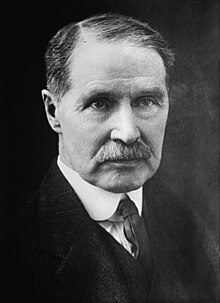

Bonar Law

former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1858-1923)

Andrew Bonar Law (16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a Conservative British statesman and Prime Minister from 1922 to 1923.

Quotes

edit- We who represent the Unionist Party in England and Scotland have supported, and we mean to support to the end, the loyal minority [in Ireland]. We support them not because we are intolerant, but because their claims are just.

- Speech in the Albert Hall (26 January 1912)

- As I crossed a few hours ago from Scotland I said to myself,—"The majority there are Radicals. They are going to vote next week for the Home Rule Bill. What would they say to a proposal which was to subject them to the same kind of Government or the same kind of men to which, for the sake of party interests, they are willing to sacrifice you?" They would never accept it. I know Scotland well, and I believe that, rather than submit to such a fate, the Scottish people would face a second Bannockburn or a second Flodden.

- Speech in Belfast (8 April 1912), quoted in The Times (9 April 1912), p. 7

- These people in the North-east of Ireland, from old prejudices perhaps more from anything else, from the whole of their past history, would prefer, I believe, to accept the government of a foreign country rather than submit to be governed by honourable gentlemen below the gangway [i.e. the Irish Nationalist Party].

- Speech in the House of Commons (1 January 1913) rejecting the Home Rule Bill

- Whatever steps you may feel compelled to take, whether they are constitutional, or whether in the long run they are unconstitutional, you have the whole Unionist Party, under my leadership, behind you.

- Message sent to Belfast (12 July 1913)

- I remember this, that King James had behind him the letter of the law just as completely as Mr. Asquith has now. He made sure of it. He got the judges on his side by methods not dissimilar from those by which Mr. Asquith has a majority in the House of Commons on his side. There is another point to which I would specially refer. In order to carry out his despotic intention the King had the largest army which had ever been seen in England. What happened? There was no civil war. Why? Because his own army refused to fight for him.

- Speech in Dublin (28 November 1913), quoted in The Times (29 November 1913), p. 10

- We cannot alone act as the policeman of the world. The financial and social condition of this country makes that impossible.

- Letter to The Times during the Chanak Crisis, printed in The Times (7 October 1922), p. 11

- I think everyone who has been in business knows that instability or restlessness of any kind has one of the worst effects upon industry of all kinds. It is for that reason that I expressed the view that what is most needed now, and what it will be our business to try to produce, is a feeling of tranquillity and stability. (Cheers.) In other words, I think we must have as little legislation as possible (cheers)—that we must leave things alone more or less where we can.

- Speech in St. Andrew's Hall, Glasgow, opening the Conservative Party's election campaign (26 October 1922), quoted in The Times (27 October 1922), p. 7

- The crying need of the nation at this moment—a need which in my judgment far exceeds any other—is that we should have tranquillity and stability both at home and abroad so that free scope should be given to the initiative and enterprise of our citizens, for it is in that way far more than by any action of the Government that we can hope to recover from the economic and social results of the war.

- Election manifesto (4 November 1922), quoted in Robert Blake, The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858–1923 (1955), p. 466

- There are many measures of legislative and administrative importance which in themselves would be desirable and which in other circumstances I should have recommended to the immediate attention of the electorate. But I do not feel that they can, at this moment, claim precedence over the nation's first need, which is, in every walk of life, to get on with its work with the minimum of interference at home and of disturbance abroad.

- Election manifesto (4 November 1922), quoted in Robert Blake, The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858–1923 (1955), p. 466

- I think, perhaps, it would be useful if I repeat again to you the words which I used in the first speech when I became leader of our party [in 1911]...“No government of which I am a member will ever be a government of reaction...” That was my view then and it is my view today, and if I thought the Unionist Party was or would ever become a party of that kind I would not be a member of it.

- Speech in the Public Baths, Old Kent Road (7 November 1922), quoted in The Times (8 November 1922), p. 14

Quotes about Bonar Law

edit- There was a vast new electorate in this country; a new democracy had been called into being by the last Reform Bill. There were millions of voters unattached to any party, and up and down the country people were wondering exactly what they wanted and for whom they could vote. One morning they opened their newspapers and read that Mr. Lloyd George said that Mr. Bonar Law is honest to the verge of simplicity. The British people said, "By God, that is what we have been looking for."

- Stanley Baldwin, speech in Oxford (8 June 1923), quoted in The Times (9 June 1923), p. 12

- I know that Bonar Law was the greatest figure on the political stage with which these books deal—that by action, by support, or by withdrawal, he made and unmade every Government from 1915 to 1922. And I can prove it—but there are some people whom I never expect to admit it or believe it.

- Lord Beaverbrook, Politicians and the War, 1914–1916, Vol. II (1932), quoted in The Times (13 May 1932), p. 8

- We had never known a more selfless man, a more loyal man; selfless, but also in a peculiar way ambitious. Strangely enough, when everything had come to him he appeared to regard it as dead ashes. There was no joy in the achievement. I think something snapped when the news came that his son had fallen in the war. Then there were the warning beginnings of his illness.

- Sir Robert Bruce, Greystones: Musings Without Dates (1932), p. 43

- By an overwhelming vote the Conservative Party determined to break with Lloyd George and end the National Coalition Government. The Prime Minister resigned that same afternoon. In the morning we had been friends and colleagues of all of these people. By nightfall they were our party foes, intent on driving us from public life. With the solitary and unexpected exception of Lord Curzon, all the prominent Conservatives who had fought the war with us, and the majority of all the Ministers, adhered to Lloyd George. These included Arthur Balfour, Austen Chamberlain, Robert Horne, and Lord Birkenhead, the four ablest figures in the Conservative Party. At the crucial moment I was prostrated by a severe operation for appendicitis, and in the morning when I recovered consciousness I learned that the Lloyd George government had resigned, and that I had lost not only my appendix but my office as Secretary of State for the Dominions and Colonies, in which I conceived myself to have had some Parliamentary and administrative success. Mr. Bonar Law, who had left us a year before for serious reasons of health, reluctantly became Prime Minister. He formed a Government of what one might call "the Second Eleven". Mr. Baldwin, the outstanding figure, was Chancellor of the Exchequer. The Prime Minister asked the King for a Dissolution. The people wanted a change. Mr. Bonar Law, with Mr. Baldwin at his side, and Lord Beaverbrook as his principal stimulant and mentor, gained a majority of seventy-three, with all the expectation of a five-year tenure of power. Early in the year 1923 Mr. Bonar Law resigned the Premiership and retired to die of his fell affliction. Mr. Baldwin succeeded him as Prime Minister, and Lord Curzon reconciled himself to the office of Foreign Secretary in the new administration.

- Winston Churchill, The Second World War Volume 1: The Gathering Storm (1948), p. 19, ISBN 0-395-41055-x

- His delivery was extraordinarily good and, though he spoke for an hour and a half I should think, his voice never failed him and every word was clear – and bold. It wasn't brilliant oratory, no flowers of rhetoric à la Curzon, or subtle 'nuances' à la Balfour, but it was good hard sound commonsense. ... He held his audience all through his speech, you felt he was in touch and in sympathy with them and they with him. He was so extraordinarily quiet and self-possessed, it was almost as if he were chatting to us confidentially about it all instead of making an elaborate speech.

- Lady Dawkins to Lord Milner (27 January 1912), quoted in John Ramsden, A History of the Conservative Party: The Age of Balfour and Baldwin, 1902–1940 (1978), p. 91

- Mr. Bonar Law once told me that he had read Gibbon's "Decline and Fall" three times before he was 21. He added in his simple, whimsical way, "I think it must have been from ambition. I liked to read of common soldiers becoming emperors." On another occasion he informed me that only two political causes had ever excited him in any powerful interest, Ulster and Protection.

- H. A. L. Fisher, letter to The Times (4 March 1932), p. 15

- Mr. Bonar Law told me that he was finally convinced of the necessity of the continuation of the Coalition Government under Mr. Lloyd George's leadership by the following incident:—The two British statesmen were returning from Paris on the evening of the day upon which it became practically certain that the Germans would sign the Armistice. The revulsion of feeling after the terrible strain of the War was naturally very great. Mr. Bonar Law sank back into the corner of the railway carriage, feeling that he never wished to do another stroke of work and that for the moment at least he must be allowed to sleep. All the way to the Channel the Prime Minister kept pouring out ideas for the reconstruction of England with a prodigality of resource and invention which the exertions of the War had in no wise abated. "By the end of the journey," Mr. Bonar Law said, "I had made up my mind that L. G. was the only man to govern the country."

- H. A. L. Fisher, letter to The Times (4 March 1932), p. 15

- He became Prime Minister of England for the simple and satisfying reason that he was not Mr. Lloyd George. At an open competition in the somewhat negative exercise of not being Mr. Lloyd George that was held in November 1922, Mr. Law was found to be more indubitably not Mr. Lloyd George than any of the other competitors; and in consequence, by the mysterious operation of the British Constitution, he reigned in his stead.

- Philip Guedalla, A Gallery (1924), p. 134

- The Scottish-Canadian Bonar Law had succeeded Arthur Balfour as Tory standard-bearer in November 1911, and played the Ulster 'Orange card' as a cynical gambit against the Liberals. On 28 November 1913, the leader of 'His Majesty's Loyal Opposition' publicly appealed to the British Army not to enforce Home Rule in northern Ireland. This was a staggering piece of constitutional impropriety, which nonetheless commanded the support of his party and most of the aristocracy, while not provoking the censure of the King.

- Max Hastings, Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War (2014), ISBN 978-0-307-74383-1

- Mr Bonar Law was Prime Minister. He was one of the greatest men ever I met, very able and very sincere. He was a true House of Commons man. On one occasion we were in a hot debate. I sat for seven hours without leaving my seat. Bonar Law was there all the time. He was looking ill and languid. Then he rose to reply. Without a note, he took up and answered seven speeches in detail. I could not believe my ears and eyes. He spoke as if he had the speeches in front of him. A week later we interrupted business for two hours with a constant barracking: “What are you going to do about unemployment?” It was a violent attack. We won some concessions. Bonar Law showed no resentment. He remained calm and unruffled. Afterwards we happened to meet face to face in the Lobby. He stopped and said: “You Clyde boys were pretty hard on me today. But it's fine to hear your Glasgow accent. It's like a sniff of the air of Scotland in the musty atmosphere of this place.” What could a man do in the face of such a greeting?

- David Kirkwood, My Life of Revolt (1935), pp. 201–202

- The Conservatives have done a wise thing for once. They have selected the very best man – the only man. He is a clever fellow and has a nice disposition, and I like him very much. He has a good brain.

- David Lloyd George's remarks to George Riddell, as recorded in Riddell's diary (late November 1911), quoted in The Riddell Diaries 1908–1923, ed. J. M. McEwen (1986), p. 27

- The public have never realised the creative common-sense of Bonar Law—he was the most constructive objector that I have ever known.

- David Lloyd George's remarks to Harold Nicolson, as recorded in Nicolson's diary (6 July 1936), quoted in Harold Nicolson, Diaries and Letters, 1930-1939, ed. Nigel Nicolson (1966), p. 268

- Those of us who were privileged to enjoy his personal friendship knew that he never ceased to acknowledge the debt he owed to his Scottish ancestry and his Glasgow training, and I well remember, when he was elected Lord Rector of Glasgow University and received the Freedom of the City of Glasgow, he acknowledged in a noble exordium his obligations to what he regarded as his native city.

- John Smith Samuel, letter to The Times (10 March 1932), p. 8

- No harder man has risen to the top in British political life.

- A. J. P. Taylor, 'Iron Merchant', The Observer (9 October 1955), p. 10

- The most remarkable personality it has been my good fortune to meet. He was the greatest gentleman I have ever met in Parliament or without.

- Ben Tillett, Memories and Reflections (1931), quoted in Egon Jameson, 10 Downing Street: The Romance of a House (1946), p. 525