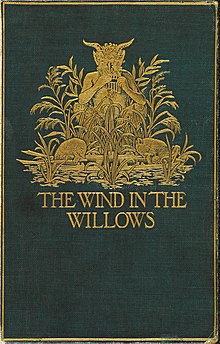

The Wind in the Willows

The Wind in the Willows is a classic children's novel by the British novelist Kenneth Grahame, first published in 1908. It details the story of Mole, Ratty, and Badger as they try to help Mr. Toad, after he becomes obsessed with motorcars and gets into trouble. It also details short stories about them that are disconnected from the main narrative. The novel was based on bedtime stories Grahame told his son Alastair. It has been adapted numerous times for both stage and screen.

The Wind in the Willows received negative reviews upon its initial release, but it has since become a classic of British literature. It was listed at No. 16 in the BBC's survey The Big Read and has been adapted multiple times in different media.

Quotes

editCh. I: "The River Bank"

edit- The Mole had been working very hard all the morning, spring-cleaning his little home. First with brooms, then with dusters; then on ladders and steps and chairs, with a brush and a pail of whitewash; till he had dust in his throat and eyes, and splashes of whitewash all over his black fur, and an aching back and weary arms. Spring was moving in the air above and in the earth below and around him, penetrating even his dark and lowly little house with its spirit of divine discontent and longing. It was small wonder, then, that he suddenly flung down his brush on the floor, said “Bother!” and “O blow!” and also “Hang spring-cleaning!” and bolted out of the house without even waiting to put on his coat.

- Opening lines

- After all, the best part of a holiday is perhaps not so much to be resting yourself, as to see all the other fellows busy working.

- There is nothing — absolutely nothing — half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats. In or out of ‘em, it doesn’t matter. Nothing seems really to matter, that’s the charm of it. Whether you get away, or whether you don’t; whether you arrive at your destination or whether you reach somewhere else, or whether you never get anywhere at all, you’re always busy, and you never do anything in particular; and when you’ve done it there’s always something else to do.

- Rat

- 'I beg your pardon,' said the Mole, pulling himself together with an effort. 'You must think me very rude; but all this is so new to me. So — this — is — a — River!'

'The River,' corrected the Rat.

- 'Weasels — and stoats — and foxes — and so on. They're all right in a way — I'm very good friends with them — pass the time of day when we meet, and all that — but they break out sometimes, there's no denying it, and then — well, you can't really trust them, and that's the fact.'

- Rat

Through the rushes tall,

Ducks are a-dabbling,

Up tails all!

- 'Beyond the Wild Wood comes the Wide World,' said the Rat. 'And that's something that doesn't matter, either to you or me. I've never been there, and I'm never going, nor you either, if you've got any sense at all.

Ch, II: "The Open Road"

edit- All along the backwater,

Through the rushes tall,

Ducks are a-dabbling,

Up tails all!- 'Ducks’ Ditty', composed by Rat

- Here today, up and off to somewhere else tomorrow! Travel, change, interest, excitement! The whole world before you, and a horizon that's always changing!

- Glorious, stirring sight! The poetry of motion! The real way to travel! The only way to travel! Here today — in next week tomorrow! Villages skipped, towns and cities jumped — always somebody else’s horizon! O bliss! O poop-poop! O my! O my!

- Toad

- Toad talked big about all he was going to do in the days to come, while stars grew fuller and larger all around them, and a yellow moon, appearing suddenly and silently from nowhere in particular, came to keep them company and listen to their talk.

- Somehow, it soon seemed taken for granted by all three of them that the trip was a settled thing; and the Rat, though still unconvinced in his mind, allowed his good-nature to over-ride his personal objections.

- A careful inspection showed them that, even if they succeeded in righting it by themselves, the cart would travel no longer. The axles were in a hopeless state, and the missing wheel was shattered into pieces.

- It's never the wrong time to call on Toad. Early or late he's always the same fellow. Always good-tempered, always glad to see you, always sorry when you go!

Ch. III: "The Wild Wood"

edit- The pageant of the river bank had marched steadily along, unfolding itself in scene-pictures that succeeded each other in stately procession. Purple loosestrife arrived early, shaking luxuriant tangled locks along the edge of the mirror whence its own face laughed back at it. Willow-herb, tender and wistful, like a pink sunset cloud, was not slow to follow. Comfrey, the purple hand-in-hand with the white, crept forth to take its place in the line; and at last one morning the diffident and delaying dog-rose stepped delicately on the stage, and one knew, as if string-music had announced it in stately chords that strayed into a gavotte, that June at last was here. One member of the company was still awaited; the shepherd-boy for the nymphs to woo, the knight for whom the ladies waited at the window, the prince that was to kiss the sleeping summer back to life and love. But when meadow-sweet, debonair and odorous in amber jerkin, moved graciously to his place in the group, then the play was ready to begin.

- The Mole had long wanted to make the acquaintance of the Badger. He seemed, by all accounts, to be such an important personage and, though rarely visible, to make his unseen influence felt by everybody about the place.

- Badger hates Society, and invitations, and dinner, and all that sort of thing.

- The whole wood seemed running now, running hard, hunting, chasing, closing in round something or — somebody? In panic, he began to run too, aimlessly, he knew not whither.

Ch. IV: "Mr. Badger"

edit- No animal, according to the rules of animal etiquette, is ever expected to do anything strenuous, or heroic, or even moderately active during the off-season of winter.

- There was the noise of a bolt shot back, and the door opened a few inches, enough to show a long snout and a pair of sleepy blinking eyes.

- Animals arrived, liked the look of the place, took up their quarters, settled down, spread, and flourished. They didn't bother themselves about the past — they never do; they're too busy.

- The Wild Wood is pretty well populated by now; with all the usual lot, good, bad, and indifferent — I name no names. It takes all sorts to make a world.

- 'I see you don't understand, and I must explain it to you. Well, very long ago, on the spot where the Wild Wood waves now, before ever it had planted itself and grown up to what it now is, there was a city — a city of people, you know. Here, where we are standing, they lived, and walked, and talked, and slept, and carried on their business. Here they stabled their horses and feasted, from here they rode out to fight or drove out to trade. They were a powerful people, and rich, and great builders. They built to last, for they thought their city would last for ever.'

'But what has become of them all?' asked the Mole.

'Who can tell?' said the Badger. 'People come — they stay for a while, they flourish, they build — and they go. It is their way. But we remain. There were badgers here, I've been told, long before that same city ever came to be. And now there are badgers here again. We are an enduring lot, and we may move out for a time, but we wait, and are patient, and back we come. And so it will ever be.'

Ch. V: "Dulce Domum (Sweetly Homeward)"

edit- We others, who have long lost the more subtle of the physical senses, have not even proper terms to express an animal’s inter-communications with his surroundings, living or otherwise, and have only the word “smell,” for instance, to include the whole range of delicate thrills which murmur in the nose of the animal night and day, summoning, warning, inciting, repelling.

- It was one of these mysterious fairy calls from out the void that suddenly reached Mole in the darkness, making him tingle through and through with its very familiar appeal, even while yet he could not clearly remember what it was. He stopped dead in his tracks, his nose searching hither and thither in its efforts to recapture the fine filament, the telegraphic current, that had so strongly moved him. A moment, and he had caught it again; and with it this time came recollection in fullest flood.

Home! That was what they meant, those caressing appeals, those soft touches wafted through the air, those invisible little hands pulling and tugging, all one way! Why, it must be quite close by him at that moment, his old home that he had hurriedly forsaken and never sought again, that day when he first found the River! And now it was sending out its scouts and its messengers to capture him and bring him in.

- He saw clearly how plain and simple—how narrow, even—it all was; but clearly, too, how much it all meant to him, and the special value of some such anchorage in one’s existence. He did not at all want to abandon the new life and its splendid spaces, to turn his back on sun and air and all they offered him and creep home and stay there; the upper world was all too strong, it called to him still, even down there, and he knew he must return to the larger stage. But it was good to think he had this to come back to, this place which was all his own, these things which were so glad to see him again and could always be counted upon for the same simple welcome.

Ch. VI: "Mr. Toad"

edit- Animals when in company walk in a proper and sensible manner, in single file, instead of sprawling all across the road and being of no use or support to each other in case of sudden trouble or danger.

- Independence is all very well, but we animals never allow our friends to make fools of themselves beyond a certain limit; and that limit you've reached.

Ch. VII: "The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn"

edit- Dark and deserted as it was, the night was full of small noises, song and chatter and rustling, telling of the busy little population who were up and about, plying their trades and vocations through the night till sunshine should fall on them at last and send them off to their well-earned repose. The water's own noises, too, were more apparent than by day, its gurglings and 'cloops' more unexpected and near at hand; and constantly they started at what seemed a sudden clear call from an actual articulate voice.

- A bird piped suddenly, and was still; and a light breeze sprang up and set the reeds and bulrushes rustling. Rat, who was in the stern of the boat, while Mole sculled, sat up suddenly and listened with a passionate intentness. Mole, who with gentle strokes was just keeping the boat moving while he scanned the banks with care, looked at him with curiosity.

'It's gone!' sighed the Rat, sinking back in his seat again. 'So beautiful and strange and new. Since it was to end so soon, I almost wish I had never heard it. For it has roused a longing in me that is pain, and nothing seems worth while but just to hear that sound once more and go on listening to it for ever. No! There it is again!' he cried, alert once more. Entranced, he was silent for a long space, spellbound.

'Now it passes on and I begin to lose it,' he said presently. 'O Mole! the beauty of it! The merry bubble and joy, the thin, clear, happy call of the distant piping! Such music I never dreamed of, and the call in it is stronger even than the music is sweet! Row on, Mole, row! For the music and the call must be for us.'

The Mole, greatly wondering, obeyed. 'I hear nothing myself,' he said, 'but the wind playing in the reeds and rushes and osiers.'

- 'Clearer and nearer still,' cried the Rat joyously. 'Now you must surely hear it! Ah — at last — I see you do!'

Breathless and transfixed the Mole stopped rowing as the liquid run of that glad piping broke on him like a wave, caught him up, and possessed him utterly. He saw the tears on his comrade's cheeks, and bowed his head and understood.

- On either side of them, as they glided onwards, the rich meadow-grass seemed that morning of a freshness and a greenness unsurpassable. Never had they noticed the roses so vivid, the willow-herb so riotous, the meadow-sweet so odorous and pervading. Then the murmur of the approaching weir began to hold the air, and they felt a consciousness that they were nearing the end, whatever it might be, that surely awaited their expedition.

- In midmost of the stream, embraced in the weir's shimmering arm-spread, a small island lay anchored, fringed close with willow and silver birch and alder. Reserved, shy, but full of significance, it hid whatever it might hold behind a veil, keeping it till the hour should come, and, with the hour, those who were called and chosen.

- Slowly, but with no doubt or hesitation whatever, and in something of a solemn expectancy, the two animals passed through the broken tumultuous water and moored their boat at the flowery margin of the island.

- 'This is the place of my song-dream, the place the music played to me,' whispered the Rat, as if in a trance. 'Here, in this holy place, here if anywhere, surely we shall find Him!'

Then suddenly the Mole felt a great Awe fall upon him, an awe that turned his muscles to water, bowed his head, and rooted his feet to the ground. It was no panic terror — indeed he felt wonderfully at peace and happy — but it was an awe that smote and held him and, without seeing, he knew it could only mean that some august Presence was very, very near. With difficulty he turned to look for his friend and saw him at his side cowed, stricken, and trembling violently. And still there was utter silence in the populous bird-haunted branches around them; and still the light grew and grew.

- Perhaps he would never have dared to raise his eyes, but that, though the piping was now hushed, the call and the summons seemed still dominant and imperious. He might not refuse, were Death himself waiting to strike him instantly, once he had looked with mortal eye on things rightly kept hidden. Trembling he obeyed, and raised his humble head; and then, in that utter clearness of the imminent dawn, while Nature, flushed with fullness of incredible colour, seemed to hold her breath for the event, he looked in the very eyes of the Friend and Helper; saw the backward sweep of the curved horns, gleaming in the growing daylight; saw the stern, hooked nose between the kindly eyes that were looking down on them humourously, while the bearded mouth broke into a half-smile at the corners; saw the rippling muscles on the arm that lay across the broad chest, the long supple hand still holding the pan-pipes only just fallen away from the parted lips; saw the splendid curves of the shaggy limbs disposed in majestic ease on the sward; saw, last of all, nestling between his very hooves, sleeping soundly in entire peace and contentment, the little, round, podgy, childish form of the baby otter. All this he saw, for one moment breathless and intense, vivid on the morning sky; and still, as he looked, he lived; and still, as he lived, he wondered.

- Sudden and magnificent, the sun's broad golden disc showed itself over the horizon facing them; and the first rays, shooting across the level water-meadows, took the animals full in the eyes and dazzled them. When they were able to look once more, the Vision had vanished, and the air was full of the carol of birds that hailed the dawn.

- As they stared blankly in dumb misery deepening as they slowly realised all they had seen and all they had lost, a capricious little breeze, dancing up from the surface of the water, tossed the aspens, shook the dewy roses and blew lightly and caressingly in their faces; and with its soft touch came instant oblivion. For this is the last best gift that the kindly demi-god is careful to bestow on those to whom he has revealed himself in their helping: the gift of forgetfulness. Lest the awful remembrance should remain and grow, and overshadow mirth and pleasure, and the great haunting memory should spoil all the after-lives of little animals helped out of difficulties, in order that they should be happy and lighthearted as before.

- Mole stood still a moment, held in thought. As one wakened suddenly from a beautiful dream, who struggles to recall it, and can re-capture nothing but a dim sense of the beauty of it, the beauty! Till that, too, fades away in its turn, and the dreamer bitterly accepts the hard, cold waking and all its penalties; so Mole, after struggling with his memory for a brief space, shook his head sadly and followed the Rat.

- I feel as if I had been through something very exciting and rather terrible, and it was just over; and yet nothing particular has happened.

- Mole to Rat

- 'Now it is turning into words again — faint but clear — Lest the awe should dwell — And turn your frolic to fret — You shall look on my power at the helping hour — But then you shall forget! Now the reeds take it up — forget, forget, they sigh, and it dies away in a rustle and a whisper. Then the voice returns —

'Lest limbs be reddened and rent — I spring the trap that is set — As I loose the snare you may glimpse me there — For surely you shall forget! Row nearer, Mole, nearer to the reeds! It is hard to catch, and grows each minute fainter.

'Helper and healer, I cheer — Small waifs in the woodland wet — Strays I find in it, wounds I bind in it — Bidding them all forget!- Rat telling Mole of the words he hears in the reeds

- 'But what do the words mean?' asked the wondering Mole.

'That I do not know,' said the Rat simply. 'I passed them on to you as they reached me. Ah! now they return again, and this time full and clear! This time, at last, it is the real, the unmistakable thing, simple — passionate — perfect — '

Ch. VIII: "Toad's Adventures"

edit- Honest Toad was always ready to admit himself in the wrong.

Ch. IX: "Wayfarers All"

edit- There he got out the luncheon-basket and packed a simple meal, in which, remembering the stranger’s origin and preferences, he took care to include a yard of long French bread, a sausage out of which the garlic sang, some cheese which lay down and cried, and a long-necked straw-covered flask wherein lay bottled sunshine shed and garnered on far Southern slopes.

Ch. X: "The Further Adventures Of Toad"

editAs history books have showed;

But never a name to go down to fame

Compared with that of Toad!

- The world has held great Heroes,

As history books have showed;

But never a name to go down to fame

Compared with that of Toad!

- The clever men at Oxford

Know all that there is to be knowed.

But they none of them know one half as much

As intelligent Mr. Toad!

- Free! The word and the thought alone were worth fifty blankets. He was warm from end to end as he thought of the jolly world outside, waiting eagerly for him to make his triumphal entrance, ready to serve him and play up to him, anxious to help him and to keep him company, as it always had been in days of old before misfortune fell upon him.

- 'O, my!' he gasped, as he panted along, 'what an ass I am! What a conceited and heedless ass! Swaggering again! Shouting and singing songs again! Sitting still and gassing again! O my! O my! O my!'

Ch. XI: "Like Summer Tempests Came His Tears"

edit- Well, well, perhaps I am a bit of a talker. A popular fellow such as I am — my friends get round me — we chaff, we sparkle, we tell witty stories — and somehow my tongue gets wagging. I have the gift of conversation. I’ve been told I ought to have a salon, whatever that may be.

- Toad

Ch. XII: "The Return Of Ulysses"

edit- When it began to grow dark, the Rat, with an air of excitement and mystery, summoned them back into the parlour, stood each of them up alongside of his little heap, and proceeded to dress them up for the coming expedition.

- Toad saw that he was trapped. They understood him, they saw through him, they had got ahead of him. His pleasant dream was shattered.

- 'No, not one little song,' replied the Rat firmly, though his heart bled as he noticed the trembling lip of the poor disappointed Toad. 'It's no good, Toady; you know well that your songs are all conceit and boasting and vanity; and your speeches are all self-praise and — and — well, and gross exaggeration and — and — '

'And gas,' put in the Badger, in his common way.

- All the animals cheered when he entered, and crowded round to congratulate him and say nice things about his courage, and his cleverness, and his fighting qualities; but Toad only smiled faintly, and murmured, 'Not at all!' Or, sometimes, for a change, 'On the contrary!'

- He was indeed an altered Toad!

About

edit- One does not argue about The Wind in the Willows. The young man gives it to the girl with whom he is in love, and if she does not like it, asks her to return his letters. The elder man tries it on his nephew, and alters his will accordingly. The book is a test of character. We can't criticize it, because it is criticizing us. As I wrote once: It is a Household Book; a book which everybody in the household loves, and quotes continually; a book which is read aloud to every new guest and is regarded as the touchstone of his worth. When you sit down to it, don't be so ridiculous as to suppose that you are sitting in judgment on my taste, or on the art of Kenneth Grahame. You are merely sitting in judgment on yourself. You may be worthy: I don't know. But it is you who are on trial.

- A. A. Milne, in an Introduction to the Heritage Press edition (New York, 1952)

External links

edit- EBook of The Wind in the Willows

- Free eBook of The Wind in the Willows at Project Gutenberg illustrated by Paul Bransom (1913)