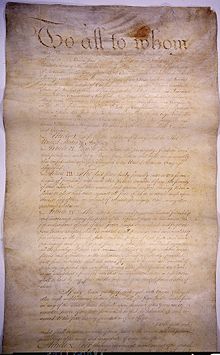

Articles of Confederation

first constitution of the United States (1781–1789)

(Redirected from Articles)

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, created in 1777, was the first governing document of the United States of America. It established a perpetual "Union", with rules on how to govern it. The Articles of Confederation were replaced in the late 1780s by the United States Constitution, which is still in use today.

Quotes from the Articles

editArticle III

edit- The said States hereby severally enter into a firm league of friendship with each other, for their common defense, the security of their liberties, and their mutual and general welfare, binding themselves to assist each other, against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them, or any of them, on account of religion, sovereignty, trade, or any other pretense whatever.

Article IV

edit- The better to secure and perpetuate mutual friendship and intercourse among the people of the different States in this Union, the free inhabitants of each of these States, paupers, vagabonds, and fugitives from justice excepted, shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of free citizens in the several States; and the people of each State shall free ingress and regress to and from any other State, and shall enjoy therein all the privileges of trade and commerce, subject to the same duties, impositions, and restrictions as the inhabitants thereof respectively, provided that such restrictions shall not extend so far as to prevent the removal of property imported into any State, to any other State, of which the owner is an inhabitant; provided also that no imposition, duties or restriction shall be laid by any State, on the property of the United States, or either of them.

Article V

edit- Freedom of speech and debate in Congress shall not be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of Congress, and the members of Congress shall be protected in their persons from arrests or imprisonments, during the time of their going to and from, and attendence on Congress, except for treason, felony, or breach of the peace.

Article XI

edit- Canada acceding to this confederation, and adjoining in the measures of the United States, shall be admitted into, and entitled to all the advantages of this Union; but no other colony shall be admitted into the same, unless such admission be agreed to by nine States.

Quotes about the Articles

editB

edit- Every little school boy is trained to recite the weaknesses and inefficiencies of the Articles of Confederation. It is taken as axiomatic that under them the new nation was falling into anarchy and was only saved by the wisdom and energy of the Convention. … The nation had to be strong to repel invasion, strong to pay to the last loved copper penny the debts of the propertied and the provident ones, strong to keep the unpropertied and improvident from ever using the government to secure their own prosperity at the expense of moneyed capital. … No one suggests that the anxiety of the leaders of the heretofore unquestioned ruling classes desired the revision of the Articles and labored so weightily over a new instrument not because the nation was failing under the Articles, but because it was succeeding only too well. Without intervention from the leaders, reconstruction threatened in time to turn the new nation into an agrarian and proletarian democracy. … All we know is that at a time when the current of political progress was in the direction of agrarian and proletarian democracy, a force hostile to it gripped the nation and imposed upon it a powerful form against which it was never to succeed in doing more than blindly struggle. The liberating virus of the Revolution was definitely expunged, and henceforth if it worked at all it had to work against the State, in opposition to the armed and respectable power of the nation.

- Randolph Bourne, ¶13 of §II of "The State" (1918). Published under "The Development of the American State," The State (Tucson, Arizona: See Sharp Press, 1998), pp. 33–34

G

edit- During the war of the Revolution, and in 1788, the date of the adoption of our national Constitution, there was but one State among the thirteen whose constitution refused the right of suffrage to the negro. That State was South Carolina. Some, it is true, established a property qualification; all made freedom a prerequisite; but none save South Carolina made color a condition of suffrage. The Federal Constitution makes no such distinction, nor did the Articles of Confederation. In the Congress of the Confederation, on the 25th of June, 1778, the fourth article was under discussion. It provided that 'the free inhabitants of each of these States — paupers, vagabonds, and fugitives from justice excepted — shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of free citizens in the several States.' The delegates from South Carolina moved to insert between the words 'free inhabitants' the word 'white', thus denying the privileges and immunities of citizenship to the colored man. According to the rules of the convention, each State had but one vote. Eleven States voted on the question. One was divided; two voted aye; and eight voted no. It was thus early, and almost unanimously, decided that freedom, not color, should be the test of citizenship. No federal legislation prior to 1812 placed any restriction on the right of suffrage in consequence of the color of the citizen. From 1789 to 1812 Congress passed ten separate laws establishing new Territories. In all these, freedom, and not color, was the basis of suffrage.

- James A. Garfield, oration delivered at Ravenna (4 July 1865), Ohio

L

edit- The Union is much older than the Constitution. It was formed, in fact, by the Articles of Association in 1774. It was matured and continued by the Declaration of Independence in 1776. It was further matured, and the faith of all the then thirteen States expressly plighted and engaged that it should be perpetual, by the Articles of Confederation in 1778. And finally, in 1787, one of the declared objects for ordaining and establishing the Constitution was to form a more perfect Union.

- Abraham Lincoln, first inaugural address (4 March 1861)

S

edit- When the Constitution says 'We the People' that's not just a rhetorical flourish. That's a description of the nature of the Union. See Akhil Reed Amar's excellent book The American Constitution: A Biography for this interpretation in full. Why did they do this? Because the founders did not want the national government to be a creature of the states. They had had one of those in the Articles of Confederation, and it didn’t work for them. That’s why the Constitution is very clear in Article VI that it supersedes the states; that's why all federal and state officials MUST swear or affirm their allegiance to the U.S. Constitution, look it up. The nature of the American Union, then, is based on popular sovereignty, the idea that the people have the right to rule. The American people spoke during ratification and created a new federal government in which they vested their sovereignty. The federal government is not merely an agent of the states, as John C. Calhoun asserted; it was not and is not a compact between states. The founders specifically avoided that. So, if a state wants to leave the Union, the only possible way is for 'We the People' to agree to let it go. But there is no specific mechanism for secession in the constitution as it stands. And really, there is no way to read a right of secession into its text. It isn't there, and that's because the Founders never intended for states to break away. Therefore, secession, which would effectively destroy the Constitution, was and is illegal. And Lincoln was simply carrying out his oath of office to 'preserve, protect, and defend' it.

- Christopher Shelley, "Chat-Room" (7 April 2014), Crossroads

U

edit- By [the Articles of Confederation], the Union was solemnly declared to 'be perpetual.' And when these Articles were found to be inadequate to the exigencies of the country, the Constitution was ordained 'to form a more perfect Union.' It is difficult to convey the idea of indissoluble unity more clearly than by these words. What can be indissoluble if a perpetual Union, made more perfect, is not?

- United States Supreme Court, Texas v. White (1869), 74 U.S. 700

W

edit- The citizenship status of blacks was never quite clear. Obviously, they were not quite resident aliens, for they had no country but the United States. The federal government generally avoided taking a stand on black citizenship when the subject arose. A few blacks got federal passports implying that they were citizens... The Articles of Confederation stated that 'the free inhabitants of these states... shall be entitled to all privileges of immunities of free citizens in the several states', and Congress voted down South Carolina's proposal to insert the word 'white' into this clause. Chief Justice Taney, in the infamous 1857 Dred Scott decision, asserted that blacks had never been, and could never be, citizens of the United States. He was wrong.

- Thomas West, Vindicating the Founders (2001), p. 27