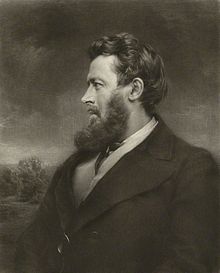

Walter Bagehot

British journalist, businessman, and essayist (1826-1877)

Walter Bagehot (February 3 1826 – March 24 1877) was an English businessman, essayist and journalist who wrote about literature, government and economics.

Quotes

editShakespeare—the Man (1853)

edit- The reason why so few good books are written is, that so few people who can write know anything. In general an author has always lived in a room, has read books, has cultivated science, is acquainted with the style and sentiments of the best authors, but he is out of the way of employing his own eyes and ears. He has nothing to hear and nothing to see. His life is a vacuum.

- Morgan, Forrest, ed (1891). "Shakespeare—the Man, published in the Prospective Review, July 1853". The works of Walter Bagehot. vol. 1. Hartford, Connecticut: Travelers Insurance Company. pp. 265–266 of 255–302.

- Behind every man's external life, which he leads in company, there is another which he leads alone, and which he carries with him apart. We see but one aspect of our neighbor, as we see but one side of the moon; in either case there is also a dark half, which is unknown to us.

- Morgan, Forrest, ed (1891). "Shakespeare—the Man". The works of Walter Bagehot. vol. 1. pp. 280 of 255–302.

- The worst families are those in which the members never really speak their minds to one another; they maintain an atmosphere of unreality, and everyone always lives in an atmosphere of suppressed ill-feeling.

- Ratcliffe, Susan, ed (2007). "Family". Oxford Dictionary of Quotations and Proverbs. NYC, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 105.

Edward Gibbon (1856)

edit- Whatever may be the defects of Gibbon's history, none can deny him a proud precision and a style in marching order.

- (January 1856)"ART. I—Edward Gibbon". National Review 2: 1–42. (quote p. 28)

- ... Practical people have little idea of the practical ability required to write a large book, and especially a large history. Long before you get to the pen, there is an immensity of pure business: heaps of material are strewn every where; but they lie in disorder, unread, uncatalogued, unknown. It seems a dreary waste of life to be analysing, indexing, extracting works and passages, in which one per cent of the contents are interesting, and not half of that per centage will ultimately appear in the flowing narrative.

- (January 1856)"ART. I—Edward Gibbon". National Review 2: 1–42. (quote p. 29)

- ... The fame of Gibbon is highest among writers; those especially who have studied for years particular periods included in his theme (and how many those are; for in the East and West he has set his mark on all that is great for ten centuries!) acutely feel and admiringly observe how difficult it would be to say so much, and leave so little untouched ; to compress so many telling points; to present in so few words so apt and embracing a narrative of the whole.

- (January 1856)"ART. I—Edward Gibbon". National Review 2: 1–42. (quote p. 31)

John Milton (1859)

edit- ... For ancient heroes the exhaustive method is possible: all that can be known of them is contained in a few short passages of Greek and Latin, and it is quite possible to say whatever can be said about every one of these; the result would not be unreasonably bulky, though it might be dull. But in the case of men who have lived in the thick of the crowded modern world, no such course is admissible; overmuch may be said, and we must choose what we will say. Biographers, however, are rarely bold enough to adopt the selective method consistently. They have, we suspect, the fear of the critics before their eyes.

- (July 1859)"ART. VII—John Milton". National Review 9: 150–186. (quote from p. 151)

- ... Nothing is so simple as the subject matter of his works. The two greatest of his creations, the character of Satan and the character of Eve, are two of the simplest—the latter probably the very simplest—in the whole field of literature. On this side, Milton's art is classical. On the other hand, in no writer is the imagery more profuse, the illustrations more various, the dress altogether more splendid; and in this respect the style of his art seems romantic and modern. In real truth, however, it is only ancient art in a modern disguise: the dress is a mere dress, and can be stripped off when we will.—we all of us do perhaps in memory strip it off for ourselves.

- (July 1859)"ART. VII—John Milton". National Review 9: 150–186. (quote from p. 174)

- ... Satan is made interesting. This has been the charge of a thousand orthodox and even heterodox writers against Milton.

- (July 1859)"ART. VII—John Milton". National Review 9: 150–186. (quote from p. 179)

The English Constitution (1867)

edit- A political country is like an American forest; you have only to cut down the old trees, and immediately new trees come up to replace them.

- But the mass of the old electors did not analyse very much: they liked to have one of their "betters" to represent them; if he was rich they respected him much; and if he was a lord, they liked him the better. The issue put before these electors was, which of two rich people will you choose? And each of those rich people was put forward by great parties whose notions were the notions of the rich—whose plans were their plans. The electors only selected one or two wealthy men to carry out the schemes of one or two wealthy associations.

- Introduction, p. xiii

- The "old electors" Bagehot refers to were the £10 borough householders enfranchised by the Reform Act of 1832.

- In excited states of the public mind they have scarcely a discretion at all; the tendency of the public perturbation determines what shall and what shall not be dealt with. But, upon the other hand, in quiet times statesmen have great power; when there is no fire lighted, they can settle what fire shall be lit. And as the new suffrage is happily to be tried in a quiet time, the responsibility of our statesmen is great because their power is great too.

- A cabinet is a combining committee,—a hyphen which joins, a buckle which fastens, the legislative part of the state to the executive part of the state. In its origin it belongs to the one, in its functions it belongs to the other.

- Cabinet governments educate the nation; the presidential does not educate it, and may corrupt it.

- Under a cabinet constitution at a sudden emergency this people can choose a ruler for the occasion. It is quite possible and even likely that he would not be ruler before the occasion. The great qualities, the imperious will, the rapid energy, the eager nature fit for a great crisis are not required—are impediments—in common times. A Lord Liverpool is better in everyday politics than a Chatham—a Louis Philippe far better than a Napoleon. By the structure of the world we want, at the sudden occurrence of a grave tempest, to change the helmsman—to replace the pilot of the calm by the pilot of the storm.

- But the Queen has no such veto; She must sign her own death-warrant if the two Houses unanimously send it up to her.

- The Sovereign has, under a constitutional monarchy such as ours, three rights—the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, the right to warn.

- Nations touch at their summits.

- Whatever expenditure is sanctioned—even when it is sanctioned against the ministry's wish—the ministry must find the money. Accordingly, they have the strongest motive to oppose extra outlay.... The ministry is (so to speak) the breadwinner of the political family, and has to meet the cost of philanthropy and glory; just as the head of a family has to pay for the charities of his wife and the toilette of his daughters.

- The caucus is a sort of representative meeting which sits voting and voting till they have cut out all the known men against whom much is to be said, and agreed on some unknown man against whom there is nothing known, and therefore nothing to be alleged.

- No. V, The House of Commons, p. 155

- Bagehot was commenting on the method of selecting Presidential candidates in the United States.

- Free government is self-government. A government of the people by the people. The best government of this sort is that which the people think best.

- The greatest enjoyment possible to man was that which this philosophy promises its votaries—the pleasure of being always right, and always reasoning—without ever being bound to look at anything.

- No. VII, Its Supposed Checks and Balances, p. 250

- From SHAKESPEARE: THE INDIVIDUAL, quote attributed to Bagehot says: "The greatest pleasure in life is doing what other people say you cannot do."

Physics and Politics (1869)

edit- The great difficulty which history records is not that of the first step, but that of the second step. What is most evident is not the difficulty of getting a fixed law, but getting out of a fixed law; not of cementing (as upon a former occasion I phrased it) a cake of custom, but of breaking the cake of custom; not of making the first preservative habit, but of breaking through it, and reaching something better.

- Ch. 2, The Use of Conflict

- "Maternity," it has been said, "is a matter of fact, paternity is a matter of opinion."

- One of the greatest pains to human nature is the pain of a new idea.

- Ch. 5, The Age of Discussion

- All the inducements of early society tend to foster immediate action; all its penalties fall on the man who pauses; the traditional wisdom of those times was never weary of inculcating that "delays are dangerous," and that the sluggish man — the man "who roasteth not that which he took in hunting" — will not prosper on the earth, and indeed will very soon perish out of it. And in consequence an inability to stay quiet, an irritable desire to act directly, is one of the most conspicuous failings of mankind.

- Ch. 5

- I wish the art of benefiting men had kept pace with the art of destroying them; for though war has become slow, philanthropy has remained hasty. The most melancholy of human reflections, perhaps, is that, on the whole, it is a question whether the, benevolence of mankind does most good or harm. Great good, no doubt, philanthropy does, but then it also does great evil. It augments so much vice, it multiplies so much suffering, it brings to life such great populations to suffer and to be vicious, that it is open to argument whether it be or be not an evil to the world, and this is entirely because excellent people fancy that they can do much by rapid action — that they will most benefit the world when they most relieve their own feelings; that as soon as an evil is seen "something" ought to be done to stay and prevent it.

- Ch. 5

- Most men of business think "Anyhow this system will probably last my time. It has gone on a long time, and is likely to go on still."

- Ch. I, Introductory

- Credit means that a certain confidence is given, and a certain trust reposed. Is that trust justified? and is that confidence wise? These are the cardinal questions. To put it more simply credit is a set of promises to pay; will those promises be kept?

- Ch. II, A General View of Lombard Street

- The less money lying idle the greater is the dividend.

- Ch. II, A General View of Lombard Street

- The best way for the bank or banks who have the custody of the bank reserve to deal with a drain arising from internal discredit, is to lend freely. The first instinct of everyone is the contrary. There being a large demand on a fund which you want to preserve, the most obvious way to preserve it is to hoard it—to get in as much as you can, and to let nothing go out which you can help. But every banker knows that this is not the way to diminish discredit. This discredit means, 'an opinion that you have not got any money,' and to dissipate that opinion, you must, if possible, show that you have money: you must employ it for the public benefit in order that the public may know that you have it.

- Ch. II, A General View of Lombard Street

- The owners of savings not finding, in adequate quantities, their usual kind of investments, rush into anything that promises speciously, and when they find that these specious investments can be disposed of at a high profit, they rush into them more and more. The first taste is for high interest, but that taste soon becomes secondary. There is a second appetite for large gains to be made by selling the principal which is to yield the interest. So long as such sales can be effected the mania continues; when it ceases to be possible to effect them, ruin begins.

- Ch. VI, Why Lombard Street Is Often Very Dull, and Sometimes Extremely Excited

- The name ‘London Banker’ had especially a charmed value. He was supposed to represent, and often did represent, a certain union of pecuniary sagacity and educated refinement which was scarcely to be found in any other part of society.

- Ch. X, The Private Banks

Literary Studies (1879)

edit- To a great experience one thing is essential — an experiencing nature.

- The purse strings tie us to our kind.

- The reason why so few good books are written is, that so few people that can write know anything. In general an author has always lived in a room, has read books, has cultivated science, is acquainted with the style and sentiments of the best authors, but he is out of the way of employing his own eyes and ears. He has nothing to hear and nothing to see. His life is a vacuum.

- Shakespeare

- A highly developed moral nature joined to an undeveloped intellectual nature, an undeveloped artistic nature, and a very limited religious nature, is of necessity repulsive. It represents a bit of human nature — a good bit, of course, but a bit only — in disproportionate, unnatural and revolting prominence.

- Wordsworth, Tennyson and Browning

- The Ethiop gods have Ethiop lips,

Bronze cheeks, and woolly hair;

The Grecian gods are like the Greeks,

As keen-eyed, cold and fair.- Literary Studies, II. 410. "Ignorance of Man".

Biographical Studies (1907)

edit- A constitutional statesman is in general a man of common opinions and uncommon abilities.

- You may talk of the tyranny of Nero and Tiberius; but the real tyranny is the tyranny of your next-door neighbor... Public opinion is a permeating influence, and it exacts obedience to itself; it requires us to think other men's thoughts, to speak other men's words, to follow other men's habits.

- Sir Robert Peel

- It is good to be without vices, but it is not good to be without temptations.

- [Of Guizot] A Puritan born in France by mistake.

Walter Scott : The Critical Heritage (1970)

edit- In truth, poverty is an anomaly to rich people. It is very difficult to make out why people who want dinner do not ring the bell.

- Chapter: Walter Bagehot on Scott National Review 1858, p404

The Life of Walter Bagehot (Biography by Emily Barrington, 1914)

edit- Every trouble in life is a joke compared to madness.

- This biography relates that Bagehot's "mother was at times insane", and that this fact was "the iron that entered into [Bagehot's] soul." Emily Barrington (1914). The Life of Walter Bagehot.

Misattributed

edit- Honor sinks where commerce long prevails.

- Where wealth and freedom reign, contentment fails,

And honor sinks, where commerce long prevails.

— Oliver Goldsmith, "The Traveller; or, a Prospect of Society'" (1764). This quote can be found on the Oliver Goldsmith page.

- Where wealth and freedom reign, contentment fails,