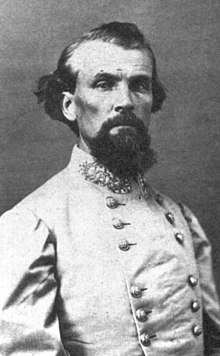

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Confederate States Army general (1821-1877)

Nathan Bedford Forrest (13 July 1821 – 29 October 1877) was a prominent Confederate Army general during the American Civil War and the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan from 1867 to 1869. Before the war, Forrest amassed substantial wealth as a cotton plantation owner, horse and cattle trader, real estate broker, and slave trader. In June 1861, he enlisted in the Confederate Army and became one of the few soldiers during the war to enlist as a private and be promoted to general without any prior military training. An expert cavalry leader, Forrest was given command of a corps and established new doctrines for mobile forces, earning the nickname "The Wizard of the Saddle".

Quotes

edit- This fight is against slavery; if we lose it, you will be made free.

- As quoted in Report of the Joint Select Committee.

- "After all, I think Forrest was the most remarkable man our Civil War produced on either side...He had never read a military book in his life, knew nothing about tactics, could not even drill a company, but had a genius of strategy which was original, and to me incomprehensible."

- Regarding Forrest's millitary genius, William T. Sherman w:The Life of General Nathan Bedford Forrest, by John Allan Wyeth, p.635.

- I am opposed to it under any and all circumstances, and in our convention urged our party not to commit themselves at all upon the subject.

- Regarding black voting, as quoted in Report of the Joint Select Committee.

- The river was dyed with the blood of the slaughtered for two hundred yards. The approximate loss was upward of five hundred killed, but few of the officers escaping. My loss was about twenty killed. It is hoped that these facts will demonstrate to the Northern people that Negro soldiers cannot cope with Southerners.

- Regarding the Fort Pillow massacre, as quoted in Personal Memoirs, by U.S. Grant, (Library of America, 1990), p. 483.

1860s

edit- Get there first with the most men.

- Reported by General Basil W. Duke and Richard Taylor

- Often erroneously reported as "Git thar fustest with the most mostest." In The Quote Verifier : Who Said What, Where, and When (2006) by Ralph Keyes, p. 272, the phrase he used has also been reported to have been "I always make it a rule to get there first with the most men" and "I just took the short cut and got there first with the most men."

- Every moment lost is worth the life of a thousand men.

- Said to Braxton Bragg at Chickamauga, September 18-20, 1863. As quoted in May I Quote You, General Forrest? by Randall Bedwell.

- Boys, do you hear that musketry and that artillery? It means that our friends are falling by the hundreds at the hands of the enemy, and here we are guarding a damned creek! Let's go and help them. What do you say?

- Said to his men at Shiloh, 1862. As quoted in May I Quote You, General Forrest? by Randall Bedwell.

- War means fighting, and fighting means killing.

- As quoted in May I Quote You, General Forrest? by Randall Bedwell.

- If you surrender, you shall be treated as prisoners of war, but if I have to storm your works, you may expect no quarter.

- As quoted in May I Quote You, General Forrest? by Randall Bedwell.

- Does the damned fool want to be blown up? Well, blow him up then. Give him hell, Captain Morton- as hot as you've got it, too.

- At Athens, Alabama, 1864. As quoted in May I Quote You, General Forrest? by Randall Bedwell.

- There is no doubt we could soon wipe old Sherman off the face of the earth, John, if they'd give me enough men and you enough guns.

- To Captain John Morton, 1864. As quoted in May I Quote You, General Forrest? by Randall Bedwell.

- I've got no respect for a young man who won't join the colors.

- As quoted in May I Quote You, General Forrest? by Randall Bedwell.

- I'll officer you.

- Said by Forrest, with saber drawn, to a young lieutenant who would not help in dousing flames on supply wagons set on fire by Union troops on their retreat to Memphis. As quoted in May I Quote You, General Forrest? by Randall Bedwell.

- That we are beaten is a self-evident fact, and any further resistance on our part would be justly regarded as the very height of folly and rashness.

- Forrest to his men, 1865. As quoted in May I Quote You, General Forrest? by Randall Bedwell.

- Preserve untarnished the reputation you have so nobly won.

- Part of Forrest's last address to his men, 1865. As quoted in May I Quote You, General Forrest? by Randall Bedwell.

- Men, you may all do as you damn please, but I'm a-goin' home.

- Forrest to Charles Clark, Governor of Mississippi and Isham G. Harris, former Governor of Tennessee, in response to the request that he keep fighting. As quoted in May I Quote You, General Forrest? by Randall Bedwell.

Farewell address (1865)

edit- Forrest's farewell address to his men (May 9, 1865), Headquarters, Forrest's Cavalry Corps, Gainesville, Alabama. As quoted in May I Quote You, General Forrest? by Randall Bedwell.

- Civil war, such as you have just passed through naturally engenders feelings of animosity, hatred, and revenge. It is our duty to divest ourselves of all such feelings; and as far as it is in our power to do so, to cultivate friendly feelings towards those with whom we have so long contended, and heretofore so widely, but honestly, differed. Neighborhood feuds, personal animosities, and private differences should be blotted out; and, when you return home, a manly, straightforward course of conduct will secure the respect of your enemies. Whatever your responsibilities may be to Government, to society, or to individuals meet them like men.

- The attempt made to establish a separate and independent Confederation has failed; but the consciousness of having done your duty faithfully, and to the end, will, in some measure, repay for the hardships you have undergone. In bidding you farewell, rest assured that you carry with you my best wishes for your future welfare and happiness. Without, in any way, referring to the merits of the Cause in which we have been engaged, your courage and determination, as exhibited on many hard-fought fields, has elicited the respect and admiration of friend and foe. And I now cheerfully and gratefully acknowledge my indebtedness to the officers and men of my command whose zeal, fidelity and unflinching bravery have been the great source of my past success in arms.

- I have never, on the field of battle, sent you where I was unwilling to go myself; nor would I now advise you to a course which I felt myself unwilling to pursue. You have been good soldiers, you can be good citizens. Obey the laws, preserve your honor, and the Government to which you have surrendered can afford to be, and will be, magnanimous.

1870s

editLetter to war veterans (1875)

edit- However much we differed with them while public enemies, and were at war, we must admit that they fought gallantly for the preservation of the government which we fought to destroy, which is now ours, was that of our fathers, and must be that of our children. Though our love for that government was for a while supplanted by the exasperation springing out of a sense of violated rights and the conflict of battle, yet our love for free government, justly administered, has not perished, and must grow strong in the hearts of brave men who have learned to appreciate the noble qualities of the true soldier.

- Let us all, then, join their comrades who live, in spreading flowers over the graves of these dead Federal soldiers, before the whole American people, as a peace offering to the nation, as a testimonial of our respect for their devotion to duty, and as a tribute from patriots, as we have ever been, to the great Republic, and in honor of the flag against which we fought, and under which they fell, nobly maintaining the honor of that flag. It is our duty to honor the government for which they died, and if called upon, to fight for the flag we could not conquer.

Speech before the Pole-Bearers Association (1875)

edit- Ladies and gentlemen, I accept the flowers as a memento of reconciliation between the white and colored races of the southern states. I accept it more particularly as it comes from a colored lady, for if there is any one on God's earth who loves the ladies I believe it is myself.

- This day is a day that is proud to me, having occupied the position that I did for the past twelve years, and been misunderstood by your race. This is the first opportunity I have had during that time to say that I am your friend. I am here a representative of the southern people, one more slandered and maligned than any man in the nation.

- I will say to you and to the colored race that men who bore arms and followed the flag of the Confederacy are, with very few exceptions, your friends. I have an opportunity of saying what I have always felt - that I am your friend, for my interests are your interests, and your interests are my interests. We were born on the same soil, breathe the same air, and live in the same land. Why, then, can we not live as brothers? I will say that when the war broke out I felt it my duty to stand by my people. When the time came I did the best I could, and I don't believe I flickered. I came here with the jeers of some white people, who think that I am doing wrong. I believe that I can exert some influence, and do much to assist the people in strengthening fraternal relations, and shall do all in my power to bring about peace. It has always been my motto to elevate every man- to depress none.

- I want to elevate you to take positions in law offices, in stores, on farms, and wherever you are capable of going.

- I have not said anything about politics today. I don't propose to say anything about politics. You have a right to elect whom you please; vote for the man you think best, and I think, when that is done, that you and I are freemen. Do as you consider right and honest in electing men for office. I did not come here to make you a long speech, although invited to do so by you. I am not much of a speaker, and my business prevented me from preparing myself. I came to meet you as friends, and welcome you to the white people. I want you to come nearer to us. When I can serve you I will do so. We have but one flag, one country; let us stand together. We may differ in color, but not in sentiment. Use your best judgement in selecting men for office and vote as you think right.

- Many things have been said about me which are wrong, and which white and black persons here, who stood by me through the war, can contradict. I have been in the heat of battle when colored men, asked me to protect them. I have placed myself between them and the bullets of my men, and told them they should be kept unharmed. Go to work, be industrious, live honestly and act truly, and when you are oppressed I'll come to your relief. I thank you, ladies and gentlemen, for this opportunity you have afforded me to be with you, and to assure you that I am with you in heart and in hand.

Quotes about Forrest

edit- The urgent need for supplies sometimes dictated audacious raids by Confederate squadrons. General Nathan Forrest, a serious, brooding man, with an instinct for war though he had little of the formal training received by most of his brother officers, launched a daring attack on Grant's rail communications at Jackson, Tennessee. Forrest, who ordered his men to "charge both ways" whenever surrounded by the enemy, did such a good job tearing up the track, burning trestles and taking whatever could be captured, that the railroad was useless for some time.

- Lamont Buchanan, A Pictorial History of the Confederacy (1951), p. 157

- Forrest ... used his horsemen as a modern general would use motorized infantry. He liked horses because he liked fast movement, and his mounted men could get from here to there much faster than any infantry could; but when they reached the field they usually tied their horses to trees and fought on foot, and they were as good as the very best infantry

- Bruce Catton, The Civil War (1971), New York: American Heritage Press, p. 160.

- Shortly before Independence Day, 1867, Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest, second only to Robert E. Lee as a hero of the South, presided over the inauguration of the racist, xenophobic hate group that today is the one still point in the otherwise changing universe of America's extreme right- the Invisible Empire of the Ku Klux Klan. The Kluxers actually had started around Pulaski, Tennessee, in 1865, when six young Confederate veterans returned home and decided to start a "club" to cheer up their friends and neighbors who still hadn't shaken off the gloom of Appomattox. As legend has it, the six original Klansmen decided to dress up in costumes because it was faddish at the time to masquerade. With the South ravaged by the war, however, the only costumes they could find were the stiff linen sheets and bedding that their womenfolk had carefully husbanded. When the "pranksters" and their horses- also covered in white linen- rode about the Tennessee countryside on their revels, the racist legend has it, blacks became terrified, thinking they were being visited by the ghosts of rebel war dead. In 1867, however, General Forrest joined the Klan, took its reins, and transformed the group into a guerilla cadre dedicated to opposing "Northern oppression". Since the rules imposed for Reconstruction called for granting blacks the vote and allowing majority governments to form, much of the Klan's efforts focused on keeping former slaves from going to the polls. To that end Forrest and his troops developed the tactics of hate that latter-day Klansmen emulate today. Crosses were burned; blacks were told not to vote; lynchings were held in the dark of night. The Klan was anti-black for obvious reasons. After all, for Klansmen, the Civil War never ended.

- James Coates, Armed and Dangerous: The Rise of the Survivalist Right (1987), p. 28-29

- Like the neo-Nazi Silent Brotherhood (Bruder Schweigen), the Klan had a complex and highly secret rule book full of hidden meanings. It was called the Invisible Empire, for example, because the day Forrest held his seminal meeting at the Maxwell House he had presented a letter from Robert E. Lee saying that Lee supported the Klan but desired to remain "invisible" in its affairs. The leader was designated the Imperial Wizard because General Forrest had been nicknamed the "horse wizard" while a cavalry officer.

- James Coates, Armed and Dangerous: The Rise of the Survivalist Right (1987), p. 30

- In fact, in recognition of the desperate condition of far too many of that yeomanry, Union and Confederate authorities actually cooperated in places for their relief. In February 1865 a cartel was agreed between Northern General George H. Thomas and the Rebel cavalry commander General Nathan Bedford Forrest that the railroad track between their lines would be left unmolested so that destitute and starving citizens of northern Mississippi and Alabama could send some of their cotton north in exchange for desperately needed Yankee corn.

- William C. Davis, Look Away! A History of the Confederate States of America (2002), p. 248

- Comrades, we are ordered to meet to revise our constitution and by-laws; it is in the hands of an able committee ably, I trust, they have perfected their labors, but while here assembled there is one incident that has transpired upon which I wish to throw your disapproval and have recorded in our archives, although performed by as gallant a cavalryman as ever used sabre over an enemy’s brain; yet let us prove that the old esprit du corps still lives, and that we endorse no action unworthy of a Southern gentleman. I speak of the address delivered before a black and tan audience by Gen. N. B. Forrest. With what a glow of enthusiasm and thrill of pride have I not perued the campaigns of Gen. Forrest’s cavalry, their heroic deeds, their sufferings and their successes under the leadership of one whom I always considered (in my poor judgment) second only to out immortal Hampton? And now to mar all the lustre attached to his name, his brain is turned by the civilities of a mulatto wench who presented him with a bouquet of roses. We would rather have sent him a car filled with the rarest exotics plucked from the dizziest peaks of the Himalayas or the perilous fastness of the Andes than he should have thus befouled the fair home of one of the Confederacy's most daring general officers. What can his object be? Ah! General Forrest!

- Wherefore be it resolved, that we, the Survivor’s Association of the Cavalry of the Confederate States, in meeting assembled at Augusta, Ga., do hereby express our unmitigated disapproval of any such sentiments as those expressed by Gen. N. B. Forrest at a meeting of the Pole Bearers Society of Memphis, Tennessee, and that we allow no man to advocate, or even hint to the world, before any public assemblage, that he dare associate our mother’s, wives’ daughters’ or sisters’ names in the same category that he classes the females of the negro race, without, at least, expressing out disapprobation.

- My God, men, will you see them kill your general? I will go to his rescue if not a man follows me!

- Colonel McCulloch to his men when Forrest was engaged in hand-to-hand fighting with Union troops at Okolona, Mississippi. As quoted in May I Quote You, General Forrest? by Randall Bedwell.

- General Forrest was not cruel, nor necessarily severe, but he would not be trifled with.

- Anonymous officer under Forrest's command, as quoted in May I Quote You, General Forrest? by Randall Bedwell.

- The affair at Fort Pillow was simply an orgy of death, a mass lynching to satisfy the basest of conduct – intentional murder – for the vilest of reasons – racism and personal enmity.

- Richard Fuchs, as quoted in An Unerring Fire: The Massacre At Fort Pillow (2002), Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole, p. 14.

- In Memphis, last week, a number of Federal officers and soldiers participated at the decoration of Confederate graves. As a result, Generals Pillow and Forrest addressed a letter through the Memphis papers to surviving Confederate soldiers and veterans of 1812, Florida and Mexico, requesting them to participate in the Federal ceremonies on Sunday last.

- Galveston Daily News (3 June 1875).

- So did Forrest really join the Ku Klux Klan? Yes, he did. Was he really Grand Wizard of the group? Yes, he was. How do we know this? Because the old Klansmen who were there tell us so... By 1875, Tennessee was well on its way to re-establishing the antebellum social and racial order, and groups like the Pole Bearers posed little real challenge to the re-assertion of white power in the state. Men like Forrest could afford to be magnanimous with their words.

- Andy Hall, "Nathan Bedford Forrest Joins the Klan" (11 December 2011), Dead Confederates: A Civil War Era Blog.

- According to Confederate ideology, blacks liked slavery; nevertheless, to avert revolts and runaways, the Confederate states passed the 'twenty nigger law', exempting from military conscription one white man as overseer for every twenty slaves. Throughout the war, Confederates withheld as much as a third of their fighting forces from the front lines and scattered them throughout areas with large slave populations to prevent slave uprisings. When the United States allowed African Americans to enlist, Confederates were forced by their ideology to assert that it would not work; blacks would hardly fight like white men. The undeniable bravery of the 54th Massachusetts and other black regiments disproved the idea of black inferiority. Then came the incongruity of truly beastly behavior by southern whites towards captured black soldiers, such as the infamous Fort Pillow massacre by troops under Nathan Bedford Forrest, who crucified black prisoners on tent frames and then burned them alive, all in the name of preserving white civilization.

- James Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong (2007), New York: New Press, pp. 224–226.

- Massacring surrendered black troops was consistent with Forrest's character. Forrest biography Brian Wills notes that black opponents always inflamed Forrest. After his successful raid at Murfreesboro for instance, a Confederate officer brought before Forrest 'a mulatto man, who was the servant to one of the officers in the Union forces.' Forrest cursed him and asked what he was doing there. The man replied that he was a free man, not a slave, came out as the servant to an officer, whom he named. Forrest drew his pistol and blew the man's brains out. The Confederate officer, who knew the man from Pennsylvania and had never been enslaved, 'denounced the act as one of cold-blooded murder and declared that he would never again serve under Forrest,' according to Wills. Instead of the ‘Forrest Rested Here’ marker on the way into Murfreesboro, Tennessee might erect a marker telling this incident on the way out–'Forrest Murders African American, July 13, 1862'. Such a marker would tell much more history than ‘Rested,’ but it too will not get put up soon in Tennessee.

- James Loewen, Lies Across America: What American Historic Sites Get Wrong (1999), pp. 239–240. Also mentioned in A Battle from the Start (1993), by Brian S. Wills, New York: Harper, pp. 192, 215, 373.

- We have infinitely more respect for Longstreet, who fraternizes with negro men on public occasions, with the pay for the treason to his race in his pocket, than with Forrest and Pillow, who equalize with the negro women, with only 'futures' in payment.

- Macon Weekly Telegraph (20 July 1875).

- It is in connection with one of the most atrocious and cold-blooded massacres that ever disgraced civilized warfare that his name will for ever be inseparably associated. 'Fort Pillow Forrest' was the title which the deed conferred upon him, and by this he will be remembered by the present generation, and by it he will pass into history. The massacre occurred on the 12th of April, 1864. Fort Pillow is 65 miles above Memphis, and its capture was effected during Forrest's celebrated raid through Tennessee, a State which was at the time practically in possession of the Union forces.

- "Death of Gen. Forrest" (29 October 1877), by The New York Times.

- His last notable public appearance was on the Fourth of July in Memphis, when he appeared before the colored people at their celebration, was publicly presented with a bouquet by them as a mark of peace and reconciliation, and made a friendly speech in reply. In this he once more took occasion to defend himself and his war record, and to declare that he was a hearty friend of the colored race.

- As quoted in "Death of Gen. Forrest" (29 October 1877), by The New York Times.

- Follow Forrest to the death if it costs 10,000 lives and breaks the Treasury. There will never be peace in Tennessee till Forrest is dead.

- General William T. Sherman of the Union Army. As quoted in May I Quote You, General Forrest? by Randall Bedwell.

- Nathan Bedford Forrest is overrated. Nathan Bedford Forrest usually gets knocked by historians for his role in the Ku Klux Klan, but praised by tacticians for the battles he won. So why is he here? Forrest often times won battles when his focus should have been elsewhere. For example, he had a great victory Brices Crossroads and faked out A. J. Smith near Memphis after losing the Battle of Tupelo, but won such glory during the time he was supposed to be destroying Sherman's supply lines, an even more important task critical to the CSA war effort. He similarly could do little against John Schofield after the Spring Hill escape.

- John A. Tures, as quoted in "William T. Sherman and Nathan Bedford Forrest: Civil War Criminals" (10 June 2015), by J.A. Tures, The Huffington Post.

- Similarly, he failed to defeat Yankees near Paducah, which might have made Union generals recall significant forces to defend against a raid into Ohio and other Northern states. But he was able to massacre a small force of White Tennesseans and African American soldiers at Ft. Pillow, which only inflamed Northern passions against Southern troops, which by and large didn't kill prisoners as Forrest did. Northerners were less likely to surrender to Confederates now, and prisoner exchanges that broke down the previous year (because the CSA would not release black soldiers and their white officers) never resumed. Whenever Forrest won, other Southerners lost.

- John A. Tures, as quoted in "William T. Sherman and Nathan Bedford Forrest: Civil War Criminals" (10 June 2015), by J.A. Tures, The Huffington Post.

- It is interesting that after the Civil War, both men sought to team up together when war looked likely to occur with Spain over Cuba in 1873. According to Eddy W. Davison, Forrest offered his services to Sherman, who wrote the War Department a glowing recommendation of Forrest's capabilities. It's probably because Sherman and Forrest were two peas in a pod, falsely lionized by their "accomplishments" in the Civil War, who seemed to fare better against the unarmed than the armed. They are two reasons we seem to have unresolved post-Civil War issues.

- John A. Tures, as quoted in "William T. Sherman and Nathan Bedford Forrest: Civil War Criminals" (10 June 2015), by J.A. Tures, The Huffington Post.