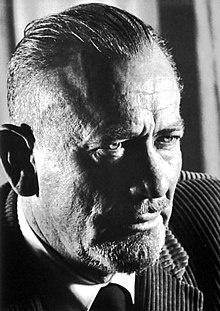

John Steinbeck

American writer (1902–1968)

John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. (27 February 1902 – 20 December 1968) was an American writer. A recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962, his works include the novella Of Mice and Men (1937) and the novel The Grapes of Wrath (1939, Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, 1940), both of which examine the lives of the working class and migrant workers during the Great Depression.

- See also:

Quotes

edit- We are lonesome animals. We spend all our life trying to be less lonesome. One of our ancient methods is to tell a story begging the listener to say — and to feel — ”Yes, that’s the way it is, or at least that’s the way I feel it. You’re not as alone as you thought.”

- “In Awe of Words,” The Exonian, 75th anniversary edition, Exeter University (1930)

- The discipline of the written word punishes both stupidity and dishonesty.

- “In Awe of Words,” The Exonian, 75th anniversary edition, Exeter University (1930)

- In every bit of honest writing in the world … there is a base theme. Try to understand men, if you understand each other you will be kind to each other. Knowing a man well never leads to hate and nearly always leads to love. There are shorter means, many of them. There is writing promoting social change, writing punishing injustice, writing in celebration of heroism, but always that base theme. Try to understand each other.

- Journal entry (1938), quoted in the Introduction to a 1994 edition of Of Mice and Men by Susan Shillinglaw, p. vii

- I must go over into the interior valleys. … There are five thousand families starving to death over there, not just hungry but actually starving. The government is trying to feed them and get medical attention to them, with the Fascist group of utilities and banks and huge growers sabotaging the thing all along the line, and yelling for a balanced budget. In one tent there were twenty people quarantined for small pox and two of the women are to have babies in that tent this week. I've tied into the thing from the first and I must get down there and see it and see if I can do something to knock these murderers on the heads.

Do you know what they're afraid of? They think that if these people are allowed to live in camps with proper sanitary facilities they will organize, and that is the bugbear of the large landowner and the corporate farmer. The states and counties will give them nothing because they are outsiders. But the crops of any part of this state could not be harvested without them. … The death of children by starvation in our valleys is simply staggering. … I'll do what I can. … Funny how mean and little books become in the face of such tragedies.- Letter to Elizabeth Otis (1938), as quoted in Conversations with John Steinbeck (1988) edited by Thomas Fensch, p. 37

- You see this book is finished and it is a bad book and I must get rid of it. It can't be printed. It is bad because it isn't honest. Oh! the incidents all happened but — I'm not telling as much of the truth about them as I know. In satire you have to restrict the picture and I just can't do satire. I've written three books now that were dishonest because they were less than the best that I could do. One you never saw because I burned it the day I finished it. … My whole work drive has been aimed at making people understand each other and then I deliberately write this book, the aim of which is to cause hatred through partial understanding. My father would have called it a smart-alec book. It was full of tricks to make people ridiculous. If I can't do better I have slipped badly. And that I won't admit — yet.

- Letter to Elizabeth Otis, expressing dissatisfaction with L'Affaire Lettuceburg — a satire he abandoned in favor of work on what became The Grapes of Wrath (c. mid-May 1938) as quoted in Conversations with John Steinbeck (1988) edited by Thomas Fensch, p. 38

- It is a nice thing to be working and believing in my work again. I hope I can keep the drive. I only feel whole and well when it is this way.

- Letter to Elizabeth Otis, once he had begun The Grapes of Wrath (1 June 1938)

- For the first time I am working on a book that is not limited and that will take every bit of experience and thought and feeling that I have.

- Journal entry (11 June 1938), published in Working Days : The Journals of The Grapes of Wrath, 1938-1941 (1990) edited by Robert DeMott

- Boileau said that Kings, Gods and Heroes only were fit subjects for literature. The writer can only write about what he admires. Present-day kings aren't very inspiring, the gods are on a vacation and about the only heroes left are the scientists and the poor … And since our race admires gallantry, the writer will deal with it where he finds it. He finds it in the struggling poor now.

- Radio interview (1939) quoted in Introduction by Robert DeMott to a 1992 edition of The Grapes of Wrath

- Ideas are like rabbits. You get a couple and learn how to handle them, and pretty soon you have a dozen.

- Interview with Robert van Gelder (April 1947), as quoted in John Steinbeck : A Biography (1994) by Jay Parini

- All hell has broken loose. I admit our Russian is limited, but we can say hello, come in, you are beautiful, oh no you don't. … So in our pride we ordered for breakfast an omelet, toast and coffee and what has just arrived is a tomato salad with onions, a dish of pickles, a big slice of watermelon and two bottles of cream soda. Something has slipped badly.

- On difficulties while traveling in the USSR (20 August 1947), in Steinbeck : A Life in Letters (1976)

- No little appetite or pain, no carelessness or meanness in him escaped her; no thought or dream or longing in him ever reached her. And yet several times in her life she had seen the stars.

- The Moon Is Down (1942), p. 7

- I have come to believe that a great teacher is a great artist and that there are as few as there are any other great artists. It might even be the greatest of the arts since the medium is the human mind and spirit.

- "…like captured fireflies" (1955); also published in America and Americans and Selected Nonfiction (2003), p. 142

- One man was so mad at me that he ended his letter: “Beware. You will never get out of this world alive.”

- “The Mail I’ve Seen” Saturday Review (3 August 1956)

- If I wanted to destroy a nation, I would give it too much and I would have it on its knees, miserable, greedy and sick.

- Letter to Adlai Stevenson (5 November 1959), quoted in The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer : A Biography (1984), by Jackson J. Benson, p. 876

- Yesterday in Muir Woods that dog lifted his leg on a tree that was 20 feet across, 80 feet high and a 1,000 years old — what's left in life for that poor dog?

- Circa 1961, dining at Enrico's in San Francisco with a group including Herb Caen and Howard Gossage (presumably a brief stopover made during the westernmost portion of the road trip described in Travels with Charley), prompting Gossage's tentative reply, "W-w-well, he can always t-t-teach," and, shortly thereafter, quoted by Caen in the Chronicle; later reproduced in "In With the In Crowd, Here and Abroad" by Barnaby Conrad, The San Francisco Examiner (10 July 1988)

- Writers are a little below clowns and a little above trained seals.

- Quote magazine (18 June 1961)

- The profession of book-writing makes horse-racing seem like a solid, stable business.

- Newsweek (24 December 1962)

- The President must be greater than anyone else, but not better than anyone else. We subject him and his family to close and constant scrutiny and denounce them for things that we ourselves do every day. A Presidential slip of the tongue, a slight error in judgment — social, political, or ethical — can raise a storm of protest. We give the President more work than a man can do, more responsibility than a man should take, more pressure than a man can bear. We abuse him often and rarely praise him. We wear him out, use him up, eat him up. And with all this, Americans have a love for the President that goes beyond loyalty or party nationality; he is ours, and we exercise the right to destroy him.

- America and Americans (1966)

- Syntax, my lad. It has been restored to the highest place in the republic.

- When asked his reaction to John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address

- Quoted by Atlantic magazine (November 1969)

- Unless a reviewer has the courage to give you unqualified praise, I say ignore the bastard.

- As quoted by John Kenneth Galbraith in the Introduction to The Affluent Society (1977 edition)

- Woody is just Woody. Thousands of people do not know he has any other name. He is just a voice and a guitar. He sings the songs of a people and I suspect that he is, in a way, that people. Harsh voiced and nasal, his guitar hanging like a tire iron on a rusty rim, there is nothing sweet about Woody, and there is nothing sweet about the songs he sings. But there is something more important for those who will listen. There is the will of the people to endure and fight against oppression. I think we call this the American spirit.

- As quoted in Woody Guthrie: A Life (1981) by Joe Klein, p. 160

Of Mice and Men (1937)

edit- Well, God knows he don't need any brains to buck barley bags. But don't you try to put nothing over, Milton. I got my eye on you.

- The boss to George in Ch. 2; "buck" here means to work at lifting and throwing the sacks of barley

- What the hell kind of bed you giving us, anyways. We don’t want no pants rabbits.

- Ch. 2, p. 20; "pants rabbits" refers to fleas, lice or crabs.

- "Well, that glove's fulla vaseline."

"Vaseline? What the hell for?"

"Well, I tell ya what — Curley says he's keepin' that hand soft for his wife."- Ch. 2, p. 29

- Ain't many guys travel around together. I don’t know why. Maybe ever’body in the whole damn world is scared of each other.

- Ch. 2, p. 35

- A powerful, big-stomached man came into the bunkhouse.

- Ch. 2, p. 35

- His ear heard more than is said to him, and his slow speech had overtones not of thought, but of understanding beyond thought.

- Ch. 2, p. 36

- Guy don't need no sense to be a nice fella. Seems to me sometimes it jus' works the other way around. Take a real smart guy and he ain't hardly ever a nice fella.

- Ch. 3, p. 41

- We could live offa the fatta the lan’.

- Lennie in Ch. 3, p. 57

- Books ain't no good. A guy needs somebody — to be near him. A guy goes nuts if he ain't got nobody.

- Ch. 4, p. 72

- They come, an' they quit an' go on; an' every damn one of 'em's got a little piece of land in his head. An' never a God damn one of 'em ever gets it. Just like heaven. Ever'body wants a little piece of lan'. I read plenty of books out here. Nobody never gets to heaven, and nobody gets no land. It's just in their head.

- Ch. 4, p. 74

- I seen too many guys with land in their head. They never get none under their hand.

- Ch. 4, p. 75

- You watch your place, nigger. I could get you strung up on a tree so easy, it ain't even funny.

- Curley's wife in Ch. 4, p. 80

- You ain't worth a greased lack pin to ram you into hell.

- Ch. 6, p. 101

The Grapes of Wrath (1939)

edit- For man, unlike anything organic or inorganic in the universe, grows beyond his work, walks up the stairs of his concepts, emerges ahead of his accomplishments.

- Ch. 14

- How can we live without our lives? How will we know it’s us without our past?

- Prayer never brought in no side-meat. Takes a shoat to bring in pork.

Cannery Row (1945)

edit- Cannery Row in Monterey in California is a poem, a stink, a grating noise, a quality of light, a tone, a habit, a nostalgia, a dream. [Opening sentence.]

- "It has always seemed strange to me," said Doc. "The things we admire in men, kindness and generosity, openness, honesty, understanding and feeling are the concomitants of failure in our system. And those traits we detest, sharpness, greed, acquisitiveness, meanness, egotism and self-interest are the traits of success."

The Wayward Bus (1947)

edit- He was a fine steady man, Juan Chicoy, part Mexican and part Irish, perhaps fifty years old, with clear black eyes, a good head of hair, and a dark and handsome face. Mrs Chicoy was insanely in love with him and a little afraid of him too, because he was a man, and there aren't very many of them, as Alice Chicoy had found out. There aren't very many of them in the world, as everyone finds out sooner or later.

- Ch. 1

- Mr. Pritchard was a businessman, president of a medium-sized corporation. He was never alone. His business was conducted by groups of men like himself who joined together in clubs so that no foreign element or idea could enter. His religious life was again his lodge and his church, both of which were screened and protected. One night a week he played poker with men so exactly like himself that the game was fairly even, and from this fact his group was convinced that they were very fine poker players. Wherever he went he was not one man but a unit in a corporation, a unit in a club, in a lodge, in a church, in a political party. His thoughts and ideas were never subjected to criticism since he willingly associated only with people like himself. He read a newspaper written by and for his group. The books that came into his house were chosen by a committee which deleted material that might irritate him. He hated foreign countries and foreigners because it was difficult to find his counterpart in them. He did not want to stand out from his group. He would like to have risen to the top of it and be admired by it; but it would not occur to him to leave it. At occasional stags where naked girls danced on the tables and sat in great glasses of wine, Mr. Pritchard howled with laughter and drank the wine, but five hundred Mr. Pritchards were there with him.

- Ch. 3

- Her body and her mind were sluggish and lazy, and deep down she fought a tired envy of the people who, so she thought, experienced good things while she went through life a gray cloud in a gray room. Having few actual perceptions, she lived by rules. Education is good. Self-control is necessary. Everything in its time and place. Travel is broadening. And it was this last axiom which had forced her finally on the vacation to Mexico.

- About Bernice Pritchard in Ch. 5

- He wondered why he stayed with her. Just pure laziness, he guessed. He didn't want to go through the emotional turmoil of leaving her. In spite of himself he'd worry about her and it was too much trouble. He'd need another woman right away and that took a lot of talking and arguing and persuading. It was different just to lay a girl but he would need a woman around, and that was the difference. You got used to one and it was less trouble.[…]

But there was another reason too. She loved him. She really did. And he knew it. And you can't leave a thing like that. It's a structure and it has an architecture, and you can't leave it without tearing off a piece of yourself. So if you want to remain whole you stay no matter how much you may dislike staying. Juan was not a man who fooled himself very much.- Ch. 8

- He didn't believe in psychiatrists, he said. But actually he did believe in them, so much that he was afraid of them.

- Ch. 13. "He" is Elliot Pritchard.

- She envied Camille. Camille was a tramp, Mildred thought. And things were so much easier for a tramp. There was no conscience, no sense of loss, nothing but a wonderful, relaxed, stretching-cat selfishness. She could go to bed with anyone she wanted to and never see him again and have no feeling of loss or insecurity about it. That was the way Mildred thought it was with Camille. She wished she could be that way, and she knew she couldn't. Couldn't because of her mother. And the unbidden thought entered her mind—if her mother were only dead Mildred's life would be so much simpler. She could have a secret little place to live somewhere. Almost fiercely, she brushed the thought away. "What a foul thing to think," she said to herself ceremoniously. But it was a dream she often had.

- Ch. 13. Mildred is the daughter of Elliot and Bernice Pritchard.

- For it is said that humans are never satisfied, that you give them one thing and they want something more. And this is said in disparagement, whereas it is one of the greatest talents the species has and one that has made it superior to animals that are satisfied with what they have.

- Ch. III

- A plan is a real thing, and things projected are experienced. A plan once made and visualized becomes a reality along with other realities—never to be destroyed but easily to be attacked.

- Ch. III

- Luck, you see, brings bitter friends.

- Ch. III

- For every man in the world functions to the best of his ability, and no one does less than his best, no matter what he may think about it.

- Ch. IV

- He had said, "I am a man," and that meant certain things to Juana. It meant that he was half insane and half god. It meant that Kino would drive his strength against a mountain and plunge his strength against the sea. Juana, in her woman's soul, knew that the mountain would stand while the man broke himself; that the sea would surge while the man drowned in it. And yet it was this thing that made him a man, half insane and half god, and Juana had need of a man; she could not live without a man. Although she might be puzzled by these differences between man and woman, she knew them and accepted them and needed them. Of course she would follow him, there was no question of that. Sometimes the quality of woman, the reason, the caution, the sense of preservation, could cut through Kino's manness and save them all.

- Ch. V

Burning Bright (1950)

edit- "When you argue with a child," she said warmly, "you give a good argument and the child says yah, yah! You understand him and he doesn't listen, so the child wins."

- Mordeen to Victor in Act One: The Circus

- Victor's unfortunate choice it was always to mis-see, to mis-hear, to misjudge. He read softness into her because of the softness of her voice, when she was only remembering. His was the self-centered chaos of childhood. All looks and thoughts, loves and hatreds, were directed at him. Softness was softness towards him, weakness was weakness in the face of his strength. He preheard answers and listened not. He was full-coloured and brilliant—all outside of him was pale.

- Act One: The Circus

- He brought his malformed wisdom, his pool-hall, locker-room, joke-book wisdom to the front.

- Act One: The Circus. "He" is Victor.

- Mordeen said: "I used to wonder why this love seemed sweeter than I had ever known, better than many people ever know. And then one day the reason came to me. There are very few great Anythings in the world. In work and art and emotion—the great is very rare. And I have one of the great and beautiful. Now say your yah, yah, Victor, like a child unanswerably answering Wisdom. You will have to do that, I think."

- Mordeen on her love for Joe Saul in Act One: The Circus

- His guard was up now and he wasn't listening; he was only angry because here was a world he could not enter and so he had to disbelieve in its existence. He fell back on the world he knew.

- Act One: The Circus. "He" is Victor.

- "I do understand. I understand that you are offered a loveliness and you vomit on it, that you have the gift of love given you such as few men have ever known and you throw on it the acid of your pride, your ugly twisted sense of importance."

- Friend Ed to Joe Saul in Act Three, Scene I: The Sea

- "It is so easy a thing to give—only great men have the courage and courtesy and, yes, the generosity to receive."

- Friend Ed to Joe Saul in Act Three, Scene I: The Sea

- "…Let us go," we said, "into the Sea of Cortez, realizing that we become forever a part of it; that our rubber boots slogging through a flat of eel-grass, that the rocks we turn over in a tide pool, make us truly and permanently a factor in the ecology of the region. We shall take something away from it, but we shall leave something too." And if we seem a small factor in a huge pattern, nevertheless it is of relative importance. We take a tiny colony of soft corals from a rock in a little water world. And that isn't terribly important to the tide pool. Fifty miles away the Japanese shrimp boats are dredging with overlapping scoops, bringing up tons of shrimps, rapidly destroying the species so that it may never come back, and with the species destroying the ecological balance of the whole region. That isn't very important in the world. And thousands of miles away the great bombs are falling and the stars are not moved thereby. None of it is important or all of it is.

- Introduction

- We sat on a crate of oranges and thought what good men most biologists are, the tenors of the scientific world — temperamental, moody, lecherous, loud-laughing, and healthy.[…] Your true biologist will sing you a song as loud and off-key as will a blacksmith, for he knows that morals are too often diagnostic of prostatitis and stomach ulcers. Sometimes he may proliferate a little too much in all directions, but he is as easy to kill as any other organism, and meanwhile he is very good company, and at least he does not confuse a low hormone productivity with moral ethics.

- Chapter 4

- Among primitives sometimes evil is escaped by never mentioning the name, as in Malaysia, where one never mentions a tiger by name for fear of calling him. Among others, as even among ourselves, the giving of a name establishes a familiarity which renders the thing impotent. It is interesting to see how some scientists and philosophers, who are an emotional and fearful group, are able to protect themselves against fear. In a modern scene, when the horizons stretch out and your philosopher is likely to fall off the world like a Dark Age mariner, he can save himself by establishing a taboo-box which he may call "mysticism" or "supernaturalism" or "radicalism." Into this box he can throw all those thoughts which frighten him and thus be safe from them.

- Chapter 8

- We are no better than the animals; in fact in a lot of ways we aren't as good.

- Chapter 9

- There is a strange duality in the human which makes for an ethical paradox. We have definitions of good qualities and of bad; not changing things, but generally considered good and bad throughout the ages and throughout the species. Of the good, we think always of wisdom, tolerance, kindliness, generosity, humility; and the qualities of cruelty, greed, self-interest, graspingness, and rapacity are universally considered undesirable. And yet in our structure of society, the so-called and considered good qualities are invariable concomitants of failure, while the bad ones are the cornerstones of success. A man — a viewing-point man — while he will love the abstract good qualities and detest the abstract bad, will nevertheless envy and admire the person who though possessing the bad qualities has succeeded economically and socially, and will hold in contempt that person whose good qualities have caused failure. When such a viewing-point man thinks of Jesus or St. Augustine or Socrates he regards them with love because they are the symbols of the good he admires, and he hates the symbols of the bad. But actually he would rather be successful than good. In an animal other than man we would replace the term “good” with “weak survival quotient” and the term “bad” with “strong survival quotient.” Thus, man in his thinking or reverie status admires the progression toward extinction, but in the unthinking stimulus which really activates him he tends toward survival. Perhaps no other animal is so torn between alternatives. Man might be described fairly adequately, if simply, as a two-legged paradox. He has never become accustomed to the tragic miracle of consciousness. Perhaps, as has been suggested, his species is not set, has not jelled, but is still in a state of becoming, bound by his physical memories to a past of struggle and survival, limited in his futures by the uneasiness of thought and consciousness.

- Chapter 11

East of Eden (1952)

edit- Eventlessness has no posts to drape duration on. From nothing to nothing is no time at all.

- Part 1, Ch. 7. i

- "Maybe that's the reason," Adam said slowly, feeling his way. "Maybe if I had loved him I would have been jealous of him. You were. Maybe-maybe love makes you suspicious and doubting. Is it true that when you love a woman you are never sure-never sure of her because you aren't sure of yourself? I can see it pretty clearly. I can see how you loved him and what it did to you. I did not love him. Maybe he loved me. He tested me and hurt me and punished me and finally he sent me out like a sacrifice, maybe to make up for something. But he did not love you, and so he had faith in you. Maybe — why, maybe it's a kind of reverse."

- Part 1, Ch. 7. iii

- What freedom men and women could have, were they not constantly tricked and trapped and enslaved and tortured by their sexuality! The only drawback in that freedom is that without it one would not be a human. One would be a monster.

- Part 1, Ch. 8. i

- Sometimes a kind of glory lights up the mind of a man. It happens to nearly everyone. You can feel it growing or preparing like a fuse burning toward dynamite. It is a feeling in the stomach, a delight of the nerves, of the forearms. The skin tastes the air, and every deep-drawn breath is sweet. Its beginning has the pleasure of a great stretching yawn; it flashes in the brain and the whole world glows outside your eyes. A man may have lived all his life in the gray, and the land and trees of him dark and somber. The events, even the important ones, may have trooped by faceless and pale. And then — the glory — so that a cricket song sweetens the ears, the smell of the earth rises chanting to his nose, and dappling light under a tree blesses his eyes. Then a man pours outward, a torrent of him, and yet he is not diminished…

- Part 2, Ch. 13. i

- Our species is the only creative species, and it has only one creative instrument, the individual mind and spirit of a man. Nothing was ever created by two men. There are no good collaborations, whether in art, in music, in poetry, in mathematics, in philosophy. Once the miracle of creation has taken place, the group can build and extend it, but the group never invents anything. The preciousness lies in the lonely mind of a man.

And now the forces marshaled around the concept of the group have declared a war of extermination on that preciousness, the mind of man. By disparagement, by starvation, by repressions, forced direction, and the stunning blows of conditioning, the free, roving mind is being pursued, roped, blunted, drugged. It is a sad suicidal course our species seems to have taken.

And this I believe: that the free, exploring mind of the individual human is the most valuable thing in the world. And this I would fight for: the freedom of the mind to take any direction it wishes, undirected. And this I must fight against: any religion, or government which limits or destroys the individual. This is what I am and what I am about. I can understand why a system built on a pattern must try to destroy the free mind, for it is the one thing which can by inspection destroy such a system. Surely I can understand this, and I hate it and I will fight against it to preserve the one thing that separates us from the uncreative beasts. If the glory can be killed, we are lost.- Part 2, Ch. 13. i

- There are no ugly questions except those clothed in condescension.

- Part 2, Ch. 15. ii

- In uncertainty I am certain that underneath their topmost layers of frailty men want to be good and want to be loved. Indeed, most of their vices are attempted short cuts to love. When a man comes to die, no matter what his talents and influence and genius, if he dies unloved his life must be a failure to him and his dying a cold horror. It seems to me that if you or I must choose between two courses of thought or action, we should remember our dying and try so to live that our death brings no pleasure to the world.

We have only one story. All novels, all poetry, are built on the never-ending contest in ourselves of good and evil. And it occurs to me that evil must constantly respawn, while good, while virtue, is immortal. Vice has always a new fresh young face, while virtue is venerable as nothing else in the world is.- Part 4, Ch. 34

- We all have that heritage, no matter what old land our fathers left. All colors and blends of Americans have somewhat the same tendencies. It's a breed — selected out by accident. And so we're overbrave and overfearful — we're kind and cruel as children. We're overfriendly and at the same time frightened of strangers. We boast and are impressed. We're oversentimental and realistic. We are mundane and materialistic — and do you know of any other nation that acts for ideals? We eat too much. We have no taste, no sense of proportion. We throw our energy about like waste. In the old lands they say of us that we go from barbarism to decadence without an intervening culture. Can it be that our critics have not the key or the language of our culture? That's what we are, Cal — all of us. You aren't very different.

- Part 4, Ch. 51. ii

Sweet Thursday (1954)

edit- Men do change, and change comes like a little wind that ruffles the curtains at dawn, and it comes like the stealthy perfume of wildflowers hidden in the grass.

- Ch. 3

- Where does discontent start? You are warm enough, but you shiver. You are fed, yet hunger gnaws you. You have been loved, but your yearning wanders in new fields. And to prod all these there’s time, the Bastard Time.

- Ch. 3

- "Woman and women is two different things," said Suzy. "Guy knows all about women, he don't know nothing about a woman."

- Ch. 17

- It is a common experience that a problem difficult at night is resolved in the morning after the committee of sleep has worked on it.

- Ch. 20

- Doc cried to no one, "Give me a little time! I want to think.[…] Everyone has something. And what has Suzy got? Absolutely nothing in the world but guts. She's taken on an atomic world with a sling-shot, and, by God, she's going to win! If she doesn't win there's no point in living any more.

"What do I mean, win?" Doc asked himself. "I know. If you are not defeated, you win"- Ch. 35

- No one knows how greatness comes to a man. It may lie in his blackness, sleeping, or it may lance into him like those driven fiery particles from outer space. These things, however, are known about greatness: need gives it life and puts it in action; it never comes without pain; it leaves a man changed, chastened, and exalted at the same time — he can never return to simplicity.

- Ch. 36

The Short Reign of Pippin IV (1957)

edit- It is a matter of disillusion to young male Americans otherwise informed, to discover that the French are a moral people — judged, that is, by American country-club standards.

- I have known many people to ask for advice but very few who wanted it and none who followed it.

- Power does not corrupt. Fear corrupts, perhaps fear of a loss of power.

- I don't anticipate trouble and so I anticipate trouble.

- It is the misfortune of men to want to do a thing well, even a thing they do not want to do at all.

- It seems to me that even though the king may know he will fail, the king must try.

- You are a good man, Sire, and a good man draws women as cheese draws mice.

- The one thing our species is helpless against is good fortune. It first puzzles, then frightens, then angers, and finally destroys us.

- The human fetus is born upside down. But it is not true that a child becomes upright after birth. Observe the feet of children and young people when they are at rest. The feet are nearly always higher than the head, No matter how hard he may try, the growing boy, and particularly girl, cannot keep the feet down. The fetal position is very strong. It takes eighteen to twenty years for the feet finally to accept the ground as their normal home. It is my hypothesis that you can judge maturity exactly by the relationship of the feet to the ground.

The Winter of Our Discontent (1961)

editPart One

edit- "I'm sorry," Ethan said. "You have taught me something — maybe three things, rabbit footling mine. Three things will never be believed — the true, the probable, and the logical. I know now where to get the money to start my fortune."

- Chapter II

- My dreams are the problems of the day stepped up to absurdity, a little like men dancing, wearing the horns and masks of animals.

- Chapter III

- It is odd how a man believes he can think better in a special place. I have such a place, have always had it, but I know it isn't thinking I do there, but feeling and experiencing and remembering. It's a safety place — everyone must have one, although I never heard a man tell of it.

- Chapter III

- They successfully combined piracy and puritanism, which aren't so unlike when you come right down to it. Both had a strong dislike for opposition and both had a roving eye for other people's property.

- Chapter III

- Sometimes it's great fun to be silly, like children playing statues and dying of laughter. And sometimes being silly breaks the even pace and lets you get a new start.

- Chapter III

- No man really knows about other human beings. The best he can do is to suppose that they are like himself.

- Chapter III

- Does anyone ever know even the outer fringe of another? What are you like in there? Mary — do you hear? Who are you in there?

- Chapter III

- When two people meet, each one is changed by the other so you've got two new people. Maybe that means — hell, it's complicated.

- Chapter IV

- A man who tells secrets or stories must think of who is hearing or reading, for a story has as many versions as it has readers.

- Chapter V

- I guess we're all, or most of us, the wards of that nineteenth-century science which denied existence to anything it could not measure or explain. The things we couldn't explain went right on but surely not with our blessing. We did not see what we couldn't explain, and meanwhile a great part of the world was abandoned to children, insane people, fools, and mystics, who were more interested in what is than in why it is. So many old and lovely things are stored in the world's attic, because we don't want them around us and we don't dare throw them out.

- Chapter V

- What a wonderful thing a woman is. I can admire what they do even if I don't understand why.

- Chapter V

- Even if teen-age children aren't making a sound, it's quieter when they're gone. They put a boiling in the air around them. As they left, the whole house seemed to sigh and settle. No wonder poltergeists infest only houses with adolescent children.

- Chapter V

- What a frightening thing is the human, a mass of gauges and dials and registers, and we can read only a few and those perhaps not accurately.

- Chapter V

- A little hope, even hopeless hope, never hurt anybody.

- Chapter V

- Can you disbelieve in something you don't know about? […] It isn't that I don't believe but that I don't know.

- Chapter V

- To be alive at all is to have scars.

- Chapter VI

- No one wants advice — only corroboration.

- Chapter VI

- "Ellen, only last night, asked, 'Daddy, when will we be rich?' But I did not say to her what I know: 'We will be rich soon, and you who handle poverty badly will handle riches equally badly.' And that is true. In poverty she is envious. In riches she may be a snob. Money does not change the sickness, only the symptoms."

- Chapter VII

- In the dusk I saw her smile, that incredible female smile. It is called wisdom but it isn't that but rather an understanding that makes wisdom unnecessary.

- Chapter VII

- The misery stayed, not thought about but aching away, and sometimes I would have to ask myself, Why do I ache? Men can get used to anything, but it takes time.

- Chapter VIII

- There's something desirable about anything you're used to as opposed to something you're not.

- Chapter VIII

- You know how advice is. You only want it if it agrees with what you wanted to do anyway.

- Chapter IX

Part Two

edit- All men are moral. Only their neighbors are not.

- Chapter XI

- A man is a lonely thing.

- Chapter XI

- Maybe not having time to think is not having the wish to think.

- Chapter XIII

- Strength and success— they are above morality, above criticism. It seems then, that it is not what you do, but how you do it and what you call it.

- Chapter XIII

- Not only the brave get killed, but the brave have a better chance of it.

- Chapter XIV

- Good God, what a mess of draggle-tail impulses a man is — and a woman too, I guess.

- Chapter XIV

- … we've got so many laws you can't breathe without breaking something.

- Chapter XIV

- The things everyone knows are most likely to be wrong.

- Chapter XIX

- Like most modern people, I don't believe in prophecy or magic and then spend half my time practicing it.

- Chapter XIX

- A crime is something someone else commits.

- Chapter XX

- A secret's a terribly lonesome thing.

- Chapter XXI

- There's nobody as lonely as an all-married man.

- Chapter XXI

Nobel Prize acceptance speech (1962)

edit- Speech at the Nobel Banquet (10 December 1962) (with links to audio file)

- In my heart there may be doubt that I deserve the Nobel award over other men of letters whom I hold in respect and reverence — but there is no question of my pleasure and pride in having it for myself.

It is customary for the recipient of this award to offer personal or scholarly comment on the nature and the direction of literature. At this particular time, however, I think it would be well to consider the high duties and the responsibilities of the makers of literature.

- Such is the prestige of the Nobel award and of this place where I stand that I am impelled, not to squeak like a grateful and apologetic mouse, but to roar like a lion out of pride in my profession and in the great and good men who have practiced it through the ages.

- Literature was not promulgated by a pale and emasculated critical priesthood singing their litanies in empty churches — nor is it a game for the cloistered elect, the tinhorn mendicants of low calorie despair.

Literature is as old as speech. It grew out of human need for it, and it has not changed except to become more needed.

The skalds, the bards, the writers are not separate and exclusive. From the beginning, their functions, their duties, their responsibilities have been decreed by our species.

- Humanity has been passing through a gray and desolate time of confusion. My great predecessor, William Faulkner, speaking here, referred to it as a tragedy of universal fear so long sustained that there were no longer problems of the spirit, so that only the human heart in conflict with itself seemed worth writing about.

Faulkner, more than most men, was aware of human strength as well as of human weakness. He knew that the understanding and the resolution of fear are a large part of the writer's reason for being.

This is not new. The ancient commission of the writer has not changed. He is charged with exposing our many grievous faults and failures, with dredging up to the light our dark and dangerous dreams for the purpose of improvement.

- The writer is delegated to declare and to celebrate man's proven capacity for greatness of heart and spirit — for gallantry in defeat — for courage, compassion and love. In the endless war against weakness and despair, these are the bright rally-flags of hope and of emulation.

I hold that a writer who does not passionately believe in the perfectibility of man, has no dedication nor any membership in literature.

- With humanity's long proud history of standing firm against natural enemies, sometimes in the face of almost certain defeat and extinction, we would be cowardly and stupid to leave the field on the eve of our greatest potential victory.

- We have usurped many of the powers we once ascribed to God.

Fearful and unprepared, we have assumed lordship over the life or death of the whole world — of all living things.

The danger and the glory and the choice rest finally in man. The test of his perfectibility is at hand.

Having taken Godlike power, we must seek in ourselves for the responsibility and the wisdom we once prayed some deity might have.

Man himself has become our greatest hazard and our only hope.

So that today, St. John the apostle may well be paraphrased: In the end is the Word, and the Word is Man — and the Word is with Men.

- A journey is like marriage. The certain way to be wrong is to think you control it.

- Pt. 1

- When I was very young and the urge to be someplace was on me, I was assured by mature people that maturity would cure this itch. When years described me as mature, the remedy prescribed was middle age. In middle age I was assured that greater age would calm my fever and now that I am fifty-eight perhaps senility will do the job. Nothing has worked… In other words, I don’t improve, in further words, once a bum always a bum. I fear the disease is incurable.

- Pt. 1

- A kind of second childhood falls on so many men. They trade their violence for the promise of a small increase of life span. In effect, the head of the house becomes the youngest child. And I have searched myself for this possibility with a kind of horror. For I have always lived violently, drunk hugely, eaten too much or not at all, slept around the clock or missed two nights of sleeping, worked too hard and too long in glory, or slobbed for a time in utter laziness. I’ve lifted, pulled, chopped, climbed, made love with joy and taken my hangovers as a consequence, not as a punishment. I did not want to surrender fierceness for a small gain in yardage. My wife married a man; I saw no reason why she should inherit a baby.

- Pt. 1

- Four hoarse blasts of a ship’s whistle still raise the hair on my neck and set my feet to tapping.

- Pt. 1

- The sound of a jet, an engine warming up, even the clopping of shod hooves on pavement brings on the ancient shudder, the dry mouth and vacant eye, the hot palms and the churn of stomach high up under the rib cage.

- Pt. 1

- The techniques of opening conversation are universal. I knew long ago and rediscovered that the best way to attract attention, help, and conversation is to be lost. A man who seeing his mother starving to death on a path kicks her in the stomach to clear the way, will cheerfully devote several hours of his time giving wrong directions to a total stranger who claims to be lost.

- Pt. 1

- When the virus of restlessness begins to take possession of a wayward man, and the road away from Here seems broad and straight and sweet, the victim must first find himself a good and sufficient reason for going.

- Pt. 1

- And now, our submarines are armed with mass murder, our silly, only way of deterring mass murder.

- Pt. 1

- Oh, we can populate the dark with horrors, even we who think ourselves informed and sure, believing nothing we cannot measure or weigh. I know beyond all doubt that the dark things crowding in on me either did not exist or were not dangerous to me, and still I was afraid.

- Pt. 1

- The mountains of things we throw away are much greater than the things we use. In this, if in no other way, we can see the wild and reckless exuberance of our production, and waste seems to be the index.

- Pt. 2

- The new American finds his challenge and his love in the traffic-choked streets, skies nested in smog, choking with the acids of industry, the screech of rubber and houses leashed in against one another while the townlets wither a time and die. This is not offered in criticism but only as observation. And I am sure that, as all pendulums reverse their swing, so eventually will the swollen cities rupture like dehiscent wombs and disperse their children back to the countryside.

- Pt. 2

- Even while I protest the assembly-line production of our food, our songs, our language, and eventually our souls, I know that it was a rare home that baked good bread in the old days. Mother’s cooking was with rare exceptions poor, that good unpasteurized milk touched only by flies and bits of manure crawled with bacteria, the healthy old-time life was riddled with aches, sudden death from unknown causes, and that sweet local speech I mourn was the child of illiteracy and ignorance. It is the nature of a man as he grows older, a small bridge in time, to protest against change, particularly change for the better.

- Pt. 2

- I am in love with Montana. For other states I have admiration, respect, recognition, even some affection, but with Montana it is love.

- Pt. 2

- I guess this is why I hate governments. It is always the rule, the fine print, carried out by the fine print men. There's nothing to fight, no wall to hammer with frustrated fists.

- Pt. 2

- This monster of a land, this mightiest of nations, this spawn of the future, turns out to be the macrocosm of microcosm me.

- Pt. 3

- The Mojave is a big desert and a frightening one. It’s as though nature tested a man for endurance and constancy to prove whether he was good enough to get to California.

- Pt. 3

- There used to be a thing or a commodity we put great store by. It was called the People. Find out where the People have gone. I don’t mean the square-eyed toothpaste-and-hair-dye people or the new-car-or-bust people, or the success-and-coronary people. Maybe they never existed, but if there ever were the People, that’s the commodity the Declaration was talking about, and Mr. Lincoln.

- Pt. 3

- He wasn't involved with a race that could build a thing it had to escape from.

- Pt. 3

- I wonder why progress looks so much like destruction.

- Pt. 3

- We value virtue but do not discuss it. The honest bookkeeper, the faithful wife, the earnest scholar get little of our attention compared to the embezzler, the tramp, the cheat.

- Pt. 3

- Life could not change the sun or water the desert, so it changed itself.

- Pt. 3

- Texas is a state of mind. Texas is an obsession. Above all, Texas is a nation in every sense of the word. And there’s an opening covey of generalities. A Texan outside of Texas is a foreigner.

- Pt. 4

- Sectional football games have the glory and the despair of war, and when a Texas team takes the field against a foreign state, it is an army with banners.

- Pt. 4

- A question is a trap, and an answer your foot in it.

- Pt. 4

- He doesn't belong to a race clever enough to split the atom but not clever enough to live at peace with itself.

- Pt. 4

Paris Review - The Art of Fiction No. 45 (1969)

edit- For a while I was a vicious fighter but it wasn't to win. It was to get it over and get the hell out of there. And I never would have done it at all if other people hadn't put me in the ring. The only private fights I ever had were those I couldn't get away from.

- I have never even wondered about the comparative standing of writers. I don't understand that. Writing to me is a deeply personal, even a secret function and when the product is turned loose it is cut off from me and I have no sense of its being mine. Consequently criticism doesn't mean anything to me. As a disciplinary matter, it is too late.

- I can remember the horror which came over my parents when they became convinced that it was so with me [that I wanted to be a writer]—and properly so. What you have and they had to look forward to is life made intolerable by a mean, cantankerous, opinionated, moody, quarrelsome, unreasonable, nervous, flighty, irresponsible son. You will get no loyalty, little consideration and desperately little attention from him. In fact you will want to kill him. I'm sure my father and mother often must have considered poisoning me.

Journal of a Novel (1969)

edit- A "work diary" kept by Steinbeck during the writing of the first draft of East of Eden in 1951

- In utter loneliness a writer tries to explain the inexplicable. And sometimes if he is very fortunate and if the time is right, a very little of what he is trying to do trickles through — not ever much. And if he is a writer wise enough to know it can't be done, then he is not a writer at all. A good writer always works at the impossible.

- January 29, 1951

- I like a chapter to have design of tone, as well as of form. A chapter should be a perfect cell in the whole book and should be almost able to stand alone. If this is done then the breaks we call chapters are not arbitrary but rather articulations which allow the free movement of the story.

- March 7, 1951

- I am glad that I can use the oldest story in the world to be the design of the newest story for me. The lack of change in the world is the thing which astonishes me.[…] And now I had set down in my own hand the 16 verses of Cain and Abel and the story changes with flashing lights when you write it down. And I think I have a title at last, a beautiful title, EAST OF EDEN. And read the 16th verse to find it. And the Salinas Valley is surely East Of Eden.[…] And […] as I went into the story more deeply I began to realize that without this story — or rather a sense of it — psychiatrists would have nothing to do. In other words this one story is the basis of all human neurosis — and if you take the fall along with it, you have the total of the psychic troubles which can happen to a human.

- June 11, 1951

- I believe that the great ones, Plato, Lao Tze, Buddha, Christ, Paul and the great Hebrew prophets are not remembered for negation or denial. Not that it is necessary to be remembered but there is one purpose in writing that I can see, beyond simply doing it interestingly. It is the duty of the writer to lift up, to extend, to encourage. If the written word has contributed anything at all to our developing species and our half developed culture, it is this: Great writing has been a staff to lean on, a mother to consult, a wisdom to pick up stumbling folly, a strength in weakness and a courage to support sick cowardice. And how any negative or despairing approach can pretend to be literature I do not know. It is true that we are weak and sick and ugly and quarrelsome but if that is all we ever were, we would milleniums ago have disappeared from the face of the earth, and a few remnants of fossilized jaw bones, a few teeth in strata of limestone would be the only mark our species would have left on the earth.

- June 28, 1951

- … the writer must believe that what he is doing is the most important thing in the world. And he must hold to this illusion even when he knows it is not true.

- September 3, 1951

- I have noticed so many of the reviews of my work show a fear and hatred of ideas and speculations. It seems to be true that people can only take parables fully clothed with flesh. Any attempt to correlate in terms of thought is frightening. And if that is so, East of Eden is going to take a bad beating because it is full of such things.

- October 10, 1951

- A book is like a man — clever and dull, brave and cowardly, beautiful and ugly. For every flowering thought there will be a page like a wet and mangy mongrel, and for every looping flight a tap on the wing and a reminder that wax cannot hold the feathers firm too near the sun.

- From a letter to Pascal Covici (1952)

- Some people there are who, being grown, forget the horrible task of learning to read. It is perhaps the greatest single effort that the human undertakes, and he must do it as a child. An adult is rarely successful in the undertaking — the reduction of experience to a set of symbols. For a thousand thousand years these humans have existed and they have only learned this trick — this magic — in the final ten thousand of the thousand thousand.

- Introduction

- In the combat between wisdom and feeling, wisdom never wins.

- Merlin to King Arthur in "The Death of Merlin"

- This is the law. The purpose of fighting is to win. There is no possible victory in defense. The sword is more important than the shield, and skill is more important than either. The final weapon is the brain, all else is supplementary.

- "If lowborn men could stand up to those born to rule, religion, government, the whole world would fall to pieces."

"So it would," she said. "So it will."

"I don't believe you," Ewain said. "But for the sake of the discussion, what then, my lady?"

"Why then — then the pieces would have to be put together again."

"By such as these—?"

"Who else? Who indeed else?"- Sir Ewain and Lady Lyne envisaging the demise of knighthood at the hands of the lowborn in "Gawain, Ewain, and Marhalt"

- One of the greatest errors in the reconstruction of another era lies in our tendency to think of them as being like ourselves in feeling and attitudes. Actually, without considerable study on the part of a present-day man — if he were confronted by a fifteenth-century man — there would be no possible communication. I think it is possible through knowledge and discipline for a modern man to understand, and, to a certain extent, live into a fifteenth-century mind, but the reverse would be completely impossible.

- Appendix, letter to Elizabeth Otis and Chase Horton (14 March 1958)

- An artist should be open on all sides to every kind of light and darkness.

- Appendix, letter to Elizabeth Otis and Chase Horton (20 April 1959)

- Writers are a sorry lot. The best you can say of them is that they are better than actors and that's not much.

- Appendix, letter to Chase Horton (8 June 1959)

- Now back to Malory.[…] As I go along, I am constantly jiggled by the arrant nonsense of a great deal of the material. A great deal of it makes no sense at all. Two thirds of it is the vain dreaming of children talking in the dark. And then when you are about to throw it out in disgust, you remember the Congressional Record or the Sacco and Vanzetti case or 'preventive war' or our national political platforms, or racial problems that can't be settled reasonably or domestic relations, or beatniks, and it is borne in on you that the world operates on nonsense — that it is a large part of the pattern and that knight errantry is no more crazy than our present-day group thinking, and activity. That is the way humans are. If you inspected them and their activities in the glass of reason, you would drown the whole lot.

- Appendix, letter to Chase Horton (8 June 1959)

- I can tell you one thing I have finally faced through — the Arthurian cycle and practically all lasting and deep-seated folklore is a mixture of profundity and childish nonsense. If you keep the profundity and throw out the nonsense, some essence is lost. These are dream stories, fixed and universal dreams, and they have the inconsistency of dreams.

- Appendix, letter to Elizabeth Otis (June 1959)

- Most people live in a half-dream all their lives and call it reality.

- Appendix, letter to Elizabeth Otis (25 July 1959)

- [On writing:] It is properly called the lonesomest profession in the world.

- Appendix, letter to Elizabeth Otis (22 August 1959)

Writers at Work (1977)

edit- Fourth Series, edited by George Plimpton

- Give a critic an inch, he’ll write a play.

- On Critics

- Time is the only critic without ambition.

- On Critics

- I have owed you this letter for a very long time — but my fingers have avoided the pencil as though it were an old and poisoned tool.

- Letter to his literary agent, found on his desk after his death in 1968

Disputed

edit- Socialism never took root in America because the poor see themselves not as an exploited proletariat, but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires.

- As quoted in A Short History of Progress (2004) by Ronald Wright: "John Steinbeck once said that socialism never took root in America because the poor see themselves not as an exploited proletariat but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires." This has since been cited as a direct quote by some, but the remark is very likely a paraphrase from Steinbeck's article "A Primer on the '30s." Esquire (June 1960), p. 85-93:

- "Except for the field organizers of strikes, who were pretty tough monkeys and devoted, most of the so-called Communists I met were middle-class, middle-aged people playing a game of dreams. I remember a woman in easy circumstances saying to another even more affluent: 'After the revolution even we will have more, won't we, dear?' Then there was another lover of proletarians who used to raise hell with Sunday picknickers on her property.

- "I guess the trouble was that we didn't have any self-admitted proletarians. Everyone was a temporarily embarrassed capitalist. Maybe the Communists so closely questioned by the investigation committees were a danger to America, but the ones I knew — at least they claimed to be Communists — couldn't have disrupted a Sunday-school picnic. Besides they were too busy fighting among themselves."

Quotes about Steinbeck

edit- I can't read ten pages of Steinbeck without throwing up. I couldn't read the proletarian crap that came out in the '30s; again you had sentimentalism — the poor oppressed workers.

- James Gould Cozzens, "Books: The Hermit of Lambertville", Time (2 September 1957)

- Steinbeck's novel The Grapes of Wrath and the subsequent John Ford movie promulgated a populist mythology about depression-era migrants to California who were dubbed "Okies," no matter what southwestern or midwestern state they hailed from. But most Californians regarded Okies as dirty, shifty, lazy, violent, and ignorant.

- Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz Outlaw Woman (2001)

- There was one New Deal agency that proved helpful to us in the fields, and that was the Farm Security Administration. The FSA administered a system of migrant labor camps in California. When I read about the Joads arriving at the temporary safe haven of the "government camp" in The Grapes of Wrath, I knew exactly what they felt like.

- Dorothy Ray Healey California Red: A Life in the American Communist Party (1990)

- I read Cannery Row very carefully. I wanted to see how he did some things. At the end of Cannery Row there is a party and somebody recites a poem and it doesn't stop the dramatic action. I studied how he did that because I wanted to quote some songs and poems without stopping the drama.

- 1980 interview in Conversations with Maxine Hong Kingston (1998)

- Steinbeck is extremely angry about the fact that the common man who is striving very hard, who wants so very little, is not even able to attain that little if it backs up against the interests of the banks and of the big landowners. You know, and that’s what The Grapes of Wrath, I think, is basically about, is about watching these people try to simply live who asking for little. They are not angry people. They are not revolutionaries. They are not sophisticated. They they simply want to farm a tenant farmers. They simply want to go out but their butts every day and get a small return and then pass that on to their children. And even that under certain circumstances is asking too much if you’re going to inopportune the banking interest. And that’s what made Steinbeck so furious...what he’s saying is that people it’s just not fair. That’s what he’s saying...he believes it is at this point that even people like the Joads can be moved to anger at the just at just the epitome of the unfairness of it all.

- Gloria Naylor Interview with PBS (2000)

- The change in character of the workers in Southern California's garment industry struck me forcibly. Mexican women and girls were no longer in the majority, although some of the younger generation were still favored in certain factories. The working force in this region had been vastly augmented since 1936, because of the changing trends, and the manufacturers had taken on a great number of women from newly migrant families, largely American-born whites and Negroes, former tenant farmers who had gravitated to California from burned-out and wind-torn land East of the Rockies. Generally referred to as Dust-Bowlers, and made famous as Ma Joads through John Steinbeck's Grapes of Wrath, they had no conception of the meaning of unionism. Some had long been on county relief and WPA, with meager rations and were glad to work for any wage and to put in any number of hours.

- Rose Pesotta Bread Upon the Waters (1987)

- John Steinbeck/would sharpen/twenty-four pencils every day/and write/till they were/dull.

- Naomi Shihab Nye Voices in the Air (2018)

- When one thinks of California agriculture during the Depression, John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath generally comes to mind. Steinbeck did not exaggerate. White and African American Dust Bowl migrants alongside Mexicanos and Filipinos endured great hardships.

- Vicki L. Ruiz, From Out of the Shadows: Mexican Women in Twentieth-Century America

External links

edit- Encyclopedic article on John Steinbeck on Wikipedia

- Media related to John Steinbeck on Wikimedia Commons

- Nobel Laureate page

- 1989 Audio Interview with Robert Demott talking to Don Swaim about John Steinbeck, RealAudio

- 1989 Audio Interview with Elaine Steinbeck talking to Don Swaim about John Steinbeck, RealAudio

- Of Mice and Men quotes analyzed; study guide with themes, character analyses, summary, teaching guide

- The Grapes of Wrath quotes analyzed