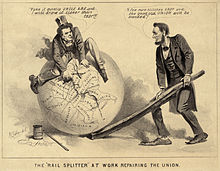

Editorial cartoon

illustration used to comment on current events and personalities

An editorial cartoon better known as a political cartoon, is a drawing containing a commentary expressing the artist's opinion. An artist who writes and draws such images is known as an editorial cartoonist. They typically combine artistic skill, hyperbole and satire in order to question authority and draw attention to corruption, political violence and other social ills.

Quotes

edit- It’s what we do as cartoonists, to cut through the [bull] and expose it.

- Lalo Alcaraz 2022 interview

- I cartoon because I got tired of feeling excluded from the comic stage...We’re not here to fix the world’s problems but to shine a big, fat light on them hopefully.

- Lalo Alcaraz 2021 interview

- my slogan is “The Pen is Funnier than the Sword”—which I really believe. I’m committed to non-violent change.

- I’m an idealist and an optimist: all my political work is aimed at helping usher in a better world. I believe that political cartooning should be almost a form of activism, not just idle commentary for the sake of commentary.

- Khalil Bendib Interview (2015)

- As a political cartoonist, Thomas Nast wielded more influence than any other artist of the 19th century. He not only enthralled a vast audience with boldness and wit, but swayed it time and again to his personal position on the strength of his visual imagination. Both Lincoln and Grant acknowledged his effectiveness in their behalf, and as a crusading civil reformer he helped destroy the corrupt Tweed Ring that swindled New York City of millions of dollars. Indeed, his impact on American public life was formidable enough to profoundly affect the outcome of every presidential election during the period 1864 to 1884.

- Albert Boime, "Thomas Nast and French Art," American Art Journal (1972) 4#1 pp. 43–65

- There are many taboos, intolerance and extremism. And our task is — to destroy them. I believe that clever and artistic, reasoned and convincing humor can push more and more walls in our world. And it can be done without insult or aggression.

- Ángel Boligán Interview (2022)

- Few people have any adequate conception of the cartoon as a factor in political agitation and social progress...A score of pages of the most graphic writing could not be so effective...It is one of the most subtle of educational forces. Its evolution has been slow under capitalism, but is being rapidly accelerated with the growth of Socialism. The true art of the untrammelled cartoonist is now being developed and he will be one of the most inspiring factors in the propaganda of the revolution. No more is the cartoonist compelled to prostitute his genius and traffic in his art. The prizes of capitalism no longer tempt him; its chains of dependence no longer hold him captive...[the social cartoonist] is the social conscience, the social sense of duty, the social love and the social inspiration, and his the thrillingly joyous and self-imposed task to redeem the art of pictorial appeal from gross and sordid commercialism and consecrate it to the cause of freedom and the service of humanity.

- Eugene Debs "The Cartoonist and the Social Revolution" introduction to Red Portfolio (1912)

- Political cartoons and other graphic images had depicted the possible social catastrophes surrounding female advancement since before te creation of the United States (Franzen and Ethiel), Woman Suffrage , for instance, held a multitude of possible horrors: usually, cartoons depicted a woman in a tie, smoking a (Freudian) cigar and dominating a man, often her husband. In this logic, a woman with the masculine prerogative of the vote would naturally become masculinized, wearing pants and sitting in indelicate poses. If women became masculine the equal and opposite reaction was that men would then become feminine, adopting female duties and behaviors like childcare and homemaking. The cartoons depicting and negotiating these fears addressed social apradigms about women's roles, about masculinity and feminimity and they set an historical precedent in graphic are for later representations of women.

- Donna B. Knaff, "A Most Thrilling Struggle Wonder Woman as Wartime and Post-War Feminist" in The Ages of Wonder Woman: Essays on the Amazon Princess in Changing Times, edited by Joeph J Darowski, p.22-23.

- Throughout my my career – which began in 1990 right when the press became unionized – the themes have generally been social-political issues: police brutality, state terrorism, corruption, political maneuvers…And not just in Brazil, the themes I tackle looking abroad include war, armed conflicts, and torture. I’ve also done a lot about the Brazilian military dictatorship.

- Carlos Latuff Interview with Brasilwire (2017)

- What would a respectful political cartoon look like?

- Salman Rushdie, at a Dalkey Book Festival debate; as quoted in "Salman Rushdie: ‘You have to accept a certain level of disrespect’" Sorcha Hamilton, The Irish Times, Jul 21, 2014.

- I, for one, think good political cartoons retain their value for decades. You can learn a lot from those old Doonesbury books. I might add that we cartoonists who lambasted the Bush administration from the beginning have been proven more accurate than most of the highly-paid gasbags you see on television. Historians and television producers, please take note.

- Jen Sorensen Slowpoke: One Nation, Oh My God! (2008)

- Cartoons are a great medium for demonstrating just how absurd something is, without ever having to say it directly.

- Jen Sorensen Interview in Attitude: The New Subversive Cartoonists edited by Ted Rall (2002)

- The thing I like most about political cartooning is the relevance of the work to the real world. And if you do this long enough you get to look back and see yourself in historical context, sometimes on the right side and sometimes on the wrong. But I’m proud of the work I was doing in the runup that bamboozled us into the Iraq War and that horrible chapter where Cheney and Bush drove the country into the ditch, the one we’re still in.

- Matt Wuerker Interview with Washington City Paper] (2010)

- The self-righteously bitter cartoons that appear in sectarian magazines are fine if all you want to do is preach to the choir, but I believe you can reach a lot more people with humor.

- Matt Wuerker interview in Attitude) (2002), edited by Ted Rall

- In my youth I hoped for no higher status in life than to be among those who would follow in the wake of Thomas Nast, Joseph Keppler, and Bernard Gillam, outstanding artists in the field of political caricature. And when in my early twenties I grew familiar with the political and social satires of the graphic artists of England and France across two centuries, these gave even greater stimulus to my ambition. Dreamily I anticipated that my destiny was to succeed as a caricaturist of some influence in public affairs.

- Art Young: His Life and Times (1939)

- I was in deadly earnest about developing my talent, and carousing had no lure for me. I applied myself assiduously to the work in hand, and as I proceeded I became more and more convinced that graphic art was my road to recognition. Painting interested me no less, but I thought of it as having no influence. If one painted a portrait, or a landscape, or whatever, for a rich man to own in his private gallery, what was the use? On the other hand, a cartoon could be reproduced by simple mechanical processes and easily made accessible to hundreds of thousands. I wanted a large audience.

- Art Young: His Life and Times (1939)

External links

edit| This article is a stub. You can help out with Wikiquote by expanding it! |