Untimely Meditations

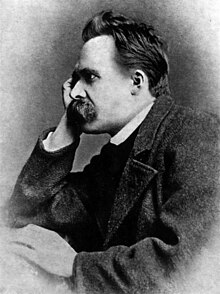

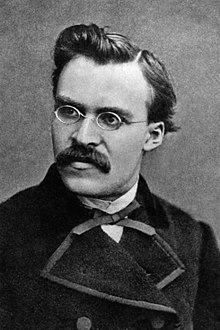

essay by Friedrich Nietzsche

Untimely Meditations (German: Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen) consists of four essays by Friedrich Nietzsche, composed between 1873 and 1876.

David Strauss, the Confessor and the Writer

edit- as translated by A. Ludovici

- Mag wohl die Verwechselung in jenem Wahne des Bildungsphilisters daher rühren, dass er überall das gleichförmige Gepräge seiner selbst wiederfindet und nun aus diesem gleichförmigen Gepräge aller „Gebildeten” auf eine Stileinheit der deutschen Bildung, kurz auf eine Kultur schliesst.

- The confusion underlying the Culture-Philistine’s error may arise from the fact that, since he comes into contact everywhere with creatures cast in the same mould as himself, he concludes that this uniformity among all “scholars” must point to a certain uniformity in German education—hence to culture.

- Eine unglückliche Verdrehung muss im Gehirne des gebildeten Philisters vor sich gegangen sein: er hält gerade das, was die Kultur verneint, für die Kultur.

- The mind of the cultured Philistine must have become sadly unhinged; for precisely what culture repudiates he regards as culture itself.

- Nobody, however, is more disliked by [the Culture-Philistine] than the man who regards him as a Philistine, and tells him what he is—namely, the barrier in the way of all powerful men and creators, the labyrinth for all who doubt and go astray, the swamp for all the weak and the weary, the fetters of those who would run towards lofty goals, the poisonous mist that chokes all germinating hopes, the scorching sand to all those German thinkers who seek for, and thirst after, a new life. For the mind of Germany is seeking; and you hate it because it is seeking, and because it will not accept your word when you declare that you have found what it is seeking.

- In order to be able thus to misjudge, and thus to grant left-handed veneration to our classics, people must have ceased to know them. This, generally speaking, is precisely what has happened. For, otherwise, one ought to know that there is only one way of honoring them, and that is to continue seeking with the same spirit and with the same courage, and not to weary of the search. But to foist the doubtful title of “classics” upon them, and to “edify” oneself from time to time by reading their works, means to yield to those feeble and selfish emotions which all the paying public may purchase at concert-halls and theatres. Even the raising of monuments to their memory, and the christening of feasts and societies with their names—all these things are but so many ringing cash payments by means of which the Culture-Philistine discharges his indebtedness to them, so that in all other respects he may be rid of them, and, above all, not bound to follow in their wake and prosecute his search further. For henceforth inquiry is to cease: that is the Philistine watchword.

- [The Philistine] opposed the restless creative spirit that animates the artist, by means of a certain smug ease—the ease of self-conscious narrowness, tranquility, and self-sufficiency. His tapering finger pointed, without any affectation of modesty, to all the hidden and intimate incidents of his life, to the many touching and ingenuous joys which sprang into existence in the wretched depths of his uncultivated existence.

- These smug ones [The Philistines] now once and for all sought to escape from the yoke of these dubious classics and the command which they contained—to seek further and to find.

- [The Philistines] only devised the notion of an epigone-age in order to secure peace for themselves, and to be able to reject all the efforts of disturbing innovators summarily as the work of epigones. With the view of ensuring their own tranquility, these smug ones even appropriated history, and sought to transform all sciences that threatened to disturb their wretched ease into branches of history... No, in their desire to acquire an historical grasp of everything, stultification became the sole aim of these philosophical admirers of “nil admirari.” While professing to hate every form of fanaticism and intolerance, what they really hated, at bottom, was the dominating genius and the tyranny of the real claims of culture.

- In this way, a philosophy which veiled the Philistine confessions of its founder beneath neat twists and flourishes of language proceeded further to discover a formula for the canonization of the commonplace. It expatiated upon the rationalism of all reality, and thus ingratiated itself with the Culture-Philistine, who also loves neat twists and flourishes, and who, above all, considers himself real, and regards his reality as the standard of reason for the world. From this time forward he began to allow every one, and even himself, to reflect, to investigate, to aestheticise, and, more particularly, to make poetry, music, and even pictures—not to mention systems of philosophy; provided, of course, that ... no assault were made upon the “reasonable” and the “real”—that is to say, upon the Philistine.

- Here Nietzsche is talking about David Strauss, but he later applies essentially the same criticism to the British empiricists.

On the uses and disadvantages of history for life

edit- as translated by R. J. Hollingdale

- “I hate everything that merely instructs me without augmenting or directly invigorating my activity.” These words are from Goethe and they may stand as a sincere ceterum censeo at the beginning of our meditation on the value of history. For its intention is to show why instruction without invigoration, why knowledge not attended by action, why history as a costly superfluity and luxury, must, to use Goethe's word, be seriously hated by us—hated because we still lack even the things we need and the superfluous is the enemy of the necessary.

- We need history, certainly, but we need it for reasons different from those for which the idler in the garden of knowledge needs it, even though he may look nobly down on our rough and charmless needs and requirements. We need it, that is to say, for the sake of life and action, not so as to turn comfortably away from life and action, let alone for the purpose of extenuating the self seeking life and the base and cowardly action. We want to serve history only to the extent that history serves life: for it is possible to value the study of history to such a degree that life becomes stunted and degenerate.

- Ich wüsste nicht, was die classische Philologie in unserer Zeit für einen Sinn hätte, wenn nicht den, in ihr unzeitgemäss—das heisst gegen die Zeit und dadurch auf die Zeit und hoffentlich zu Gunsten einer kommenden Zeit—zu wirken.

- I do not know what meaning classical studies could have for our time if they were not untimely—that is to say, acting counter to our time and thereby acting on our time and, let us hope, for the benefit of a time to come.

Schopenhauer as Educator

edit- as translated by R. J. Hollingdale

- Im Grunde weiß jeder Mensch recht wohl, daß er nur einmal, als ein Unikum, auf der Welt ist und daß kein noch so seltsamer Zufall zum zweitenmal ein so wunderlich buntes Mancherlei zum Einerlei, wie er es ist, zusammenschütteln wird: er weiß es, aber verbirgt es wie ein böses Gewissen – weshalb? Aus Furcht vor dem Nachbar, welcher die Konvention fordert und sich selbst mit ihr verhüllt.

- In his heart every man knows quite well that, being unique, he will be in the world only once and that no imaginable chance will for a second time gather together into a unity so strangely variegated an assortment as he is: he knows it but he hides it like a bad conscience—why? From fear of his neighbor, who demands conventionality and cloaks himself with it.

- Was ist es, was den einzelnen zwingt, den Nachbar zu fürchten, herdenmäßig zu denken und zu handeln und seiner selbst nicht froh zu sein? Schamhaftigkeit vielleicht bei einigen und seltnen. Bei den allermeisten ist es Bequemlichkeit, Trägheit, kurz jener Hang zur Faulheit, von dem der Reisende sprach.

- What is it that constrains the individual to fear his neighbor, to think and act like a member of a herd, and to have no joy in himself? Modesty, perhaps, in a few rare cases. With the great majority it is indolence, inertia.

- Die Menschen sind noch fauler als furchtsam und fürchten gerade am meisten die Beschwerden, welche ihnen eine unbedingte Ehrlichkeit und Nacktheit aufbürden würde. Die Künstler allein hassen dieses lässige Einhergehen in erborgten Manieren und übergehängten Meinungen und enthüllen das Geheimnis, das böse Gewissen von jedermann, den Satz, daß jeder Mensch ein einmaliges Wunder ist.

- Men are even lazier than they are timid, and fear most of all the inconveniences with which unconditional honesty and nakedness would burden them. Artists alone hate this sluggish promenading in borrowed fashions and appropriated opinions and they reveal everyone’s secret bad conscience, the law that every man is a unique miracle.

- When the great thinker despises mankind, he despises its laziness: for it is on account of their laziness that men seem like factory products.

- A man who would not belong in the mass needs only to cease being comfortable with himself.

- The man who does not wish to belong to the mass needs only to cease taking himself easily; let him follow his conscience, which calls to him: “Be your self! All you are now doing, thinking, desiring, is not you yourself.”

- Es gibt kein öderes und widrigeres Geschöpf in der Natur als den Menschen, welcher seinem Genius ausgewichen ist und nun nach rechts und nach links, nach rückwärts und überallhin schielt. Man darf einen solchen Menschen zuletzt gar nicht mehr angreifen, denn er ist ganz Außenseite ohne Kern, ein anbrüchiges, gemaltes, aufgebauschtes Gewand.

- There exists no more repulsive and desolate creature in the world than the man who has evaded his genius and who now looks furtively to left and right, behind him and all about him. ... He is wholly exterior, without kernel, a tattered, painted bag of clothes.

- If it is true to say of the lazy that they kill time, then it is greatly to be feared that an era which sees its salvation in public opinion, this is to say private laziness, is a time that really will be killed: I mean that it will be struck out of the history of the true liberation of life. How reluctant later generations will be to have anything to do with the relics of an era ruled, not by living men, but by pseudo-men dominated by public opinion.

- Wir haben uns über unser Dasein vor uns selbst zu verantworten; folglich wollen wir auch die wirklichen Steuermänner dieses Daseins abgeben und nicht zulassen, daß unsre Existenz einer gedankenlosen Zufälligkeit gleiche.

- We are responsible to ourselves for our own existence; consequently we want to be the true helmsmen of this existence and refuse to allow our existence to resemble a mindless act of chance.

- I will make an attempt to attain freedom, the youthful soul says to itself; and is it to be hindered in this by the fact that two nations happen to hate and fight one another, or that two continents are separated by an ocean, or that all around it a religion is taught with did not yet exist a couple of thousand years ago. All that is not you, it says to itself.

- Niemand kann dir die Brücke bauen, auf der gerade du über den Fluß des Lebens schreiten mußt, niemand außer dir allein.

- No one can construct for you the bridge upon which precisely you must cross the stream of life, no one but you yourself alone.

- Es gibt in der Welt einen einzigen Weg, auf welchem niemand gehen kann, außer dir: wohin er führt? Frage nicht, gehe ihn.

- There exists in the world a single path along which no one can go except you: whither does it lead? Do not ask, go along it.

- Wie finden wir uns selbst wieder? Wie kann sich der Mensch kennen? Er ist eine dunkle und verhüllte Sache; und wenn der Hase sieben Häute hat, so kann der Mensch sich sieben mal siebzig abziehn und wird noch nicht sagen können: »das bist du nun wirklich, das ist nicht mehr Schale«.

- How can a man know himself? He is a thing dark and veiled; and if the hare has seven skins, man can slough off seventy times seven and still not be able to say: “this is really you, this is no longer outer shell.”

- Das ist das Geheimnis aller Bildung: sie verleiht nicht künstliche Gliedmaßen, wächserne Nasen, bebrillte Augen – vielmehr ist das, was diese Gaben zu geben vermöchte, nur das Afterbild der Erziehung. Sondern Befreiung ist sie, Wegräumung alles Unkrauts, Schuttwerks, Gewürms, das die zarten Keime der Pflanzen antasten will.

- That is the secret of all culture: it does not provide artificial limbs, wax noses or spectacles—that which can provide these things is, rather, only sham education. Culture is liberation, the removal of all the weeds, rubble and vermin that want to attack the tender buds of the plant.

- The reference to artificial limbs and wax noses derived from Schopenhauer: "Truth that has been merely learned is like an artificial limb, a false tooth, a waxen nose; at best, like a nose made out of another’s flesh; it adheres to us only because it is put on. But truth acquired by thinking of our own is like a natural limb; it alone really belongs to us. This is the fundamental difference between the thinker and the mere man of learning." From: “On Thinking for Oneself,” Parerga und Paralipomena, Vol. 2, § 260

- Die gebildeten Stände und Staaten werden von einer großartig verächtlichen Geldwirtschaft fortgerissen. Niemals war die Welt mehr Welt, nie ärmer an Liebe und Güte.

- The civilized classes and nations are swept away by the grand rush for contemptible wealth. Never was the world worldlier, never was it emptier of love and goodness.

- Where there have been powerful governments, societies, religions, public opinions, in short wherever there has been tyranny, there the solitary philosopher has been hated; for philosophy offers an asylum to a man into which no tyranny can force it way, the inward cave, the labyrinth of the heart.

- All that exists that can be denied deserves to be denied; and being truthful means: to believe in an existence that can in no way be denied and which is itself true and without falsehood.

- The objective of all human arrangements is through distracting one’s thoughts to cease to be aware of life.

- Haste is universal because everyone is in flight from himself.