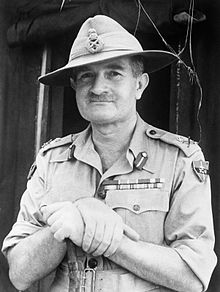

William Slim, 1st Viscount Slim

former Governor-General of Australia (1891-1970)

Field Marshal William Joseph Slim, KG, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE, DSO, MC, KStJ (6 August 1891 – 14 December 1970), usually known as Bill Slim, was a British military commander and the 13th Governor-General of Australia. In the early 1930s, Slim also wrote novels, short stories, and other publications under the pen name Anthony Mills.

Quotes

editDefeat Into Victory (1961)

edit- Condensed version of the multi-volume book originally published in 1956

- Patterson-Knight, my "Q" staff officer, who had been at Shwegyin for some days supervising embarkation and was a conspicuous figure in his exquisitely cut, but by now somewhat soiled, jodhpurs, took a tommy gun and went into the fray. About an hour later he came back and exchanged the tommy-gun for a rifle, explaining that "The little yellow baskets are a bit farther off now!"

- p. 82

- He would have been a brave American who would have stood up to Joe Stilwell to his face.

- p. 179

- Generals who are terribly busy all day and half the night, who fuss round, posting platoons, and writing march tables, wear out not only their subordinates but themselves. Nor have they, when the real emergency comes, the reserve of vigor that will enable them, for days if necessary, to do with little rest or sleep.

- p. 184

- ...any Japanese officer wishing to commit suicide would be given every facility.

- p. 442

- For them I had none of the sympathy of soldier for soldier that I had felt for Germans, Turks, Italians, or Frenchmen that by the fortune of war I had seen surrender. I knew too well what these men and those under their orders had done to their prisoners. They sat there apart from the rest of humanity. If I had no feeling for them, they, it seemed, had no feeling of any sort, until Itagaki, who had replaced Field-Marshal Terauchi, laid low by a stroke, leaned forward to affix his seal to the surrender document. As he pressed heavily on the paper, a spasm of rage and despair twisted his face. Then it was gone, and his mask was as expressionless as the rest. Outside, the same Union Jack that had been hauled down in surrender in 1942 flew again at the masthead. The war was over.

- p. 442

- The strength of the Japanese Army lay, not in its higher leadership which once its career of success had been checked became confused, nor in its special aptitude for jungle warfare, but in the spirit of the individual Japanese soldier. He fought and marched till he died. If five hundred Japanese were ordered to hold a position, we had to kill four hundred and ninety-five before it was ours- and then the last five had killed themselves. It was this combination of obedience and ferocity that made the Japanese Army, whatever its condition, so formidable, and which would make any army formidable. It would make a European army invincible.

- p. 447

- The more modern war becomes, the more essential appear the basic qualities that from the beginning of history have distinguished armies from the mobs. The first of these is discipline.

- p. 451

- Armies do not win wars by means of a few bodies of super-soldiers but by the average quality of their standard units. Anything, whatever short cuts to victory it may promise, which thus weakens the army spirit, is dangerous. Commanders who have used these special forces have found, as we did in Burma, that they have another grave disadvantage- they can be employed actively for only restricted periods. Then they demand to be taken out of the battle to recuperate, while normal formations are expected to have no such limitations to their employment. In Burma, the time spent in action with the enemy by special forces was only a fraction of that endured by the normal divisions, and it must be remembered that risk is danger multiplied by time.

- p. 456

- Private armies, and for that matter private air forces- are expensive, wasteful, and unnecessary.

- p. 457

- In these pages I have written much of generals and of staff officers; of their problems, difficulties, and expedients, their successes and their failures. Yet there is one thought that I should like to be the over-all and final impression of this book- that the war in Burma was a soldier's war. There comes a moment in every battle against a stubborn enemy when the result hangs in the balance. Then the general, however skillful and farsighted he may have been, must hand over to his soldiers, to the men in the ranks and to their regimental officers and leave them to complete what he has begun. The issue then rests with them, on their courage, their hardihood, their refusal to be beaten either by the cruel hazards of nature or by the fierce strength of their human enemy. That moment came early and often in the fighting in Burma; sometimes it came when tired, sick men felt alone, when it would have been so easy for them to give up, when only will, discipline and faith could steel them to carry on. To the soldiers of the many races who, in the comradeship of the Fourteenth Army, did go on, and to the airmen who flew with them and fought over them, belongs the true glory of achievement. It was they who turned Defeat into Victory.

- p. 460