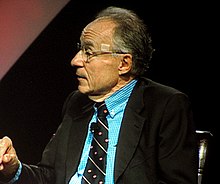

Arno Allan Penzias

German-born American physicist

Arno Allan Penzias (26 April 1933 – 22 January 2024) was an American physicist and radio astronomer. Along with Robert Woodrow Wilson, he discovered the cosmic microwave background radiation, for which he shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1978.

Quotes

edit- A closed universe, one that explodes, expands, falls back on itself and explodes again, repeating the process over and over eternally, that would be a pointless universe. … But it seems to me that the data we have in hand right now clearly show that there is not nearly enough matter in the universe, not enough by a factor of three, for the universe to be able to fall back on itself ever again.

My argument, is that the best data we have are exactly what I would have predicted, had I had nothing to go on but the five books of Moses, the Psalms, the Bible as a whole.- As quoted in "Clues to Universe Origin Expected" by Malcolm W. Browne, in The New York Times (12 March 1978); the final sentence of this statement is often applied out of context, as if Penzias were referring to all data of all scientific research as a whole, rather than narrowly, as to specific theories on whether we exist within an "open" or "closed" universe.

- The Bible talks of purposeful creation. What we have, however, is an amazing amount of order; and when we see order, in our experience it normally reflects purpose.

- As quoted in The Voice of Genius : Conversations with Nobel Scientists and Other Luminaries (1995) by Denis Brian

- Well, if we read the Bible as a whole we would expect order in the world. Purpose would imply order, and what we actually find is order.

- As quoted in The Voice of Genius : Conversations with Nobel Scientists and Other Luminaries (1995) by Denis Brian

- Astronomy leads us to an unique event, a universe which was created out of nothing and delicately balanced to provide exactly the conditions required to support life. In the absence of an absurdly-improbable accident, the observations of modern science seem to suggest an underlying, one might say, supernatural plan.

Autobiographical notes (2005)

edit- I was born in Munich, Germany, in 1933. I spent the first six years of my life comfortably, as an adored child in a closely-knit middle-class family. Even when my family was rounded up for deportation to Poland it didn’t occur to me that anything could happen to us. All I remember is scrambling up and down three tiers of narrow beds attached to the walls of a very large room, and then taking a long train trip. After some days of back and forth on the train, we were returned to Munich. All the grown-ups were happy and relieved, but I began to realize that there were bad things that my parents couldn’t completely control, something to do with being Jewish. I learned that everything would be fine if we could only get to “America”.

- It was taken for granted that I would go to college, studying science, presumably chemistry, the only science we knew much about. “College” meant City College of New York, a municipally-supported institution then beginning its second century of moving the children of New York’s immigrant poor into the American middle class. I discovered physics in my freshman year and switched my “major” from chemical engineering to physics. Graduation, marriage and two years in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, saw me applying to Columbia University in the Fall of 1956.

- After a painful but largely successful struggle with courses and qualifying exams, I began my thesis work under Professor Townes. I was given the task of building a maser amplifier in a radio-astronomy experiment of my choosing; the equipment-building went better than the observations.

In 1961, with my PhD thesis complete, I went in search of a temporary job at Bell Laboratories, Holmdel, New Jersey. Their unique facilities made it an ideal place to finish the observations I had begun during my thesis work. “Why not take a permanent job? You can always quit,” was the advice of Rudi Kompfner, then Director of the Radio Research Laboratory. I took his advice, and remained a Bell Labs employee for the next thirty seven years.

Since the large horn antenna I had planned to use for radio-astronomy was still engaged in the ECHO satellite project for which it was originally constructed, I looked for something interesting to do with a smaller fixed antenna. The project I hit upon was a search for line emission from the then still undetected interstellar OH molecule. While the first detection of this molecule was made by another group, I learned quite a bit from the experience.

- Millimeter-wave spectral studies have proven to be a particularly fruitful area for radio astronomy, and are the subject of active and growing interest, involving a large number of scientists around the world. The most personally satisfying portion of this work for me was using molecular spectra to explore the isotopic composition of interstellar atoms — thereby tracing the nuclear processes that produced them. Most notably our 1973 discovery of DCN, the first deuterated molecular species found in interstellar space, enabled me to trace the distribution of deuterium in the galaxy. This work provided us with evidence for the cosmological origin of this unique element, which had earned the nickname “Arno’s white whale”. Of all the nuclear species found in nature, deuterium is the only one whose origin stems exclusively from the explosive origin of the Universe. Because deuterium’s cosmic abundance serves as the single most sensitive parameter in the prediction of cosmic background radiation, these measurements provided strong support for the “Big Bang” interpretation of our earlier discovery.

- In retrospect, the research organization which emerged from the decade following the Bell System’s breakup deployed a far richer set of capabilities than its predecessor. In particular, our work featured a growing software component, even as we strove to improve our hardware capabilities in areas such as light-wave and electronics. The marketplace upheaval brought forth by increased competition helped speed the pace of technological revolution, and forced change upon the research and development institutions of all industrialized nations, Bell Labs included. While change is rarely comfortable, I am happy to say that we not only survived but also grew more capable in the process — seeding much of the information revolution which now pervades the world in which we live.

Except for two or three papers on interstellar isotopes, my tenure as Bell Labs’ Vice-President of Research brought my personal research in astrophysics to an end. In its place, I pursued my interest in the principles which underlie the creation and effective use of technology in our society, and eventually found time to write a book on the subject Ideas and Information, published by W.W. Norton in 1989. In essence, the book depicts computers as a wonderful tool for human beings but a dreadful role model for what we humans know as intelligence. In other words, “If you don’t want to be replaced by a machine, don’t try to act like one!”