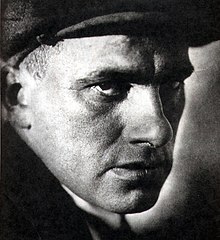

Vladimir Mayakovsky

Russian and Soviet poet (1893–1930)

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (19 July 1893 NS – 14 April 1930) was a Georgian-born Russian playwright, screenwriter and poet. A Bolshevik activist before 1917, he became the pre-eminent poet of the Russian Revolution and one of the leading literary figures of the Futurist movement.

Quotes

edit- On the pavement

of my trampled soul

the steps of madmen

weave the prints of rude crude words.- "1" (1913); translation from Vladimir Mayakovsky. The Bedbug and Selected Poetry. Ed. with introd. by Patricia Blake. Trans. by Max Hayward and George Reavey. Reprint. Bloomington, In: Indiana University Press, 1975 [1960]. ISBN 0-253-20189-6. p. 53.

- Tramp squares with rebellious treading!

Up heads! As proud peaks be seen!

In the second flood we are spreading

Every city on earth will be clean.- "Our March" (1917); translation from C. M. Bowra (ed.) A Book of Russian Verse (London: Macmillan, 1943) p. 125

- Art must not be concentrated in dead shrines called museums. lt must be spread everywhere – on the streets, in the trams, factories, workshops, and in the workers' homes.

- "Shrine or Factory?" (1918); translation from Mikhail Anikst et al. (eds.) Soviet Commercial Design of the Twenties (New York: Abbeville Press, 1987) p. 15

- A rhyme's

…

a barrel of dynamite.

A line is a fuse

that's lit.

The line smoulders,

the rhyme explodes –

and by a stanza

a city

is blown to bits.- "A Conversation with the Inspector of Taxes about Poetry" (1926); translation from Chris Jenks Visual Culture (London: Routledge, 1995) pp. 86-7

- I want to be understood by my country,

but if I fail to be understood –

what then?,

I shall pass through my native land

to one side,

like a shower

of slanting rain.- "Back Home!", first version (1926); translation from Patricia Blake (ed.) The Bedbug and Selected Poetry (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975) p. 36

- Love

for us

is no paradise of arbors —

to us

love tells us, humming,

that the stalled motor

of the heart

has started to work

again.- "Letter from Paris to Comrade Kostorov on the Nature of Love" (1928); translation from Patricia Blake (ed.) The Bedbug and Selected Poetry (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975) p. 213

- Agitprop

sticks

in my teeth too,

and I'd rather

compose

romances for you –

more profit in it

and more charm.

But I

subdued

myself,

setting my heel

on the throat

of my own song.- "At the Top of My Voice" (1929-30); translation from Patricia Blake (ed.) The Bedbug and Selected Poetry (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975) pp. 223-5

- In parade deploying

the armies of my pages,

I shall inspect

the regiments in line.

Heavy as lead,

my verses at attention stand,

ready for death

and for immortal fame.- "At the Top of My Voice" (1929-30); translation from Patricia Blake (ed.) The Bedbug and Selected Poetry (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975) p. 227

- Love's ship has foundered on the rocks of life.

We're quits: stupid to draw up a list

of mutual sorrows, hurts and pains.- Untitled last poem found after his death; translation from Martin Seymour-Smith Guide to Modern World Literature (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1975) vol. 4, p. 235

- I understand the power and the alarm of words –

Not those that they applaud from theatre-boxes,

but those which make coffins break from bearers

and on their four oak legs walk right away.- Untitled last poem found after his death; translation from Martin Seymour-Smith Guide to Modern World Literature (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1975) vol. 4, p. 235

The Cloud in Trousers (1915)

editQuotations are cited from Patricia Blake (ed.) The Bedbug and Selected Poetry (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975).

- No gray hairs streak my soul,

no grandfatherly fondness there!

I shake the world with the might of my voice,

and walk – handsome,

twentytwoyearold.- Page 61.

- If you wish,

I shall grow irreproachably tender:

not a man, but a cloud in trousers!- Page 61.

- Hey, you!

Heaven!

Off with your hat!

I am coming!

Not a sound.

The universe sleeps,

its huge paw curled

upon a star-infested ear.- Page 109.

Disputed

edit- Art is not a mirror to hold up to society, but a hammer with which to shape it.

- Attributed to Vladimir Mayakovsky in The Political Psyche (1993) by Andrew Samuels, p. 9; attributed to Bertolt Brecht in Paulo Freire : A Critical Encounter (1993) by Peter McLaren and Peter Leonard, p. 80

- Variant translation: Art is not a mirror held up to society, but a hammer with which to shape it.

Quotes about Mayakovsky

edit- One evening Ilyich (Lenin) wanted to see for himself how the young people were getting on in the communes. We decided to visit our young friend Varya Armand who lived in a commune for art school students. I think that we made the visit on the day Kropotkin was buried, in 1921. It was a hungry year, but the young people were filled with enthusiasm. The people in the commune slept practically on bare boards, they had neither bread nor salt. "But we do have cereals," said a radiantfaced member of the commune. With this cereal they boiled a good porridge for Ilyich. Ilyich looked at the young people, at the radiant faces of the boys and girls who crowded around him, and their joy was reflected in his face. They showed him their naive drawings, explained their meaning. and bombarded him with questions. And he, smiling, evaded answering and parried by asking questions of his own: "What do you read? Do you read Pushkin?" -- "Oh, no," said someone, "after all he was a bourgeois; we read Mayakovsky." Ilyich smiled. "I think," he said, "that Pushkin is better." After this Ilyich took a more favourable view of Mayakovsky. Whenever the poet's name was mentioned he recalled the young art students who, full of life and gladness, and ready to die for the Soviet system, were unable to find words in the contemporary language with which to express themselves, and sought the answer in the obscure verse of Mayakovsky. Later, however, Ilyich once praised Mayakovsky for the verse in which he ridiculed Soviet red tape.

- He stands with one foot on Mont Blanc and with the other on the Elbrus. His voice out-thunders thunder. What is the wonder that…the proportions of earthly things vanish and that no difference is left between the small and the great?…No doubt this hyperbolic style reflects in some measure the frenzy of our time. But this does not provide it with an overall artistic justification. It is impossible to out-clamour war and revolution, but it is easy to get hoarse in the attempt.

- Leon Trotsky Literature and Revolution (1925); translation from Isaac Deutscher The Prophet Unarmed: Trotsky, 1921-1929 (London: Verso, 2003) p. 157

- He was perhaps the only tolerable propaganda poet of all time: he meant it, and the energy he put into it was, as is frequently said, demonic.

- Martin Seymour-Smith Guide to Modern World Literature (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1975) vol. 4, p. 234

- Incomprehensible rubbish.

- Vladimir Ilyich Lenin; translation from Margaret Drabble (ed.) The Oxford Companion to English Literature (Oxford: OUP, 1995) p. 643.

- Of Mayaskovsky's 1920 poem, 150,000,000

- Mayakovsky was and is the best and most talented poet of our Soviet era. Indifference to his memory and works is a crime.

- Memorandum by Joseph Stalin; translation from Katerina Clark et al. (trans. Marian Schwartz) Soviet Culture and Power: A History in Documents, 1917-1953 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007) p. 288

- With this man, the newness of our times was climatically and uniquely in his blood. His very strangeness was one with the strangeness of the age, an age still half unrealised.

- Boris Pasternak Safe Conduct (1931); translation from Geoffrey Grigson (ed.) The Concise Encyclopedia of Modern World Literature (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1971) p. 239.

- You don't have to be a poet, but you do have to be a citizen. Well, Mayakovsky was not a citizen, he was a lackey, who served Stalin faithfully. He added his babble to the magnification of the immortal image of the leader and teacher.

- Solomon Volkov (ed.) Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich (New York: Limelight, 2006) p. 248.