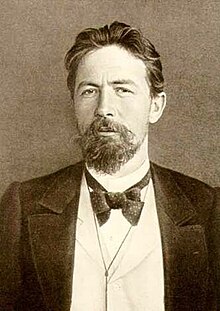

Anton Chekhov

Russian dramatist and author (1860–1904)

(Redirected from Anton Chekov)

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (Анто́н Па́влович Че́хов) (29 January 1860 – 15 July 1904) (Old Style: 17 January 1860 – 2 July 1904) was a Russian short story writer and playwright.

Quotes

edit- When a person is born, he can embark on only one of three roads of life: if you go right, the wolves will eat you; if you go left, you’ll eat the wolves; if you go straight, you’ll eat yourself.

- Fatherlessness or Platonov, Act I, sc. xiv (1878)

- That can not possibly be, because it could never possibly be.

- Letter to a Learned Neighbor (1880)

- Eyes—the head’s chief of police. They watch and make mental notes. A blind person is like a city abandoned by the authorities. On sad days they cry. In these carefree times they weep only from tender emotions.

- A Brief Human Anatomy (1883)

- We live not in order to eat, but in order not to know what we feel like eating.

- The Fruits of Long Meditations (1884)

- Better a debauched canary than a pious wolf.

- Innocuous Thoughts (1885)

- If only one tooth aches, rejoice that not all of them ache.... If your wife betrays you, be glad that she betrayed only you and not the nation.

- Life is Wonderful (For those attempting suicide) (1885)

- Love is a scandal of the personal sort.

- The Piano Player (1885)

- Once you’ve married, be strict but just with your wife, don’t allow her to forget herself, and when a misunderstanding arises, say: “Don’t forget that I made you happy.”

- Guide for Those Wishing to Marry (1885)

- By nature servile, people attempt at first glance to find signs of good breeding in the appearance of those who occupy more exalted stations.

- A Futile Occurrence or A Trivial Incident (1886)

- Watching a woman make Russian pancakes, you might think that she was calling on the spirits or extracting from the batter the philosopher’s stone.

- Russian Pancakes or Bliny (1886)

- A fiancé is neither this nor that: he’s left one shore, but not yet reached the other.

- Love (1886)

- Only during hard times do people come to understand how difficult it is to be master of their feelings and thoughts.

- Misfortune (1886)

- I myself smoke, but my wife asked me to speak today on the harmfulness of tobacco, so what can I do? If it’s tobacco, then let it be tobacco.

- On the Harmfulness of Tobacco (1886)

- The thirst for powerful sensations takes the upper hand both over fear and over compassion for the grief of others.

- An Evil Night (1886)

- Probably nature itself gave man the ability to lie so that in difficult and tense moments he could protect his nest, just as do the vixen and wild duck.

- Difficult People (1886)

- Faith is an aptitude of the spirit. It is, in fact, a talent: you must be born with it.

- On the Road (1886)

- It is depressing to hear the unfortunate or dying man jest.

- On the Road

- Silence accompanies the most significant expressions of happiness and unhappiness: those in love understand one another best when silent, while the most heated and impassioned speech at a graveside touches only outsiders, but seems cold and inconsequential to the widow and children of the deceased.

- Enemies (1887)

- Несчастные эгоистичны, злы, несправедливы, жестоки и менее, чем глупцы, способны понимать друг друга. Не соединяет, а разъединяет людей несчастье...

- The unhappy are egotistical, base, unjust, cruel, and even less capable of understanding one another than are idiots. Unhappiness does not unite people, but separates them...

- Enemies

- [Ognev] recalled endless, heated, purely Russian arguments, when the wranglers, spraying spittle and banging their fists on the table, fail to understand yet interrupt one another, themselves not even noticing it, contradict themselves with every phrase, change the subject, then, having argued for two or three hours, begin to laugh.

- Verotchka (1887)

- Not everyone knows when to be silent and when to go. It not infrequently happens that even diplomatic persons of good worldly breeding fail to observe that their presence is arousing a feeling akin to hatred in their exhausted or busy host, and that this feeling is being concealed with an effort and disguised with a lie.

- The Letter (1887)

- Each of us is full of too many wheels, screws and valves to permit us to judge one another on a first impression or by two or three external signs.

- Ivanov, Act III, sc. vi (1887)

- Country acquaintances are charming only in the country and only in the summer. In the city in winter they lose half of their appeal.

- The Story of Mme. NN or Lady N—'s Story or A Lady's Story (1887)

- One can prove or refute anything at all with words. Soon people will perfect language technology to such an extent that they’ll be proving with mathematical precision that twice two is seven.

- Lights (1888)

- You look at any poetic creature: muslin, ether, demigoddess, millions of delights; then you look into the soul and find the most ordinary crocodile!

- The Bear or The Boor, sc. viii (1888)

- If you can’t distinguish people from lap-dogs, you shouldn’t undertake philanthropic work.

- The Princess (1889)

- The sea has neither meaning nor pity.

- Gusev (1890)

- Everyone has the same God; only people differ.

- The Duel (1891)

- It is not only the prisoners who grow coarse and hardened from corporeal punishment, but those as well who perpetrate the act or are present to witness it.

- A Journey to Sakhalin (1891)

- No matter how corrupt and unjust a convict may be, he loves fairness more than anything else. If the people placed over him are unfair, from year to year he lapses into an embittered state characterized by an extreme lack of faith.

- A Journey to Sakhalin

- There is something beautiful, touching and poetic when one person loves more than the other, and the other is indifferent.

- After the Theatre (1892)

- To regard one’s immortality as an exchange of matter is as strange as predicting the future of a violin case once the expensive violin it held has broken and lost its worth.

- Ward No. 6, ch. 7 (1892)

- Life is a vexatious trap; when a thinking man reaches maturity and attains to full consciousness he cannot help feeling that he is in a trap from which there is no escape.

- Ward No. 6

- It’s even pleasant to be sick when you know that there are people who await your recovery as they might await a holiday.

- The Story of an Unknown Man or An Anonymous Story, ch. 15 (1893)

- There is nothing more awful, insulting, and depressing than banality.

- The Teacher of Literature (1894)

- Pesotsky had an immense house with columns and lions, off which the stucco was peeling, and with a footman in swallow-tails at the entrance. The old park, laid out in the English style, gloomy and severe, stretched for almost three-quarters of a mile to the river, and there ended in a steep, precipitous clay bank, where pines grew with bare roots that looked like shaggy paws; the water shone below with an unfriendly gleam, and the peewits flew up with a plaintive cry, and there one always felt that one must sit down and write a ballad.

- The Black Monk (1894)

- Death can only be profitable: there’s no need to eat, drink, pay taxes, offend people, and since a person lies in a grave for hundreds or thousands of years, if you count it up the profit turns out to be enormous.

- Rothschild’s Fiddle (1894)

- Moscow is a city that has much suffering ahead of it.

- Three Years (1895)

- By poeticizing love, we imagine in those we love virtues that they often do not possess; this then becomes the source of constant mistakes and constant distress.

- Ariadne (1895)

- Good breeding doesn't mean that you won't spill sauce on the tablecloth, but that you won't notice when someone else does.

- The House with the Mezzanine (1896)

- It seems to me that all of the evil in life comes from idleness, boredom, and psychic emptiness, but all of that is inevitable when you become accustomed to living at others’ expense.

- My Life (1896)

- Exquisite nature, daydreams, and music say one thing, real life another.

- In a Native Corner or At Home (1897)

- All of life and human relations have become so incomprehensibly complex that, when you think about it, it becomes terrifying and your heart stands still.

- In the Cart or A Journey by Cart or The Schoolmistress (1897)

- Who keeps the tavern and serves up the drinks? The peasant. Who squanders and drinks up money belonging to the peasant commune, the school, the church? The peasant. Who would steal from his neighbor, commit arson, and falsely denounce another for a bottle of vodka? The peasant.

- Peasants (1897)

- While you’re playing cards with a regular guy or having a bite to eat with him, he seems a peaceable, good-humoured and not entirely dense person. But just begin a conversation with him about something inedible, politics or science, for instance, and he ends up in a deadend or starts in on such an obtuse and base philosophy that you can only wave your hand and leave.

- Ionych (1898)

- There are no small number of people in this world who, solitary by nature, always try to go back into their shell like a hermit crab or a snail.

- The Man in a Case (1898)

- People who live alone always have something on their minds that they would willingly share.

- About Love (1898)

- It is uncomfortable to ask condemned people about their sentences just as it is awkward to ask wealthy people why they need so much money, why they use their wealth so poorly, and why they don’t just get rid of it when they recognize that it is the cause of their unhappiness.

- Episode from a Practice or A Doctor's Visit (1898)

- Nature’s law says that the strong must prevent the weak from living, but only in a newspaper article or textbook can this be packaged into a comprehensible thought. In the soup of everyday life, in the mixture of minutia from which human relations are woven, it is not a law. It is a logical incongruity when both strong and weak fall victim to their mutual relations, unconsciously subservient to some unknown guiding power that stands outside of life, irrelevant to man.

- Episode from a Practice

- If you really think about it, everything is wonderful in this world, everything except for our thoughts and deeds when we forget about the loftier goals of existence, about our human dignity.

- The Lady with the Dog (1899)

- She read a lot, wrote letters without the letter ъ, …

- Она много читала, не писала въ письмахъ ъ, …

- The Lady with the Dog

- Dear, sweet, unforgettable childhood! Why does this irrevocable time, forever departed, seem brighter, more festive and richer than it actually was?

- The Bishop (1902)

- Thought and beauty, like a hurricane or waves, should not know conventional, delimited forms.

- Мысль и красота, подобно урагану и волнам, не должны знать привычных, определенных форм.

- A Letter (uncertain date, story not published by Chekhov)

- If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired. Otherwise don't put it there."

- Ilia Gurliand Reminiscences of A. P. Chekhov, in Театр и искусство (Teatr i Iskusstvo, literally: Theater and art review) 1904, No 28, 11 July, p. 521. commonly known as Chekhov's dictum or Chekhov's gun.

Note-Book of Anton Chekhov (1921)

edit- [http://www.gutenberg.org/files/12494/ Translated S. S. Koteliansky and Leonard Woolf

- Between "there is a God" and "there is no God" lies a whole vast tract, which the really wise man crosses with great effort. A Russian knows one or other of these two extremes, and the middle tract between them does not interest him; and therefore he usually knows nothing, or very little. (Diary, 1897)

- Dinner at the "Continental" to commemorate the great reform [the abolition of the serfdom in 1861]. Tedious and incongruous. To dine, drink champagne, make a racket, and deliver speeches about national consciousness, the conscience of the people, freedom, and such things, while slaves in tail-coats are running round your tables, veritable serfs, and your coachmen wait outside in the street, in the bitter cold—that is lying to the Holy Ghost. (Diary, 9 February 1897)

- Mankind has conceived history as a series of battles; hitherto it has considered fighting as the main thing in life.

- The desire to serve the common good must without fail be a requisite of the soul, a necessity for personal happiness; if it issues not from there, but from theoretical or other considerations, it is not at all the same thing.

- Solomon made a great mistake when he asked for wisdom.

- Ordinary hypocrites pretend to be doves; political and literary hypocrites pretend to be eagles. But don't be disconcerted by their aquiline appearance. They are not eagles, but rats or dogs.

- It always seems to the brothers and the father that their brother or son didn't marry the right person.

- Love is a great thing. It is not by chance that in all times and practically among all cultured peoples love in the general sense and the love of a man for his wife are both called love. If love is often cruel or destructive, the reason lies not in love itself, but in the inequality between people.

- A nice man would feel ashamed even before a dog.

- There is no national science, just as there is no national multiplication table; what is national is no longer science.

- How pleasant it is to respect people! When I see books, I am not concerned with how the authors loved or played cards; I see only their marvelous works.

- Какое наслаждение уважать людей! Когда я вижу книги, мне нет дела до того, как авторы любили, играли в карты, я вижу только их изумительные дела.

- I observed that after marriage people cease to be curious.

- The more refined the more unhappy.

- Alernate translation: The more cultured a man, the less fortunate he is.

- Чем культурнее, тем несчастнее.

- People love talking of their diseases, although they are the most uninteresting things in their lives.

- Love, friendship, respect, do not unite people as much as a common hatred for something.

- Alternate translation: Nothing better forges a bond of love, friendship or respect than common hatred toward something.

- Also quoted in Psychologically Speaking: A Book of Quotations, Kevin Connolly and Margaret Martlew, 1999, p. 96

- It is easier to ask of the poor than of the rich.

- Death is terrible, but still more terrible is the feeling that you might live for ever and never die.

- They say: "In the long run truth will triumph;" but it is untrue.

- When an actor has money, he doesn't send letters but telegrams.

- Better to perish from fools than to accept praises from them.

- If you are afraid of loneliness, do not marry.

- Although you may tell lies, people will believe you, if only you speak with authority.

- As I shall lie in the grave alone, so in fact I live alone.

- Our self-esteem and conceit are European, but our culture and actions are Asiatic.

- Man will only become better when you make him see what he is like.

- Alternate translation: Man will become better when you show him what he is like.

- Тогда человек станет лучше, когда вы покажете ему, каков он есть…

- How intolerable people are sometimes who are happy and successful in everything.

- When one longs for a drink, it seems as though one could drink a whole ocean—that is faith; but when one begins to drink, one can only drink altogether two glasses—that is science.

- If you wish women to love you, be original; I know a man who used to wear felt boots summer and winter, and women fell in love with him.

- We fret ourselves to reform life, in order that posterity may be happy, and posterity will say as usual: "In the past it used to be better, the present is worse than the past."

- Alternate translation: We go to great pains to alter life for the happiness of our descendants and our descendants will say as usual: things used to be so much better, life today is worse than it used to be.

- Мы хлопочем, чтобы изменить жизнь, чтобы потомки были счастливы, а потомки скажут по обыкновению: прежде лучше было, теперешняя жизнь хуже прежней.

- Nothing lulls and inebriates like money; when you have a lot, the world seems a better place than it actually is.

- Ничто так не усыпляет и не опьяняет, как деньги; когда их много, то мир кажется лучше, чем он есть.

- There is not a single criterion which can serve as the measure of the non-existent, of the non-human.

- Alternate translation: Not one of our mortal gauges is suitable for evaluating non-existence, for making judgments about that which is not a person.

- Ни одна наша смертная мерка не годится для суждения о небытии, о том, что не есть человек.

- And I thought that were we now to obtain political liberty, of which we talk so much, while engaged in biting one another, we should not know what to do with it, we should waste it in accusing one another in the newspapers of being spies and money-grubbers, we should frighten society with the assurance that we have neither men, nor science, nor literature, nothing! Nothing!

- It is unfortunate that we try to solve the simplest questions cleverly, and therefore make them unusually complicated. We should seek a simple solution.

- There is no Monday which will not give its place to Tuesday.

Letters

edit- My mother and father are the only people on the whole planet for whom I will never begrudge a thing. Should I achieve great things, it is the work of their hands; they are splendid people and their absolute love of their children places them above the highest praise. It cloaks all of their shortcomings, shortcomings that may have resulted from a difficult life.

- Letter to his cousin, M.M. Chekhov (July 29, 1877)

- Do you know when you may concede your insignificance? In front of God or, perhaps, in front of the intellect, beauty, or nature, but not in front of people. Among people, one must be conscious of one’s dignity.

- Ничтожество свое сознавай, знаешь где? Перед богом, пожалуй, пред умом, красотой, природой, но не пред людьми. Среди людей нужно сознавать свое достоинство.

- Letter to his brother, M.P. Chekhov (April 1879)

- A grimy fly can soil the entire wall and a small, dirty little act can ruin the entire proceedings.

- Letter to A.N. Kanaev (March 26, 1883)

- In order to cultivate yourself and to drop no lower than the level of the milieu in which you have landed, it is not enough to read Pickwick and memorize a monologue from Faust. <…> You need to work continually day and night, to read ceaselessly, to study, to exercise your will… Each hour is precious.

- Чтобы воспитаться и не стоять ниже уровня среды, в которую попал, недостаточно прочесть только Пикквика и вызубрить монолог из «Фауста». <…> Тут нужны беспрерывный дневной и ночной труд, вечное чтение, штудировка, воля… Тут дорог каждый час…

- Letter to his brother, N.P. Chekhov (March 1886)

- Isolation in creative work is an onerous thing. Better to have negative criticism than nothing at all.

- Одиночество в творчестве тяжелая штука. Лучше плохая критика, чем ничего…

- Letter to his brother, A.P. Chekhov (May 10, 1886)

- When in a serious mood, it seems to me that those people are illogical who feel an aversion toward death. As far as I can see, life consists exclusively of horrors, unpleasantnesses and banalities, now merging, now alternating.

- Letter to M.V. Kiseleva (September 29, 1886)

- To describe drunkenness for the colorful vocabulary is rather cynical. There is nothing easier than to capitalize on drunkards.

- Letter to N.A. Leikin (December 24, 1886)

- There are people whom even children’s literature would corrupt. They read with particular enjoyment the piquant passages in the Psalter and in the Wisdom of Solomon.

- Letter to M.V. Kiseleva (January 14, 1887)

- Despite your best efforts, you could not invent a better police force for literature than criticism and the author’s own conscience.

- Letter to M.V. Kiseleva (January 14, 1887

- Oh, what women are here!

- Ах, какие здесь женщины!

- Letter to N. A. Leykin (April 7, 1887)

- Tell me, pleez, my sawl, when will I live in human way, that is, to work and not to be in need? Now I work, and I'm in need, and I spoil my reputation by the need to write bullshit.

- Скажи, пожалюста, душя моя, когда я буду жить по-человечески, т. е. работать и не нуждаться? Теперь я и работаю, и нуждаюсь, и порчу свою репутацию необходимостью работать херовое.

- Letter to the Alexander Chekhov (April 14, 1887)

- I was so drunk the whole time that I took bottles for girls and girls for bottles.

- Letter to the Chekhov family (April 25, 1887)

- Writers are as jealous as pigeons.

- Letter to I.L. Leontev (February 4, 1888)

- In Western Europe people perish from the congestion and stifling closeness, but with us it is from the spaciousness.... The expanses are so great that the little man hasn’t the resources to orient himself.... This is what I think about Russian suicides.

- Letter to D.V. Grigorovich (February 5, 1888)

- Happiness does not await us all. One needn’t be a prophet to say that there will be more grief and pain than serenity and money. That is why we must hang on to one another.

- Letter to K.S. Barantsevich (March 3, 1888)

- Tsars and slaves, the intelligent and the obtuse, publicans and pharisees all have an identical legal and moral right to honor the memory of the deceased as they see fit, without regard for anyone else’s opinion and without the fear of hindering one another.

- Letter to K.S. Barantsevich (March 30, 1888)

- Hypocrisy is a revolting, psychopathic state.

- Letter to I.L. Leontev (August 29, 1888)

- One must speak about serious things seriously.

- Letter to A.N. Pleshcheev (September 9, 1888)

- I feel more confident and more satisfied when I reflect that I have two professions and not one. Medicine is my lawful wife and literature is my mistress. When I get tired of one I spend the night with the other. Though it's disorderly it's not so dull, and besides, neither really loses anything, through my infidelity.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (September 11, 1888)

- I don’t know why one can’t chase two rabbits at the same time, even in the literal sense of those words. If you have the hounds, go ahead and pursue.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (September 11, 1888)

- The more simply we look at ticklish questions, the more placid will be our lives and relationships.

- Letter to his brother, A.P. Chekhov (September 24, 1888)

- I would like to be a free artist and nothing else, and I regret God has not given me the strength to be one.

- Letter to Alexei Pleshcheev (October 4, 1888)

- My holy of holies is the human body, health, intelligence, talent, inspiration, love, and the most absolute freedom imaginable, freedom from violence and lies, no matter what form the latter two take. Such is the program I would adhere to if I were a major artist.

- Letter to Alexei Pleshcheev (October 4, 1888)

- Pharisaism, obtuseness and tyranny reign not only in the homes of merchants and in jails; I see it in science, in literature, and among youth. I consider any emblem or label a prejudice.... My holy of holies is the human body, health, intellect, talent, inspiration, love and the most absolute of freedoms, the freedom from force and falsity in whatever forms they might appear.

- Letter to Alexei Pleshcheev (October 4, 1888)

- Lying is the same as alcoholism. Liars prevaricate even on their deathbeds.

- Letter to A.N. Pleshcheev (October 9, 1888)

- There should be more sincerity and heart in human relations, more silence and simplicity in our interactions. Be rude when you’re angry, laugh when something is funny, and answer when you’re asked.

- Letter to his brother, A.P. Chekhov (October 13, 1888)

- A tree is beautiful, but what’s more, it has a right to life; like water, the sun and the stars, it is essential. Life on earth is inconceivable without trees. Forests create climate, climate influences peoples’ character, and so on and so forth. There can be neither civilization nor happiness if forests crash down under the axe, if the climate is harsh and severe, if people are also harsh and severe.... What a terrible future!

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (October 18, 1888)

- He who doesn’t know how to be a servant should never be allowed to be a master; the interests of public life are alien to anyone who is unable to enjoy others’ successes, and such a person should never be entrusted with public affairs.

- Letter to A.N. Pleshcheev (October 25, 1888)

- An artist must pass judgment only on what he understands; his range is limited as that of any other specialist—that's what I keep repeating and insisting upon. Anyone who says that the artist's field is all answers and no questions has never done any writing or had any dealings with imagery. An artist observes, selects, guesses and synthesizes.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (October 27, 1888)

- It is a poor thing for the writer to take on that which he doesn’t understand.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (October 27, 1888)

- You are right to demand that an artist engage his work consciously, but you confuse two different things: solving the problem and correctly posing the question.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (October 27, 1888)

- I have in my head a whole army of people pleading to be let out and awaiting my commands.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (October 27, 1888)

- I don’t care for success. The ideas sitting in my head are annoyed by, and envious of, that which I’ve already written.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (October 27, 1888)

- We learn about life not from pluses alone, but from minuses as well.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (December 23, 1888)

- It doesn’t matter that your painting is small. Kopecks are also small, but when a lot are put together they make a ruble. Each painting displayed in a gallery and each good book that makes it into a library, no matter how small they may be, serve a great cause: accretion of the national wealth.

- Letter to S.P. Kuvshinnikova (December 25, 1888)

- Children are holy and pure. Even those of bandits and crocodiles belong among the angels.... They must not be turned into a plaything of one’s mood, first to be tenderly kissed, then rabidly stomped at.

- Letter to his brother, A.P. Chekhov (January 2, 1889)

- Of course politics is an interesting and engrossing thing. It offers no immutable laws, nearly always prevaricates, but as far as blather and sharpening the mind go, it provides inexhaustible material.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (January 4, 1889)

- In one-act pieces there should be only rubbish—that is their strength.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (January 6, 1889)

- Narrative prose is a legal wife, while drama is a posturing, boisterous, cheeky and wearisome mistress.

- Letter to A.N. Pleshcheev (January 15, 1889)

- Everything is good in due measure and strong sensations know not measure.

- Letter to N.M. Lintvareva (February 11, 1889)

- Lermontov died at age twenty-eight and wrote more than have you and I put together. Talent is recognizable not only by quality, but also by the quantity it yields.

- Лермонтов умер 28 лет, а написал больше, чем оба мы с тобой вместе. Талант познается не только по качеству, но и по количеству им сделанного

- Letter to P.A. Sergeenko (March 6, 1889)

- Neither I nor anyone else knows what a standard is. We all recognize a dishonorable act, but have no idea what honor is.

- Letter to A.N. Pleshcheev (April 9, 1889)

- Brevity is the sister of talent.

- Краткость — сестра таланта.

- Letter to Alexander P. Chekhov (April 11, 1889)

- Everyone judges plays as if they were very easy to write. They don’t know that it is hard to write a good play, and twice as hard and tortuous to write a bad one.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (May 4, 1889)

- When performing an autopsy, even the most inveterate spiritualist would have to question where the soul is.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (May 7, 1889)

- Beware of exquisite language. The language should be simple and elegant.

- Берегись изысканного языка. Язык должен быть прост и изящен.

- Letter to Alexander P. Chekhov (May 8, 1889)

- Life is difficult for those who have the daring to first set out on an unknown road. The avant-garde always has a bad time of it.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (May 14, 1889)

- When a person doesn’t understand something, he feels internal discord: however he doesn’t search for that discord in himself, as he should, but searches outside of himself. Thence a war develops with that which he doesn’t understand.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (May 15, 1889)

- Without a knowledge of languages you feel as if you don’t have a passport.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (November 1889)

- Wherever there is degeneration and apathy, there also is sexual perversion, cold depravity, miscarriage, premature old age, grumbling youth, there is a decline in the arts, indifference to science, and injustice in all its forms.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (December 27, 1889)

- I drank so much in Peter<sburg> that Russia should be proud of me!

- …в Питере я выпил столько, что мною должна гордиться Россия!

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (February 20, 1890)

- In general, Russia suffers from a frightening poverty in the sphere of facts and a frightening wealth of all types of arguments.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (February 23, 1890)

- There are no lower or higher or median moralities. There is only one morality, and it is precisely the one that was given to us during the time of Jesus Christ and that stops me, you and Barantsevich from stealing, offending others, lying etc.

- Letter to I.L. Leontev (March 22, 1890)

- I divide all literary works into two categories: Those I like and those I don’t like. No other criterion exists for me.

- Letter to I.L. Leontev (March 22, 1890)

- One can only call that youth healthful which refuses to be reconciled to old ways and which, foolishly or shrewdly, combats the old. This is nature’s charge and all progress hinges upon it.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (March 29, 1890)

- The world is a fine place. The only thing wrong with it is us. How little justice and humility there is in us, how poorly we understand patriotism!

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (December 9, 1890)

- I think that it would be less difficult to live eternally than to be deprived of sleep throughout life.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (December 9, 1890)

- In my opinion it is harmful to place important things in the hands of philanthropy, which in Russia is marked by a chance character. Nor should important matters depend on leftovers, which are never there. I would prefer that the government treasury take care of it.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (December 17, 1890)

- One had better not rush, otherwise dung comes out rather than creative work.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (August 18, 1891)

- All great sages are as despotic as generals, and as ungracious and indelicate as generals, because they are confident of their impunity.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (September 8, 1891)

- He who constantly swims in the ocean loves dry land.

- Letter to E.M. Shavrova (September 16, 1891)

- We old bachelors smell like dogs, do we? So be it. But I must take issue with your claim that doctors who treat female illnesses are womanizers and cynics at heart. Gynecologists deal with savage prose the likes of which you have never dreamed of.

- Letter to E.M. Shavrova (September 16, 1891)

- Satiation, like any state of vitality, always contains a degree of impudence, and that impudence emerges first and foremost when the sated man instructs the hungry one.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (October 20, 1891)

- Can words such as Orthodox, Jew, or Catholic really express some sort of exclusive personal virtues or merits?

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (November 18, 1891)

- An expansive life, one not constrained by four walls, requires as well an expansive pocket.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (March 11, 1892)

- When we retreat to the country, we are hiding not from people, but from our pride, which, in the city and among people, operates unfairly and immoderately.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (March 17, 1892)

- People understand God as the expression of the most lofty morality. Maybe He needs only perfect people.

- Letter to E.M. Shavrova (April 6, 1892)

- The wealthy man is not he who has money, but he who has the means to live in the luxurious state of early spring.

- Letter to L.A. Avilova (April 29, 1892)

- There is nothing more vapid than a philistine petty bourgeois existence with its farthings, victuals, vacuous conversations, and useless conventional virtue.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (June 16, 1892)

- Despicable means used to achieve laudable goals render the goals themselves despicable.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (August 1, 1892)

- The more elevated a culture, the richer its language. The number of words and their combinations depends directly on a sum of conceptions and ideas; without the latter there can be no understandings, no definitions, and, as a result, no reason to enrich a language.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (October 12, 1892)

- The person who wants nothing, hopes for nothing, and fears nothing can never be an artist.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (November 25, 1892)

- Whoever sincerely believes that elevated and distant goals are as little use to man as a cow, that “all of our problems” come from such goals, is left to eat, drink, sleep, or, when he gets sick of that, to run up to a chest and smash his forehead on its corner.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (December 3, 1892)

- I abide by a rule concerning reviews: I will never ask, neither in writing nor in person, that a word be put in about my book.... One feels cleaner this way. When someone asks that his book be reviewed he risks running up against a vulgarity offensive to authorial sensibilities.

- Letter to N.M. Ezhov (March 22, 1893)

- When you live on cash, you understand the limits of the world around which you navigate each day. Credit leads into a desert with invisible boundaries.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (August 18, 1893)

- It’s easier to write about Socrates than about a young woman or a cook.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (January 2, 1894)

- Prudence and justice tell me that in electricity and steam there is more love for man than in chastity and abstinence from meat.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (March 27, 1894)

- The air of one’s native country is the most healthy air.

- Letter to his brother, G.M. Chekhov (January 1895)

- I would love to meet a philosopher like Nietzsche on a train or boat and to talk with him all night. Incidentally, I don’t consider his philosophy long-lived. It is not so much persuasive as full of bravura.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (February 25, 1895)

- I can’t accept “our nervous age,” since mankind has been nervous during every age. Whoever fears nervousness should turn into a sturgeon or smelt; if a sturgeon makes a stupid mistake, it can only be one: to end up on a hook, and then in a pan in a pastry shell.

- Letter to E.M. Savrova-Yust (February 28, 1895)

- Sports are positively essential. It is healthy to engage in sports, they are beautiful and liberal, liberal in the sense that nothing serves quite as well to integrate social classes, etc., than street or public games.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (March 16, 1895)

- By all means I will be married if you wish it. But on these conditions: everything must be as it has been hitherto—that is, she must live in Moscow while I live in the country, and I will come and see her. ... I promise to be an excellent husband, but give me a wife who, like the moon, will not appear every day in my sky.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (March 23, 1895)

- The bourgeoisie loves so-called “positive” types and novels with happy endings since they lull one into thinking that it is fine to simultaneously acquire capital and maintain one’s innocence, to be a beast and still be happy.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (April 13, 1895)

- A man who doesn’t drink is not, in my opinion, fully a man.

- Letter to N.A. Leikin (May 8, 1895)

- It’s worth living abroad to study up on genteel and delicate manners. The maid smiles continuously; she smiles like a duchess on a stage, while at the same time it is clear from her face that she is exhausted from overwork.

- Letter to I.P. Chekhov (October 2, 1897)

- Tell mother that however dogs and samovars might behave themselves, winter comes after summer, old age after youth, and misfortune follows happiness (or the other way around). A person can not be healthy and cheerful throughout life. Losses lie waiting and man can not safeguard against death, even if he be Alexander of Macedonia. One must be prepared for anything and consider everything to be inevitably essential, as sad as that may be.

- Letter to his sister Maria Pavlovna Chekhov (November 13, 1898)

- When a person expends the least amount of motion on one action, that is grace.

- Letter to Maxim Gorky (January 3, 1899)

- There are in life such confluences of circumstances that render the reproach that we are not Voltaires most inopportune.

- Letter to A.S. Suvorin (February 6, 1898)

- I have no faith in our hypocritical, false, hysterical, uneducated and lazy intelligentsia when they suffer and complain: their oppression comes from within. I believe in individual people. I see salvation in discrete individuals, intellectuals and peasants, strewn hither and yon throughout Russia. They have the strength, although there are few of them.

- Letter to I.I. Orlov (February 22, 1899)

- Women writers should write a lot if they want to write. Take the English women, for example. What amazing workers.

- Letter to L.A. Avilova (February 26, 1899)

- Is it our job to judge? The gendarme, policemen and bureaucrats have been especially prepared by fate for that job. Our job is to write, and only to write.

- Letter to L.A. Avilova (April 27, 1899)

- There are plenty of good people, but only a very, very few are precise and disciplined.

- Letter to V.A. Posse (February 15, 1900)

- You ask “What is life?” That is the same as asking “What is a carrot?” A carrot is a carrot and we know nothing more.

- Letter to his wife, Olga Knipper Chekhov (April 20, 1904)

A Dreary Story or A Tedious Story (1889)

edit- Instructing in cures, therapists always recommend that “each case be individualized.” If this advice is followed, one becomes persuaded that those means recommended in textbooks as the best, means perfectly appropriate for the template case, turn out to be completely unsuitable in individual cases.

- When a person hasn’t in him that which is higher and stronger than all external influences, it is enough for him to catch a good cold in order to lose his equilibrium and begin to see an owl in every bird, to hear a dog’s bark in every sound.

- The wealthy are always surrounded by hangers-on; science and art are as well.

- If I were asked to chose between execution and life in prison I would, of course, chose the latter. It’s better to live somehow than not at all.

- Capital punishment kills immediately, whereas lifetime imprisonment does so slowly. Which executioner is more humane? The one who kills you in a few minutes, or the one who wrests your life from you in the course of many years?

- The government is not God. It does not have the right to take away that which it can’t return even if it wants to.

• Any result divided by infinity gives nothing.

The Seagull (1896)

edit- I’m in mourning for my life.

- Act I

- Great Jove angry is no longer Jove.

- Но, я думаю, кто испытал наслаждение творчества, для того уже все другие наслаждения не существуют.

- I should think that for one who has tasted the joys of creation, no other pleasure could exist.

- Anna to Trigorin, Act I

- I should think that for one who has tasted the joys of creation, no other pleasure could exist.

- I try to catch every sentence, every word you and I say, and quickly lock all these sentences and words away in my literary storehouse because they might come in handy.

- Act II

- Do you remember you shot a seagull? A man came by chance, saw it and destroyed it, just to pass the time.

- Act IV

- It’s not a matter of old or new forms; a person writes without thinking about any forms, he writes because it flows freely from his soul.

- Act IV

- Как легко, доктор, быть философом на бумаге и как это трудно на деле!

- Translation: How easy it is, Doctor, to be a philosopher on paper, and how hard it is in life!

- Act IV

Uncle Vanya (1897)

edit- People should be beautiful in every way—in their faces, in the way they dress, in their thoughts and in their innermost selves.

- Act I

- In countries where there is a mild climate, less effort is expended on the struggle with nature and man is kinder and more gentle.

- Act I

- Russian forests crash down under the axe, billions of trees are dying, the habitations of animals and birds are laid waste, rivers grow shallow and dry up, marvelous landscapes are disappearing forever.... Man is endowed with creativity in order to multiply that which has been given him; he has not created, but destroyed. There are fewer and fewer forests, rivers are drying up, wildlife has become extinct, the climate is ruined, and the earth is becoming ever poorer and uglier.

- Act I

- The world perishes not from bandits and fires, but from hatred, hostility, and all these petty squabbles.

- Act I

- Ah, but ignorance is better. At least then there's hope.

- Act II

- A woman can only become a man’s friend in three stages: first, she’s an agreeable acquaintance, then a mistress, and only after that a friend.

- Act II

- Who but a stupid barbarian could burn so much beauty in his stove and destroy that which he cannot make?

- Act I

- We shall find peace. We shall hear the angels, we shall see the sky sparkling with diamonds.

- Act IV

- Those who come a hundred or two hundred years after us will despise us for having lived our lives so stupidly and tastelessly. Perhaps they’ll find a means to be happy.

- Act IV

Gooseberries (1898)

editЧеловек в футляре (сборник)

- At the door of every happy person there should be a man with a hammer whose knock would serve as a constant reminder of the existence of unfortunate people.

- Надо, чтобы за дверью каждого довольного, счастливого человека стоял кто-нибудь с молоточком и постоянно напоминал бы стуком, что есть несчастные...

- It has become customary to say that a man needs only six feet of land. But a corpse needs six feet, not a person.

- Принято говорить, что человеку нужно только три аршина земли. Но ведь три аршина нужны трупу, а не человеку.

- Money, like vodka, turns a person into an eccentric.

- Деньги, как водка, делают человека чудаком.

- He is no longer a city dweller who has even once in his life caught a ruff or seen how, on clear and cool autumn days, flocks of migrating thrushes drift over a village. Until his death he will be drawn to freedom.

- А вы знаете, кто хоть раз в жизни поймал ерша или видел осенью перелётных дроздов, как они в ясные, прохладные дни носятся стаями над деревней, тот уже не городской житель, и его до самой смерти будет потягивать на волю.

The Darling and Other Stories (1899)

editTranslated by Constance Garnett, (full text)

The Darling

- Olenka listened to Kukin with silent gravity, and sometimes tears came into her eyes. In the end his misfortunes touched her; she grew to love him. He was a small thin man, with a yellow face, and curls combed forward on his forehead. He spoke in a thin tenor; as he talked his mouth worked on one side, and there was always an expression of despair on his face; yet he aroused a deep and genuine affection in her.

- She was always fond of some one, and could not exist without loving. In earlier days she had loved her papa, who now sat in a darkened room, breathing with difficulty; she had loved her aunt who used to come every other year from Bryansk; and before that, when she was at school, she had loved her French master. She was a gentle, soft-hearted, compassionate girl, with mild, tender eyes and very good health. At the sight of her full rosy cheeks, her soft white neck with a little dark mole on it, and the kind, naïve smile, which came into her face when she listened to anything pleasant, men thought, "Yes, not half bad," and smiled too, while lady visitors could not refrain from seizing her hand in the middle of a conversation, exclaiming in a gush of delight, "You darling!"

- Kukin's funeral took place on Tuesday in Moscow, Olenka returned home on Wednesday, and as soon as she got indoors, she threw herself on her bed and sobbed so loudly that it could be heard next door, and in the street. "Poor darling!" the neighbours said, as they crossed themselves. "Olga Semyonovna, poor darling! How she does take on!"

- Three months later Olenka was coming home from mass, melancholy and in deep mourning. It happened that one of her neighbours, Vassily Andreitch Pustovalov, returning home from church, walked back beside her. He was the manager at Babakayev's, the timber merchant's. He wore a straw hat, a white waistcoat, and a gold watch-chain, and looked more a country gentleman than a man in trade. "Everything happens as it is ordained, Olga Semyonovna," he said gravely, with a sympathetic note in his voice; "and if any of our dear ones die, it must be because it is the will of God, so we ought have fortitude and bear it submissively." ... All day afterwards she heard his sedately dignified voice, and whenever she shut her eyes she saw his dark beard. She liked him very much. And apparently she had made an impression on him too, for not long afterwards an elderly lady, with whom she was only slightly acquainted, came to drink coffee with her, and as soon as she was seated at table began to talk about Pustovalov, saying that he was an excellent man whom one could thoroughly depend upon, and that any girl would be glad to marry him. Three days later Pustovalov came himself. He did not stay long, only about ten minutes, and he did not say much, but when he left, Olenka loved him--loved him so much that she lay awake all night in a perfect fever, and in the morning she sent for the elderly lady. The match was quickly arranged, and then came the wedding.

- When he reached the street where the school was, he would feel ashamed of being followed by a tall, stout woman, he would turn round and say: "You'd better go home, auntie. I can go the rest of the way alone." She would stand still and look after him fixedly till he had disappeared at the school-gate. Ah, how she loved him! Of her former attachments not one had been so deep; never had her soul surrendered to any feeling so spontaneously, so disinterestedly, and so joyously as now that her maternal instincts were aroused. For this little boy with the dimple in his cheek and the big school cap, she would have given her whole life, she would have given it with joy and tears of tenderness. Why? Who can tell why?

- When she had seen the last of Sasha, she returned home, contented and serene, brimming over with love; her face, which had grown younger during the last six months, smiled and beamed; people meeting her looked at her with pleasure.

- When she put him to bed, she would stay a long time making the Cross over him and murmuring a prayer; then she would go to bed and dream of that far-away misty future when Sasha would finish his studies and become a doctor or an engineer, would have a big house of his own with horses and a carriage, would get married and have children.

Ariadne

- When I was introduced and first had to talk to her, what struck me most of all was her rare and beautiful name--Ariadne. It suited her so wonderfully! She was a brunette, very thin, very slender, supple, elegant, and extremely graceful, with refined and exceedingly noble features. Her eyes were shining, too, but her brother's shone with a cold sweetness, mawkish as sugar-candy, while hers had the glow of youth, proud and beautiful. She conquered me on the first day of our acquaintance

- Ariadne's voice, her walk, her hat, even her footprints on the sandy bank where she used to angle for gudgeon, filled me with delight and a passionate hunger for life.

- My love was pathetic and was soon noticed by every one--my father, the neighbours, and the peasants--and they all sympathised with me. When I stood the workmen ... would bow and say: "May the Kotlovitch young lady be your bride, please God!"

- I remember helping her to get on the bicycle one evening, and she looked so lovely that I felt as though I were burning my hands when I touched her.

- But she was incapable of really loving as I did, for she was cold and already somewhat corrupted. There was a demon in her, whispering to her day and night that she was enchanting, adorable; and, having no definite idea for what object she was created, or for what purpose life had been given her, she never pictured herself in the future except as very wealthy and distinguished ... of a perfect swarm of counts, princes, ambassadors, celebrated painters and artists, all of them adoring her and in ecstasies over her beauty and her dresses. . . .

- Ariadne was herself aware that she was lacking in something. She was vexed and more than once I saw her cry. Another time--can you imagine it?--all of a sudden she embraced me and kissed me. It happened in the evening on the river-bank, and I saw by her eyes that she did not love me, but was embracing me from curiosity, to test herself and to see what came of it. And I felt dreadful. I took her hands and said to her in despair: "These caresses without love cause me suffering!" - "What a queer fellow you are!" she said with annoyance, and walked away.

- After this conversation I lay awake all night and thought of shooting myself. In the morning I wrote five letters and tore them all up.

- I want to believe that in his struggle with nature the genius of man has struggled with physical love too, as with an enemy, and that, if he has not conquered it, he has at least succeeded in tangling it in a net-work of illusions of brotherhood and love; and for me, at any rate, it is no longer a simple instinct of my animal nature as with a dog or a toad, but is real love, and every embrace is spiritualised by a pure impulse of the heart and respect for the woman.

- In reality, a disgust for the animal instinct has been trained for ages in hundreds of generations; it is inherited by me in my blood and forms part of my nature, and if I poetize love, is not that as natural and inevitable in our day as my ears' not being able to move and my not being covered with fur?

- It is true that, in poetizing love, we assume in those we love qualities that are lacking in them, and that is a source of continual mistakes and continual miseries for us. But to my thinking it is better, even so; that is, it is better to suffer than to find complacency on the basis of woman being woman and man being man.

- Seeing me, she uttered a cry of joy, and probably, if we had not been in the park, would have thrown herself on my neck. She pressed my hands warmly and laughed; and I laughed too and almost cried with emotion. Questions followed, of the village, of my father, whether I had seen her brother, and so on. She insisted on my looking her straight in the face, and asked if I remembered the gudgeon, our little quarrels, the picnics. . . .

- She used the formal mode of address in speaking to Lubkov, and when she was going up to bed she said good-night to him exactly as she did to me, and their rooms were on different floors. All this made me hope that it was all nonsense, and that there was no sort of love affair between them, and I felt at ease when I met him. And when one day he asked me for the loan of three hundred roubles, I gave it to him with the greatest pleasure.

- Every day we spent in enjoying ourselves and in nothing but enjoying ourselves; we strolled in the park, we ate, we drank. Every day there were conversations...

- At home in the country I used to feel ashamed to meet the peasants when I was fishing or on a picnic party on a working day; here too I was ashamed at the sight of the footmen, the coachmen, and the workmen who met us. It always seemed to me they were looking at me and thinking: "Why are you doing nothing?"

- At home I found deep snow and twenty degrees of frost. I'm fond of the winter; I'm fond of it because at that time, even in the hardest frosts, it's particularly snug at home. It's pleasant to put on one's fur jacket and felt overboots on a clear frosty day, to do something in the garden or in the yard, or to read in a well warmed room, to sit in my father's study before the open fire, to wash in my country bath-house.

- I became her lover. For a month anyway I was like a madman, conscious of nothing but rapture. To hold in one's arms a young and lovely body, with bliss to feel her warmth every time one waked up from sleep, and to remember that she was there--she, my Ariadne!-- ... I realised, as before, that Ariadne did not love me. But she wanted to be really in love, she was afraid of solitude

- The chief, so to say fundamental, characteristic of the woman was an amazing duplicity. She was continually deceitful every minute, apparently apart from any necessity, as it were by instinct, by an impulse such as makes the sparrow chirrup and the cockroach waggle its antennae. She was deceitful with me, with the footman, with the porter, with the tradesmen in the shops, with her acquaintances; not one conversation, not one meeting, took place without affectation and pretense.

Polinka

- "Do you imagine he'll marry you--is that it? You'd better drop any such fancies. Students are forbidden to marry. And do you suppose he comes to see you with honourable intentions? A likely idea! Why, these fine students don't look on us as human beings . . . they only go to see shopkeepers and dressmakers to laugh at their ignorance and to drink. They're ashamed to drink at home and in good houses, but with simple uneducated people like us they don't care what any one thinks. . . . Well, which feather trimming will you take? And if he hangs about and carries on with you, we know what he is after. . . . When he's a doctor or a lawyer he'll remember you: 'Ah,' he'll say, 'I used to have a pretty fair little thing! I wonder where she is now?' Even now I bet you he boasts among his friends that he's got his eye on a little dressmaker."

- "Pretend to be looking at the things," Nikolay Timofeitch whispers, bending down to Polinka with a forced smile. "Dear me, you do look pale and ill; you are quite changed. He'll throw you over, Pelagea Sergeevna! Or if he does marry you, it won't be for love but from hunger; he'll be tempted by your money. He'll furnish himself a nice home with your dowry, and then be ashamed of you. He'll keep you out of sight of his friends and visitors, because you're uneducated. He'll call you 'my dummy of a wife.' You wouldn't know how to behave in a doctor's or lawyer's circle. To them you're a dressmaker, an ignorant creature."

- "You are the only person who . . . cares about me, and I've no one to talk to but you." . . . "What is there for us to talk about? It's no use talking. . . . You are going for a walk with him to-day, I suppose?" "Yes; I . . . I am." "Then what's the use of talking? Talk won't help. . . . You are in love, aren't you?" "Yes . . ." Polinka whispers hesitatingly, and big tears gush from her eyes "What is there to say?" mutters Nikolay Timofeitch, shrugging his shoulders nervously and turning pale. "There's no need of talk. . . . Wipe your eyes, that's all. . . . I ask for nothing." . . . . For God's sake, wipe your eyes! They're coming this way!" And seeing that her tears are still gushing he goes on louder than ever: "Spanish, Rococo, soutache, Cambray . . . stockings, thread, cotton, silk . . ."

Anyuta

- In the cheapest room of a big block of furnished apartments Stepan Klotchkov, a medical student in his third year, was walking to and fro, zealously conning his anatomy. ... In the window, covered by patterns of frost, sat on a stool the girl who shared his room--Anyuta, a thin little brunette of five-and-twenty, very pale with mild grey eyes. Sitting with bent back she was busy embroidering with red thread the collar of a man's shirt. . . . The clock in the passage struck two drowsily, yet the little room had not been put to rights for the morning....

- "Look here, my good girl . . . sit down and listen. We must part! The fact is, I don't want to live with you any longer." ... She said nothing in answer to the student's words, only her lips began to tremble. "You know we should have to part sooner or later, anyway," . . "You're a nice, good girl, and not a fool . . ." Anyuta put on her coat again, in silence wrapped up her embroidery in paper ... "Why are you crying?" asked Klotchkov. . . . "You are a strange girl, really. . . . Why, you know we shall have to part. We can't stay together for ever." She had gathered together all her belongings, and turned to say good-bye to him, and he felt sorry for her. "Shall I let her stay on here another week?" he thought. "She really may as well stay, and I'll tell her to go in a week;" and vexed at his own weakness, he shouted to her roughly: "Come, why are you standing there? If you are going, go; and if you don't want to, take off your coat and stay! You can stay!"

The Two Volodyas

- The Colonel knew by experience that in women like his wife, Sofya Lvovna, after a little too much wine, turbulent gaiety was followed by hysterical laughter and then tears. He was afraid that when they got home, instead of being able to sleep, he would have to be administering compresses and drops.

- She recalled, how, when she was a child of ten, Colonel Yagitch, now her husband, used to make love to her aunt, and every one in the house said that he had ruined her. And her aunt had, in fact, often come down to dinner with her eyes red from crying, and was always going off somewhere; and people used to say of her that the poor thing could find no peace anywhere. He had been very handsome in those days, and had an extraordinary reputation as a lady-killer. So much so that he was known all over the town, and it was said of him that he paid a round of visits to his adorers every day like a doctor visiting his patients. And even now, in spite of his grey hair, his wrinkles, and his spectacles, his thin face looked handsome, especially in profile.

- They reached home. Getting into her warm, soft bed, and pulling the bed-clothes over her, Sofya Lvovna recalled the dark church, the smell of incense, and the figures by the columns, and she felt frightened at the thought that these figures would be standing there all the while she was asleep. The early service would be very, very long; then there would be "the hours," then the mass, then the service of the day. "But of course there is a God--there certainly is a God; and I shall have to die, so that sooner or later one must think of one's soul, of eternal life

- She thought that before old age and death there would be a long, long life before her, and that day by day she would have to put up with being close to a man she did not love, who had just now come into the bedroom and was getting into bed, and would have to stifle in her heart her hopeless love for the other young, fascinating, and, as she thought, exceptional man. She looked at her husband and tried to say good-night to him, but suddenly burst out crying instead. She was vexed with herself. And all at once he put his arm round her waist, while she, without knowing what she was doing, laid her hands on his shoulders and for a minute gazed with ecstasy, almost intoxication, at his clever, ironical face, his brow, his eyes, his handsome beard.

- "You have known that I love you for ever so long," she confessed to him, and she blushed painfully, and felt that her lips were twitching with shame. "I love you. Why do you torture me?" . . . When half an hour later, having got all that he wanted, he was sitting at lunch in the dining-room, she was kneeling before him, gazing greedily into his face, and he told her that she was like a little dog waiting for a bit of ham to be thrown to it. Then he sat her on his knee, and dancing her up and down like a child, hummed: "Tara-raboom-dee-ay. . . . Tara-raboom-dee-ay." And when he was getting ready to go she asked him in a passionate whisper: "When? To-day? Where?" And held out both hands to his mouth as though she wanted to seize his answer in them. "To-day it will hardly be convenient," he said after a minute's thought. "To-morrow, perhaps."

- And next day she met her lover, and again Sofya Lvovna drove about the town alone in a hired sledge thinking about her aunt.

The Trousseau

- I have seen a great many houses in my time, little and big, new and old, built of stone and of wood, but of one house I have kept a very vivid memory. It was, properly speaking, rather a cottage than a house--a tiny cottage of one story, with three windows

- Soon afterwards the door opened and I saw a tall, thin girl of nineteen, in a long muslin dress with a gilt belt from which, I remember, hung a mother-of-pearl fan. She came in, dropped a curtsy, and flushed crimson. Her long nose, which was slightly pitted with smallpox, turned red first, and then the flush passed up to her eyes and her forehead.

- "My daughter," chanted the little lady, "and, Manetchka, this is a young gentleman who has come," etc. I was introduced, and expressed my surprise at the number of paper patterns. Mother and daughter dropped their eyes. "We had a fair here at Ascension," said the mother; "we always buy materials at the fair, and then it keeps us busy with sewing till the next year's fair comes around again. We never put things out to be made. My husband's pay is not very ample, and we are not able to permit ourselves luxuries. So we have to make up everything ourselves." "But who will ever wear such a number of things? There are only two of you?" "Oh . . . as though we were thinking of wearing them! They are not to be worn; they are for the trousseau!" "Ah, _mamam_, what are you saying?" said the daughter, and she crimsoned again. "Our visitor might suppose it was true. I don't intend to be married. Never!" She said this, but at the very word "married" her eyes glowed.

- I understood, and my heart was heavy.

The Helpmate

- It was past midnight. Nikolay Yevgrafitch knew his wife would not be home very soon, not till five o'clock at least. He did not trust her, and when she was long away he could not sleep, was worried, and at the same time he despised his wife, and her bed, and her looking-glass, and her boxes of sweets, and the hyacinths, and the lilies of the valley which were sent her every day by some one or other, and which diffused the sickly fragrance of a florist's shop all over the house.

- On the table of his wife's room under the box of stationery he found a telegram, and glanced at it casually. It was addressed to his wife, care of his mother-in-law, from Monte Carlo, and signed Michel . . . . The doctor did not understand one word of it, as it was in some foreign language, apparently English. "Who is this Michel? Why Monte Carlo? Why directed care of her mother?"

- Later on he had met the young man himself at his mother-in-law's. And that was at the time when his wife had taken to being very often absent and coming home at four or five o'clock in the morning, and was constantly asking him to get her a passport for abroad, which he kept refusing to do; and a continual feud went on in the house which made him feel ashamed to face the servants.

- He took an English dictionary, and translating the words, and guessing their meaning, by degrees he put together the following sentence: "I drink to the health of my beloved darling, and kiss her little foot a thousand times, and am impatiently expecting her arrival." . . . His pride, his plebeian fastidiousness, was revolted. Clenching his fists and scowling with disgust, he wondered how he, the son of a village priest, brought up in a clerical school, a plain, straightforward man, a surgeon by profession--how could he have let himself be enslaved, have sunk into such shameful bondage to this weak, worthless, mercenary, low creature.

- Of the time when he fell in love and proposed to her, and the seven years that he had been living with her, all that remained in his memory was her long, fragrant hair, a mass of soft lace, and her little feet, which certainly were very small, beautiful feet; and even now it seemed as though he still had from those old embraces the feeling of lace and silk upon his hands and face--and nothing more. Nothing more--that is, not counting hysterics, shrieks, reproaches, threats, and lies--brazen, treacherous lies.

- He remembered how in his father's house in the village a bird would sometimes chance to fly in from the open air into the house and would struggle desperately against the window-panes and upset things; so this woman from a class utterly alien to him had flown into his life and made complete havoc of it.

- It seemed that if a band of brigands had been living in his rooms his life would not have been so hopelessly, so irremediably ruined as by the presence of this woman.

- "You are reckoning on my not knowing English. No, I don't know it; but I have a dictionary. That telegram is from Riss; he drinks to the health of his beloved and sends you a thousand kisses. But let us leave that," the doctor went on hurriedly. "I don't in the least want to reproach you or make a scene. We've had scenes and reproaches enough; it's time to make an end of them.

- This is what I want to say to you: you are free, and can live as you like." There was a silence. She began crying quietly. "I set you free from the necessity of lying and keeping up pretences," Nikolay Yevgrafitch continued. "If you love that young man, love him; if you want to go abroad to him, go.

- She did not believe him and wanted now to understand his secret meaning. She never did believe any one, and however generous were their intentions, she always suspected some petty or ignoble motive or selfish object in them.

- Or he walked about and stopped in the drawing-room before a photograph taken seven years ago, soon after his marriage ... a family group: his father-in-law, his mother-in-law, his wife Olga Dmitrievna when she was twenty, and himself in the rôle of a happy young husband. His father-in-law, a clean-shaven, dropsical privy councillor, crafty and avaricious; his mother-in-law, a stout lady with small predatory features like a weasel, who loved her daughter to distraction and helped her in everything; if her daughter were strangling some one, the mother would not have protested, but would only have screened her with her skirts. Olga Dmitrievna, too, had small predatory-looking features, but more expressive and bolder than her mother's; she was not a weasel, but a beast on a bigger scale!

- Nikolay Yevgrafitch himself in the photograph looked such a guileless soul, such a kindly, good fellow, so open and simple-hearted; his whole face was relaxed in the naïve, good-natured smile of a divinity student, and he had had the simplicity to believe that that company of beasts of prey into which destiny had chanced to thrust him would give him romance and happiness and all he had dreamed of when as a student he used to sing the song "Youth is wasted, life is nought, when the heart is cold and loveless."

Talent

- His landlady, the widow, was out. She had gone off somewhere to hire horses and carts to move next day to town. Profiting by the absence of her severe mamma, her daughter Katya, aged twenty, had for a long time been sitting in the young man's room. Next day the painter was going away, and she had a great deal to say to him. She kept talking, talking, and yet she felt that she had not said a tenth of what she wanted to say. With her eyes full of tears, she gazed at his shaggy head, gazed at it with rapture and sadness.

- When Katya began whimpering, he looked severely at her from his overhanging eyebrows, frowned, and said in a heavy, deep bass: "I cannot marry." "Why not?" Katya asked softly. "Because for a painter, and in fact any man who lives for art, marriage is out of the question. An artist must be free." "But in what way should I hinder you, Yegor Savvitch?" "I am not speaking of myself, I am speaking in general." ". . . Famous authors and painters have never married."

- The artist drank a glass of vodka, and the dark cloud in his soul gradually disappeared, and he felt as though all his inside was smiling within him. He began dreaming. . . . His fancy pictured how he would become great. He could not imagine his future works but he could see distinctly how the papers would talk of him, how the shops would sell his photographs, with what envy his friends would look after him. He tried to picture himself in a magnificent drawing-room surrounded by pretty and adoring women; but the picture was misty, vague, as he had never in his life seen a drawing-room. The pretty and adoring women were not a success either, for, except Katya, he knew no adoring woman, not even one respectable girl. People who know nothing about life usually picture life from books, but Yegor Savvitch knew no books either. He had tried to read Gogol, but had fallen asleep on the second page.

- Before going to bed, Yegor Savvitch took a candle and made his way into the kitchen to get a drink of water. In the dark, narrow passage Katya was sitting, on a box, and, with her hands clasped on her knees, was looking upwards. A blissful smile was straying on her pale, exhausted face, and her eyes were beaming. "Is that you? What are you thinking about?" Yegor Savvitch asked her. "I am thinking of how you'll be famous," she said in a half-whisper. "I keep fancying how you'll become a famous man. . . . I overheard all your talk. . . . I keep dreaming and dreaming. . . ." Katya went off into a happy laugh, cried, and laid her hands reverently on her idol's shoulders.

An Artist's story

- I walked by an old white house of two storeys with a terrace, and there suddenly opened before me a view of a courtyard, a large pond with a bathing-house, a group of green willows, and a village on the further bank, with a high, narrow belfry on which there glittered a cross reflecting the setting sun. For a moment it breathed upon me the fascination of something near and very familiar, as though I had seen that landscape at some time in my childhood.

- The younger sister, Genya, was silent while they were talking of the Zemstvo. She took no part in serious conversation. She was not looked upon as quite grown up by her family, and, like a child, was always called by the nickname of Misuce, because that was what she had called her English governess when she was a child. She was all the time looking at me with curiosity, and when I glanced at the photographs in the album, she explained to me: "That's uncle . . . that's god-father," moving her finger across the photograph. As she did so she touched me with her shoulder like a child, and I had a close view of her delicate, undeveloped chest, her slender shoulders, her plait, and her thin little body tightly drawn in by her sash.

- I felt, as it were, at home in this small snug house where there were no oleographs on the walls and where the servants were spoken to with civility. And everything seemed to me young and pure, thanks to the presence of Lida and Misuce, and there was an atmosphere of refinement over everything.

- She was an energetic, genuine girl, with convictions, and it was interesting to listen to her, though she talked a great deal and in a loud voice--perhaps because she was accustomed to talking at school. On the other hand, Pyotr Petrovitch, who had retained from his student days the habit of turning every conversation into an argument, was tedious, flat, long-winded, and unmistakably anxious to appear clever and advanced.

- When the green garden, still wet with dew, is all sparkling in the sun and looks radiant with happiness, when there is a scent of mignonette and oleander near the house, when the young people have just come back from church and are having breakfast in the garden, all so charmingly dressed and gay, and one knows that all these healthy, well-fed, handsome people are going to do nothing the whole long day, one wishes that all life were like that.

- Byelokurov . . . began a long-winded disquisition on the malady of the age -- pessimism. He talked confidently, in a tone that suggested that I was opposing him. Hundreds of miles of desolate, monotonous, burnt-up steppe cannot induce such deep depression as one man when he sits and talks, and one does not know when he will go.

In the Ravine (1900)

edit- "Grigory Petrovitch, let us weep, let us weep with joy!" he said in a thin voice, and then at once burst out laughing in a loud bass guffaw. "Ho-ho-ho! This is a fine daughter-in-law for you too! Everything is in its place in her; all runs smoothly, no creaking, the mechanism works well, lots of screws in it."

- "Crutch is coming! Crutch! The old horseradish."

- "Yes, that's how it is, child. He who works, he who is patient is the superior."

- "Why did you marry me into this family, mother?" said Lipa.

"One has to be married, daughter. It was not us who ordained it."

- "Why do I love him so much, mamma? Why do I feel so sorry for him?" she went on in a quivering voice, and her eyes glistened with tears. "Who is he? What is he like? As light as a little feather, as a little crumb, but I love him; I love him like a real person. Here he can do nothing, he can't talk, and yet I know what he wants with his little eyes."

- Somewhere far away a bittern cried, a hollow, melancholy sound like a cow shut up in a barn. The cry of that mysterious bird was heard every spring, but no one knew what it was like or where it lived. At the top of the hill by the hospital, in the bushes close to the pond, and in the fields the nightingales were trilling. The cuckoo kept reckoning someone's years and losing count and beginning again. In the pond the frogs called angrily to one another, straining themselves to bursting, and one could even make out the words: "That's what you are! That's what you are!" What a noise there was! It seemed as though all these creatures were singing and shouting so that no one might sleep on that spring night, so that all, even the angry frogs, might appreciate and enjoy every minute: life is given only once.

The Three Sisters (1901)

edit- In two or three hundred years life on earth will be unimaginably beautiful, astounding. Man needs such a life and if it hasn’t yet appeared, he should begin to anticipate it, wait for it, dream about it, prepare for it. To achieve this, he has to see and know more than did his grandfather and father.

- Act I

- What seems to us serious, significant and important will, in future times, be forgotten or won’t seem important at all.

- Act I

- To Moscow, to Moscow, to Moscow!

- Act II

- After us they’ll fly in hot air balloons, coat styles will change, perhaps they’ll discover a sixth sense and cultivate it, but life will remain the same, a hard life full of secrets, but happy. And a thousand years from now man will still be sighing, “Oh! Life is so hard!” and will still, like now, be afraid of death and not want to die.

- Act II

The Cherry Orchard (1904)

edit- Dear and most respected bookcase! I welcome your existence, which has for over one hundred years been devoted to the radiant ideals of goodness and justice.

- Act I

- If there's any illness for which people offer many remedies, you may be sure that particular illness is incurable, I think.

- Act I

- To a heart transformed by love, it is a mandolin.

- Act II

- All Russia is our orchard.

- Act II

- The cherry orchard is now mine!... I bought the estate on which my grandfather and father were slaves, where they were not even permitted in the kitchen.

- Act III

Misattributed

edit- Any idiot can face a crisis; it is this day-to-day living that wears you out.

- Missattributed misquotation of "Just about anybody can face a crisis. It’s that everyday living that’s rough." This occurs in the screenplay of The Country Girl (1954) screenplay by George Seaton, based on a play by Clifford Odets, which was first misattributed to Chekov in 1981, according to Quote Investigator

Quotes about Chekhov

edit- I belong to the first generation of Latin American writers brought up reading other Latin American writers...Many Russian novelists influenced me as well: Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov, Nabokov, Gogol, and Bulgarov.

- Listener indifference, which is reader indifference, is a trademark joke in Chekhov.

- Steven Barthelme, as quoted in "A Belated Apology to Anton Chekhov" by Joe Fassler (19 March 2013)

- I think the first discovery I made for myself which I didn't necessarily share with my family or my friends, but came upon myself, was Russian literature. I've always felt very much enthralled to writers like Dostoevsky, especially, and Chekhov.