The Dawn (book)

book by Friedrich Nietzsche

(Redirected from The Dawn)

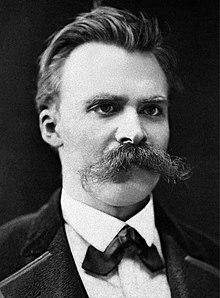

The Dawn or Daybreak: Thoughts on the Prejudices of Morality (German: Morgenröthe: Gedanken über die moralischen Vorurtheile) is a book by Friedrich Nietzsche published in 1881.

Quotes

edit- I descended into the lowest depths, I searched to the bottom, I examined and pried into an old faith on which, for thousands of years, philosophers had built as upon a secure foundation. The old structures came tumbling down about me.

- Preface, H. L. Mencken, trans., cited in The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche (1908), p. 43

- Sittlichkeit ist nichts Anderes (also namentlich nicht mehr!), als Gehorsam gegen Sitten.

- Morality is nothing other (therefore no more!) than obedience to customs.

- § 9

- Morality is nothing other (therefore no more!) than obedience to customs.

- Der freie Mensch ist unsittlich, weil er in Allem von sich und nicht von einem Herkommen abhängen will.

- The free human being is immoral because in all things he is determined to depend upon himself and not upon a tradition.

- § 9

- The free human being is immoral because in all things he is determined to depend upon himself and not upon a tradition.

- In allen ursprünglichen Zuständen der Menschheit bedeutet „böse” so viel wie „individuell”, „frei”, „willkürlich”, „ungewohnt”, „unvorhergesehen”, „unberechenbar”.

- ‘Evil’ signifies the same thing as ‘individual’, ‘free’, ‘capricious’, ‘unusual’, ‘unforeseen’, ‘incalculable.’

- § 9

- ‘Evil’ signifies the same thing as ‘individual’, ‘free’, ‘capricious’, ‘unusual’, ‘unforeseen’, ‘incalculable.’

- If an action is performed not because tradition commands it but for other motives ... even indeed for precisely the motives which once founded the tradition, it is called immoral.

- § 9

- Wer ist der Sittlichste? Einmal Der, welcher das Gesetz am häufigsten erfüllt: also, gleich dem Brahmanen, das Bewusstsein desselben überallhin und in jeden kleinen Zeitteil trägt, sodass er fortwährend erfinderisch ist in Gelegenheiten, das Gesetz zu erfüllen. Sodann Der, der es auch in den schwersten Fällen erfüllt. Der Sittlichste ist Der, welcher am meisten der Sitte opfert: welches aber sind die größten Opfer? Nach der Beantwortung dieser Frage entfalten sich mehrere unterschiedliche Moralen; aber der wichtigste Unterschied bleibt doch jener, welcher die Moralität der häufigsten Erfüllung von der der schwersten Erfüllung trennt. Man täusche sich über das Motiv jener Moral nicht, welche die schwerste Erfüllung der Sitte als Zeichen der Sittlichkeit fordert! Die Selbstüberwindung wird nicht ihrer nützlichen Folgen halber, die sie für das Individuum hat, gefordert, sondern damit die Sitte, das Herkommen herrschend erscheine, trotz allem individuellen Gegengelüst und Vorteil: der Einzelne soll sich opfern,—so heischt es die Sittlichkeit der Sitte.

- Who is the most moral man? First, he who obeys the law most frequently, who ... is continually inventive in creating opportunities for obeying the law. Then, he who obeys it even in the most difficult cases. The most moral man is he who sacrifices the most to custom.... Self-overcoming is demanded, not on account of any useful consequences it may have for the individual, but so that hegemony of custom and tradition shall be made evident.

- R. J. Hollingdale, trans. (1997) § 9

- Who is the most moral man? First, he who obeys the law most frequently, who ... is continually inventive in creating opportunities for obeying the law. Then, he who obeys it even in the most difficult cases. The most moral man is he who sacrifices the most to custom.... Self-overcoming is demanded, not on account of any useful consequences it may have for the individual, but so that hegemony of custom and tradition shall be made evident.

- The moralists who, following in the footsteps of Socrates, offer the individual a morality of self-control and temperance as a means to his own advantage, as his personal way to happiness, are the exceptions. ... They take a new path under the highest disapprobation of all advocates of morality of custom—they cut themselves off from the community, as immoral men, and are in the profoundest sense evil.

- R. J. Hollingdale, trans. (1997) § 9

- Every individual action, every individual mode of thought arouses dread; it is impossible to compute what precisely the rarer, choicer, more original spirits in the whole course of history have had to suffer through being felt as evil and dangerous, indeed through feeling themselves to be so. Under the dominion of the morality of custom, originality of every kind has acquired a bad conscience.

- R. J. Hollingdale, trans. (1997) § 9

- Popular morality and popular medicine. The morality which prevails in a community is constantly being worked at by everybody: most people produce example after example of the alleged relationship between cause and effect between guilt and punishment, confirm it as well founded and strengthen their faith ... All, however, are at one in the wholly crude, unscientific character of their activity ... both material and form are worthless, as are the material and form of all popular medicine. Popular medicine and popular morality belong together and ought not to be evaluated differently as they still are: both are the most dangerous pseudosciences.

- R. J. Hollingdale, trans. (1997) § 11

- Men of application and goodwill, assist in this one work: to take the concept of punishment which has overrun the whole world and root it out! There exists no more noxious weed!

- R. J. Hollingdale, trans. (1997) § 13

- Among barbarous peoples there exists a species of customs whose purpose appears to be [to support the idea of] custom in general: minute and fundamentally superfluous stipulations ... which, however keep continually in the consciousness the constant proximity of custom, the perpetual compulsion to practice customs: so as the strengthen the mighty proposition with which civilization begins: any custom is better than no custom.

- § 16

- Nothing has been purchased more dearly than that little bit of human reason and feeling of freedom that now constitutes our pride. It is this pride, however, which now makes it almost impossible for us to empathize with those tremendous eras of ‘morality of custom’ which precede ‘world history’ as the actual and decisive eras of history which determined the character of mankind: the eras in which suffering counted as virtue, cruelty counted as virtue, dissembling counted as virtue, revenge counted as virtue ... Do you think all this has altered and that mankind must therefore have changed its character?

- § 18

- Custom represents the experiences of men in earlier times, as to what they supposed to be useful and harmful—but the sense for custom (morality) applies, not to these experiences as such, but to the age, sanctity and indiscussability of the custom. And so this sense is a hindrance to the acquisition of new experiences and the correction of customs; that is to say, morality is a hindrance to the creation of new and better customs

- § 19

- Freedoers are at a disadvantage compared to freethinkers because people suffer more obviously from the consequences of deeds than from those of thoughts. If one considers, however, that both one and the other are in search of gratification, and that the in case of the freethinker the mere thinking thorough and enunciation of forbidden things provides this gratification, both are on an equal footing with regard to motive

- § 20

- Whoever has overthrown an existing law of custom has hitherto always first been accounted a bad man: but when, as did happen, the law could not afterwards be reinstantiated and this fact was accepted, the predicate gradually changed—history treats almost exclusively of these bad men who subsequently became good men!

- § 20

- All institutions which accord to a passion belief in its endurance and responsibility for its endurance, contrary to the nature of passion, have raised it to a new rank, and thereafter he who is assailed by such a passion no longer believes himself debased or endangered by it, as he formerly did, but enhanced in his own eyes and those of his peers. Think of institutions and customs which have created out of the fiery abandonment of the moment perpetual fidelity, out of the enjoyment of anger perpetual vengeance, ... out of a single and unpremeditated word perpetual obligation. This transformation has each time introduced a very great deal of hypocrisy and lying into the world, but each time too, and at this cost, it has introduced a new suprahuman concept which elevates mankind.

- § 27

- Here is a morality which rests entirely on the drive to distinction—do not think too highly of it! For what kind of a drive is it, and what thought lies behind it? We want to make the sight of us painful to another and to awaken in him the feeling of envy and of his own impotence and degradation... This person has become humble and is now perfect in his humility—seek for those whom he has for long wished to torture with it! You will find them soon enough! ... The chastity of the nun: with what punitive eyes it looks into the faces of women who live otherwise! How much joy in revenge there is in those eyes! ...the morality of distinction is, in its ultimate foundation, pleasure in refined cruelty.

- § 30

- During the prehistoric age of mankind, spirit was presumed to exist everywhere and was not held in honor as a privilege of man. Because, on the contrary, ... one saw in the spirit that which unites us with nature, not that which sunders us from it.

- § 31

- To suffer for the sake of morality and then be told that this kind of suffering is founded on an error: this arouses indignation. For there is a unique consolation in affirming through one’s suffering a ‘profounder world of truth’ ... and one would much rather suffer and thereby feel oneself exalted above reality (through consciousness of having thus approached this ‘profounder world of truth’) than be without suffering but also without this feeling that one is exalted. It is thus pride, and the customary manner in which pride is gratified, which stands in the way of a new understanding of morality.

- § 32

- Under the pressure of superstitious fear, ... one spoils one’s sense of reality and one’s pleasure in it, and in the end accords reality a value only insofar as it is capable of being a symbol.

- § 33

- Wherever a man’s feelings are exalted, that imaginary world is involved in some way. It is a sad fact, but for the moment the man of science has to be suspicious of all higher feelings, so greatly are they nourished by delusion and nonsense. It is not that they are thus in themselves, or must always remain thus, but of all the gradual purifications awaiting mankind, the purification of the higher feelings will certainly be one of the most gradual.

- § 33

- It is clear that moral feelings are transmitted in this way: children observe in adults inclinations for and aversions to certain actions and, as born apes, imitate these inclinations and aversions; in later life they find themselves full of these acquired and well-exercised affects and consider it only decent to try to account for and justify them. This ‘accounting,’ however, has nothing to do with either the origin or the degree of intensity of the feeling: all one is doing is complying with the rule that, as a rational being, one has to have reasons for one’s For and Against, and that they have to adducible and acceptable reasons.

- § 34

- ‘Trust your feelings!’—But feelings are nothing final or original; behind the feelings there stand judgments and evaluations. ... The inspiration born of feeling is the grandchild of a judgment—and often a false judgment! And in any event not a child of your own! To trust one’s feelings means to give more obedience to one’s grandfather and grandmother and their grandparents than to the gods which are in us: our reason and our experience.

- § 35

- Primitive mankind devised a word. … They had touched on a problem, and by supposing they had solved it they had created a hindrance to its solution.—Now with every piece of knowledge one has to stumble over dead, petrified words.

- § 47

- Men who enjoy moments of exaltation and ecstasy who, on account of the contrast other states present and because of the way they have squandered their nervous energy, are ordinarily in a wretched and miserable condition, regard these moments as their real ‘self’ and their wretchedness and misery as the effect of what is ‘outside the self’; and thus they harbor feelings of revengefulness towards their environment, their age, their entire world.

- § 50

- The free spirit … counts the theory of the innocence of all opinions as being as well founded as the theory of the innocence of all actions

- § 56

- The Christian church … always could, and it can still go wherever it pleases and it always found, and always finds something … to which it can adapt itself and gradually impose upon it a Christian meaning. … One may admire this power of causing the most various elements to coalesce, but one must not forget the contemptible quality that adheres to this power: the astonishing crudeness and self-satisfiedness of the church’s intellect … which permitted it to accept any food and to digest opposites like pebbles.

- § 70

- The [Christian] addition of Hell ... the novel teaching of eternal damnation ... was mightier than the idea of definitive death, which thereafter faded away. It was only science which reconquered (?) it, as it had to do when it at the same time rejected any other idea of death and of any life beyond it.

- § 72

- A proof of truth is not the same thing as a proof of truthfulness.

- § 73

- The passions become evil and malicious if they are regarded as evil and malicious.

- § 76

- Christianity has succeeded in transforming Eros and Aphrodite—great powers capable of idealisation—into diabolical kobolds and phantoms.

- § 76

- Is it not dreadful to make necessary and regularly recurring sensations into a source of inner misery, and in this way to want to make inner misery a necessary and regularly recurring phenomenon.

- § 76

- Must everything that one has to combat, that one has to keep within bounds or on occasion banish totally from one’s mind, always have to be called evil! Is it not the way of common souls always to think an enemy must be evil!

- § 76

- [With] the sexual sensations ... one person, by doing what pleases him, gives pleasure to another person—such benevolent arrangements are not to be found so very often in nature! And to calumniate such an arrangement and to ruin it through associating it with a bad conscience!

- § 76

- Everyone now exclaims loudly against torment inflicted by one person on the body of another ... But we are still far from feeling so decisively and with such unanimity in regard to torments of the soul and how dreadful it is to inflict them. Christianity has made use of them on an unheard-of scale and continues to preach this species of torture

- § 77

- Misfortune and guilt—Christianity has placed these two things on a balance: so that, when misfortune consequent on guilt is great, even now the greatness of the guilt itself is consequently measured by it. ... The Greek tragedy, which speaks so much yet in so different a sense of misfortune and guilt, is a great liberator of the spirit in a way in which the ancients themselves could not feel. They were still so innocent as not to have established an ‘adequate relationship’ between guilt and misfortune. The guilt of their tragic heroes is, indeed, the little stone over which they stumble ... It was reserved for Christianity to say, “Here is a great misfortune and behind it must lie hidden a great, equally great, guilt, even though it may not be clearly visible!

- § 78

- In antiquity there still existed actual misfortune, pure innocent misfortune; only in Christendom did everything become punishment, well-deserved punishment.

- § 78

- With every misfortune, [the Christian] feels himself morally reprehensible and cast out. Poor mankind!

- § 78

- The Greeks have a word for indignation at another’s unhappiness: this affect was inadmissible among Christian peoples and failed to develop, so they also lack a name for this more manly brother of pity.

- § 78

- God created all things except for sin alone: is it any wonder if he is ill-disposed towards it? But man created sin—and is he to cast out this only child of his merely because it displeases God, the grandfather of sin! Is that humane? ... Heart and duty ought to speak firstly for the child and only secondarily for the honor of the grandfather!

- § 81

- Moralism ... is the euthanasia of Christianity.

- § 92

- Unsere Wertschätzungen.—Alle Handlungen gehen auf Wertschätzungen zurück, alle Wertschätzungen sind entweder eigene oder angenommene,—letztere bei Weitem die meisten. Warum nehmen wir sie an? Aus Furcht,—das heißt: wir halten es für ratsamer, uns so zu stellen, als ob sie auch die unsrigen wären—und gewöhnen uns an diese Verstellung, sodass sie zuletzt unsere Natur ist. Eigene Wertschätzung: das will besagen, eine Sache in Bezug darauf messen, wie weit sie gerade uns und niemandem Anderen Lust oder Unlust macht,—etwas äußerst Seltenes!—Aber wenigstens muss doch unsre Wertschätzung des Anderen, in der das Motiv dafür liegt, dass wir uns in den meisten Fällen seiner Wertschätzung bedienen, von uns ausgehen, unsere eigene Bestimmung sein? Ja, aber als Kinder machen wir sie, und lernen selten wieder um; wir sind meist zeitlebens die Narren kindlicher angewöhnter Urteile, in der Art, wie wir über unsre Nächsten (deren Geist, Rang, Moralität, Vorbildlichkeit, Verwerflichkeit) urteilen und es nötig finden, vor ihren Wertschätzungen zu huldigen.

- Our evaluations—All actions may be traced back to evaluations; all evaluations are either original or adopted—the latter being by far the most common. Why do we adopt them? From fear—that is, we consider it more advisable to pretend they are our own—and accustom ourselves to this pretense, so that at length it becomes our own nature. Original evaluation: that is to say, to assess a thing according to the extent to which it pleases or displeases us alone and no one else—something excessively rare!—But must our evaluation of another, in which there lies the motive for our generally availing ourselves of his evaluation, at least not proceed from us, be our own determination? Yes, but we arrive at it as children, and rarely learn to change our view; most of us are our while lives long the fools of the way we acquired in childhood of judging our neighbors (their minds, rank, morality, whether they are exemplary or reprehensible) and of finding it necessary to pay homage to their evaluations.

- § 104 (R. J. Hollingdale, trans.)

- Our evaluations—All actions may be traced back to evaluations; all evaluations are either original or adopted—the latter being by far the most common. Why do we adopt them? From fear—that is, we consider it more advisable to pretend they are our own—and accustom ourselves to this pretense, so that at length it becomes our own nature. Original evaluation: that is to say, to assess a thing according to the extent to which it pleases or displeases us alone and no one else—something excessively rare!—But must our evaluation of another, in which there lies the motive for our generally availing ourselves of his evaluation, at least not proceed from us, be our own determination? Yes, but we arrive at it as children, and rarely learn to change our view; most of us are our while lives long the fools of the way we acquired in childhood of judging our neighbors (their minds, rank, morality, whether they are exemplary or reprehensible) and of finding it necessary to pay homage to their evaluations.

- All our so-called consciousness is a more or less fantastic commentary on an unknown, perhaps unknowable, but felt text.

- § 119, cited in Walter Kauffmann, Nietzsche, p. 182 and p. 268

- Etwas nicht wieder gut zu machen ist: die Vergeudung unserer Jugend, als unsre Erzieher jene wissbegierigen, heißen und durstigen Jahre nicht dazu verwandten, uns der Erkenntnis der Dinge entgegenzuführen, sondern der sogenannten “Klassischen Bildung”! Die Vergeudung unserer Jugend, als man uns ein dürftiges Wissen um Griechen und Römer und deren Sprachen ebenso ungeschickt, als quälerisch beibrachte und zuwider dem obersten Satze aller Bildung: dass man nur Dem, der Hunger darnach hat, eine Speise gebe! Als man uns Mathematik und Physik auf eine gewaltsame Weise aufzwang, anstatt uns erst in die Verzweiflung der Unwissenheit zu führen und unser kleines tägliches Leben, unsere Hantierungen und Alles, was sich zwischen Morgen und Abend im Hause, in der Werkstatt, am Himmel, in der Landschaft begibt, in Tausende von Problemen aufzulösen, von peinigenden, beschämenden, aufreizenden Problemen,—um unsrer Begierde dann zu zeigen, dass wir ein mathematisches und mechanisches Wissen zu allernächst nötig haben und uns dann das erste wissenschaftliche Entzücken an der absoluten Folgerichtigkeit dieses Wissens zu lehren! Hätte man uns auch nur die Ehrfurcht vor diesen Wissenschaften gelehrt, hätte man uns mit dem Ringen und Unterliegen und Wieder-Weiterkämpfen der Großen, von dem Martyrium, welches die Geschichte der strengen Wissenschaft ist, auch nur Ein Mal die Seele erzittern machen!

- Something that can no longer be made good: the squandering of our youth when our educators failed to employ those eager, hot and thirsty years to lead us toward knowledge of things, but used them for a so-called ‘classical education’! The squandering of our youth when we had a meager knowledge of the Greeks and Romans and their languages drummed into us in a way as clumsy as it was painful and one contrary to the supreme principle of all education, that one should offer food only to him who hungers for it! When we had mathematics and physics forced upon us instead of our being led into despair at our ignorance and having our little daily life, our activities, and all that went on at home, in the workplace, in the sky, in the countryside from morn to night, reduced to thousands of problems, to annoying, mortifying, irritating problems—so as to show us that we needed a knowledge of mathematics and mechanics, and then to teach us our first delight in science through showing us the absolute consistency of this knowledge! If only we had been taught to revere these sciences, if only our souls had even once been made to tremble at the way in which the great men of the past had struggled and been defeated and had struggled anew, at the martyrdom which constitutes the history of rigorous science!

- R. Hollingdale, trans. (Cambridge: 1997), § 195

- Something that can no longer be made good: the squandering of our youth when our educators failed to employ those eager, hot and thirsty years to lead us toward knowledge of things, but used them for a so-called ‘classical education’! The squandering of our youth when we had a meager knowledge of the Greeks and Romans and their languages drummed into us in a way as clumsy as it was painful and one contrary to the supreme principle of all education, that one should offer food only to him who hungers for it! When we had mathematics and physics forced upon us instead of our being led into despair at our ignorance and having our little daily life, our activities, and all that went on at home, in the workplace, in the sky, in the countryside from morn to night, reduced to thousands of problems, to annoying, mortifying, irritating problems—so as to show us that we needed a knowledge of mathematics and mechanics, and then to teach us our first delight in science through showing us the absolute consistency of this knowledge! If only we had been taught to revere these sciences, if only our souls had even once been made to tremble at the way in which the great men of the past had struggled and been defeated and had struggled anew, at the martyrdom which constitutes the history of rigorous science!

- The surest way to corrupt a youth is to instruct him to hold in higher esteem those who think alike than those who think differently.

- § 297

- It is not enough to prove something, one has also to seduce or elevate people to it. That is why the man of knowledge should learn how to speak his wisdom: and often in such a way that it sounds like folly!

- § 330

- Wehe dem Denker, der nicht der Gärtner, sondern nur der Boden seiner Gewächse ist!

- Woe to the thinker who is not the gardener but only the soil of the plants that grow in him.

- § 382