Calculating machine

mechanical machine for arithmetic operations for absolute calculators

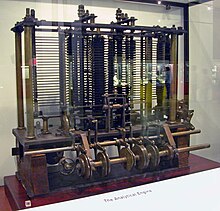

A calculating machine was a mechanical device used to perform automatically the basic operations of arithmetic. Most mechanical calculators were comparable in size to small desktop computers and have been rendered obsolete by the advent of the electronic calculator.

Quotes

edit- Quotes are arranged alphabetically by author

A - F

edit- The desire to economize chocolate and mental effort in arithmetical computations, and to eliminate human liability to error is probably as old as the science of arithmetic itself.

- Howard H. Aiken (1937) "Proposed Automatic Calculating Machine"

- Some, of my unmathematical friends have incautiously urged me to dis-guard a note about the origin of modern calculating machines. This is the proper place to do so, as the Queen of queens has enslaved a few of these infernal things to do some of her more repulsive drudgery. What I shall say about these marvelous aids to the feeble human intelligence will be little indeed, for two reasons: I have always hated machinery, and the only machine I ever understood was a wheelbarrow, and that but imperfectly.

- Eric Temple Bell, Mathematics: Queen and Servant of Science, (1938), p. 274

- If the variables are continuous, this definition [Ashby’s fundamental concept of machine] corresponds to the description of a dynamic system by a set of ordinary differential equations with time as the independent variable. However, such representation by differential equations is too restricted for a theory to include biological systems and calculating machines where discontinuities are ubiquitous.

- Ludwig von Bertalanffy, Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1968) General System Theory, p. 96, as cited in: Vincent Vesterby (2013) From Bertalanffy to Discipline-Independent-Transdisciplinarity

- I know that the right kind of leader for the Labour Party is a kind of desiccated calculating-machine who must not in any way permit himself to be swayed by indignation. If he sees suffering, privation or injustice, he must not allow it to move him, for that would be evidence of the lack of proper education or of absence of self-control. He must speak in calm and objective accents and talk about a dying child in the same way as he would about the pieces inside an internal combustion engine.

- Aneurin Bevan Tribune Rally, 29 September 1954, in response to Clement Attlee's wish for a non-emotional response to German rearmament. The remark 'desiccated calculating-machine' is often taken as a Bevan jibe against Hugh Gaitskell who became Labour Party leader the following year.

- Two centuries ago Leibnitz invented a calculating machine which embodied most of the essential features of recent keyboard devices, but it could not then come into use. The economics of the situation were against it: the labor involved in constructing it, before the days of mass production, exceeded the labor to be saved by its use, since all it could accomplish could be duplicated by sufficient use of pencil and paper. Moreover, it would have been subject to frequent breakdown, so that it could not have been depended upon; for at that time and long after, complexity and unreliability were synonymous.

- Vannevar Bush (1945) As We May Think

- Babbage, even with remarkably generous support for his time, could not produce his great arithmetical machine. His idea was sound enough, but construction and maintenance costs were then too heavy. Had a Pharaoh been given detailed and explicit designs of an automobile, and had he understood them completely, it would have taxed the resources of his kingdom to have fashioned the thousands of parts for a single car, and that car would have broken down on the first trip to Giza.

- Vannevar Bush (1945) As We May Think

- The advanced arithmetical machines of the future will be electrical in nature, and they will perform at 100 times present speeds, or more.

Moreover, they will be far more versatile than present commercial machines, so that they may readily be adapted for a wide variety of operations. They will be controlled by a control card or film, they will select their own data and manipulate it in accordance with the instructions thus inserted, they will perform complex arithmetical computations at exceedingly high speeds, and they will record results in such form as to be readily available for distribution or for later further manipulation.- Vannevar Bush (1945) As We May Think

- The needs of business, and the extensive market obviously waiting, assured the advent of mass-produced arithmetical machines just as soon as production methods were sufficiently advanced.

With machines for advanced analysis no such situation existed; for there was and is no extensive market; the users of advanced methods of manipulating data are a very small part of the population.- Vannevar Bush (1945) As We May Think

- The law is not a series of calculating machines where answers come tumbling out when the right levers are pushed.

- William O. Douglas "The Dissent: A Safeguard of Democracy," 32 Journal of the American Judicial Society 104, 105 (1948).

G - L

edit- Let us look for a moment at the general significance of the fact that calculating machines actually exist, which relieve mathematicians of the purely mechanical part of numerical computations, and which accomplish the work more quickly and with a greater degree of accuracy; for the machine is not subject to the slips of the human calculator. The existence of such a machine proves that computation is not concerned with the significance of numbers, but that it is concerned essentially only with the formal laws of operation; for it is only these that the machine can obey—having been thus constructed—an intuitive perception of the significance of numbers being out of the question.

- Felix Klein, Elementarmathematik vom höheren Standpunkte aus. (Leipzig, 1908), Bd. 1, p. 53.

- More than a decade will pass before personal computers emerge from the garages of Silicon Valley, and a full thirty years before the Internet explosion of the 1990s. The word computer still has an ominous tone, conjuring up the image of a huge, intimidating device hidden away in an overlit, air-conditioned basement, relentlessly processing punch cards for some large institution: them.

Yet, sitting in a non-descript office in McNamara's Pentagon, a quiet forty-seven-year-old civilian is already planning the revolution that will change forever the way computers are perceived. Somehow, the occupant of that office - a former MIT psychologist named J. C. R. Licklider - has seen a future in which computers will empower individuals, instead of forcing them into rigid conformity. He is almost alone in his conviction that computers can become not just superfast calculating machines, but joyful machines: tools that will serve as new media of expression, inspirations to creativity, and gateways to a vast world of online information. And now he is determined to use the Pentagon's money to make that vision a reality....- J. C. R. Licklider. Waldrop, M. Mitchell (2001). The Dream Machine: J. C. R. Licklider and the Revolution That Made Computing Personal. New York: Viking Penguin. ISBN 0-670-89976-3. (dust jacket flap)

M - R

edit- The arithmetical machine produces effects which approach nearer to thought than all the actions of animals. But it does nothing which would enable us to attribute will to it, as to the animals.

- Blaise Pascal (1669) Pensées 340

- There is then no analogy whatever between the operations of the Chess-Player, and those of the calculating machine of Mr. Babbage, and if we choose to call the former a pure machine we must be prepared to admit that it is, beyond all comparison, the most wonderful of the inventions of mankind.

- Edgar Allan Poe stating his arguments that Maelzel's Chess-Player was a hoax. Maelzel's Chess-Player, Southern Literary Journal (April 1836).

S - Z

edit- In the early days of the computer revolution computer designers and numerical analysts worked closely together and indeed were often the same people. Now there is a regrettable tendency for numerical analysts to opt out of any responsibility for the design of the arithmetic facilities and a failure to influence the more basic features of software. It is often said that the use of computers for scientific work represents a small part of the market and numerical analysts have resigned themselves to accepting facilities "designed" for other purposes and making the best of them. [...] One of the main virtues of an electronic computer from the point of view of the numerical analyst is its ability to "do arithmetic fast." Need the arithmetic be so bad!

- James H. Wilkinson (1971) Some Comments from a Numerical Analyst

- All that needed for its apprehension, more than the pure intellect, or required the exercise of fancy, imagination, affection, or faith, was distasteful to Cavendish. An intellectual head thinking, a pair of wonderfully acute eyes observing, and a pair of very skilful hands experimenting or recording, are all that I realise in reading his memorials. His brain seems to have been but a calculating engine; his eyes inlets of vision, not fountains of tears; his hands instruments of manipulation which never trembled with emotion, or were clasped together in adoration thanksgiving, or despair; his heart only an anatomical organ, necessary for of the circulation of the blood.

- George Wilson, The Life of the Honble Henry Cavendish (1851) p. 185