William Burges

English architect

William Burges (2 December 1827 – 20 April 1881) was an English architect and designer.

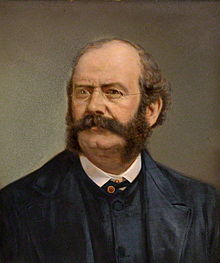

- William Burges, 1865

Quotes

edit- Use a good strong thick bold line so that we may get into the habit of leaving out those prettinesses which only cost money and spoil our design.

- Attributed to William Burges (1860) paper on architectural drawing in: Sir Reginald Theodore Blomfield (1912) Architectural drawing and draughtsmen, Cassell & company, limited, 1912. p. 6-7

- The civil engineer is the real 19th century architect.

- William Burges in: The Ecclesiologist, Vol. 28, 1867, p. 156: Cited in Crook (2004)

- If we copy, the thing never looks right [and] the same occurs with regard to those buildings which do not profess to be copies; both they and the copies want spirit. They are dead bodies... We are at our wits.

- William Burges "Art and Religion", in: The Church and the World: Essays on Questions of the Day, Orby Shipley ed., London, 1868, pp. 574-98; As cited in: John Pemble. Venice rediscovered. Clarendon Press, 16 mrt. 1995. p. 133

- What I set myself to do was this, to write a sort of grammar of thirteenth-century architecture, and to illustrate it with carefully measured details. I moreover resolved, when I did measure details or buildings, to do the part I wanted, and not to waste time by trying to make a finished drawing by means of the surroundings. The plan of the book fell through, for I had scarcely been at work two months before the advertisement of M. Viollet-le-Duc's Dictionary appeared, and I then continued tho drawings for my own instruction and without any intention of publication.

- William Burges, Architectural Drawings, London, 1870. p. 1; As cited in American Architect and Building News. 1881. Vol. 9. p. 236

- I have been brought up in the 13th century belief, and in that belief I intend to die.

- William Burges The Builder, Vol 34, 1876, p. 18: Cited in: Peter Galloway, The cathedrals of Ireland, 1992, p. 62; Also cited in Crook (2004)

Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865

editWilliam Burges Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865

- It has been well observed that the world, more especially the English portion of it, during the last half century, has been in its working dress; that is to say, although we have done some very wonderful things in the way of mechanics, and have produced other things which are marvels of cheapness, yet as regards the production of really beautiful objects, particularly those required in every-day life, we have been behind most other epochs of civilization.

- p. 1 : Preface

- Of course there is no prima facie reason why cheap things should be ugly, for a die or mould of a good design costs no more than a bad one; but still the fact remains that the objects in use in every-day life are not beautiful, and it is to effect a change in this respect that the Government have established Schools of Design and the excellent Museum of which I shall have to speak hereafter.

- p. 1 : Preface

- Great praise must also be given to the Society of Arts for beginning the movement and carrying it on to the present time; and although the sphere of its action must necessarily be infinitely smaller than that of the Government Schools, yet we should always remember that the initiative of our great English exhibitions of industry came from the Society, and that it is to those exhibitions that we owe the stirring among the dry bones of industrial art which is now taking place.

- p. 1 : Preface

- Decidedly the best application of art to industry is when a great many copies are made from an exceedingly good pattern.

- p. 1

- The real mission of machinery is to reduce pounds to shillings and shillings to pence.

- p. 2

- Pugin says in one of his works that had he a cathedral to build, one of the first things he would do would be to set up a lathe to turn the smaller columns.

- p. 2

- Since the great French Revolution all colour has been gradually dying out of the male costume, until we have got reduced to our present gamut of brown, black and neutral tint; which, combined with the chimney-pot hat and the swallow-tailed coat, form a costume by no means particularly adapted to refresh the eye seeking for form or colour.

- p. 8

- Allowing, therefore, the great usefulness of the Government Schools, the Exhibitions, and the Museums both public and private, the question now arises as to what are the impediments to our future progress. The principal ones appear to me to be three.

- A want of a distinctive architecture, which is fatal to art generally.

- The want of a good costume, which is fatal to colour; and

- The want of a sufficient teaching of the figure, which is fatal to art in detail.

- It will perhaps be as well to take these one by one.

- The most fatal impediment of the three is undeniably the want of a distinctive architecture in the nineteenth century. Architecture is commonly called the mother of all the other arts, and these latter are all more or less affected by it in their details. In almost every age of the world except our own only one style of architecture has been in use, and consequently only one set of details. The designer had accordingly to master, 1. the figure, and the great principles of ornament; 2. those details of the architecture then practised which were necessary to his trade; and 3. the technical processes. Now what is the case in the present day? If we take a walk in the streets of London we may see at least half-a-dozen sorts of architecture, all with different details; and if we go to a museum we shall find specimens of the furniture, jewellery, &c., of these said different styles all beautifully classed and labelled. The student, instead of confining himself to one style as in former times, is expected to be master of all these said half-dozen, which is just as reasonable as asking him to write half-a-dozen poems in half-a-dozen languages, carefully preserving the idiomatic peculiarities of each. This we all know to be an impossibility, and the end is that our student, instead of thoroughly applying the principles of ornament to one style, is so bewildered by having the half-dozen on his hands, that he ends by knowing none of them as he ought to do. This is the case in almost every trade; and until the question of style gets gets settled, it is utterly hopeless to think about any great improvement in modern art.

- p. 8-9; Partly cited in: Journal of the Royal Society of Arts. Vol. 99. 1951. p. 520

- At present the fashion appears to have set in in favour of two very distinct styles. One is a very impure and bastard Italian, which is used in most large secular buildings; and the other is a variety of the architecture of the thirteenth century, often, I am sorry to say, not much purer than its rival, especially in the domestic examples, although its use is principally confined to ecclesiastical edifices. It is needless to say that the details of these two styles are as different from each other as light from darkness, but still we are expected to master both of them. But it is most sincerely to be hoped that in course of time one or both of them will disappear, and that we may get something of our own of which we need not be ashamed. This may, perhaps, take place in the twentieth century, it certainly, as far as I can see, will not occur in the nineteenth.

- p. 9; Partly cited in: The New Encyclopaedia Britannica: Macropaedia (19 v.) Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1983. p. 514

- There are two great uses of antiquarian studies. One of them is to enable us to conjure up as if by the magician's wand the dress, furniture, architecture, &c., of past ages, so that we can live, as it were, in many centuries almost at the same moment. This is a very great and a very pleasant species of knowledge, but it is not particularly useful in this work-a-day world; and it sometimes, like other knowledge, renders its possessor far from happy, more especially when he goes to the theatre, and sees all sorts of anachronisms and impossibilities a. The other use of antiquarian studies is to restore disused arts, and to get all the good we can out of them for our own improvement.

- p. 13

- We now come to a third evil, namely, our very unsatisfactory, not to say ugly, furniture. It may be objected that it does not much matter what may be the exact curve of the legs of the chair a man sits upon, or of the table off which he eats his dinner, provided the said articles of furniture answer their respective uses ; but, unfortunately, what we see continually before our eyes is likely, indeed is quite sure, to exercise a very great influence upon our taste, and therefore the question of beautiful versus ugly furniture does become a matter of very great importance. I might easily enlarge upon the enormities, inconveniences, and extravagances of our modern upholsterers, but that has been so fully done in a recent number of the "Cornhill Magazine" that I may well dispense with the task.

- p. 69: Partly cited in: Dinah Eastop, Kathryn Gill (2012) Upholstery Conservation: Principles and Practice. p. 47.

- Eastop & Gil commented that:

Burges held strong views about furniture, and protested at the "enormities, inconveniences, and upholsterers." (1865: 69) He advocated the use of the medieval style, because "not only did its duty as furniture, but spoke and told a story" (1865: 71).

- The great feature of our medieval chamber is the furniture ; this, in a rich apartment, would be covered with paintings, both ornaments and subjects; it not only did its duty as furniture, but spoke and told a story.

- p. 71; Partly cited in: Export of objects of cultural interest 2010/11: 1 May 2010 - 30 April 2011. Stationery Office, 13 dec. 2011

- Nothing is more perishable than worn-out apparel, yet, thanks to documentary evidence, to the custom of burying people of high rank in their robes, and to the practice of wrapping up relics of saints in pieces of precious stuffs, we are enabled to form a veiy good idea of what these stuffs were like and where they came from. In the first instance they appear to have come from Byzantium, and from the East generally; but the manufacture afterwards extended to Sicily, and received great impetus at the Norman conquest of that island; Roger I. even transplanting Greek workmen from the towns sacked by his army, and settling them in Sicily. Of course many of the workers would be Mohammedans, and the old patterns, perhaps with the addition of sundry animals, would still continue in use; hence the frequency of Arabic inscriptions in the borders, the Cufic character being one of the most ornamental ever used. In the Hotel de Clu^ny at Paris are preserved the remains of the vestments of a bishop of Bayonne, found when his sepulchre was opened in 1853, the date of the entombment being the twelfth century. Some of these remains are cloth of gold, but the most remarkable is a very deep border ornamented with blue Cufic letters on a gold ground; the letters are fimbriated with white, and from them issue delicate red scrolls, which end in Arabic sort of flowers: this tissue probably is pure Eastern work. On the contrary, the coronation robes of the German emperors, although of an Eastern pattern, bear inscriptions which tell us very clearly where they were manufactured: thus the Cufic characters on the cope inform us that it was made in the city of Palermo in the year 1133, while the tunic has the date of 1181, but then the inscription is in the Latin language. The practice of putting Cufic inscriptions on precious stuffs was not confined to the Eastern and Sicilian manufactures; in process of time other Italian cities took up the art, and, either because it was the fashion, or because they wished to pass off" their own work as Sicilian or Eastern manufacture, imitations of Arabic characters are continually met with, both on the few examples that have come down to us of the stuffs themselves, or on painted statues or sculptured effigies. These are the inscriptions which used to be the despair of antiquaries, who vainly searched out their meaning until it was discovered that they had no meaning at all, and that they were mere ornaments. Sometimes the inscriptions appear to be imitations of the Greek, and sometimes even of the Hebrew. The celebrated ciborium of Limoges work in the Louvre, known as the work of Magister G. Alpais, bears an ornament around its rim which a French antiquary has discovered to be nothing more than the upper part of a Cufic word repeated and made into a decoration.

- p. 85; Cited in: "Belles Lettres" in: The Westminster Review, Vol. 84-85. Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1865. p. 143

- Quote was introduced with the phrase:

In the lecture on the weaver's art, we are reminded of the superiority of Indian muslins and Chinese and Persian carpets, and the gorgeous costumes of the middle ages are contrasted with our own dark ungraceful garments. The Cufic inscriptions that have so perplexed antiquaries, were introduced with the rich Eastern stuffs so much sought after by the wealthy class, and though, as Mr. Burges observes

- We have no architecture to work from at all; indeed, we have not even settled the point de depart... our art... is domestic, and... the best way of advancing its progress is to do our best in our own houses... if we once manage to obtain a large amount of art and colour in our sitting-rooms... the improvement may gradually extend to our costume, and perhaps eventually to the architecture of our houses.

- p. 91-92; Cited in: "William Burges 1827-1881 London Architect" in: In Pursuit of Beauty: Americans and the Aesthetic Movement. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1 jan. 1986. p. 405

Quotes about William Burges

edit- The thirteenth century, in particular, was Burges’s chosen field, and he modelled his style of draughtsmanship on the famous sketchbook of Villard de Honnecourt in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

- J. Mordaunt Crook, "Burges, William (1827–1881)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- He was almost the first artist I ever knew... He used to give the quaintest little tea-parties in his bare bachelor chambers, all very dowdy, but the meal served in beaten gold, the cream poured out of a single onyx, and the tea structured in its descent on account of real rubies inside the pot. He was much blinder than any near-sighted man I ever knew, and once, when with me in the country, mistook a peacock seen en face for a man. His work was really more jewel-work than architecture, just because he was so blind, but he had real genius, I am sure.

- Edmund Gosse to Henry Austin Dobson (23 April 1881), quoted in Evan Charteris, The Life and Letters of Sir Edmund Gosse (1931), p. 147

- There is a babyish party named Burges

- Who from infancy hardly emerges;

- If you had not been told

- He’s disgracefully old,

- You’d offer a bull’s-eye to Burges.

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti (1911) The Collected Works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, p. 274