The New Great Game

journalistic term for predicted conflict over central Asian resources

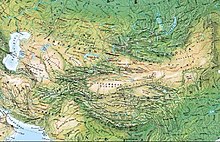

The New Great Game is a term used to describe the conceptualization of modern geopolitics in Central Asia as a competition between regional and world powers for influence, power, hegemony and profits. It is a reference to "the Great Game", the political rivalry between the British and Russian Empires in Central Asia during the 19th century.

— G. Asgar Mitha

Quotes

edit- Control over energy resources [of the former Soviet Union] and export routes out of the Eurasian hinterland is quickly becoming one of the central issues in post-Cold War politics. Like the "Great Game" of the early 20th century, in which the geopolitical interests of the British Empire and Russia clashed over the Caucasus region and Central Asia, today's struggle between Russia and the West may turn on who controls the oil reserves in Eurasia.

- Cohen, Ariel (2006), "The New "Great Game": Oil Politics in the Caucasus and Central Asia", Backgrounder (The Heritage Foundation) (#1065)

- As the war in Afghanistan becomes a mopping-up operation, the US has stepped up troop deployments in the region, in what Russia and China fear is an effort to secure dominant influence over their backyards, a region rich in oil and gas reserves. In the past weeks, diplomats and generals from all three countries have streamed into Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The war on terrorism has turned the Central Asian republics from backwaters into prizes overnight. In a letter to the New York Times last week, former Iraq arms inspector Richard Butler warned that the "Great Game" between Britain and Russia over the Indian sub-continent in the nineteenth century may now be replayed, with Russia and the US as the dominant players. "Now the prize is oil – getting it and transporting it – and Afghanistan is again the contested territory," Butler wrote.

- Helmore, Edward (20 January 2002), US in replay of the 'Great Game', The Observer

- The Great Game is no fun anymore. The term "Great Game" was used by nineteenth-century British imperialists to describe the British-Russian struggle for position on the chessboard of Afghanistan and Central Asia – a contest with a few players, mostly limited to intelligence forays and short wars fought on horseback with rifles, and with those living on the chessboard largely bystanders or victims. More than a century later, the game continues. But now, the number of players has exploded, those living on the chessboard have become involved, and the intensity of the violence and the threats it produces affect the entire globe.

- Rubin, Barnett R.; Rashid, Ahmed (22 September 2008), From Great Game to Grand Bargain: Ending Chaos in Afghanistan and Pakistan

- It is now clear that with the renewed great game, there are more players and more rivalry than it was during the game being played out between Britain and Russia in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In that game there was one winner and one loser. The stakes for which the game is now being played are global supremacy, energy, geo-political security, religion and financial control.

- Asgar Mitha, G. (3 September 2008), The Last Great Game

- Some commentators see the desperate search by countries to acquire commodity-producing firms in other (typically poor, developing) countries as a repeat of the Great Game – the tussle among powers like Britain and Russia for influence in the Middle East and Central Asia during the 19th century. In this view, those that acquire the greatest share of commodity producers early on will enjoy the greatest economic security in the future, as growth in China, India, and other populous developing countries creates shortages of commodity resources. Economic security is the new justification for purchases, such as minority stakes in opaque companies in poorly governed countries, that would otherwise make little business sense.

- Rajan, Raghuram (14 December 2024), "The Great Game Again?", Finance And Development (International Monetary Fund) 43 (4)

- What the U.S. is up to is the 21st century’s version of the "Great Game," the competition that pitted 19th century imperial powers against one another in a bid to control Central Asia and the Middle East. The move to surround Russia and hinder China’s access to energy is part of the Bush Administration’s 2002 "West Point Doctrine," a strategic posture aimed at preventing the rise of any economic or military competitors.

- Hallinan, Conn (7 October 2008), "The Great Game in the Caucasus: Bad Moves by Uncle Sam", Counterpunch

- China is engaged in an anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons drive that has profound implications for future U.S. military strategy in the Pacific. This Chinese ASAT build-up, notable for its assertive testing regime and unexpectedly rapid development as well as its broad scale, has already triggered a cascade of events in terms of U.S. The notion that the U.S. could be caught off-guard in a "space Pearl Harbor" and quickly reduced from an information-age military juggernaut into a disadvantaged industrial-age power in any conflict with China is being taken very seriously by U.S. war planners. As a result, while China’s already impressive ASAT program continues to mature and expand, the U.S. is evolving its own counter-ASAT deterrent as well as its next generation space technology to meet the challenge, and this is leading to a "great game" style competition in outer space.

- Easton, Ian, The Great Game in Space: China’s evolving ASAT Weapons Programs and Their Implications for Future U.S. Strategy, The Project 2049 Institute

- Much copy has been written about the parallels between present geopolitical rivalry in Central Asia and Kipling's "Great Game" between Britain and Russia in the nineteenth century. But it is vital to remember that Britain was interested in the region not for reasons of world hegemony but only because it was ruler of India. Britain's concern was purely defensive, motivated not by a desire to conquer Central Asia but by the fear that Russia would employ the region as a base from which to attack India or to march through Persia to the Gulf to threaten British lines of communication. The same fear lay behind Britain's support for Turkey against Russia, which led to its participation in the Crimean War. No Russian attack on the subcontinent is currently in prospect.

- Lieven, Anatol (2000), "The (Not So) Great Game", The National Interest 22 (58): 69–80

- Although Russia, China, and the United States substantially affect regional security issues, they cannot dictate outcomes the way imperial governments frequently did a century ago. Concerns about a renewed great game are thus exaggerated.

- Weitz, Richard (2006), "Averting a New Great Game in Central Asia", The Washington Quarterly 29 (3): 156

External links

edit- Contessi, Nicola (2013), Central Eurasia and the New Great Game: Players, Moves, Outcomes and Scholarship, Asian Security 9 (3): 231-241, retrieved on 27 September 2015