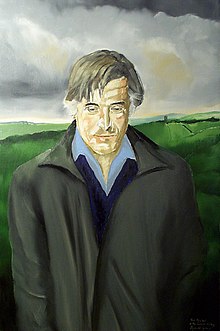

Ted Hughes

English poet and children's writer (1930-1998)

Edward James Hughes, OM (17 August 1930 – 28 October 1998) was an English poet, translator and children's writer who for the last 14 years of his life occupied the role of Poet Laureate. He was the husband of Sylvia Plath, who influenced his writing style.

Blade-light, luminous black and emerald,

Flexing like the lens of a mad eye.

- See also:

- The Iron Giant (1999 film), based on his novel The Iron Man (1968)

Quotes

edit- However rootedly national it may be, poetry is less and less the prisoner of its own language. It is beginning to represent as an ambassador, something far greater than itself. Or perhaps, it is only now being heard for what, among other thngs, it is — a universal language of understanding, coherent behind the many languages in which we can all hope to meet. … We now give more serious weight to the words of a country's poets than to the words of its politicians — though we know the latter may interfere more drastically with our lives. Religions, ideologies, mercantile competition divide us. The essential solidarity of the very diverse poets of the world, besides being mysterious fact is one we can be thankful for, since its terms are exclusively those of love, understanding and patience. It is one of the few spontaneous guarantees of possible unity that mankind can show, and the revival of an appetite for poetry is like a revival of an appetite for all man's saner possibilities, and a revulsion from the materialist cataclysms of recent years and the worse ones which the difference of nations threatens for the years ahead.

The idea of global unity is not new, but the absolute necessity of it has only just arrived, like a sudden radical alteration of the sun, and we shall have to adapt or disappear. If the nations are ever to make a working synthesis of their ferocious contradictions, the plan will be created in spirit before it can be formulated or accepted in political fact. And it is in poetry that we can refresh our hope that such a unity is occupying people's imaginations everywhere, since poetry is the voice of spirit and imagination and all that is potential, as well as of the healing benevolence that used to be the privilege of the gods.- Poetry International Programme note (1967); also in Selected Translations (2006), edited by Daniel Weissbort, p. 10

The Hawk in the Rain (1957)

edit- Cold, delicately as the dark snow,

A fox's nose touches twig, leaf;

Two eyes serve a movement, that now

And again now, and now, and now

Sets neat prints into the snow.- "The Thought-Fox", line 10

- With a sudden sharp hot stink of fox,

It enters the dark hole of the head.

The window is starless still; the clock ticks,

The page is printed.- "The Thought-Fox", line 21

- This house has been far out at sea all night,

The woods crashing through darkness, the booming hills,

Winds stampeding the fields under the window

Floundering black astride and blinding wetTill day rose; then under an orange sky

The hills had new places, and wind wielded

Blade-light, luminous black and emerald,

Flexing like the lens of a mad eye.- "Wind"

- The world rolls under the long thrust of his heel.

Over the cage floor the horizons come.- "The Jaguar"

Lupercal (1960)

editOr fly up, and revolve it all slowly –

I kill where I please because it is all mine.

There is no sophistry in my body:

My manners are tearing off heads –

The allotment of death.

- Pike, three inches long, perfect

Pike in all parts, green tigering the gold.

Killers from the egg: the malevolent aged grin.- "Pike", line 1

- The jaws' hooked clamp and fangs

Not to be changed at this date;

A life subdued to its instrument.- "Pike", line 13

- Stilled legendary depth:

It was as deep as England. It held

Pike too immense to stir, so immense and old

That past nightfall I dared not cast.- "Pike", line 33

- I sit in the top of the wood, my eyes closed.

Inaction, no falsifying dream

Between my hooked head and hooked feet:

Or in sleep rehearse perfect kills and eat.- "Hawk Roosting", line 1

- It took the whole of Creation

To produce my foot, my each feather:

Now I hold Creation in my foot.

Or fly up, and revolve it all slowly –

I kill where I please because it is all mine.

There is no sophistry in my body:

My manners are tearing off heads –

The allotment of death.- "Hawk Roosting", line 10

- Nothing has changed since I began.

My eye has permitted no change.

I am going to keep things like this.- "Hawk Roosting", line 22

- The gash in its throat was shocking, but not pathetic.

- "View of a Pig"

- The deeps are cold:

In that darkness camaraderie does not hold:

Nothing touches but, clutching, devours.- "Relic"

Wodwo (1967)

edit- The brassy wood-pigeons

Bubble their colourful voices, and the sun

Rises upon a world well-tried and old.- "Stealing Trout on a May Morning"

- No, the serpent did not

Seduce Eve to the apple.

All that's simply

Corruption of the facts.Adam ate the apple.

Eve ate Adam.

The serpent ate Eve.

This is the dark intestine.The serpent, meanwhile,

Sleeps his meal off in Paradise—

Smiling to hear

God's querulous calling.- "Theology"

The Iron Man (1968)

edit- The Iron Man : A Children's Story in Five Nights; also published as The Iron Giant : A Story in Five Nights

- The Iron Man came to the top of the cliff. How far had he walked? Nobody knows. Where did he come from? Nobody knows. How was he made? Nobody knows. Taller than a house the Iron Man stood at the top of the cliff, at the very brink, in the darkness.

- Ch. 1 : The Coming of the Iron Man

- He swayed in the strong wind that pressed against his back. He swayed forward, on the brink of the high cliff. And his right foot, his enormous iron right foot, lifted-up, out, into space, and the Iron Man stepped forward, off the cliff, into nothingness.

- Ch. 1 : The Coming of the Iron Man

- Nobody knew the Iron Man had fallen.

Night passed.- Ch. 1 : The Coming of the Iron Man

- Who owns the whole rainy, stony earth? Death.

Who owns all of space? Death.- "Examination at the Womb-door"

The Paris Review interview

edit- Interviewed by Drue Heinz in "Ted Hughes, The Art of Poetry No. 71" in The Paris Review No. 134 (Spring 1995)

- From the age of about eight or nine I read just about every comic book available in England. At that time my parents owned a newsagent’s shop. I took the comics from the shop, read them, and put them back. That went on until I was twelve or thirteen. Then my mother brought in a sort of children’s encyclopedia that included sections of folklore. Little folktales. I remember the shock of reading those stories. I could not believe that such wonderful things existed. … throughout your life you have certain literary shocks, and the folktales were my first. From then on I began to collect folklore, folk stories, and mythology. That became my craze.

- Poems get to the point where they are stronger than you are. They come up from some other depth and they find a place on the page. You can never find that depth again, that same kind of authority and voice. I might feel I would like to change something about them, but they’re still stronger than I am and I cannot.

- I think it’s the shock of every writer’s life when their first book is published. The shock of their lives. One has somehow to adjust from being anonymous, a figure in ambush, working from concealment, to being and working in full public view. It had an enormous effect on me. My impression was that I had suddenly walked into a wall of heavy hostile fire.

- I’ve sometimes wondered if it wouldn’t be a good idea to write under a few pseudonyms. Keep several quite different lines of writing going. Like Fernando Pessoa, the Portuguese poet who tried four different poetic personalities. They all worked simultaneously. He simply lived with the four. What does Eliot say? “Dance, dance, / Like a dancing bear, / Cry like a parrot, chatter like an ape, / To find expression.” It’s certainly limiting to confine your writing to one public persona, because the moment you publish your own name you lose freedom.

- The danger, I suppose, of using pseudonyms is that it interferes with that desirable process—the unification of the personality. Goethe said that even the writing of plays, dividing the imagination up among different fictional personalities, damaged what he valued — the mind’s wholeness. I wonder what he meant exactly, since he also described his mode of thinking as imagined conversations with various people. Maybe the pseudonyms, like other personalities conjured up in a dramatic work, can be a preliminary stage of identifying and exploring new parts of yourself. Then the next stage would be to incorporate them in the unifying process. Accept responsibility for them. Maybe that’s what Yeats meant by seeking his opposite. The great Sufi master Ibn el-Arabi described the essential method of spiritual advancement as an inner conversation with the personalities that seem to exist beyond what you regard as your own limits . . . getting those personalities to tell you what you did not know, or what you could not easily conceive of within your habitual limits. This is commonplace in some therapies, of course.

- Many writers write a great deal, but very few write more than a very little of the real thing. So most writing must be displaced activity. When cockerels confront each other and daren’t fight, they busily start pecking imaginary grains off to the side. That’s displaced activity. Much of what we do at any level is a bit like that, I fancy. But hard to know which is which. On the other hand, the machinery has to be kept running. The big problem for those who write verse is keeping the machine running without simply exercising evasion of the real confrontation. If Ulanova, the ballerina, missed one day of practice, she couldn’t get back to peak fitness without a week of hard work. Dickens said the same about his writing—if he missed a day he needed a week of hard slog to get back into the flow.

- Goethe called his work one big confession, didn’t he? Looking at his work in the broadest sense, you could say the same of Shakespeare: a total self-examination and self-accusation, a total confession—very naked, I think, when you look into it. Maybe it’s the same with any writing that has real poetic life. Maybe all poetry, insofar as it moves us and connects with us, is a revealing of something that the writer doesn’t actually want to say but desperately needs to communicate, to be delivered of. Perhaps it’s the need to keep it hidden that makes it poetic—makes it poetry. The writer daren’t actually put it into words, so it leaks out obliquely, smuggled through analogies. We think we’re writing something to amuse, but we’re actually saying something we desperately need to share.

- Why do human beings need to confess? Maybe if you don’t have that secret confession, you don’t have a poem — don’t even have a story. Don’t have a writer. If most poetry doesn’t seem to be in any sense confessional, it’s because the strategy of concealment, of obliquity, can be so compulsive that it’s almost entirely successful.

- Sylvia went furthest in the sense that her secret was most dangerous to her. She desperately needed to reveal it. You can’t overestimate her compulsion to write like that. She had to write those things — even against her most vital interests. She died before she knew what The Bell Jar and the Ariel poems were going to do to her life, but she had to get them out. She had to tell everybody . . . like those Native American groups who periodically told everything that was wrong and painful in their lives in the presence of the whole tribe. It was no good doing it in secret; it had to be done in front of everybody else. Maybe that’s why poets go to such lengths to get their poems published. It’s no good whispering them to a priest or a confessional. And it’s not for fame, because they go on doing it after they’ve learned what fame amounts to. No, until the revelation’s actually published, the poet feels no release. In all that, Sylvia was an extreme case, I think.

- I see now that when we met, my writing, like hers, left its old path and started to circle and search. To me, of course, she was not only herself — she was America and American literature in person. I don’t know what I was to her. Apart from the more monumental classics — Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, and so on — my background reading was utterly different from hers. But our minds soon became two parts of one operation. We dreamed a lot of shared or complementary dreams. Our telepathy was intrusive. I don’t know whether our verse exchanged much, if we influenced one another that way — not in the early days. Maybe others see that differently. Our methods were not the same. Hers was to collect a heap of vivid objects and good words and make a pattern; the pattern would be projected from somewhere deep inside, from her very distinctly evolved myth. It appears distinctly evolved to a reader now — despite having been totally unconscious to her then. My method was to find a thread end and draw the rest out of a hidden tangle. Her method was more painterly, mine more narrative, perhaps.

- There are certain things that are just impressive, aren’t there? One stone can be impressive and the stones around it aren’t. It’s the same with animals. Some, for some reason, are strangely impressive. They just get into you in a strange way. Certain birds obviously have this extra quality that fascinates your attention. Obviously hawks have always done that for me, as a great many others have — not only impressive in themselves but also in that they’ve accumulated an enormous literature making them even more impressive. And crows too. Crows are the central bird in many mythologies. The crow is at every extreme, lives on every piece of land on earth, the most intelligent bird.

- Every poem that works is like a metaphor of the whole mind writing, the solution of all the oppositions and imbalances going on at that time. When the mind finds the balance of all those things and projects it, that’s a poem. It’s a kind of hologram of the mental condition at that moment, which then immediately changes and moves on to some other sort of balance and rearrangement. What counts is that it be a symbol of that momentary wholeness. That’s how I see it.

- The idea occurred to me that art was perhaps this—the psychological component of the autoimmune system. It works on the artist as a healing. But it works on others too, as a medicine. Hence our great, insatiable thirst for it. However it comes out — whether a design in a carpet, a painting on a wall, the shaping of a doorway — we recognize that medicinal element because of the instant healing effect, and we call it art. It consoles and heals something in us. That’s why that aspect of things is so important, and why what we want to preserve in civilizations and societies is their art — because it’s a living medicine that we can still use. It still works. We feel it working. Prose, narratives, etcetera, can carry this healing. Poetry does it more intensely. Music, maybe, most intensely of all.

Quotes about Hughes

edit- No death outside my immediate family has left me feeling more bereft. No death in my lifetime has hurt poets more. He was a tower of tenderness and strength, a great arch under which the least of poetry's children could enter and feel secure. His creative powers were, as Shakespeare said, still crescent. By his death, the veil of poetry is rent and the walls of learning broken.

- Seamus Heaney, speaking at Hughes' funeral (3 November 1998), as quoted in Savage Gods, Silver Ghosts : In the Wild with Ted Hughes (2009) by Ehor Boyanowsky

- His voice is commanding. He is often invited to read his work, the flow of his language enlivening the text. In appearance he is impressive, and yet there is very little aggression or intimidation in his look. Indeed, one admirer has said that her first thought sitting opposite him was that this was what God should look like “when you get there.”

- Hughes began (The Hawk in the Rain, 1957; Lupercal, 1960) as an elemental poet of power; he was inchoate, but fruitfully aware both of the brute force of creation and of the natural world. Then a naive (q.v.) poet — he began to assume a mantic role; he has now turned into (Crow, 1970) a pretentious, coffee-table poet, a mindless celebrant of instinct.

- Martin Seymour-Smith Guide to Modern World Literature (1973; 1975) vol. 1, p. 358

- The sky split apart in malice

Stars rattled like pans on a shelf

Crow shat on Buckingham Palace

God pissed Himself.- Philip Larkin, in parody of Hughes commemorating the Queen's Silver Jubilee, in a letter to Charles Monteith, March 2, 1978; published in Anthony Thwaite (ed.) Selected Letters of Philip Larkin (1992) p. 581

- Orghast aims to be a leveller of audiences by appealing not to semantic athleticism but to the instinctive recognition of a "mental state" within a sound. One can hardly imagine a bolder challenge to the limits of narrative.

- Tom Stoppard, on the play by Hughes using an invented language, as quoted in Review of Orghast at Persepolis at Complete Review