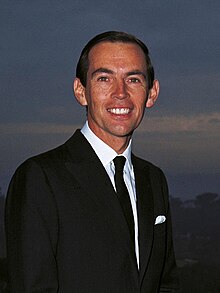

Christiaan Barnard

South African cardiac surgeon

Christiaan Neethling Barnard (8 November 1922 – 2 September 2001) was a South African cardiac surgeon who performed the world's first human-to-human heart transplant on 3 December 1967.

| This physician article is a stub. You can help out with Wikiquote by expanding it! |

Quotes

edit- This mountain, I thought, was like education: The higher you climbed, the farther you could see.

- One Life (New York: Macmillan Company, 1970), p. 49.

- Last year a Dutch animal breeding centre sent me two chimpanzees as a gift. I killed one and cut its heart out. The other wept bitterly and was inconsolable. The sad chimp has long since happily mated again and lives with lots of other animals on a pleasant game farm near Villiersdorp. I vowed never again to experiment with such sensitive creatures, but the memory of that weeping chimp has remained with me. It was taken for granted, of course, that he was weeping for his mate but I've since had some thoughts on the subject which made me wonder whether perhaps he was weeping for the human race. The idea is not as silly as it sounds. In our doings there is much to weep over and even a chimpanzee would never behave in some of the contradictory ways we think of as normal.

- The Best Medicine (Cape Town: Tafelberg Publishers, 1979), p. 38.

- Suffering isn't ennobling, recovery is.

- New York Times, April 28, 1985; as quoted in A Speaker's Treasury of Quotations by Michael C. Thomsett and Linda Rose Thomsett (McFarland, 2009), p. 111.

Attributed

editQuotes about

edit- It seemed little would be without controversy this year. The good news might have been that Christiaan Barnard of the Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa, had successfully transplanted the heart of a twenty-four-year-old into Philip Blaiberg, a fifty-eight-year-old dentist. This was the third heart transplant, the second by Barnard but the first that medical science regarded as successful. Barnard started 1968 and spent much of the year as an international celebrity, signing autographs, giving interviews with his easy smile and quotable statements, which from the outset in January was frowned upon by his profession. Barnard pointed out that despite his sudden fame he still earned only his $8,500 yearly salary. But there were also doubts about his feat. A German doctor called it a crime. A New York biologist, apparently confusing doctors with lawyers, said that he should be “disbarred for life.” Three distinguished American cardiologists called for a moratorium on heart transplants, which Barnard immediately said he would ignore.

- Mark Kurlansky, 1968: The Year that Rocked the World (2004)

- In theory, the operation involves two doomed patients. One gives up his heart and dies but would have died in any event; the other is saved. But some doctors and laymen wondered if doctors should be deciding who is doomed. Shouldn’t everyone hope for a miracle? And how is it decided who receives a new heart? Were doctors now making godlike decisions? The controversy was not helped by Barnard, who said in an interview in Paris Match, “Obviously, if I had to choose between two patients in the same need and one was a congenital idiot and one a mathematics genius, I would pick the latter.” Controversy was also fueled by the fact that Barnard came from South Africa, the increasingly stigmatized land of apartheid, and that he had saved a white man by removing a black man’s heart and implanting it in him. Such an irony was not likely to be overlooked in a year like this.

- Mark Kurlansky, 1968: The Year that Rocked the World (2004)