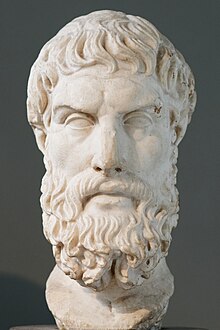

Epicurus

ancient Greek philosopher

Epicurus (341 BC – 270 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosopher and Sage whose ideas gave rise to systems of thought known as Epicureanism. Influenced by Democritus, Aristippus, Pyrrho, and possibly the Cynics, he turned against the Platonism of his day. He openly allowed women and slaves to join the school as a matter of policy.

Quotes

editWhat is terrible is easy to endure.

- Μη φοβάσαι τον θεό,

Μην ανησυχείτε για το θάνατο.

Αυτό που είναι καλό είναι εύκολο να αποκτηθεί, και

Αυτό που είναι τρομερό είναι εύκολο να υπομείνει.- Don't fear god,

Don't worry about death;

What is good is easy to get, and

What is terrible is easy to endure.- The "Tetrapharmakos" [τετραφάρμακος], or "The four-part cure" of Epicurus, from the "Herculaneum Papyrus", 1005, 4.9–14 of Philodemus, as translated in The Epicurus Reader: Selected Writings and Testimonia (1994) edited by D. S. Hutchinson, p. vi

- Don't fear god,

- Δικαιοσύνης καρπὸς μέγιστος ἀταραξία.

- The greatest reward of righteousness is peace of mind.

- Attributed to Epicurus by Clement of Alexandria in Stromata

- The greatest reward of righteousness is peace of mind.

- Luxurious food and drinks, in no way protect you from harm. Wealth beyond what is natural, is no more use than an overflowing container. Real value is not generated by theaters, and baths, perfumes or ointments, but by philosophy.

- From the esplanade wall at Oenoanda, now in Turkey, as recorded by Diogenes of Oenoanda

- Let no one be slow to seek wisdom when he is young nor weary in the search of it when he has grown old. For no age is too early or too late for the health of the soul. And to say that the season for studying philosophy has not yet come, or that it is past and gone, is like saying that the season for happiness is not yet or that it is now no more. Therefore, both old and young alike ought to seek wisdom, the former in order that, as age comes over him, he may be young in good things because of the grace of what has been, and the latter in order that, while he is young, he may at the same time be old, because he has no fear of the things which are to come. So we must exercise ourselves in the things which bring happiness, since, if that be present, we have everything, and, if that be absent, all our actions are directed towards attaining it.

- "Letter to Menoeceus", as translated in Stoic and Epicurean (1910) by Robert Drew Hicks, p. 167

- Variant translation: Let no one delay to study philosophy while he is young, and when he is old let him not become weary of the study; for no man can ever find the time unsuitable or too late to study the health of his soul. And he who asserts either that it is not yet time to philosophize, or that the hour is passed, is like a man who should say that the time is not yet come to be happy, or that it is too late. So that both young and old should study philosophy, the one in order that, when he is old, he many be young in good things through the pleasing recollection of the past, and the other in order that he may be at the same time both young and old, in consequence of his absence of fear for the future.

- τὸ φρικωδέστατον οὖν τῶν κακῶν ὁ θάνατος οὐθὲν πρὸς ἡμᾶς͵ ἐπειδήπερ ὅταν μὲν ἡμεῖς ὦμεν͵ ὁ θάνατος οὐ πάρεστιν͵ ὅταν δὲ ὁ θάνατος παρῇ͵ τόθ΄ ἡμεῖς οὐκ ἐσμέν.

- Death, therefore, the most awful of evils, is nothing to us, seeing that, when we are, death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not.

- "Letter to Menoeceus", as translated in Stoic and Epicurean (1910) by Robert Drew Hicks, p. 169

- He who is not satisfied with a little, is satisfied with nothing.

- The Essential Epicurus : Letters, Principal Doctrines, Vatican sayings, and fragments (1993) edited by Eugene Michael O'Connor, p. 99

- Self-sufficiency is the greatest of all wealth.

- The Essential Epicurus : Letters, Principal Doctrines, Vatican sayings, and fragments (1993) edited by Eugene Michael O'Connor, p. 99

Sovereign Maxims

edit- The 40 "Sovran Maxims" (or "Sovereign Maxims), or "Principal Doctrines" as translated by Robert Drew Hicks

- A happy and eternal being has no trouble himself and brings no trouble upon any other being; hence he is exempt from movements of anger and partiality, for every such movement implies weakness. (1)

- Variant translations:

What is blessed and indestructible has no troubles itself, nor does it give trouble to anyone else, so that it is not affected by feelings of anger or gratitude. For all such things are signs of weakness. (Hutchinson)

The blessed and immortal is itself free from trouble nor does it cause trouble for anyone else; therefore it is not constrained either by anger of favour. For such sentiments exist only in the weak (O'Connor)

A blessed and imperishable being neither has trouble itself nor does it cause trouble for anyone else; therefore, it does not experience anger nor gratitude, for such feelings signify weakness. (unsourced translation)

- Variant translations:

- Οὐκ ἔστιν ἡδέως ζῆν ἄνευ τοῦ φρονίμως καὶ καλῶς καὶ δικαίως, οὐδὲ φρονίμως καὶ καλῶς καὶ δικαίως ἄνευ τοῦ ἡδέως. ὅτῳ δὲ τοῦτο μὴ ὑπάρχει ἐξ οὗ ζῆν φρονίμως, καὶ καλῶς καὶ δικαίως ὑπάρχει, οὐκ ἔστι τοῦτον ἡδέως ζῆν.

- It is impossible to live a pleasant life without living wisely and honorably and justly, and it is impossible to live wisely and honorably and justly without living pleasantly. Whenever any one of these is lacking, when, for instance, the man is not able to live wisely, though he lives honorably and justly, it is impossible for him to live a pleasant life. (5)

- No pleasure is in itself evil, but the things which produce certain pleasures entail annoyances many times greater than the pleasures themselves. (8)

- Variant translation: No pleasure is itself a bad thing, but the things that produce some kinds of pleasure, bring along with them unpleasantness that is much greater than the pleasure itself.

- It is impossible for someone to dispel his fears about the most important matters if he doesn't know the nature of the universe but still gives some credence to myths. So without the study of nature there is no enjoyment of pure pleasure. (12)

- Variant translation: One cannot rid himself of his primal fears if he does not understand the nature of the universe, but instead suspects the truth of some mythical story. So without the study of nature, there can be no enjoyment of pure pleasure. [1]

- The wealth required by nature is limited and is easy to procure; but the wealth required by vain ideals extends to infinity. (15)

- Chance seldom interferes with the wise man; his greatest and highest interests have been, are, and will be, directed by reason throughout his whole life. (16).

- Ὁ δίκαιος ἀταρακτότατος, ὁ δ᾽ ἄδικος πλείστης ταραχῆς γέμων.

- The just man is most free from disturbance, while the unjust is full of the utmost disturbance. (17)

- The flesh receives as unlimited the limits of pleasure; and to provide it requires unlimited time. But the mind, intellectually grasping what the end and limit of the flesh is, and banishing the terrors of the future, procures a complete and perfect life, and we have no longer any need of unlimited time. Nevertheless the mind does not shun pleasure, and even when circumstances make death imminent, the mind does not lack enjoyment of the best life. (20)

- We must consider both the ultimate end and all clear sensory evidence, to which we refer our opinions; for otherwise everything will be full of uncertainty and confusion. (22)

- If you reject absolutely any single sensation without stopping to discriminate with respect to that which awaits confirmation between matter of opinion and that which is already present, whether in sensation or in feelings or in any immediate perception of the mind, you will throw into confusion even the rest of your sensations by your groundless belief and so you will be rejecting the standard of truth altogether. If in your ideas based upon opinion you hastily affirm as true all that awaits confirmation as well as that which does not, you will not escape error, as you will be maintaining complete ambiguity whenever it is a case of judging between right and wrong opinion. (24)

- Of all the means which wisdom acquires to ensure happiness throughout the whole of life, by far the most important is friendship. (28)

- Of our desires some are natural and necessary, others are natural but not necessary; and others are neither natural nor necessary, but are due to groundless opinion. (29)

- Natural justice is a symbol or expression of usefulness, to prevent one person from harming or being harmed by another. (31)

- Variant: Natural justice is a pledge of reciprocal benefit, to prevent one man from harming or being harmed by another.

- Those animals which are incapable of making binding agreements with one another not to inflict nor suffer harm are without either justice or injustice; and likewise for those peoples who either could not or would not form binding agreements not to inflict nor suffer harm. (32)

- It is impossible for a man who secretly violates the terms of the agreement not to harm or be harmed to feel confident that he will remain undiscovered, even if he has already escaped ten thousand times; for until his death he is never sure that he will not be detected. (35)

- Among the things held to be just by law, whatever is proved to be of advantage in men's dealings has the stamp of justice, whether or not it be the same for all; but if a man makes a law and it does not prove to be mutually advantageous, then this is no longer just. And if what is mutually advantageous varies and only for a time corresponds to our concept of justice, nevertheless for that time it is just for those who do not trouble themselves about empty words, but look simply at the facts. (37)

- Where without any change in circumstances the things held to be just by law are seen not to correspond with the concept of justice in actual practice, such laws are not really just; but wherever the laws have ceased to be advantageous because of a change in circumstances, in that case the laws were for that time just when they were advantageous for the mutual dealings of the citizens, and subsequently ceased to be just when they were no longer advantageous. (38)

- Those who were best able to provide themselves with the means of security against their neighbors, being thus in possession of the surest guarantee, passed the most agreeable life in each other's society; and their enjoyment of the fullest intimacy was such that, if one of them died before his time, the survivors did not mourn his death as if it called for sympathy. (40)

Ancient and Modern Celebrated Freethinkers (Half-Hours with the Freethinkers)

edit- by Charles Bradlaugh, A. Collins, and J. Watts (1877) full text

- The end of living, or the ultimate good, which is to be sought for its own sake, according to the universal opinion of mankind, is happiness; yet men, for the most part, fail in the pursuit of this end, either because they do not form a right idea of the nature of happiness, or because they do not make use of proper means to attain it.

- Since it is every man's interest to be happy through the whole of life, it is the wisdom of every one to employ philosophy in the search of felicity without delay; and there cannot be a greater folly, than to be always beginning to live.

- The happiness which belongs to man, is that state in which he enjoys as many of the good things, and suffers as few of the evils incident to human nature as possible; passing his days in a smooth course of permanent tranquility. A wise man, though deprived of sight or hearing, may experience happiness in the enjoyment of the good things which yet remain; and when suffering torture, or laboring under some painful disease, can mitigate the anguish by patience, and can enjoy, in his afflictions, the consciousness of his own constancy.

- Pleasure, or pain, is not only good, or evil, in itself, but the measure of what is good or evil, in every object of desire or aversion; for the ultimate reason why we pursue one thing, and avoid another, is because we expect pleasure from the former, and apprehend pain from the latter. If we sometimes decline a present pleasure, it is not because we are averse to pleasure itself, but because we conceive, that in the present instance, it will be necessarily connected with a greater pain. In like manner, if we sometimes voluntarily submit to a present pain, it is because we judge that it is necessarily connected with a greater pleasure.

- There are two kinds of pleasure: one consisting in a state of rest, in which both body and mind are undisturbed by any kind of pain; the other arising from an agreeable agitation of the senses, producing a correspondent emotion in the soul. It is upon the former of these that the enjoyment of life chiefly depends. Happiness may therefore be said to consist in bodily ease, and mental tranquility.

- When pleasure is asserted to be the end of living, we are not then to understand that violent kind of delight or joy which arises from the gratification of the senses and passions, but merely that placid state of mind, which results from the absence of every cause of pain or uneasiness. Those pleasures, which arise from agitation, are not to be pursued as in themselves the end of living, but as means of arriving at that stable tranquility, in which true happiness consists. It is the office of reason to confine the pursuit of pleasure within the limits of nature, in order to the attainment of that happy state, in which the body is free from every kind of pain, and the mind from all perturbation. This state must not, however, be conceived to be perfect in proportion as it is inactive and torpid, but in proportion as all the functions of life are quietly and pleasantly performed. A happy life neither resembles a rapid torrent, nor a standing pool, but is like a gentle stream, that glides smoothly and silently along.

- This happy state can only be obtained by a prudent care of the body, and a steady government of the mind. The diseases of the body are to be prevented by temperance, or cured by medicine, or rendered tolerable by patience.

- Against the diseases of the mind, philosophy provides sufficient antidotes. The instruments which it employs for this purpose are the virtues; the root of which, whence all the rest proceed, is prudence. This virtue comprehends the whole art of living discreetly, justly, and honorably, and is, in fact, the same thing with wisdom. It instructs men to free their understandings from the clouds of prejudice; to exercise temperance and fortitude in the government of themselves: and to practice justice towards others. Although pleasure, or happiness, which is the end of living, be superior to virtue, which is only the means, it is every one's interest to practice all the virtues; for in a happy life, pleasure can never be separated from virtue.

- A prudent man, in order to secure his tranquility, will consult his natural disposition in the choice of his plan of life. If, for example, he be persuaded that he should be happier in a state of marriage than in celibacy, he ought to marry; but if he be convinced that matrimony would be an impediment to his happiness, he ought to remain single.

- Temperance is that discreet regulation of the desires and passions, by which we are enabled to enjoy pleasures without suffering any consequent inconvenience. They who maintain such a constant self-command, as never to be enticed by the prospect of present indulgence, to do that which will be productive of evil, obtain the truest pleasure by declining pleasure.

- Since, of desires some are natural and necessary; others natural, but not necessary; and others neither natural nor necessary, but the offspring of false judgment; it must be the office of temperance to gratify the first class, as far as nature requires: to restrain the second within the bounds of moderation; and, as to the third, resolutely to oppose, and, if possible, entirely repress them.

- Sobriety, as opposed to inebriety and gluttony, is of admirable use in teaching men that nature is satisfied with a little, and enabling them to content themselves with simple and frugal fare.

- Continence is a branch of temperance, which prevents the diseases, infamy, remorse, and punishment, to which those are exposed, who indulge themselves in unlawful amours.

- Gentleness, as opposed to an irascible temper, greatly contributes to the tranquility and happiness of life, by preserving the mind from perturbation, and arming it against the assaults of calumny and malice.

- A wise man, who puts himself under the government of reason, will be able to receive an injury with calmness, and to treat the person who committed it with lenity; for he will rank injuries among the casual events of life, and will prudently reflect that he can no more stop the natural current of human passions, than he can curb the stormy winds.

- Moderation, in the pursuit of honors or riches, is the only security against disappointment and vexation. A wise man, therefore, will prefer the simplicity of rustic life to the magnificence of courts.

- Fortitude, the virtue which enables us to endure pain, and to banish fear, is of great use in producing tranquility. Philosophy instructs us to pay homage to the gods, not through hope or fear, but from veneration of their superior nature. It moreover enables us to conquer the fear of death, by teaching us that it is no proper object of terror; since, whilst we are, death is not, and when death arrives, we are not: so that it neither concerns the living nor the dead.

- Justice respects man as living in society, and is the common bond without which no society can subsist.

- Nearly allied to justice are the virtues of beneficence, compassion, gratitude, piety, and friendship.

- A true friend will partake of the wants and sorrows of his friend, as if they were his own; if he be in want, he will relieve him; if he be in prison, he will visit him; if he be sick, he will come to him; nay-situations may occur, in which he would not scruple to die for him. It cannot then be doubted, that friendship is one of the most useful means of procuring a secure, tranquil, and happy life.

Disputed

edit- Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil? Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?

- This attribution occurs in chapter 13 (Ioan. Graphei, 1532, p. 494) of the Christian church father's Lactantius's De Ira Dei (c. 318):

- "God," he [Epicurus] says, "either wants to eliminate bad things and cannot,

or can but does not want to,

or neither wishes to nor can,

or both wants to and can.

If he wants to and cannot, then he is weak and this does not apply to god.

If he can but does not want to, then he is spiteful which is equally foreign to god's nature.

If he neither wants to nor can, he is both weak and spiteful, and so not a god.

If he wants to and can, which is the only thing fitting for a god, where then do bad things come from? Or why does he not eliminate them?"

Lactantius, On the Anger of God, 13.19

- "God," he [Epicurus] says, "either wants to eliminate bad things and cannot,

- Charles Bray, in his 1863 The Philosophy of Necessity: Or, Natural Law as Applicable to Moral, Mental, and Social Science quotes Epicurus without citation as saying a variant of the above statement (p. 41) (with "is not omnipotent" for "is impotent"). This quote appeared in "On the proofs of the existence of God: a lecture and answer questions" (1960) by professor Kryvelev I.A. (Крывелёв И.А. О доказательствах бытия божия: лекция и ответы на вопросы. М., 1960). And N. A. Nicholson, in his 1864 Philosophical Papers (p. 40), attributes "the famous questions" to Epicurus, using the wording used earlier by Hume (with "is he" for "he is"). Hume's statement occurs in Book X (p. 186) of his renowned Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, published posthumously in 1779. The character Philo precedes the statement with "Epicurus's old questions are yet unanswered.…". Hume is following the enormously influential Dictionnaire Historique et Critique (1697–1702) of Pierre Bayle, which quotes Lactantius attributing the questions to Epicurus (Desoer, 1820, p. 479).

- There has also arisen a further disputed extension, for which there has been found no published source prior to The Heretic's Handbook of Quotations: Cutting Comments on Burning Issues (1992) by Charles Bufe, p. 186: "Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?"

Quotes about Epicurus

edit- For if they imagine infinite spaces of time before the world, during which God could not have been idle, in like manner they may conceive outside the world infinite realms of space, in which, if any one says that the Omnipotent cannot hold His hand from working, will it not follow that they must adopt Epicurus' dream of innumerable worlds? with this difference only, that he asserts that they are formed and destroyed by the fortuitous movements of atoms, while they will hold that they are made by God's hand, if they maintain that, throughout the boundless immensity of space, stretching interminably in every direction round the world, God cannot rest, and that the worlds which they suppose Him to make cannot be destroyed. ... there is no place beside the world ...no time before the world.

- Augustine of Hippo, The City of God, Book XI, Ch. 5 "That We Ought Not to Seek to Comprehend the Infinite Ages of Time Before the World, Nor the Infinite Realms of Space"

- Verily, no modern atheist, Mr. Huxley included, can outvie Epicurus in materialism; he can but mimic him. And what is his “ protoplasm.” but a rechauffe of the speculations of the Hindu Swabhavikas or Pantheists, who assert that all things, the gods as well as men and animals, are born from Swabhava or their own nature?! As to Epicurus, this is what Lucretius makes him say: “The soul, thus produced, must be material, because we trace it issuing from a material source; because it exists, and exists alone in a material system ; is nourished by material food ; grows with the growth of the body; becomes matured with its maturity; declines with its decay; and hence, whether belonging to man or brute, must die with its death.” Nevertheless, we would remind the reader that Epicurus is here speaking of the Astral Soul, not of Divine Spirit. Still, if we rightly understand the above, Mr. Huxley's “mutton protoplasm” is of a very ancient origin, and can claim for its birthplace, Athens, and for its cradle, the brain of old Epicurus. p. 250

- H. P. Blavatsky, Isis Unveiled, The Veil of Isis, Part 1, Science, (1877)

- Truly says Cudworth that the greatest ignorance of which our modern wiseacres accuse the ancients is their belief in the soul's immortality. Like the old skeptic of Greece, our scientists—to use an expression of the same Dr. Cudworth—are afraid that if they admit spirits and apparitions they must admit a God too; and there is nothing too absurd, he adds, for them to suppose, in order to keep out the existence of God. The great body of ancient materialists, skeptical as they now seem to us, thought otherwise, and Epicurus, who rejected the soul's immortality, believed still in a God, and Demokritus fully conceded the reality of apparitions. The preexistence and God-like powers of the human spirit were believed in by most all the sages of ancient days. p. 251

- H. P. Blavatsky, Isis Unveiled, The Veil of Isis, Part 1, Science, (1877)

- Epicurus says, no life can be pleasant except a virtuous life; and he charges you to avoid whatever maybe calculated to create disquiet in the mind, or give pain to the body.

- Charles Bradlaugh, A. Collins, and J. Watts, in Ancient and Modern Celebrated Freethinkers (Half-Hours with the Freethinkers) (1877)

- We know, that of all living beings man is the best formed, and, as the gods belong to this number, they must have a human form. ... I do not mean to say that the gods have body and blood in them; but I say that they seem as if they had bodies with blood in them. . . , Epicurus, for whom hidden things were as tangible as if he had touched them with his finger, teaches us that gods are not generally visible, but that they are intelligible; that they are not bodies having a certain solidity . . . but that we can recognize them by their passing images; that as there are atoms enough in the infinite space to produce such images, these are produced before us . . . and make us realize what are these happy, immortal beings.

- Cicero in De Natura Deorum – On the Nature of the GodsBook I, Section 18 (45 BC)

- We cannot quote from his own works, in his own words, because, although he wrote very much, only a summary of his writings has come to us uninjured; but his doctrines have been so fully investigated and treated on, both by his opponents and his disciples, that there is no difficulty or doubt as to the principles inculcated in the school of Epicurus....

- Laertius, quoted in Ancient and Modern Celebrated Freethinkers (Half-Hours with the Freethinkers) by Charles Bradlaugh, A. Collins, and J. Watts (1877)

- The sum of his doctrine concerning philosophy, in general, is this: Philosophy is the exercise of reason in the pursuit and attainment of a happy life; whence it follows, that those studies which conduce neither to the acquisition nor the enjoyment of happiness are to be dismissed as of no value. The end of all speculation ought to be, to enable men to judge with certainty what is to be chosen, and what to be avoided, to preserve themselves free from pain, and to secure health of body, and tranquillity of mind. True philosophy is so useful to every man, that the young should apply to it without delay, and the old should never be weary of the pursuit; for no man is either too young or too old to correct and improve his mind, and to study the art of happiness. Happy are they who possess by nature a free and vigorous intellect, and who are born in a country where they can prosecute their inquiries without restraint: for it is philosophy alone which raises a man above vain fears and base passions, and gives him the perfect command of himself.

- Laertius, quoted in Ancient and Modern Celebrated Freethinkers (Half-Hours with the Freethinkers) by Charles Bradlaugh, A. Collins, and J. Watts (1877)

- As nothing ought to be dearer to a philosopher than truth, he should, pursue it by the most direct means, devising no actions himself, nor suffering himself to be imposed upon by the fictions of others, neither poets, orators, nor logicians, making no other use of the rules of rhetoric or grammar, than to enable him to speak or write with accuracy and perspicuity, and always preferring a plain and simple to an ornamented style. Whilst some doubt of everything, and others profess to acknowledge everything, a wise man will embrace such tenets, and only such as are built upon experience, or upon certain and indisputable axioms.

- Laertius, quoted in Ancient and Modern Celebrated Freethinkers (Half-Hours with the Freethinkers) by Charles Bradlaugh, A. Collins, and J. Watts (1877)

- Ergo vivida vis animi pervicit, et extra

Processit longe flammantia moenia mundi

Atque omne immensum peragravit, mente animoque.- So the vital strength of his spirit won through, and he made his way far outside the flaming walls of the world and ranged over the measureless whole, both in mind and spirit.

- Lucretius, in De Rerum Natura, Book I, line 72

Quotes about Epicureans

edit- "The Epicureans in their writings established this precept: always keep in your mind one of those ancients who practiced virtue." - Marcus Aurelius (The Essential Marcus Aurelius)

- "The thought for today is one which I discovered in Epicurus; for I am wont to cross over even into the enemy’s camp – not as a deserter but as a scout. (Letters, 2)" - Seneca (What Seneca Really Said about Epicureanism)

External links

edit- Epicurus at The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Epicurus,Principle Doctrines, at Internet Classics Archive [2]

- Encarta