowledge of God, but this is not true.

- Letter of Giorgio Parisi to Avvenire, commented by Marco Tarquinio, Giorgio Parisi: the extreme syntheses betray and the «God hypothesis» transcends science (October 12, 2021)

- Lichtenberg … held something of the following kind: one should neither affirm the existence of God nor deny it. … It is not that he wished to leave certain perspectives open, nor to please everyone. It is rather that he was identifying himself, for his part, with a consciousness of self, of the world, and of others that was “strange” (the word is his) in a sense which is equally well destroyed by the rival explanations.

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty, In Praise of Philosophy (1963), pp. 45-46

- The gross materialists do not believe in the existence of God or the demigods. Nor do they believe that different planets are dominated by different demigods. They are creating a great commotion about reaching the closest celestial body, Candraloka, or the Moon, but even after much mechanical research they have only very scanty information of this Moon, and in spite of much false advertisement for selling land on the Moon, the puffed-up scientists or gross materialists cannot live there, and what to speak of reaching the other planets, which they are unable even to count.

- A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, Srimad Bhagavatam, Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1999. Canto 2, Chapter 3, verse 11, purport. Vedabase

- When we say there is a GOD, we mean that there is an intelligent designing cause of what we see in the world around us, and a being who was himself uncaused.

- Joseph Priestley, Institutes of Natural and Revealed Religion (1772–1774). Vol. I : Part I : The Being and Attributes of God, § 1 : Of the existence of God, and those attributes which art deduced from his being considered as uncaused himself, and the cause of every thing else (1772)

R

edit- Proving evolution wouldn’t disprove God unless your god is a book. The Bible is easy to disprove, but that shouldn’t be enough to disprove God. Whether God exists or not, evolution is still an inescapable fact of population genetics and the Bible is still a man-made compilation of falsified fables. Not even the existence of God could change either of these things.

- Aron Ra, Correspondence with a Creationist (June 6, 2017)

- The tradition in Hinduism is that it is not open to any Hindu, whatever be the name and mental image of the Supreme Being he uses for his devotional exercises, to deny the existence of God that others worship. He can raise the name of his choice to that of the highest, but he can not deny the divinity or the truth of the God of other denominations. The fervor of his own piety just gives predominance to the name and form he gives for his own worship and contemplation, and he treats the other gods as deriving the divinity therefrom. This reduces all controversy to a devotional technique of concentration on a peculiar name and mental form or concrete symbol as representing the supreme being. It makes no difference in the contents of Vedanta to which all devotees equally subscribe… ‘just as all water raining from the skies goes to the ocean, worship of all gods go to Keshava.’

- C. Rajagopalachari (1900) Hinduism, doctrine and way of life, p. 31; As quoted in Rao, K.L. Seshagiri (1 January 1990). Mahatma Gandhi And Comparative Religion. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.. pp. 110–.

- The influence of Meister Eckhart is stronger today than it has been in hundreds of years. Eckhart met the problems of contingency and omnipotence, creator-and-creature-from-nothing by making God the only reality and the presence or imprint of God upon nothing, the source of reality in the creature. Reality in other words was a hierarchically structured participation of the creature in the creator. From the point of view of the creature this process could be reversed. If creatureliness is real, God becomes the Divine Nothing. God is not, as in scholasticism, the final subject of all predicates. He is being as unpredicable. The existence of the creature, in so far as it exists, is the existence of God, and the creature's experience of God is therefore in the final analysis equally unpredicable. Neither can even be described; both can only be indicated. We can only point at reality, our own or God's. The soul comes to the realization of God by knowledge, not as in the older Christian mysticism by love. Love is the garment of knowledge. The soul first trains itself by systematic unknowing until at last it confronts the only reality, the only knowledge, God manifest in itself. The soul can say nothing about this experience in the sense of defining it. It can only reveal it to others.

- Kenneth Rexroth, in "Eckhart, Brethren of the Free Spirit," from Communalism: From Its Origins to the Twentieth Century (1974), ch. 4

- The ultimate source of our civilization's disease is the spiritual and religious crisis which has overtaken all of us and which each must master for himself. Above all, man is Homo religiosus, and yet we have, for the past century, made the desperate attempt to get along without God, and in the place of God we have set up the cult of man, his profane or even ungodly science and art, his technical achievements, and his State. We may be certain that some day the whole world will come to see, in a blinding flash, what is now clear to only a few, namely, that this desperate attempt has created a situation in which man can have no spiritual and moral life, and this means that he cannot live at all for any length of time, in spite of television and speedways and holiday trips and comfortable apartments. We seem to have proved the existence of God in yet another way: by the practical consequences of His assumed non-existence.

- Wilhelm Röpke, A Humane Economy: The Social Framework of the Free Market (1958)

- What we know of physical and biological science makes existence of God less probable than the existence of Santa Claus. And the parts of physics that rule out God are not themselves open to much doubt. There is no chance that they will be revised by anything yet to be discovered. To be sure, there will be revolutionary developments in science. Superstring theory may give way to quantum-loop gravity; exceptions to the genetic code may be discovered; some unique function of consciousness may be identified. But there are some things that won't happen. Purposes and designs will never have a role in physics and biology. Perpetual motion machines and other violations of the laws of thermodynamics won't arise, not even if there turns out to be such a thing as cold fusion.

- Alexander Rosenberg, The Atheist's Guide to Reality (2011)

- If we count the galaxies of the world or we show existence of elementary particles, in an analogous way we probably cannot have evidence for God. But, as a research scientist, I am deeply impressed by the order and the beauty that I find in the cosmos, as well as inside the material things. And as an observer of nature, I cannot help thinking that a greater order exists. The idea that all this is the result of randomness or purely statistical diversity is for me completely unacceptable. There is an Intelligence at a higher level, beyond the existence of the universe itself.

- Nobel Prize Carlo Rubbia, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, märz 1993. As quoted in If science exists, this means that there's a Logic, fame physicist said (April 4, 2017)

- I should say that the universe is just there, and that is all. A physicist looks for causes; that does not necessarily imply that there are causes everywhere. A man may look for gold without assuming that there is gold everywhere; if he finds gold, well and good, if he doesn't he's had bad luck. The same is true when the physicists look for causes. The fact that a belief has a good moral effect upon a man is no evidence whatsoever in favor of its truth.

- BBC Radio Debate on the Existence of God, Bertrand Russell v. Frederick Copleston (1948)

- [T]here used to be in the old days three intellectual arguments for the existence of God, all of which were disposed of by Immanuel Kant in the Critique of Pure Reason; but no sooner had he disposed of those arguments than he invented a new one, a moral argument, and that quite convinced him. He was like many people: in intellectual matters he was skeptical, but in moral matters he believed implicitly in the maxims that he had imbibed at his mother's knee. That illustrates what the psychoanalysts so much emphasize — the immensely stronger hold upon us that our very early associations have than those of later times.

- Bertrand Russell, Why I Am Not a Christian (1927)

- Ever since Plato most philosophers have considered it part of their business to produce ‘proofs’ of immortality and the existence of God. They have found fault with the proofs of their predecessors — Saint Thomas rejected Saint Anselm's proofs, and Kant rejected Descartes' — but they have supplied new ones of their own. In order to make their proofs seem valid, they have had to falsify logic, to make mathematics mystical, and to pretend that deep seated prejudices were heaven-sent intuitions.

- Bertrand Russell, Ie – Evaluating “Proofs” of God’s Existence, Zenofzero.net, 30 October 2012.

- George Berkeley … is important in philosophy through his denial of the existence of matter—a denial which he supported by a number of ingenious arguments. He maintained that material objects only exist through being perceived. To the objection that, in that case, a tree, for instance, would cease to exist if no one was looking at it, he replied that God always perceives everything; if there were no God, what we take to be material objects would have a jerky life, suddenly leaping into being when we look at them; but as it is, owing to God’s perceptions, trees and rocks and stones have an existence as continuous as common sense supposes. This is, in his opinion, a weighty argument for the existence of God.

- Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy (1945), III, I., Ch. XVI: "Berkeley", p. 647

S

edit- Those who raise questions about the God hypothesis and the soul hypothesis are by no means all atheists. An atheist is someone who is certain that God does not exist, someone who has compelling evidence against the existence of God. I know of no such compelling evidence. Because God can be relegated to remote times and places and to ultimate causes, we would have to know a great deal more about the universe than we do to be sure that no such God exists. To be certain of the existence of God and to be certain of the nonexistence of God seem to me to be the confident extremes in a subject so riddled with doubt and uncertainty as to inspire very little confidence indeed.

- Conversations with Carl Sagan (2006), edited by Tom Head, p. 70

- Existentialism is nothing else but an attempt to draw the full conclusions from a consistently atheistic position. Its intention is not in the least that of plunging men into despair. And if by despair one means as the Christians do – any attitude of unbelief, the despair of the existentialists is something different. Existentialism is not atheist in the sense that it would exhaust itself in demonstrations of the non-existence of God. It declares, rather, that even if God existed that would make no difference from its point of view. Not that we believe God does exist, but we think that the real problem is not that of His existence; what man needs is to find himself again and to understand that nothing can save him from himself, not even a valid proof of the existence of God. In this sense existentialism is optimistic. It is a doctrine of action, and it is only by self-deception, by confining their own despair with ours that Christians can describe us as without hope.

- Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism Is a Humanism, lecture (1946)

- I've watched closely and I believe most people who turn from God do so for one of two basic reasons. One, they mistake some aspect of religion as God (like Anton LaVey did). Or two, they are unable to overcome their need to understand what can not be understood. I honestly don't think it's easy to turn from God if we see Him as He really is. Every Satanist I've ever encountered has fallen into one of those two categories. They either have a warped, distorted perception of God, based on what they were taught by some idiot, or they don’t believe in the goodness or even the existence of God because of the injustice of the world. The first is a problem of perception. The second is a problem of pride. Both are hard to get past.

- Sean Sellers, Open Letter To Satanists (Full text online)

- That anything should exist at all does seem to me a matter for the deepest awe. But whether other people feel this sort of awe, and whether they or I ought to is another question. I think we ought to.

- J. J. C. Smart, The Existence of God, Church Quarterly Review, 156(319): 194 (1955).

- Whoever believes in a God at all, believes in an infinite mystery; and if the existence of God is such an infinite mystery, we can very well expect and afford to have many of His ways mysterious to us.

- Ichabod Spencer, 'Dictionary of Burning Words of Brilliant Writers (1895), P. 421.