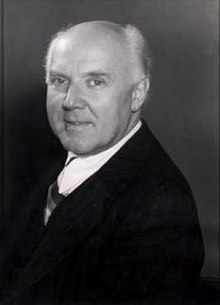

Walter Gieseking

Walter Wilhelm Gieseking (5 November 1895 – 26 October 1956) was a French-born German pianist and composer.

Quotes about Gieseking

edit- A tall, hulking man walked on to the stage at Carnegie Hall last week, bent himself into an awkward bow at the piano, and played superbly Bach’s Partita No. 2 in C Minor, three Scarlatti sonatas, Schumann’s C Major Fantasia and the first book of Debussy preludes. He was Walter Gieseking, come from Germany for another extended tour, and he played, as he has always played, music that he himself has tried truly and found good.

- Time Magazine, February 24, 1929

- Three seasons have passed since Gieseking made an inconspicuous dé in Æolian Hall, Manhattan (TIME, Feb. 22, 1926). “His European notices were so superlative,” said Manager Charles L. Wagner afterward, “I knew no one would believe them so I decided to let his music speak for itself.”

- Time Magazine, February 24, 1929

- His music spoke so eloquently that Sunday afternoon that members of the small audience told their friends. No one, according to some, had ever played Bach like Gieseking, and they rhapsodized over an amazing technic, a style that was as fluent and easy as it was immaculate. But his Bach, others said, could not compare with his Debussy which surely was the essence of poetry. The controversy, as over most artistic matters, might have been endless, for Gieseking is not a specialist.

- Time Magazine, February 24, 1929

- He is, critics say unanimously, a great musician. To appraise him seems almost impertinent and so they write of his playing in awkward, halting sentences which struggle with big words like “pellucid” and “perfection.”

- Time Magazine, February 24, 1929

- Unforgettable were Kreisleriana, Davidsbündlertänze, the Bach Variations by Reger. Those three—unforgettable. You know, he wasn't a man to study much. He left everything to the intuition. Sometimes it worked and sometimes not. But his sound was out of place in Beethoven, I thought. And I didn't appreciate him very much as an interpreter of Debussy—which might sound strange, because he was so well known as a Debussy interpreter. The immaterial pianissimos were fantastic. But he stayed on the level of sound. I admired Erdmann much more as a musician.

- Claudio Arrau, quoted in Joseph Horowitz, Arrau on Music and Performance (1982)

- I was impressed mostly by Gieseking [Horowitz said in 1987]. He had a finished style, played with elegance, and had a fine musical mind.

- Vladimir Horowitz, quoted in Harold C. Schonberg, Horowitz: his life and music

is an enchanted thing like the glaze on a

katydid-wing subdivided by sun till the nettings are legion.

Like Gieseking playing Scarlatti;like the apteryx-awl as a beak, or the

kiwi's rain-shawl of haired feathers, the mind feeling its way as though blind,

walks with its eyes on the ground.It has memory's ear that can hear without

having to hear. Like the gyroscope's fall, truly unequivocal

because trued by regnant certainty,it is a power of strong enchantment. It

is like the dove- neck animated by sun; it is memory's eye;

it's conscientious inconsistency.It tears off the veil; tears the temptation, the

mist the heart wears, from its eyes -- if the heart has a face; it takes apart

dejection. It's fire in the dove-neck'siridescence; in the inconsistencies

of Scarlatti. Unconfusion submits its confusion to proof; it's

not a Herod's oath that cannot change.- Marianne Moore, "The mind is an enchanting thing"

- Gieseking played all of the German composers and went as far afield as the Rachmaninoff concertos. He was one of the few international favorites who interested himself in contemporary music, [...] But his greatest fame came as an interpreter of Debussy and Ravel. In his prime (about 1920 to 1939; after the war he sounded almost like a different pianist) there was no subtler colorist. His knowledge of pedal technique was supreme, and in particular he was a master of half-pedal effects. Never did he create an ugly sound. The sheer limpidity and transparency of his playing would alone have been memorable even if it had not been backed up by a fine musical mind.

- Harold Schonberg, The Great Pianists (revised ed., 1987), p. 448

Walter Gieseking was a victim -- artistically, at least -- of World War II. When the Germans started the war, Gieseking (1895-1956) was among the greatest pianists alive. When Germany was defeated six years later, Gieseking, though only 50 years old, was a shadow of his former self. Although he was later cleared by an Allied court, Gieseking -- whose world fame would have made him welcome anywhere -- willingly collaborated in the cultural endeavors of the Third Reich.

What remained of him pianistically, however, made it seem as if he had been punished by a higher court. Although his reputation as a great pianist remained until his death in 1956, Gieseking's numerous postwar recordings -- many of which continue to be available on the EMI label -- have always called that reputation in doubt. Even though some of those recordings, particularly those of the music of Debussy and Ravel, are distinguished enough, none justifies Gieseking's huge reputation.

One is grateful, therefore, that this year's Gieseking centennial has brought forth several of the pianist's prewar recordings, most recently the first two volumes (a third is expected in the next few months) of the pianist's concerto legacy (APR) and another disc that collects four of the Beethoven piano sonatas Gieseking recorded between 1931-39.

These performances show us a pianist who was not merely a great virtuoso, but the man who liberated the pedal. Like the two pianists most influenced by his example -- Sviatoslav Richter and Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli -- Gieseking's imaginative use of the pedal, combined with his sophisticated ear, permitted him to cultivate a tonal palette without antecedent in its range and subtlety of color and dynamics. And while Gieseking may not have been a profoundly emotional interpreter, he had a profoundly musical mind that rarely failed to bring music to life.

- Stephen Wigler, "Lightness made Gieseking reigning pre-WWII pianist", The Baltimore Sun (August 27, 1995)