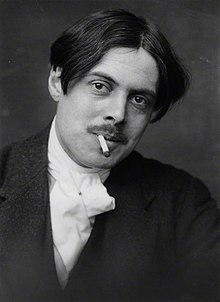

Wyndham Lewis

English painter, writer and critic (1882-1957)

Percy Wyndham Lewis (18 November 1882 – 7 March 1957) was an English polemicist, novelist, essayist, critic and Vorticist painter.

Quotes

edit- 1. Laughter is the Wild Body's song of triumph.

2. Laughter is the climax in the tragedy of seeing, hearing and smelling self-consciously.

3. Laughter is the bark of delight of a gregarious animal at the proximity of its kind.

4. Laughter is an independent, tremendously important, and lurid emotion.

5. Laughter is the representative of Tragedy, when Tragedy is away.

6. Laughter is the emotion of tragic delight.

7. Laughter is the female of Tragedy.

8. Laughter is the strong elastic fish, caught in Styx, springing and flapping about until it dies.

9. Laughter is the sudden handshake of mystic violence and the anarchist.

10. Laughter is the mind sneezing.

11. Laughter is the one obvious commotion that is not complex, or in expression dynamic.

12. Laughter does not progress. It is primitive, hard and unchangeable.- "Inferior Religions" (1917), cited from Lawrence Rainey (ed.) Modernism: An Anthology (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005) pp. 208-9.

- It could perhaps be asserted, even, that the greatest Satire cannot be moralistic at all: if for no other reason, because no mind of the first order has ever itself been taken in, nor consented to take in others, by the crude injunctions of any purely moral code.

- Satire and Fiction (London: The Arthur Press, 1930 [1974]), p. 43.

- The art of advertisement, after the American manner, has introduced into all our life such a lavish use of superlatives, that no standard of value whatever is intact.

- "'Promise' as an Institution", in The Doom of Youth (London: Chatto & Windus, 1932).

- I have been called a Rogue Elephant, a Cannibal Shark, and a crocodile. I am none the worse. I remain a caged, and rather sardonic, lion, in a particularly contemptible and ill-run zoo.

- Blasting and Bombardiering (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1937) p. 12.

- You as a Fascist stand for the small trader against the chain-store; for the peasant against the usurer; for the nation, great or small, against the super-state; for personal business against Big Business; for the craftsman against the Machine; for the creator against the middleman; for all that prospers by individual effort and creative toil, against all that prospers in the abstract air of High Finance or of the theoretic ballyhoo of Internationalism.

- British Union Quarterly, 1937.

- Is it with us a compensatory fact that, being more stupid in the mass, we shoot up higher, when we do shoot up, in dazzling concentrations of intellectual power and so produce what we describe as "genius"? For "genius" is with us an individual thing. Whereas all Jews are little geniuses.

- The Jews: Are They Human? (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1939), p. 68.

- The prime essential in the solution of the "Jewish problem" is to eradicate entirely from our minds all prejudice and superstition about the Jew.

- The Jews: Are They Human? (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1939), p. 107.

- The earth has become one big village, with telephones laid on from one end to the other, and air transport, both speedy and safe.

- America and Cosmic Man (New York: Doubleday, [1948] 1949) p. 21.

- Great Britain is certainly suspect to Americans. They cannot make head or tail of her. She is a stuck-up old girl who owes a lot of money - an odd thing for such a highly respectable old lady to do. She is rather flighty, which is alarming in one so old - she never seems quite serious, that is - goes into giggles all of a sudden, or smiles enigmatically, if politely. She seems to the average American slightly phoney. Let us face up to that. She has many habits which baffle and put one on one's guard - the curious way she has of speaking English with a foreign accent, for instance. Then she must be the most quarrelsome old dame which ever stepped: always - umbrella in hand - getting into scraps with her neighbours, and spitting at them over the garden wall.

- The Hitler Cult (Dent, 1949)

- Wherever there is objective truth there is satire.

- Rude Assignment: An Intellectual Autobiography (1950). Santa Barbara: Black Sparrow Press, 1984, p. 52.

- Certainly Mr Eliot in the twenties was responsible for a great vogue for verse-satire. An ideal formula of ironic, gently "satiric", self-expression was provided by that master for the undergraduate underworld, tired and thirsty for poetic fame in a small way. The results of Mr Eliot are not Mr Eliot himself: but satire with him has been the painted smile of the clown. Habits of expression ensuing from mannerism are, as a fact, remote from the central function of satire. In its essence the purpose of satire — whether verse or prose — is aggression. (When whimsical, sentimental, or "poetic" it is a sort of bastard humour.) Satire has a great big glaring target. If successful, it blasts a great big hole in the center. Directness there must be and singleness of aim: it is all aim, all trajectory.

- As quoted in Kenneth Allott ed., Contemporary Verse (Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books, 1954), p. 61.

The Art of Being Ruled (1926)

edit- The puritanic potentialities of science have never been forecast. If it evolves a body of organized rites, and is established as a religion, hierarchically organized, things more than anything else will be done in the name of "decency". The coarse fumes of tobacco and liquors, the consequent tainting of the breath and staining of white fingers and teeth, which is so offensive to many women, will be the first things attended to.

- "The Family and Feminism".

- The ideas of a time are like the clothes of a season: they are as arbitrary, as much imposed by some superior will which is seldom explicit. They are utilitarian and political, the instruments of smooth-running government.

- "Beyond Action and Reaction".

- Men were only made into "men" with great difficulty even in primitive society: the male is not naturally "a man" any more than the woman. He has to be propped up into that position with some ingenuity, and is always likely to collapse.

- "Call Yourself a Man!"

- The Relativity theory, the copernican upheaval, or any great scientific convulsion, leaves a new landscape. There is a period of stunned dreariness; then people begin, antlike, the building of a new human world. They soon forget the last disturbance. But from these shocks they derive a slightly augmented vocabulary, a new blind spot in their vision, a few new blepharospasms or tics, and perhaps a revised method of computing time. (p. 336)

- "The Great God Flux".

- I am an artist, and, through my eye, must confess to a tremendous bias. In my purely literary voyages my eye is always my compass. “The architectural simplicity” – whether of a platonic idea or greek temple – I far prefer to no idea at all, or no temple at all, or, for instance, to most of the complicated and too tropical structures of India. Nothing could ever convince my EYE – even if my intelligence were otherwise overcome – that anything that did not possess this simplicity, conceptual quality, hard exact outline, grand architectural proportion, was the greatest art. Bergson is indeed the arch enemy of every impulse having its seat in the apparatus of vision, and requiring a concrete world. Bergson is the enemy of the Eye, from the start; though he might arrive at some emotional compromise with the Ear. But I can hardly imagine any way in which he is not against every form of intelligent life. (p. 338)

- "The Great God Flux".

The Apes of God (1930)

edit- The Apes of God (Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Modern Classics, 1965)

- The modern man whether of Bloomsbury Baltimore or Berlin has vanquished vanity — he offers himself to his own inspection as the worm he turns out to be. If he is vain at all, and it must be conceded that self-love is hard to kill, it is about his humility. His own Vernichtung is his greatest pride the laying bare of the nullity, the Nichtigkeit, that is the 'self' at the heart of energy (which is merely the doctrine of Xt that 'he who humbleth himself shall be exalted' ! Be modest, protest you are nobody, a biological bagatelle and hi presto! you will get top-marks, and be given authority, that is the idea — it is the christian strategy. …)

- Dr Frumpfsusan of Zurich in Part 2: "The Virgin", p. 89.

- The self-feeling bears no relation, amongst quite normal men and women, to physical fact. The nature of their particular physique, is not that the last thing of which they think? Look, an intensely ill-favoured woman she will frequently behave as if she were very attractive. No one is surprised — for they in their turn are they not beauties too? stunted puny men, to turn to men, do they not possess the assurance of a champion athlete? Well then, all these people have the assurance of being what they are not: whatever happens, a something more favourable than the facts isn't it! This is the rule of the normal average.

- Dr Frumpfsusan in Part 2: "The Virgin", p. 92.

- The novelty of any time enables people to pretend that they are existing in the state of society that in fact they have superseded. (It is an old political expedient to pretend to be what you have destroyed.) They will pretend that their abuses are old abuses and that only their reforms are new.

- From Pierpoint's 'encyclical' in Part 3: "The Encyclical", p. 126.

- Being born in a stable does not make you a horse. But living in a studio produces in some persons a feeling that they should dabble and daub a little.

- From Pierpoint's 'encyclical' in Part 3: "The Encyclical", p. 129.

- The second cause (and this applies to a much smaller number of such people — only indeed, to the very cream and élite of them) is that some (born with a happy or unhappy knack not possessed by their less talented fellows) produce a little art themselves — more than the inconsequent daubing and dabbing we have noticed, but less than the 'real thing'. And with this class you come to the Ape of God proper. For with these unwanted and unnecessary labours, and the amour-propre associated with their results, envy steps in. The complication of their malevolence that ensues is curious to watch. But it redoubles, in the natural course of things, the fervour of their caprice or ill-will to the 'professional' activities of the effective artist — that rare man born for an exacting intellectual task, and devoting his life unsparingly to it.

- From Pierpoint's 'encyclical' in Part 3: "The Encyclical", p. 130.

- By adopting the life of the artist the rich have not learnt more about art, and they respect it less. With their more irresponsible 'bohemian' life they have left behind their 'responsibilities' — a little culture among the rest. Indeed they are almost as crudely ignorant as is the traditional painter. Besides — living in cafés, studios and 'artistic' flats — they are all 'artists' in a sense themselves. They have made the great discovery that every one wielding a brush or pen is not a 'genius', any more than they are. But they have absorbed a good deal of the envy of those who are not 'geniuses' for those who are (having in a sense placed themselves upon the same level) — and the contempt of those who are, for those who are not. The result is that they abominate good art as much as bad artists do, and have as much contempt for bad art as have good artists! There is more indifference to and often hatred of every form of art in these pseudo-artistic circles — in the studios, in short, now mostly occupied by them — than in all the rest of the world put together.

- From Pierpoint's 'encyclical' in Part 3: "The Encyclical", pp. 132–133.

- I am not in agreement with the current belief in a strained 'impersonality' as the secret of artistic success. Nor can I see the sense of pretending — as it must be a pretence, and a thin one, too — that in my account to you of what I have seen I can be impartial and omniscient. That would be in the nature of a bluff or a blasphemy. There can only be one judge and I am not he.

I am not a judge but a party. All I can claim is that my cause is not an idle one — that I appeal less to passion than to reason.

- From Pierpoint's 'encyclical' in Part 3: "The Encyclical", p. 133.

- I should invent very little if I were a flatterer. […] I should just encourage people to describe themselves, and use the description they seemed most to relish.

- Horace Zagreus in Part 9: "Chez Lionel Kein Esq.", p. 258.

- Society is a defensive organization against the incalculable. It is so constituted as to exclude and to banish anything, or any person, likely to disturb its repose, to rout its pretensions, wound its vanity, or to demand energy or a new effort, which it is determined not to make.

- Horace Zagreus in Part 9: "Chez Lionel Kein Esq.", p. 274.

- [T]he world created by Art — Fiction, Drama, Poetry etc. — must be sufficiently removed from the real world so that no character from the one could under any circumstances enter the other (the situation imagined by Pirandello), without the anomaly being apparent at once.

- Horace Zagreus in Part 9: "Chez Lionel Kein Esq.", p. 279.

- Yet it is true that in our democratic society flattery does take the form of saying to people that they are like other people — rather than unlike or possessing something peculiarly their own. And the personal advantages that are chosen to flatter them about are those that they share with great crowds of other people.

- Horace Zagreus in Part 9: "Chez Lionel Kein Esq.", p. 297.

- [I]f within a decade and a half you massacre ten million people in war and another ten million in civil war, it is not easy after that to return to a morality that regards it as wrong to pocket a salt-spoon.

- Horace Zagreus in Part 12: "Lord Osmund's Lenten Party", § II: "The Players Solus", p. 429.

- We have the immense background of War and of Revolution. That is enough — the blood is gratis! Both the soldier and the communist enrol themselves to murder — one under militarist rules, the other under marxist disciplines. But both are homicide-clubs, you call your victim "Hun", you call him "Bourgeois", it is all one — no, wars and communes have cheapened murder.

- Horace Zagreus in Part 12: "Lord Osmund's Lenten Party", § II: "The Players Solus", p. 430.

- Morality is of the surface. But also the values that decide whether a person is ridiculous or free from absurdity are pure conventions of a society, they exist only in a surface-world, of two dimensions.

- Horace Zagreus in Part 12: "Lord Osmund's Lenten Party", § V: "At the American Bar", p. 471.

- Satire to be good must be unfair and single-minded. To be backed by intense anger is good — though absolutely not necessary.

- Horace Zagreus in Part 12: "Lord Osmund's Lenten Party", § V: "At the American Bar", p. 472.

- That is the sacrosanct period-of-periods — the Victorian death, the birth of Decadence! Ah the pioneer naughtiness of the "Naughty Nineties", that 'Made the World Safe for Homosexuality!'

- Bertram Starr-Smith (Blackshirt) in Part 12: "Lord Osmund's Lenten Party", § IX: "Blackshirt Explains Ratner. Ratner Blackshirt", p. 528.

- Every pastime has its attendant politics.

- Bertram Starr-Smith (Blackshirt) in Part 12: "Lord Osmund's Lenten Party", § X: "The Old Colonels", p. 553.

- Sex was really all bluff — power the thing.

- Julius Ratner, thinking "Adler-like (being a minor Adler)", in Part 12: "Lord Osmund's Lenten Party", § XII: "Now Jonathan Bell Was an Old John Bull", p. 565.

- [D]oes not all power that is real exact that it shall be visible!

- Another Adlerian thought of Julius Ratner in Part 12: "Lord Osmund's Lenten Party", § XX: "God Always Desires to Manifest Himself", p. 611.

- The als ob doctrine of a sportsmanlike average, that is the perfect democrat. […] If you do not acquire this simple democratic habit of make-believe, there is no place for you in contemporary life.

- Horace Zagreus in Part 13: "The General Strike", p, 634.

Quotes about Wyndham Lewis

edit- There's Wyndham Lewis fuming out of sight,

That lonely old volcano of the Right.- W. H. Auden "Letter to Lord Byron", in W. H. Auden and Louis MacNeice Letters from Iceland (London: Faber, 1937).

- A buffalo in wolf's clothing.

- Robbie Ross, quoted in Wyndham Lewis Blasting and Bombardiering (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1937) p. 12.

- I do not think I had ever seen a nastier-looking man.... Under the black hat, when I had first seen them, the eyes had been those of an unsuccessful rapist.

- Ernest Hemingway, in his biography, A Moveable Feast, chapter 12. (Scribners, 1964).

- Lewis sought no disciples, nor does he offer a program or solution, rather his contribution is a critical discipline. Lewis is a stimulant, a mode of perception, rather than a position or practice.

- Marshall McLuhan, "A Critical Discipline," Renascence 12, no. 2 (Winter, 1960): 94-95.