Culture and Value

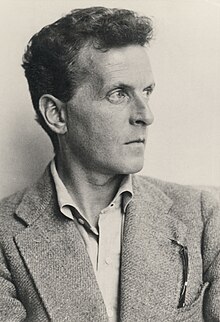

Culture and Value is a selection from the personal notes of Ludwig Wittgenstein made by Georg Henrik von Wright. It was first published in German as Vermischte Bemerkungen in 1977. The text was emended in following editions. An English translation by Peter Winch was printed in 1980, and reprinted in 1984. Ten years later Alois Pichler revised the original edition, and the resulting version was published in 1998 with a new translation by Peter Winch.

Quotes

edit1914 (p.1)

edit1929 (p.1)

edit1930 (p.3)

edit- Niemand kann einen Gedanken für mich denken, wie mir niemand als ich den Hut aufsetzen kann.

- No one can think a thought for me, just as no one can don my hat for me.

- p. 4

- No one can think a thought for me, just as no one can don my hat for me.

- Mein Ideal ist eine gewisse Kühle. Ein Tempel der den Leidenschaften als Umgebung dient ohne in sie hineinzureden.

- My ideal is a certain coolness. A temple providing a setting for the passions without meddling with them.

- p. 4

- My ideal is a certain coolness. A temple providing a setting for the passions without meddling with them.

1930 (p.3)

editZu einem Vorwort: (Sketch for a Foreword) (p.6)

edit1931 (p.8)

edit- Ich denke tatsächlich mit der Feder, denn mein Kopf weiß oft nichts von dem, was meine Hand schreibt.

- I really do think with my pen, because my head often knows nothing about what my hand is writing.

- p. 17

- I really do think with my pen, because my head often knows nothing about what my hand is writing.

(section not confirmed)

edit- Beinahe ähnlich, wie man sagt, daß die alten Physiker plötzlich gefunden haben, daß sie zu wenig Mathematik verstehen. um die Physik bewältigen zu können, kann man sagen, daß die jungen Menschen heutzutage plötzlich in der Lage sind, daß der normale, gute Verstand für die seltsamen Ansprüche des Lebens nicht mehr ausreicht. Es ist alles so verzwickt geworden, daß es zu bewältigen, ein ausnahmsweiser Verstand gehörte. Denn es genügt nicht mehr, das Spiel gut spielen zu können; sondern immer wieder ist die Frage: ist dieses Spiel jetzt überhaupt zu spielen und welches ist das rechte Spiel?

- Earlier physicists are said to have found suddenly that they had too little mathematical understanding to cope with physics; and in almost the same way young people today can be said to be in a situation where ordinary common sense no longer suffices to meet the strange demands life makes. Everything has become so intricate that mastering it would require an exceptional intellect. Because skill at playing the game is no longer enough; the question that keeps coming up is: can this game be played at all now and what would be the right game to play?

- p. 31

- Earlier physicists are said to have found suddenly that they had too little mathematical understanding to cope with physics; and in almost the same way young people today can be said to be in a situation where ordinary common sense no longer suffices to meet the strange demands life makes. Everything has become so intricate that mastering it would require an exceptional intellect. Because skill at playing the game is no longer enough; the question that keeps coming up is: can this game be played at all now and what would be the right game to play?

- Auch Gedanken fallen manchmal unreif von Baum.

- Ideas, too, sometimes fall from the tree before they are ripe.

- p. 32

- Ideas, too, sometimes fall from the tree before they are ripe.

- Wenn man z. B. gewisse bildhafte Sätze als Dogmen des Denkens für die Menschen festlegt, so zwar, dass man damit nicht Meinungen bestimmt, aber den Ausdruck aller Meinungen völlig beherrscht, so wird dies eine sehr eigentümliche Wirkung haben. Die Menschen werden unter einer unbedingten, fühlbaren Tyrannei leben, ohne doch sagen zu können, daß sie nicht frei sind. Ich meine, daß die Katholische Kirche es irgendwie ähnlich macht.

- If certain graphic propositions for instance are laid down for human beings as dogmas governing thinking, namely in such a way that opinions are not thereby determined, but the expression of opinions is completely controlled, this will have a very strange effect. People will live under an absolute, palpable tyranny, yet without being able to say they are not free. I think the Catholic Church does something like this.

- p. 32

- If certain graphic propositions for instance are laid down for human beings as dogmas governing thinking, namely in such a way that opinions are not thereby determined, but the expression of opinions is completely controlled, this will have a very strange effect. People will live under an absolute, palpable tyranny, yet without being able to say they are not free. I think the Catholic Church does something like this.

- Auch im Denken gibt es eine Zeit des Pflügens und eine Zeit der Ernte.

- With thinking too there is a time for ploughing and a time for harvesting.

- p. 33

- With thinking too there is a time for ploughing and a time for harvesting.

- Wenn ich für mich denke ohne ein Buch schreiben zu wollen, so springe ich um das Thema herum; das ist die einzige mir natürliche Denkweise. In einer Reihe gezwungen fortzudenken ist mir eine Qual.

- When I think for myself without wanting to write a book, I jump around the topic; that is the only natural way for me to think. Forcing my thoughts into an ordered sequence is a torment for me.

- p. 33

- When I think for myself without wanting to write a book, I jump around the topic; that is the only natural way for me to think. Forcing my thoughts into an ordered sequence is a torment for me.

- Ich verschwende unsägliche Mühe auf ein Anordnen der Gedanken, das vielleicht gar keinen Wert hat.

- I squander untold effort putting my thoughts into an order that may have no value at all.

- p. 33

- I squander untold effort putting my thoughts into an order that may have no value at all.

- Nichts ist so schwer, als sich nicht betrügen.

- Nothing is so difficult as not deceiving oneself.

- p. 39

- Nothing is so difficult as not deceiving oneself.

- Im Rennen der Philosophie gewinnt, wer am langsamsten laufen kann. Oder: der, der das Ziel zuletzt erreicht.

- In philosophy the race goes to the one who can run slowest—the one who crosses the finish line last.

- p. 40

- In philosophy the race goes to the one who can run slowest—the one who crosses the finish line last.

- Das Genie hat nicht mehr Licht als ein andrer, rechtschaffener Mensch—aber es sammelt dies Licht durch eine bestimmte Art von Linse in einen Brennpunkt.

- There is no more light in a genius than in any other honest man—but he concentrates this light with a special kind of lens into a focus.

- p. 41

- There is no more light in a genius than in any other honest man—but he concentrates this light with a special kind of lens into a focus.

- Man kann nicht die Wahrheit sagen, wenn man sich noch nicht selbst bezwungen hat. … Nur der kann sie sagen der schon in ihr ruht; nicht der, der noch in der Unwahrheit ruht, und nur einmal aus der Unwahrheit heraus nach ihr langt.

- One cannot say the truth until one has overcome oneself. The truth can be spoken only by someone who is already at home in it; not by someone who still lives in untruthfulness, and who attains it only once from within untruthfulness.

- p. 41

- One cannot say the truth until one has overcome oneself. The truth can be spoken only by someone who is already at home in it; not by someone who still lives in untruthfulness, and who attains it only once from within untruthfulness.

- Meine Originalität, (wenn das das richtige Wort ist), ist, glaube ich, eine Originalität des Bodens, nicht des Samens. … Wirf einen Samen in meinen Boden, und er wird anders wachsen, als in irgend einem andern Boden.

- My originality (if that is the right word) is, I believe, an originality that belongs to the soil, not the seed. ... Sow a seed in my soil, and it will grow differently than it would in any other soil.

- p.42

- My originality (if that is the right word) is, I believe, an originality that belongs to the soil, not the seed. ... Sow a seed in my soil, and it will grow differently than it would in any other soil.

- Die Menschen heute glauben, die Wissenschaftler seien da, sie zu belehren, die Dichter und Musiker, etc., sie zu erfreuen. Daß diese sie etwas zu lehren haben; kommt ihnen nicht in den Sinn.

- People nowadays think that scientists exist to instruct them, poets, musicians, etc. to give them pleasure. It does not occur to them that the latter have something to teach them.

- p. 36

- People nowadays think that scientists exist to instruct them, poets, musicians, etc. to give them pleasure. It does not occur to them that the latter have something to teach them.

- Ein Lehrer, der während des Unterrichts gute, oder sogar erstaunliche Resultate aufweisen kann, ist darum noch kein guter Lehrer, denn es ist möglich, daß er seine Schüler, während sie unter seinem unmittelbaren Einfluß stehen, zu einer ihnen unnatürlichen Höhe emporzieht, ohne sie doch zu dieser Höhe zu entwickeln, so daß sie sofort zusammensinken, wenn der Lehrer die Schulstube verläßt.

- A teacher who can show good, or even amazing results when he teaches, is still not necessarily a good teacher, for it could be that, while his pupils are under his immediate influence, he elevates them to a level that is not natural to them, but without letting them develop to that level, such that they promptly drop when the teacher leaves the classroom.

- p. 43

- A teacher who can show good, or even amazing results when he teaches, is still not necessarily a good teacher, for it could be that, while his pupils are under his immediate influence, he elevates them to a level that is not natural to them, but without letting them develop to that level, such that they promptly drop when the teacher leaves the classroom.

- Der Mut, nicht die Geschicklichkeit; nicht einmal die Inspiration, ist das Senfkorn, was zum großen Baum empor wächst.

- Courage, not ability, nor even inspiration, is the mustard seed that grows up to be a great tree.

- p. 44

- Courage, not ability, nor even inspiration, is the mustard seed that grows up to be a great tree.

- Dadurch, daß man den Mangel an Mut in einem Andern einsieht, erhält man selbst nicht Mut.

- It is not by recognizing the want of courage in someone else that you acquire courage yourself.

- p. 44

- It is not by recognizing the want of courage in someone else that you acquire courage yourself.

- Du kannst nicht die Lüge nicht aufgeben wollen und die Wahrheit sagen.

- You can’t be reluctant to give up lying and still tell the truth.

- p. 44

- You can’t be reluctant to give up lying and still tell the truth.

- Der Philosoph ist der, der in sich viele Krankheiten des Verstandes heilen muß, ehe er zu den Notionen des gesunden Menschenverstandes kommen kann.

- The philosopher is someone who has to heal many diseases of the understanding in himself, before he can reach the notions of sound common sense.

- p. 50

- The philosopher is someone who has to heal many diseases of the understanding in himself, before he can reach the notions of sound common sense.

- Wenn wir im Leben vom Tod umgeben sind, so auch in der Gesundheit des Verstands von Wahnsinn.

- We are surrounded by death in life, as healthy understanding is surrounded by madness.

- p. 50, modified translation

- We are surrounded by death in life, as healthy understanding is surrounded by madness.

- Worte sind Taten.

- Words are deeds.

- p. 50

- Words are deeds.

- The way you use the word “God” does not show whom you mean—but, rather, what you mean.

- p. 50

- Je weniger sich Einer selbst kennt und versteht um so weniger groß ist er, wie groß auch sein Talent sein mag. Darum sind unsre Wissenschaftler nicht groß. Darum sind Freud, Spengler, Kraus, Einstein nicht groß.

- The less one knows and understands oneself, the less one's stature is, however great one's talent might be. That's why our scientists are not great. That's why Freud, Spengler, Kraus, Einstein are not great.

- p. 51

- The less one knows and understands oneself, the less one's stature is, however great one's talent might be. That's why our scientists are not great. That's why Freud, Spengler, Kraus, Einstein are not great.

- Es ist schwer sich recht zu verstehen, denn dasselbe, was man aus Größe und Güte tun könnte, kann man aus Feigheit oder Gleichgültigkeit tun.

- It is hard to understand oneself properly, for what one might be able to do out of greatness or goodness, one can also do out of cowardice and indifference.

- p. 54

- It is hard to understand oneself properly, for what one might be able to do out of greatness or goodness, one can also do out of cowardice and indifference.

- Es ist merkwürdig, wie schwer es fällt, zu glauben, was wir nicht selbst einsehen. Wenn ich z. B. bewundernde Äußerungen der bedeutenden Männer mehrerer jahrhunderte über Shakespeare höre. so kann ich mich eines Mißtrauens nie erwehren, es sei eine Konvention gewesen, ihn zu preisen; obwohl ich mir doch sagen muß daß es so nicht ist. Ich brauche die Autorität einer Milton um wirklich überzeugt zu sein. Bei diesem nehme ich an daß er unbestechlich war. Damit meine ich aber natürlich nicht daß nicht eine ungeheure Menge Lobes ohne Verständnis und aus falschen Gründen Shakespeare gespendet worden ist und wird, von tausend Professoren der Literatur.

- It is remarkable how hard it is to believe something that we do not see for ourselves. If, for example, I hear admiration for Shakespeare expressed by great men over centuries, I can't rid myself of the suspicion that praising him has been a matter of convention, even though I have to tell myself that this is not the case. I need the authority of a Milton to be really convinced. In his case, I assume that he was incorruptible.—But of course I don’t mean to deny by this that an enormous amount of praise has been and will be lavished on Shakespeare for the wrong reasons and without understanding by a thousand professors of literature.

- p. 55

- It is remarkable how hard it is to believe something that we do not see for ourselves. If, for example, I hear admiration for Shakespeare expressed by great men over centuries, I can't rid myself of the suspicion that praising him has been a matter of convention, even though I have to tell myself that this is not the case. I need the authority of a Milton to be really convinced. In his case, I assume that he was incorruptible.—But of course I don’t mean to deny by this that an enormous amount of praise has been and will be lavished on Shakespeare for the wrong reasons and without understanding by a thousand professors of literature.

- Man könnte Gedanken Preise anheften. Manche kosten viel manche wenig. … Und womit zahlt man für Gedanken? Ich glaube: mit Mut.

- You could attach prices to ideas. Some cost a lot some little. ... And how do you pay for ideas? I believe: with courage.

- p. 60

- You could attach prices to ideas. Some cost a lot some little. ... And how do you pay for ideas? I believe: with courage.

- Wenn das Leben schwer erträglich wird, denkt man an Verbesserungen. Aber die wichtigste und wirksamste Verbesserung, die des eigenen Verhaltens, kommt uns kaum in Sinn, und zu ihr können wir uns am allerschwersten entschließen.

- If life becomes hard to bear we think of improvements. But the most important and effective improvement, in our own behavior, hardly occurs to us, and we can resolve ourselves to it only with the utmost difficulty.

- p. 60

- If life becomes hard to bear we think of improvements. But the most important and effective improvement, in our own behavior, hardly occurs to us, and we can resolve ourselves to it only with the utmost difficulty.

- Wenn das Leben schwer erträglich wird, denkt man an eine Veränderung der Lage. Aber die wichtigste und wirksamste Veränderung, die des eignen Verhaltens, kommt uns kaum in den Sinn, und zu ihr können wir uns schwer entschließen.

- If life becomes hard to bear we think of a change in our circumstances. But the most important and effective change, a change in our own attitude, hardly even occurs to us, and the resolution to take such a step is very difficult for us.

- p. 53

- If life becomes hard to bear we think of a change in our circumstances. But the most important and effective change, a change in our own attitude, hardly even occurs to us, and the resolution to take such a step is very difficult for us.

- Eine Pointe im Gedicht ist überspitzt, wenn die Verstandesspitzen nackt zu Tage treten, nicht überkleidet vom Herzen.

- The lesson in a poem has too sharp a point to it if the tips of the intellect stick out too obviously, without being sheathed by the heart.

- p. 62

- The lesson in a poem has too sharp a point to it if the tips of the intellect stick out too obviously, without being sheathed by the heart.

- Kann ich nur keine Schule gründen, oder kann es ein Philosoph nie?

- Is it just I who cannot found a school, or can a philosopher never do so?

- p. 69

- Is it just I who cannot found a school, or can a philosopher never do so?

- Ich kann keine Schule gründen, weil ich eigentlich nicht nachgeahmt werden will. Jedenfalls nicht von denen, die Artikel in philosophischen Zeitschriften veröffentlichen.

- I cannot found a school, because I actually do not want to be imitated. In any case not by those who publish articles in philosophical journals.

- p. 69

- I cannot found a school, because I actually do not want to be imitated. In any case not by those who publish articles in philosophical journals.

- Man vergißt immer wieder, auf den Grund zu gehen. Man setzt die Fragezeichen nicht tief genug.

- One keeps forgetting to go down to the bottom of things. One doesn’t set the question marks deep down enough.

- p. 71

- One keeps forgetting to go down to the bottom of things. One doesn’t set the question marks deep down enough.

- Wer zu viel weiß, für den ist es schwer nicht zu lügen.

- He who knows too much finds it hard not to lie.

- p. 73 [my translation]

- He who knows too much finds it hard not to lie.

- Es kommt mir vor als könne ein religiöser Glaube nur (etwas wie) das leidenschaftliche sich entscheiden zu einem Koordinatesystem sein.

- It seems to me that a religious belief is only (something like) passionately deciding upon a coordinate system.

- p. 73 [my translation]

- It seems to me that a religious belief is only (something like) passionately deciding upon a coordinate system.

- Es liegen in diesen schwächlichen Bemerkungen große Ausblicke verborgen.

- There are great prospects hidden in these feeble remarks.

- p. 75

- There are great prospects hidden in these feeble remarks.

- Schiller schreibt in einem Brief [an Goethe, 17 Dezember 1795] von einer „poetischen Stimmung”. Ich glaube, ich weiß was er meint, ich glaube sie selbst zu kennen. Es ist die Stimmung, in welcher man für die Natur empfänglich ist und in welcher die Gedanken so lebhaft erscheinen, wie Natur.

- Rosinen mögen das Beste an einem Kuchen sein; aber ein Sack Rosinen ist nicht besser als ein Kuchen, und wer im Stande ist uns einen Sack voll Rosinen zu geben kann damit noch keinen Kuchen backen, geschweige daß er etwas besseres kann.

- Ich denke an Kraus und seine Aphorismen, aber auch an mich selbst und meine philosophischen Bemerkungen.

- Ein Kuchen das ist nicht gleichsam: verdünnte Rosinen.

- Raisins may be the best part of a cake; but a bag of raisins is not better than a cake, and someone who is in a position to give us a bag full of raisins still cannot bake a cake with them, let alone do something better.

- I am thinking of Karl Kraus and his aphorisms, but of myself too and my philosophical remarks.

- A cake is not, as it were: thinned out raisins.

- p. 76

- Die Farben scheinen uns ein Rätsel aufzugeben, ein Rätsel das uns anregt,—nicht aufregt.

- Colours seem to present us with a riddle, a riddle that stimulates us,—not one that exasperates us.

- p. 76

- Colours seem to present us with a riddle, a riddle that stimulates us,—not one that exasperates us.

- Ich möchte eigentlich durch fortwährende Interpunktionszeichen das Tempo des Lesens verzögern. Denn ich möchte langsam gelesen werden. (Wie ich selbst lese.)

- I would really like to slow down the speed of reading with continual punctuation marks. For I would like to be read slowly. (As I myself read.)

- p. 77 [my modified translation]

- I would really like to slow down the speed of reading with continual punctuation marks. For I would like to be read slowly. (As I myself read.)

- Ich möchte mir immer sagen: „Mal wirklich nur, was Du siehst.”

- I would like to keep telling myself: paint only what you see.

- p. 78 [my translation]

- I would like to keep telling myself: paint only what you see.

- Die Probleme des Lebens sind an der Oberfläche unlösbar, und nur in der Tiefe zu lösen. In den Dimensionen der Oberfläche sind sie unlösbar.

- The problems of life are insoluble on the surface, and can only be solved in depth. In surface dimensions they are insoluble.

- p. 84

- The problems of life are insoluble on the surface, and can only be solved in depth. In surface dimensions they are insoluble.

- Nichts ist doch wichtiger, als die Bildung von fiktiven Begriffen, die uns die unseren erst verstehen lernen.

- Nothing is more important than the formation of fictional concepts, which teach us at last to understand our own.

- p. 85 (modified translation)

- Nothing is more important than the formation of fictional concepts, which teach us at last to understand our own.

- Ist ein falscher Gedanke nur einmal kühn und klar ausgedrückt, so ist damit schon viel gewonnen.

- If a false thought is finally expressed boldly and clearly, a great deal has already been achieved.

- p. 86

- If a false thought is finally expressed boldly and clearly, a great deal has already been achieved.

- Nur wenn man noch viel verrückter denkt, als die Philosophen, kann man ihre Probleme lösen.

- Only by thinking even more crazily than the philosophers can one solve their problems.

- p. 86 (modified translation)

- Only by thinking even more crazily than the philosophers can one solve their problems.

- Es ist ein körperliches Bedürfnis des Menschen, sich bei der Arbeit zu sagen „Jetzt lassen wir’s schon einmal”, und daß man immer wieder gegen dieses Bedürfnis beim Philosophieren denken muß, macht diese Arbeit so anstrengend.

- Human beings have a physical need to tell themselves when at work: “Let’s have done with it now,” and it’s having constantly to go on thinking in the face of this need when philosophizing that makes this work so strenuous.

- p. 86

- Human beings have a physical need to tell themselves when at work: “Let’s have done with it now,” and it’s having constantly to go on thinking in the face of this need when philosophizing that makes this work so strenuous.

- Steige immer von den kahlen Höhen der Gescheitheit in die grünenden Täler der Dummheit.

- Always descend from the barren heights of cleverness into the green valleys of stupidity.

- p. 86

- Always descend from the barren heights of cleverness into the green valleys of stupidity.

- Ehrgeiz ist der Tod des Denkens.

- Ambition is the death of thought.

- p. 88

- Ambition is the death of thought.

- Der Sabbath ist nicht einfach die Zeit der Ruhe, der Erholung. Wir sollten unsre Arbeit von außen betrachten, nicht nur von innen.

- The Sabbath is not simply a time to rest, to recuperate. We should look at our work from the outside, not just from within.

- p. 91 [modified translation]

- The Sabbath is not simply a time to rest, to recuperate. We should look at our work from the outside, not just from within.

- Der Gruß der Philosophen unter einander sollte sein: „Laß Dir Zeit!”

- This is how philosophers should greet each other: “Take your time.”

- p. 91

- This is how philosophers should greet each other: “Take your time.”

- Eine Zeit mißversteht die andere; und eine kleine Zeit mißversteht alle andern in ihrer eigenen häßlichen Weise.

- One age misunderstands another; and a petty age misunderstands all the others in its own ugly way.

- p. 98

- One age misunderstands another; and a petty age misunderstands all the others in its own ugly way.

- Die Philosophie hat keinen Fortschritt gemacht?—Wenn einer kratzt wo es ihn juckt, muß ein Fortschritt sehen zu sein? ist es sonst kein echtes Kratzen, order kein echtes Jucken?

- Philosophy hasn’t made any progress?—If someone scratches where it itches, do we have to see progress? Is it not genuine scratching otherwise, or genuine itching?

- p. 98

- Philosophy hasn’t made any progress?—If someone scratches where it itches, do we have to see progress? Is it not genuine scratching otherwise, or genuine itching?

- Man könnte sagen: „Genie ist Mut im Talent.”

- One could say: genius is having the courage of one's talent.

- p. 38

- One could say: genius is having the courage of one's talent.