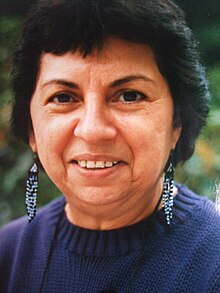

Gloria E. Anzaldúa

Chicana cultural theory, feminist theory, and queer theory (1942-2004)

Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa (September 26, 1942 – May 15, 2004) was a Chicana lesbian feminist scholar of Chicana cultural theory, feminist theory, and queer theory. She loosely based her best-known book, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, on her life growing up on the Mexico–Texas border and incorporated her lifelong experiences of social and cultural marginalization into her work.

Quotes

edit- Bridges are thresholds to other realities, archetypal, primal symbols of shifting consciousness. They are passageways, conduits, and connectors that connote transitioning, crossing borders, and changing perspectives. Bridges span liminal (threshold) spaces between worlds, spaces I call nepantla, a Nahuatl word meaning tierra entre medio. Transformations occur in this in-between space, an unstable, unpredictable, precarious, always-in-transition space lacking clear boundaries. Nepantla es tierra desconocida, and living in this liminal zone means being in a constant state of displacement--an uncomfortable, even alarming feeling. Most of us dwell in nepantla so much of the time it’s become a sort of “home.” Though this state links us to other ideas, people, and worlds, we feel threatened by these new connections and the change they engender.

- "(Un)natural Bridges, (Un)safe Spaces" from This Bridge We Call Home: Radical Visions for Transformation (2002), p. 1

- The Chicano Movement coalesced identity and I have a lot of respect for it despite its sexist attitudes. For that reason it started diminishing. It's not dead, but the male aspect of it is diminishing because the men would not confront thing but racial issues. The movement to me is now like a mosaic with all these little pieces. The little pieces are the ones that are now being activated so that a poet like Lorna Dee Cervantes is her own little miniature movement. Francisco Alarcón, Norma Alarcón, José Limón, all the people who are writing are carrying out the struggle against domination and subordination in the kinds of things they focus on-language, folklore, just anything.

- 1990 interview in Conversations with Contemporary Chicana and Chicano Writers edited by Hector A. Torres (2007)

- The soul uses everything to further its own making. … States which disrupt the smooth flow (complacency) of life are exactly what propel the soul to do its work: make soul, increase consciousness of itself. Our greatest disappointments and painful experiences—if we can make meaning out of them—can lead us toward becoming more of who we are.

- p. 68

- At some point, on our way to a new consciousness, we will have to leave the opposite bank, the split between the two mortal combatants somehow healed so that we are on both shores at once and, at once, see through serpent and eagle eyes. Or perhaps we will decide to disengage from the dominant culture, write it off all together as a lost cause, and cross the border into a wholly new and separate territory. Or we might go another route. The possibilities are numerous once we decide to act and not react.

- "La Conciencia de la Mestiza: Towards a New Consciousness," p. 100

- That focal point or fulcrum, that juncture where the mestiza stands, is where phenomena tend to collide. It is where the possibility of uniting all that is separate occurs. This assembly is not one where severed or separated pieces merely come together. Nor is it a balancing of opposing powers. In attempting to work out a synthesis, the self has added a third element which is greater than the sum of its severed parts. That third element is a new consciousness—a mestiza consciousness.

- p. 102

- They'd like to think I have melted in the pot. But I haven't. We haven't.

- p. 108

- A misinformed people is a subjugated people.

- p. 108

- I did participate in the Chicano Movement. Actually, I started out with MECHA, a Mexican American youth organization. Also I was involved with different farm worker activities in South Texas and later in Indiana. When I became more recognized as a writer, I started articulating a lot of these feminist ideas that were a kind of continuation of the Chicano Movement. But I call it "El Movimiento Macha." A marimacha is a woman who is very assertive. That is what they used to call dykes, marimachas, half-and-halfs. You were different, you were queer, not normal, you were marimacha. I had been witnessing all these Chicana writers, activists, artists and professors who were very strong and therefore very marimacha. So I named it "El Movimiento Macha" as the Chicano Civil Rights Movement kind of petered out. And there were women like myself, many Chicanas, who were already questioning, having problems with the guys who were ignoring women's issues. Therefore, in the eighties and nineties, there are all these women-Chicana activists, writers and artists-around, and I listen to them, read them and reflect their influence on my life as well. What you could say is that in the sixties and the early seventies the Chicanos were at the controls. They were the ones who were visible, the Chicano leaders. Then in the eighties and nineties, the women have become visible. I see a lot of Chicanas when I travel. They come up to me, and while we are talking I ask them about their role models. They mention names like Cherríe Moraga, Gloria Anzaldúa and other Chicana authors. It is, and will continue to be, women that they are reading, that they respect. Not the guys. So it-the Chicano Movement-has shifted into the Movimiento Macha.

- when Chicanas read Borderlands, when it was read by little Chicanas in particular, it somehow legitimated them. They saw that I was code-switching, which is what a lot of Chicanas were doing in real life as well, and for the first time after reading that book they seemed to realize, "Oh, my way of writing and speaking is okay" and, "Oh, she is writing about La Virgen de Guadalupe, about la Llorona, about the corridos, the gringos, the abusive, et cetera. So if she [Gloria Anzaldúa] does it, why not me as well?" The book gave them permission to do the same thing. So they started using code-switching and writing about all the issues they have to deal with in daily life. To them, it was like somebody was saying: You are just as important as a woman as anybody from another race. And the experiences that you have are worth being told and written about.

- My whole struggle is to change the disciplines, to change the genres, to change how people look at a poem, at theory or at children's books. So I have to struggle between how many of these rules I can break and how I still can have readers read the book without getting frustrated.

- more and more people today become border people because the pace of society has increased. Just think about multi-media, computers and World Wide Web, for example. By the Internet you can communicate instantly with someone in India or somewhere else in the world, like Australia, Hungary or China. We are all living in a society where these borders are transgressed constantly.

- I also want Chicano kids to hear stuff about la Llorona, about the border, et cetera, as early as possible. I don't want them to wait until they are eighteen or nineteen to get that information. I think it is very important that they get to know their culture already as children. Here in California I met a lot of young Chicanos and Chicanas who didn't have a clue about their own Chicano culture. They lost it all. However, later on, when they were already twenty, twenty-five or even thirty years old, they took classes in Chicano studies to learn more about their ancestors, their history and culture. But I want the kids to already have access to this kind of information. That is why I started writing children's books. So far I have had two bilingual books published, and I am writing the third one at the moment. This is going to be more for juvenile readers, little boys and girls who are like ages eleven to twelve. Next I want to write a book for young adults who are about fifteen to sixteen years old as well. With my children's books I want to provide them with more knowledge about their roots and, by doing so, give them the chance to choose. To choose whether they want to be completely assimilated, whether they want to be border people, or whether they want to be isolationists.

- I am a seventh generation American and so I don't have any 'real Mexican' roots. So this is what happened to someone living at the border like me: My ancestors have always lived with the land here in Texas. My indigenous ancestors go back twenty to twenty-five thousand years and that is how old I am in this country. My Spanish ancestors have been in this land since the European takeover which pulled migration from Spain to Mexico. Texas was part of a Mexican state called Tamaulipas. And Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and part of California and Colorado, were part of the northern section of Mexico. It was almost half of Mexico that the U.S. cheated Mexico out of when they bought it by the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. By doing so they created the borderlands. The Anzaldúas lived right at the border. Therefore the ones of our family who ended up north of the border, in the U.S., were the Anzaldúas with an accent, whereas the ones that still lived in Mexico dropped their accent after a while. As the generations then went by, we lost contact with each other. Nowadays the Anzaldúas in the United States no longer know the Anzalduas in Mexico. The border split my family, so to speak.

- the feeling of not belonging to any culture at all, of being an exile in all the different cultures. You feel like there are all these gaps, these cracks in the world. In that case I would draw a crack in the world. Then I start thinking: "Okay, what does this say about my gender, my race, the discipline of writing, the U.S. society in general and finally about the whole world?" And I start seeing all these cracks, these things that don't fit. People pass as though they were average or normal; however, everybody is different. There is no such thing as normal or average. And your culture says: "That is reality!" Women are this way, men are this way, white people are this way. And you start seeing behind that reality. You see the cracks and realize that there are other realities. Women can be this or that, whites can be this or that. Besides physical reality there might be a spiritual reality. A parallel world, a world of the supernatural. After having realized all these cracks, I start articulating them and I do this particularly in the theory. I have stories where these women, these prietas-they are all prietas-actually have access to other worlds through these cracks. So I take these major things, I just go with it and work it out as much as I can. I bring the concept of borders and borderlands more into unraveling all that, too. And I now call it Nepantla, which is a Nahuatl word for the space between two bodies of water, the space between two worlds. It is a limited space, a space where you are not this or that but where you are changing. You haven't got into the new identity yet and haven't left the old identity behind either-you are in a kind of transition. And that is what Nepantla stands for. It is very awkward, uncomfortable and frustrating to be in that Nepantla because you are in the midst of transformation.

- gender is an important issue, too, as in most of the major religions in the world-like Christianity, Hindi and Islam-women are second-place and inferior. Women are regarded as nothing and often treated worse than cattle. In all these religions there is that attitude underneath. But yes, Christianity has cleaned up a lot of that. However, if you look at all the violence towards women, women are battered, molested, raped or killed-for example, one out of every three women in this country gets molested-there is a deep hatred and fear of women. So, yeah, the white culture emphasizes that we are all equal, men and women. However, underneath all that there is this violence against women, all this negative stuff about women. So if you can see through that illusion, through those cracks, you can see to that reality-of Protestantism, Christianity, Judaism, Hindi, Islam and Moslem, the major religions in the world-that they still have that negative attitude towards women as they continue to regard and treat them as inferior beings.

- When you go through a heavy difficult time, and you don't have the resources, you can't go to anybody in the society or in the community, you finally fall back on yourself. What I did was that I started breathing. I had to like breathing and to start meditating in order to get through the pain and that whole difficult period. And all that reconnected me with nature, from which I had gotten away. So this is why I like to live at the ocean, like I do now here in Santa Cruz. You know, to live near the ocean means that you just go there and then get another infusion of energy. All the petty problems you have fall away because of the presence of the ocean. It therefore is a real spiritual presence for me. I feel that way with some trees, the wind, serpents, snakes, deserts, too. So in the periods that I was going through, my very darkest times when there was nobody there for me, I realized that at least I had to be there for me.

- An addiction (a repetitious act) is a ritual to help one through a trying time; its repetition safeguards the passage, it becomes one's talisman, one's touchstone. If it sticks around after having outlived its usefulness, we become "stuck" in it and it takes possession of us. But we need to be arrested. Some past experience or condition has created this need. This stopping is a survival mechanism, but one which must vanish when it's no longer needed if growth is to occur.

- Wild tongues can't be tamed, they can only be cut out.

- Like all people, we perceive the version of reality that our culture communicates. Like others having or living in more than one culture, we get multiple, often opposing messages. The coming together of two self-consistent but habitually incomparable frames of reference causes un choque, a cultural collision.

- Who is to say that robbing a people of its language is less violent than war?

- The answer to the problem between the white race and the colored, between males and females, lies in healing the split that originates in the very foundation of our lives, our culture, our languages, our thoughts. A massive uprooting of dualistic thinking in the individual and collective consciousness is the beginning of a long struggle, but one that could in our best hopes, bring us to the end of rape, of violence, of war.

- I preferred the world of imagination to the death of sleep

- only through the body, through the pulling of flesh, can the human soul be transformed. And for images, words, stories to have this transformative power, they must arise from the human body--flesh and bone--and from the Earth's body--stone, sky, liquid, soil.

- Borders are set up to define the places that are safe and unsafe, to distinguish us from them. A border is a dividing line, a narrow strip along a steep edge. A borderland is a vague and undetermined place created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary. It is in a constant state of transition. The prohibited and forbidden are its inhabitants.

- Those who are pushed out of the tribe for being different are likely to become more sensitized (when not brutalized into insensitivity).

- Alienated from her mother culture, ‘alien' in the dominant culture, the woman of color does not feel safe within the inner life of her Self. Petrified, she can’t respond, her face caught between los intersticios, the spaces between the different worlds she inhabits.

- There is something compelling about being both male and female, about having an entry into both worlds. Contrary to some psychiatric tenets, half and halfs are not suffering from a confusion of sexual identity, or even from a confusion of gender. What we are suffering from is an absolute despot duality that says we are able to be only one or the other. It claims that human nature is limited and cannot evolve into something better. But I, like other queer people, am two in one body, both male and female. I am the embodiment of the hieros gamos: the comig together of opposit qualities within.

- the skin of the earth is seamless. The sea cannot be fenced, El mar does not stop at borders

Interview (1993)

editin Backtalk: women writers speak out by Donna Marie Perry

- (Q: Did people in your family tell stories about their own lives?) A: Some of the stories had to do with animals. My father told about black ghost dogs, espantos, and Mamágrande Ramona told rabid coyote stories and stories of Pancho Villa coming across the border and raiding the pueblos.

- When everybody says "lesbian," a word connected with Sappho and the island of Lesbos, that automatically means that your forefathers and foremothers are European, that George Washington is the father of our country and Columbus discovered America-all false assumptions.

- I'm using the word nos/otras. Otras means other and nos means us, we. We don't have to keep using the oppositional language of the fathers. We were taught to write and think like these theorists. It's complicitous for somebody who is an "other" to be using "their" terms and "their" styles all the time. It's like fighting them with their own language. Audre Lorde said it very succinctly: "You cannot use the master's tools to dismantle the master's house.

- the lesbian community is under siege, we always try to present to the heterosexual community the idealized version, but I do not think that's a good way to do it, even though I can understand where it's coming from. ("Valerie Miner talked about the kinds of self-censorship she finds in her work when she starts thinking she should present only positive images of lesbians or working-class people.") Yes. In that poem and also in the poem "Night Voice" I do that. There's this whole controversy now over media images of lesbians and gays and bisexuals. It's brought out in movies like Basic Instinct and Silence of the Lambs where they are presented as killers. It comes up in the novels of P. D. James, where she has these criminals who are lesbians or gay men. And I hate that. But, at the same time, I want the dirty laundry to be out there, whether it's on the Mexican culture or the lesbian culture or the bisexual. And I'm not sure how you do that.

- Gloria E. Anzaldúa interview in Backtalk: women writers speak out by Donna Marie Perry (1993)

- Why am I compelled to write? Because the writing saves me from this complacency I fear. Because I have no choice. Because I must keep the spirit of my revolt and myself alive. Because the world I create in the writing compensates for what the real world does not give me. By writing I put order in the world, give it a handle so I can grasp it. I write because life does not appease my appetites and hunger. I write to record what others erase when I speak, to rewrite the stories others have miswritten about me, about you.

- in The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader (2009), p. 30

- Many have a way with words. They label themselves seers but they will not see. Many have the gift of tongue but nothing to say. Do not listen to them. Many who have words and tongue have no ear, they cannot listen and they will not hear. (p. 171)

- Write with your eyes like painters, with your ears like musicians, with your feet like dancers. You are the truthsayer with quill and torch. Write with your tongues of fire. Don't let the pen banish you from yourself. (p. 171)

- We are not reconciled to the oppressors who whet their howl on our grief. We are not reconciled. (p. 171)

1983 Forward to 2nd edition

edit- Perhaps like me you are tired of suffering and talking about suffering, estás hasta el pescuezo de sufrimiento, de contar las lluvias de sangre pero no las lluvias de flores (up to your neck with suffering, of counting the rainsof blood but not the rains of flowers).

- Basta de gritar contra el viento-toda palabra es ruido si no está acompañada de acción (enough of shouting against the wind-all words are noise if not accompanied with action).

- We have come to realize that we are not alone in our struggles nor separate nor autonomous but that we-white black straight queer female male-are connected and interdependent. We are each accountable for what is happening down the street, south of the border or across the sea. And those of us who have more of anything: brains, physical strength, political power, spiritual energies, are learning to share them with those that don't have.

- With This Bridge comenzado a salir de las sombras; hemos comenzado a reventar rutina costumbres opresivas y a aventar los tabues; hemos comenzado a acarrear con orgullo la tarea de deshelar corazones y cambiar conciencias (we have begun to come out of the shadows; we have begun to break with routines and oppressive customs and to discard taboos; we have commenced to carry with pride the task of thawing hearts and changing consciousness). Mujeres, a no dejar que el peligro del viaje y la inmensidad del territorio nos asuste-a mirar hacia adelante y a abrir paso en el monte (Women, let's not let the danger of the journey and the vastness of the territory scare us-let's look forward and open paths in these woods). Caminante, no hay puentes, se hacen puentes al andar (Voyager, there are no bridges, one builds them as one walks).

2001 Forward to 3rd edition

edit- Like a stone thrown into a pool, this book's ripples have touched people on numerous shores, affecting scholars and activists throughout the world.

- Among the ashes traces of our roots glow like live coals illuminating our past, giving us sustenance for the present and guidance for the future.

- The seed for this book came to me in the mid-seventies in a graduate English class taught by a "white" male professor at the University of Texas at Austin. As a Chicana, I felt invisible, alienated from the gringo university and dissatisfied with both el movimiento Chicano and the feminist movement. Like many of the contributors to Bridge I rebelled, using writing to work through my frustrations and make sense of experiences.

- collectively we've gone far, but we've also lost ground-affirmative action has been repealed, the borders have been closed, racism has taken new forms and it's as pervasive as it was twenty-one years ago. Some of the cracks between the worlds have narrowed, but others have widened-the poor have gotten poorer, the corporate rich have become billionaires. New voices have joined the debate, but others are still excluded.

- Later I taught a course in Chicano Studies titled La Mujer Chicana. Having difficulty finding material that reflected my students' experiences I vowed to one day put Chicanas' and other women's voices between the covers of a book.

- Subtle forms of political correctness, self-censorship, and romanticizing home racial/ethnic/class communities imprison us in limiting spaces. These categories do not reflect the realities we live in, and are not true to our multicultural roots. Liminality, the in-between space of nepantla, is the space most of us occupy. We do not inhabit un mundo but and we need to allow these other worlds and peoples to join in the feminist-of-color dialogue. We must be wary of assimilation but not fear cultural mestizaje. Instead we must become nepantleras and build bridges between all these worlds as we traffic back and forth between them, detribalizing and retribalizing in different and various communities.

- daring to make connections with people outside our "race" necessitates breaking down categories. Because our positions are nos/otras, both/and, inside/outside, and inner exiles we see through the illusion of separateness. We crack the shell of our usual assumptions by interrogating our notions and theories of race and other differences. When we replace the old story (of judging others by race, class, gender, and sexual groupings and using these judgments to create barriers), we threaten people who believe in clearly defined mutually exclusive categories. The same hands that split assumptions apart exchange of stories.

- Our images/feelings/thoughts have to be conflicted before we see the need for change.

- For positive social change to happen we need to envision a different reality, dream new blueprints for it, formulate new strategies for coping in it.

- May our voices proclaim the bonds of bridges.

Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality (2015)

edit- Though modern therapies exhort you to act against your passions (compulsions), claiming health and integration lies in that direction, you've learned that delving more fully into your pain, anger, despair, depression will move you through them to the other side, where you can use their energy to heal.

- The solution to your depression lies en esa cueva oscura [in this dark cave] and a deeper integration of your psyche.

- p. 111

Quotes about Gloria Anzaldúa

edit- Her work is an exemplar of how to interpret from experience, and it also directs our attention to a process of connection between ourselves as women, and across the many boundaries of difference.

- Bettina Aptheker Tapestries of Life: Women's Work, Women's Consciousness, and the Meaning of Daily Experience (1989)

- Gloria Anzaldúa declares: "I will not glorify those aspects of my culture which have injured me and which have injured me in the name of protecting me. So don't give me your tenets and your laws. Don't give me your lukewarm gods. What I want is an accounting with all three cultures-white, Mexican, Indian." In her demand for "an accounting" with the many cultures and communities that define her identity, Anzaldúa articulates una cultura mestiza, an agonistic and innovative feminism whose democratic receptivity is characterized by its emphasis on contentious encounters that cut across multiple axes of difference.

- Cristina Beltrán, The trouble with unity : Latino politics and the creation of identity (2010)

- Early on, I was informed by theorists such as Cixous, Said, Spivak, Gates and mostly postcolonial and feminist theorists. I learned a lot from the black arts movement. I loved reading black feminist thinkers on my own (outside of academia)—Audre Lorde, Barbara Smith, Angela Davis, June Jordan, bell hooks, etc. Tough women poets/thinkers like Gloria Anzaldua and Tri Min Ha. And of course, Adrienne Rich.

- Marilyn Chin Interview with Asian Review of Books (2020)

- "This is the oppressor's languages yet I need it to talk to you." Adrienne Rich's words...I know that it is not the English language that hurts me, but what the oppressors do with it, how they shape it to become a territory that limits and defines, how they make it a weapon that can shame, humiliate, colonize. Gloria Anzaldúa reminds us of this pain in Borderlands/La Frontera when she asserts, "So, if you want to really hurt me, talk badly about my language."

- bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom (1994)

- Gloria Anzaldúa has consistently modelled commitment to writing as a life-organizing principle; in addition, Gloria, an old friend, and Chrystos, a new one, gave me courage to write honestly about violence.

- Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, "Acknowledgements" in The Issue Is Power (1992)

- Shame is a knife that carves out a culture's heart. To name, describe and defy shame is thus a profoundly rebellious, strengthening act, and nobody writes about shame like Gloria Anzaldúa-the shame of the other, the minority, the one whose face, hair, eyes, skin, speech, sexuality is different, not right...Those familiar with Anzaldúa's writing from This Bridge Called My Back, the groundbreaking collection she co-edited with Cherrie Moraga, know her as one of the most important and original voices of Third World feminism. In the borderlands new creatures come into being, including the "new mestiza" Anzaldúa celebrates in some of the boldest experimental writing to come out of the women's movement. Monique Wittig comes to mind, experimenting with language as well as form, or June Arnold, or the innovative English/Yiddish poetry of Irena Klepfisz, cited several times by Anzaldúa...the dominant note in the book is neither scolding nor grim. Anzaldúa loves her culture, language, people. Many of the poems are wildly humorous or optimistic simply by dint of their inventiveness ("Interface" or "Holy Relics," for example). She invokes new human possibility in the name of the new mestiza charged with pulling the human race into a future free from destruction, exploitation or oppression.

- Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz "Crossover Dreams" (1988) in The Issue is Power (1992)

- In the '80s, when I -- I've written about this -- I was rooming with Gloria Anzaldúa, who was a Chicana lesbian writer from Texas. And we were teaching in a program in Santa Cruz -- a summer three-week -- I think it was a three-week program. It was called Women's Voices, and it was about -- it was a writing program,...We sort of introduced ourselves to each other, and -- she did ask me how come I never used Yiddish, and I thought that was sort of an interesting question, since it had never even occurred to me. I mean, I think I used two Yiddish words up until then.

- Irena Klepfisz Oral History interview with Yiddish Book Center (2017)

- The most striking change during the past 20 years can be seen in attitudes toward homophobia. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, an almost total silence hung over gay and lesbian advocacy. No openly gay person could be a movement leader. Today homophobia persists; most progressive, straight Chicanos as well as Chicanas still fail to see gay and lesbian rights as another struggle of other oppressed people. Too many still fail to see homophobia as a sometimes murderous force of discrimination. But the situation has improved, especially in some major cities, in academia and among youth...The work of Chicana lesbian artists and intellectuals such as Gloria Anzaldúa and Cherríe Moraga has been crucial to this liberation, with benefits going beyond las lesbianas. Wherever one finds strong voices for women among Chicanas, they often come from Lesbians.

- Elizabeth Martinez, De Colores Means All of Us (1998)

- "To survive the borderlands/you must live sin fronteras/be a crossroads." Those words convey Gloria E. Anzaldúa's essence as she wrote so powerfully about the many kinds of borderlands we confront in life...Her death from diabetes marks the loss of a great feminist philosopher whose ideas live on.

- Elizabeth Martinez, 500 Years of Chicana Women's History/500 Años de la Mujer Chicana (2008)

- I saw Anzaldúa in action at a workshop on the creative process. "How's that for drama?" she asked us, having covered a portable blackboard with drawings. "I lecture with pictures," she explained, going on to trace the significance of these personal hieroglyphics. After she read us one of her poems in Spanish: "I know that was frustrating for many of you, but I wanted you to see what it feels like to be locked out of the language because you don't know it. I was punished for speaking Spanish in school."

- Donna Marie Perry in Backtalk : women writers speak out (1993)

- Gloria Anzaldúa, disentangling the heavy hanging strands fringing the cave of mestiza consciousness, finds speechlessness compounded by femaleness, and both by the fact of being alien, "queer," not a woman in her culture's eyes. Her sense of identity is more complicated than Baca's because she's forced to transform many layers of negativity surrounding femaleness itself-images of Malintzin, the Indian woman as betrayer, of la chingada, the Indian woman as the fucked-one, of la Llorona, eternally mourning, long-suffering mother-and to confront the despot duality of simplistic masculine/feminine: I, like other queer people, am two in one body, both male and female. I am the embodiment of the hieros gamos: the coming together of opposite qualities within."

- Adrienne Rich, “A Poet's Education”

- What W. E. B. Du Bois described as the "veil" that barred African Americans from the White American world can be productively understood in relation to Latinx subjectivities by drawing on Anzaldúa's theorization of exclusion in Borderlands/La Frontera (1987). For Anzaldúa, borders are recursive structures that can be reproduced on a number of scales, such that the "color line" (in Du Bois' terms) is just one of many possible sites for the production of exclusion and double-consciousness. In her formulation of a New Mestiza Consciousness, the racial and economic exclusion caused by colonialism must always be understood in relation to the sexual and gender domination of patriarchy. Anzaldúa's Chicana feminism involves the experience of multiple forms of double-consciousness in response to the multiplicity of power. In some places, Anzaldúa characterizes her lesbian Chicana feminist consciousness as a "Shadow-Beast... that refuses to take orders from outside authorities... that hates constraints of any kind, even those self-imposed" (1987:38)...What Du Bois' navigates as transcendence around and above the exclusionary veil, allowing him to access both the Black and White worlds, Anzaldúa approaches with a hopeful ambivalence: she is without country as a Mestiza, yet possesses all countries through the potential for feminine kinship: she is without race as a lesbian, yet identifies with all races as part of a queer diaspora; and she is without culture as a staunch critic of patriarchal beliefs and practices, yet fully cultural as a creative participant in the production of an emergent reality (1987:102-103).

- Jonathan Rosa, Looking Like a Language, Sounding Like a Race: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and the Learning of Latinidad (2019)

- The works of Chicana lesbian writers Gloria Anzaldúa, Cherrie Moraga, Emma Pérez, Ana Castillo, Alicia Gaspar de Alba, Carla Trujillo, and many others bring out the pain and isolation, but, as important, their joys, self-respect, courage, and dignity.

- Vicki L. Ruiz, From Out of the Shadows: Mexican Women in Twentieth-Century America

- The migrants' plight has transformed border crossings into a key image in contemporary Latin American art and poetry. José Martí, who lived in exile in New York, said that shame of the indigenous mother culture is at the core of Latin America's dependency, fueling the sell-out of natural resources and the cycle of poverty. Gamaliel Churata concurs. It is no coincidence that the main theorization on this issue has come from the work of Gloria Anzaldúa, a mestiza born and raised on the border. She writes: "The U.S. Mexican border is an open wound where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds. . . . We, indias y mestizas, police the Indian in us, brutalize and condemn her." In her work, the negative space that defines women by what they "are not" (nonwhite, non-male), is transformed into creative space, by a will "to fashion my own gods out of my entrails. " Her work indicates the difficult edge all mestizos navigate, the hidden rage and complex paradoxes that women poets often acknowledge.

- Cecilia Vicuña The Oxford Book of Latin American Poetry (2009)