Christian atheism

atheism while following the other teachings of Jesus

Christian atheism is a philosophical stance in which beliefs in conventional Christian notions of God are absent, strongly doubted or rejected, but the moral teachings of Jesus are followed.

Quotes

edit- If Protestant theology has reached the point where it is closed to the challenge of atheism, then it has ceased to be the intellectual vanguard of Christianity.

- Thomas J. J. Altizer, Toward a New Christianity (1967), p. 7

- No suffering can be foreign to a Christian, not even the anguish that comes with the loss of God.

- Thomas J. J. Altizer, The Gospel of Christian Atheism (1966), p. 23

- God is the most noble of beings. Now it is impossible for a body to be the most noble of beings; for a body must be either animate or inanimate; and an animate body is manifestly nobler than any inanimate body. But an animate body is not animate precisely as body; otherwise all bodies would be animate. Therefore its animation depends upon some other thing, as our body depends for its animation on the soul. Hence that by which a body becomes animated must be nobler than the body. Therefore it is impossible that God should be a body.

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Part 1, Question 3

- Given that only the religion of pervasive kenosis can be truly universal, no single historical individual can exhaust its fullness by virtue of his redemptive acts, and no religious institution can grasp and articulate its meaning by means of dogmatic or doctrinal teachings. In the last resort, it is in the name of religious universalism that Simone Weil calls for a reversion of historical Christianity to its origins as a religion of kenosis.

- J. Edgar Bauer, in "Simone Weil: Kenotic Thought and "Sainteté Nouvelle" in The 2002 CESNUR International Conference : Minority Religions, Social Change, and Freedom of Conscience (June 2002)

- Honesty compels serious men, on examination of their consciences, to admit that the old faith is no longer compelling. It is the very peak of Christian virtue that demands the sacrifice of Christianity.

- Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind (New York: 1988), pp. 195-196

- In point of fact there are two kinds sorts of mysticism, differing from one another as the ranting of drunkards from the language of illumined spirits. There is the muddled, stammering mysticism, and there is the mysticism luminous with truly ultimate ideas. On the one hand there are the empty dimness and darkness, the barren, chilling sentimentalism and mental debauchery, the foolishly grimacing but rigid phantasms of the Cabbala, of occultism, mysteriosophy and theosophy. We cannot draw too sharp a dividing line between these and the brightness, the simple sincerity, and healthy, rejuvenating strength of genuine mysticism, which takes the most precious gems from philosophy's treasure chest and displays them in the beauty of its own setting. Mysticism is in complete accord with the result, with the sum of philosophy. In fact, mysticism is precisely the sum and the soul of philosophy, in the form of that rapturous, passionate outpouring of love.... We are concerned with an understanding of this serious mysticism, and its meaning could be stated in three words... godlessness... freedom from the world... blessedness of soul.

- Constantin Brunner, Our Christ : The Revolt of the Mystical Genius (1921), as translated by Graham Harrison and Michael Wex, edited by A. M. Rappaport

- Christ, with whom the multitude could not deal other than by making him into God Himself, thus enabling itself to venerate as God him whom they had loathed as man.

- Constantin Brunner, Our Christ : The Revolt of the Mystical Genius (1921), as translated by Graham Harrison and Michael Wex, edited by A. M. Rappaport, p. 113

- Contemporary Christian proclamation is faced with the question whether, when it demands faith from men and women, it expects them to acknowledge this mythical world picture from the past. If this is impossible, it has to face the question whether the New Testament proclamation has a truth that is independent of the mythical world picture, in which case it would be the task of theology to demythologize the Christian proclamation.

- Rudolf Bultmann, New Testament and Mythology and Other Basic Writings (1984), p. 3

- Can the Christian proclamation today expect men and women to acknowledge the mythical world picture as true? To do so would be both pointless and impossible. It would be pointless because there is nothing specifically Christian about the mythical world picture, which is simply the world picture of a time now past which was not yet formed by scientific thinking. It would be impossible because no one can appropriate a world picture by sheer resolve, since it is already given with one’s historical situation.

- Rudolf Bultmann, New Testament and Mythology and Other Basic Writings (1984), p. 3

- It is impossible to repristinate a past world picture by sheer resolve, especially a mythical world picture, now that all of our thinking is irrevocably formed by science. A blind acceptance of New Testament mythology would be simply arbitrariness; to make such acceptance a demand of faith would be to reduce faith to a work. … We cannot use electric lights and radios and, in the event of illness, avail ourselves of modern medical and clinical means and at the same time believe in the spirit and wonder world of the New Testament.

- Rudolf Bultmann,New Testament and Mythology and Other Basic Writings (1984), pp. 3-4

- Thomas is not a Wordsworthian poet, and his “nature” is not Wordsworth’s; it is history, rather than divinity, which he responds to most, in the bleak beauty of Wales. In Christian terms, Thomas is not a poet of the transfiguration, of the resurrection, of human holiness … He is a poet of the cross, the unanswered prayer, the bleak trek through darkness.

- A.E. Dyson, in Yeats, Eliot, and R.S. Thomas : Riding the Echo (1981), p. 296

- "Will to truth" does not mean "I do not want to let myself be deceived" but—there is no alternative—"I will not deceive, not even myself"; and with that we stand on moral ground. . . . You will have gathered what I am getting at, namely, that it is still a metaphysical faith upon which our faith in science rests—that even we knowers of today, we godless anti-metaphysicians, still take our fire, too, from the flame lit by the thousand-year-old faith, the Christian faith which was also Plato's faith, that God is truth; that truth is divine.

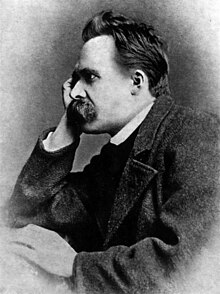

- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science (1882), B. Williams, ed. (2001), § 344

- You see what it was that really triumphed over the Christian God: Christian morality itself, the concept of truthfulness that was understood more rigorously, the father confessor’s refinement of the Christian conscience, translated and sublimated into a scientific conscience, into intellectual cleanliness at any price.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science (1882), as translated by Walter Kaufmann, § 357

- Jesus has a very special love for you. As for me, the silence and emptiness is so great that I look and do not see, listen and do not hear. The tongue moves but does not speak.

- Mother Teresa, in a letter to Michael van der Peet (September 1979), quoted in "Mother Teresa Did Not Feel Christ's Presence for Last Half of Her Life, Letters Reveal", Fox News (24 August 2007)

- I call, I cling, I want … and there is no One to answer … no One on Whom I can cling … no, No One. Alone … Where is my Faith … even deep down right in there is nothing, but emptiness & darkness … My God … how painful is this unknown pain … I have no Faith … I dare not utter the words & thoughts that crowd in my heart … & make me suffer untold agony. So many unanswered questions live within me afraid to uncover them … because of the blasphemy … If there be God … please forgive me … When I try to raise my thoughts to Heaven there is such convicting emptiness that those very thoughts return like sharp knives & hurt my very soul. I am told God loves me … and yet the reality of darkness & coldness & emptiness is so great that nothing touches my soul.

- Mother Teresa, in a letter indicating that, at least at times, Mother Teresa's theological doubts were strong enough to be regarded as Christian atheism, reported by Time (9 March 2007), and quoted in "Was Mother Teresa an atheist?", in The Guardian (24 August 2007)

- Any form of orthodoxy is just not part of a poet's province … A poet must be able to claim … freedom to follow the vision of poetry, the imaginative vision of poetry … And in any case, poetry is religion, religion is poetry. The message of the New Testament is poetry. Christ was a poet, the New Testament is metaphor, the Resurrection is a metaphor; and I feel perfectly within my rights in approaching my whole vocation as priest and preacher as one who is to present poetry; and when I preach poetry I am preaching Christianity, and when one discusses Christianity one is discussing poetry in its imaginative aspects. … My work as a poet has to deal with the presentation of imaginative truth.

- R. S. Thomas, in "R. S. Thomas : Priest and Poet" (BBC TV, 2 April 1972)

- I am a humanist, which mean, in part, that I have tried to behave decently without any expectation of rewards or punishments after I'm dead. My German-American ancestors, the earliest of whom settled in our Middle West about the time of our Civil War, called themselves "Freethinkers," which is the same sort of thing. My great grandfather Clemens Vonnegut wrote, for example, "If what Jesus said was good, what can it matter whether he was God or not?"

I myself have written, "If it weren't for the message of mercy and pity in Jesus' Sermon on the Mount, I wouldn't want to be a human being. I would just as soon be a rattlesnake."- Kurt Vonnegut, in God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian (1999)

- Wrongly or rightly you think that I have a right to the name of Christian. I assure you that when in speaking of my childhood and youth I use the words vocation, obedience, spirit of poverty, purity, acceptance, love of one's neighbor, and other expressions of the same kind, I am giving them the exact signification they have for me now. Yet I was brought up by my parents and my brother in a complete agnosticism, and I never made the slightest effort to depart from it; I never had the slightest desire to do so, quite rightly, I think. In spite of that, ever since my birth, so to speak, not one of my faults, not one of my imperfections really had the excuse of ignorance. I shall have to answer for everything on that day when the Lamb shall come in anger.

You can take my word for it too that Greece, Egypt, ancient India, and ancient China, the beauty of the world, the pure and authentic reflections of this beauty in art and science, what I have seen of the inner recesses of human hearts where religious belief is unknown, all these things have done as much as the visibly Christian ones to deliver me into Christ's hands as his captive. I think I might even say more. The love of these things that are outside visible Christianity keeps me outside the Church... But it also seems to me that when one speaks to you of unbelievers who are in affliction and accept their affliction as a part of the order of the world, it does not impress you in the same way as if it were a question of Christians and of submission to the will of God. Yet it is the same thing.- Simone Weil, in last letter to Father Joseph-Marie Perrin, from a refugee camp in Casablanca (26 May 1942), as translated in The Simone Weil Reader (1957) edited by George A. Panichas, p. 111

- In order to obey God, one must receive his commands. How did it happen that I received them in adolescence, while I was professing atheism? To believe that the desire for good is always fulfilled — that is faith, and whoever has it is not an atheist.

- Simone Weil, in Last Notebook (1942), in First and Last Notebooks (1970), p. 137

- No human being escapes the necessity of conceiving some good outside himself towards which his thought turns in a movement of desire, supplication, and hope. consequently, the only choice is between worshipping the true God or an idol. Every atheist is an idolater — unless he is worshipping the true God in his impersonal aspect. The majority of the pious are idolaters.

- Simone Weil, in Last Notebook (1942), in First and Last Notebooks (1970), p. 308

- Maurras, with perfect logic, is an atheist. The Cardinal [Richelieu], in postulating something whose whole reality is confined to this world as an absolute value, committed the sin of idolatry. … The real sin of idolatry is always committed on behalf of something similar to the State.

- Simone Weil, in Prelude to Politics (1943), as translated in The Simone Weil Reader (1957) edited by George A. Panichas, p. 199

- Religion in so far as it is a source of consolation is a hindrance to true faith; and in this sense atheism is a purification. I have to be an atheist with that part of myself which is not made for God. Among those in whom the supernatural part of themselves has not been awakened, the atheists are right and the believers wrong.

- Simone Weil, in "Faiths of Meditation; Contemplation of the divine" as translated in The Simone Weil Reader (1957) edited by George A. Panichas, p. 417

- That is why St. John of the Cross calls faith a night. With those who have received a Christian education, the lower parts of the soul become attached to these mysteries when they have no right at all to do so. That is why such people need a purification of which St. John of the Cross describes the stages. Atheism and incredulity constitute an equivalent of such a purification.

- Simone Weil, in "Faiths of Meditation; Contemplation of the divine" as translated in The Simone Weil Reader (1957) edited by George A. Panichas, p. 418

- There are two atheisms of which one is a purification of the notion of God.

- Simone Weil, as quoted in The New Christianity (1967) edited by William Robert Miller