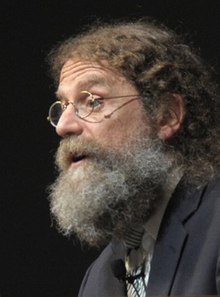

Robert Sapolsky

American neuroendocrinology researcher (b. 1957)

Robert Sapolsky (born April 6, 1957) is a biologist and author. He is a professor at Stanford University.

Quotes

edit- I love science, and it pains me to think that so many are terrified of the subject or feel that choosing science means that you cannot also choose compassion, or the arts, or be awed by nature. Science is not meant to cure us of mystery, but to reinvent and reinvigorate it.

- Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers (3rd ed., 2004), Preface, p. XII

- Get it wrong, and we call it a cult. Get it right, in the right time and the right place, and maybe, for the next few millennia, people won't have to go to work on your birthday.

The Trouble With Testosterone: And Other Essays on the Biology of the Human Predicament (1997)

edit- The Trouble With Testosterone: And Other Essays on the Biology of the Human Predicament. New York: A Touchstone Book, Simon & Schuster. 1998. LCC QP360.S268 1997. ISBN 9780684834092.

- This is a classic case of what is often called physics envy, the disease among scientists where the behavioral biologists fear their discipline lacks the rigor of physiology, the physiologists wish for the techniques of the biochemists, the biochemists covet the clarity of the answers revealed by molecular biologists, all the way down the down until you get to the physicists, who confer only with God.

- "The Trouble With Testosterone", p. 152

- We are a fine species with some potential. Yet we are racked by sickening amounts of violence. Unless we are hermints, we feel the threat of it, often as a daily shadow. And regardless of where we hide, should our leaders push the button, we will all be lost in a final global violence.

- "The Trouble With Testosterone", pp. 157–158

- The ones who I train to become scientists go at it like the warriors they should be, overturning existing knowledge and reigning paradigms, each discovery a murder of their scientific ancestors. And if I have trained them well, I must derive whatever satisfaction I can from the inevitability of becoming their Oedipal target someday.

- "The Dissolution of Ego Boundaries and the Fit of My Father's Shirt", p. 226

- The notion of the psychopathology of the shaman works just as readily in understanding the roots of major Western religions as well.

- "Circling the Blanket for God", p. 255

- The far-from-original point I will try to make now should seem obvious: There is an unsettling similarity between the rituals of the obsessive-compulsive and the rituals of the observantly religious.

- "Circling the Blanket for God", p. 263

Stress, Neurodegeneration and Individual Differences (2001)

edit- Most of us don't collapse into puddles of stress-related disease.

- Finish this lecture, go outside, and unexpectedly get gored by an elephant, and you are going to secrete glucocorticoids. There's no way out of it. You cannot psychologically reframe your experience and decide you did not like the shirt, here's an excuse to throw it out — that sort of thing.

- What's the punch line here? Physiologically, it doesn't come cheap being a bastard 24 hours a day.

- We are not getting our ulcers being chased by Saber-tooth tigers, we're inventing our social stressors — and if some baboons are good at dealing with this, we should be able to as well. Insofar as we're smart enough to have invented this stuff and stupid enough to fall for it, we have the potential to be wise enough to keep the stuff in perspective.

Emperor Has No Clothes Award acceptance speech (2003)

edit- "Emperor Has No Clothes Award" acceptance speech at the Freedom From Religion Foundation convention, San Diego (23 November 2003), Excerpt published as "Belief and Biology" in Freethought Today Vol. 20 No. 3 (April 2003)

- Why do we have schizophrenia in every culture on this planet? From an evolutionary perspective, schizophrenia is not a cool thing to have. ... Schizophrenia is not an adaptive trait. You can show this formally: schizophrenics have a lower rate of leaving copies of their genes in the next generation than unaffected siblings. By the rules, by the economics of evolution, this is a maladaptive trait. Yet, it chugs along at a one to two percent rate in every culture on this planet.

So what's the adaptive advantage of schizophrenia? It has to do with a classic truism — this business that sometimes you have a genetic trait which in the full-blown version is a disaster, but the partial version is good news.

- Schizophrenics have a whole lot of trouble telling the level of abstraction of a story. They're always biased in the direction of interpreting things more concretely than is actually the case. You would take a schizopohrenic and say, "Okay, what do apples, bananas and oranges have in common?" and they would say, "They all are multi-syllabic words."

You say "Well, that's true. Do they have anything else in common?" and they say, "Yes, they actually all contain letters that form closed loops."

This is not seeing the trees instead of the forest, this is seeing the bark on the trees, this very concreteness.

- In the 1930s an anthropologist named Paul Radin first described it as "shamans being half mad," shamans being "healed madmen." This fits exactly. It's the shamans who are moving separate from everyone else, living alone, who talk with the dead, who speak in tongues, who go out with the full moon and turn into a hyena overnight, and that sort of stuff. It's the shamans who have all this metamagical thinking. When you look at traditional human society, they all have shamans. What's very clear, though, is they all have a limit on the number of shamans. That is this classic sort of balanced selection of evolution. There is a need for this subtype — but not too many.

The critical thing with schizotypal shamanism is, it is not uncontrolled the way it is in the schizophrenic. This is not somebody babbling in tongues all the time in the middle of the hunt. This is someone babbling during the right ceremony. This is not somebody hearing voices all the time, this is somebody hearing voices only at the right point. It's a milder, more controlled version.

Shamans are not evolutionarily unfit. Shamans are not leaving fewer copies of their genes. These are some of the most powerful, honored members of society. This is where the selection is coming from. … In order to have a couple of shamans on hand in your group, you're willing to put up with the occasional third cousin who's schizophrenic.

- Western religions, all the leading religions, have this schizotypalism shot through them from top to bottom. It's that same exact principle: it's great having one of these guys, but we sure wouldn't want to have three of them in our tribe. Overdo it, and our schizotypalism in the Western religious setting is what we call a "cult," and there you are in the realm of a Charles Manson or a David Koresh or a Jim Jones. You can only do post-hoc forensic psychiatry on Koresh and Jones, but Charles Manson is a diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic. But get it just right, and people are gonna get the day off from work on your birthday for millennia to come. [laughter] This is great! I think this is the first time I've ever said that line without somebody getting up and leaving in a huff from the audience. It's very nice being here.

- Orthodox Judaism has this amazing set of rules: everyday there's a bunch of strictures of things you're supposed to do, a bunch you're not supposed to do, and the number you're supposed to do is the same number as the number of bones in the body. The number that you're not supposed to do is the same number as the number of days in the year. The amazing thing is, nobody knows what the rules are! Talmudic rabbis have been scratching each others' eyes out for centuries arguing over which rules go into the 613. The numbers are more important than the content. It is sheer numerology.

- I am a reasonably emotional person, and I see no reason why that's incompatible with being a scientist. Even if we learn about how everything works, that doesn't mean anything at all. You can reduce how an impala leaps to a bunch of biomechanical equations. You can turn Bach into contrapuntal equations, and that doesn't reduce in the slightest our capacity to be moved by a gazelle leaping or Bach thundering. There is no reason to be less moved by nature around us simply because it's revealed to have more layers of complexity than we first observed.

The more important reason why people shouldn't be afraid is, we're never going to inadvertently go and explain everything. We may learn everything about something, and we may learn something about everything, but we're never going to learn everything about everything. When you study science, and especially these realms of the biology of what makes us human, what's clear is that every time you find out something, that brings up ten new questions, and half of those are better questions than you started with.

- The purpose of science in understanding who we are as humans is not to rob us of our sense of mystery, not to cure us of our sense of mystery. The purpose of science is to constantly reinvent and reinvigorate that mystery. To always use it in a context where we are helping people in trying to resist the forces of ideology that we are all familiar with.

Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst (2017)

edit- Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. New York: Penguin Press. 2017. LCC QP351 .S27 2017. ISBN 9781594205071.

- We build theologies around violence, elect leaders who excel at it, and in the case of so many women, preferentially mate with champions of human combat. When it’s the "right" type of aggression, we love it.

- "Introduction", p. 9

- Oxytocin, the luv hormone, makes us more prosocial to Us and worse to everyone else. That’s not generic prosociality. That’s ethnocentrism and xenophobia.

- "Hours to Days Before", p. 109

- Ecosystems majorly shape culture — but then that culture can be exported and persist in radically different places for millennia. Stated most straightforwardly, most of earth’s humans have inherited their beliefs about the nature of birth and death and everything in between and thereafter from preliterate Middle Eastern pastoralists.

- "Centuries to Millennia Before", p. 313

- Like so many other animals, we have an often-frantic need to conform, belong, and obey. Such conformity can be markedly maladaptive, as we forgo better solutions in the name of the foolishness of the crowd.

- "Hierarchy, Obedience, and Resistance", p. 451

The Neuroscience Behind Behavior (2017)

edit- We're only a couple of hundreds of years into understanding that epilepsy is a neurological disease and not a demonic possession. We're only about 50 years into understanding that certain types of learning disabilities are micro malformations in the cortex in people with dyslexia and not laziness or lack of motivation. The vast majority of these factoids [presented in the book] are 10, 20 years old, and all that's gonna happen is we're gonna learn more and more of that stuff. And what we're going to learn more and more is to recognise extents to which we're biological organisms and our behaviours have to be evaluated in that realm. For my money, what that eventually does is make words like "soul" or "evil" utterly absurd and medieval, but it also makes words like "punishment" or "justice" very questionable, as well. I think it will require an enormous reshaping of how we think we deal with the most damaging of human behaviours, because none of it can be thought of outside the context of biology.[1]

- From the very moment of your life, culture is leaving an imprint on who you are.

- Arts & Ideas -- Published by : Show_More Feb, 7, 2018